Does the Death Penalty Require Death Row? the Harm of Legislative Silence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuba and the World.Book

CUBA FUTURES: CUBA AND THE WORLD Edited by M. Font Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies Presented at the international symposium “Cuba Futures: Past and Present,” organized by the The Cuba Project Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies The Graduate Center/CUNY, March 31–April 2, 2011 CUBA FUTURES: CUBA AND THE WORLD Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies www.cubasymposium.org www.bildner.org Table of Contents Preface v Cuba: Definiendo estrategias de política exterior en un mundo cambiante (2001- 2011) Carlos Alzugaray Treto 1 Opening the Door to Cuba by Reinventing Guantánamo: Creating a Cuba-US Bio- fuel Production Capability in Guantánamo J.R. Paron and Maria Aristigueta 47 Habana-Miami: puentes sobre aguas turbulentas Alfredo Prieto 93 From Dreaming in Havana to Gambling in Las Vegas: The Evolution of Cuban Diasporic Culture Eliana Rivero 123 Remembering the Cuban Revolution: North Americans in Cuba in the 1960s David Strug 161 Cuba's Export of Revolution: Guerilla Uprisings and Their Detractors Jonathan C. Brown 177 Preface The dynamics of contemporary Cuba—the politics, culture, economy, and the people—were the focus of the three-day international symposium, Cuba Futures: Past and Present (organized by the Bildner Center at The Graduate Center, CUNY). As one of the largest and most dynamic conferences on Cuba to date, the Cuba Futures symposium drew the attention of specialists from all parts of the world. Nearly 600 individuals attended the 57 panels and plenary sessions over the course of three days. Over 240 panelists from the US, Cuba, Britain, Spain, Germany, France, Canada, and other countries combined perspectives from various fields including social sciences, economics, arts and humanities. -

AS/Jur (2019) 50 11 December 2019 Ajdoc50 2019

Declassified AS/Jur (2019) 50 11 December 2019 ajdoc50 2019 Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights Abolition of the death penalty in Council of Europe member and observer states,1 Belarus and countries whose parliaments have co-operation status2 – situation report Revised information note General rapporteur: Mr Titus CORLĂŢEAN, Romania, Socialists, Democrats and Greens Group 1. Introduction 1. Having been appointed general rapporteur on the abolition of the death penalty at the Committee meeting of 13 December 2018, I have had the honour to continue the outstanding work done by Mr Yves Cruchten (Luxemburg, SOC), Ms Meritxell Mateu Pi (Andorra, ALDE), Ms Marietta Karamanli (France, SOC), Ms Marina Schuster (Germany, ALDE), and, before her, Ms Renate Wohlwend (Liechtenstein, EPP/CD).3 2. This document updates the previous information note with regard to the development of the situation since October 2018, which was considered at the Committee meeting in Strasbourg on 10 October 2018. 3. This note will first of all provide a brief overview of the international and European legal framework, and then highlight the current situation in states that have abolished the death penalty only for ordinary crimes, those that provide for the death penalty in their legislation but do not implement it and those that actually do apply it. It refers solely to Council of Europe member states (the Russian Federation), observer states (United States, Japan and Israel), states whose parliaments hold “partner for democracy” status, Kazakhstan4 and Belarus, a country which would like to have closer links with the Council of Europe. Since March 2012, the Parliamentary Assembly’s general rapporteurs have issued public statements relating to executions and death sentences in these states or have proposed that the Committee adopt statements condemning capital punishment as inhuman and degrading. -

VADP 2015 Annual Report Accomplishments in 2015

2015 Annual Report Working to End the Death Penalty through Education, Organizing and Advocacy for 24 years VADP Executive Directors, Past and Present From left: Beth Panilaitis (2008 -2010), Steve Northup (2011 -2014), Jack Payden -Travers (2002 -2007), and Michael Stone (2015). Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty P.O. Box 12222 Richmond, VA 23241 (434) 960 -7779 [email protected] www.vadp.org Message from the VADP Board President Dear VADP Supporter, resources to band together the various groups and Last year was a time of strong forward movement individuals who oppose the death penalty, for VADP. In January, we hired Michael Stone, whatever their reasons, into a cohesive force. our first full time executive director in four years, I would like to thank those of you who made a and that led to the implementation of bold new monetary donation to VADP in 2015. But our strategies and expanded programs. work is not done. So I ask you to increase your In 2015 we learned what can be accomplished in support in 2016 and to help us find others to join today’s politics when groups with different overall this important movement. And, if you are not yet purposes decide to work together on a specific a supporter of VADP, now is the time to join our shared objective — such as vital work to end the death penalty in Virginia, death penalty abolition. That, once and for all. happily, is starting to occur. Sincerely, As an example, nationally and Kent Willis in Virginia activists from every Board President point on the political spectrum are joining an extraordinary new movement to re -examine The Death Penalty in Virginia how we waste tax dollars on our expensive and ineffective criminal justice system, including ♦ Virginia has executed 111 men and women capital punishment. -

Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission

The Report of the The Report Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission Review Penalty Oklahoma Death The Report of the Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission OKDeathPenaltyReview.org The Report of the Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission The Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission is an initiative of The Constitution Project®, which sponsors independent, bipartisan committees to address a variety of important constitutional issues and to produce consensus reports and recommendations. The views and conclusions expressed in these reports, statements, and other material do not necessarily reflect the views of members of its Board of Directors or its staff. For information about this report, or any other work of The Constitution Project, please visit our website at www. constitutionproject.org or e-mail us at [email protected]. Copyright © March 2017 by The Constitution Project ®. All rights reserved. No part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of The Constitution Project. Book design by Keane Design & Communications, Inc/keanedesign.com. Table of Contents Letter from the Co-Chairs .........................................................................................................................................i The Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission ..............................................................................iii Executive Summary................................................................................................................................................. -

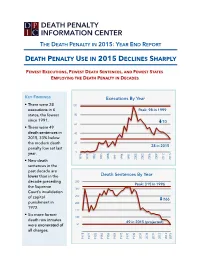

Year End Report

THE DEATH PENALTY IN 2015: YEAR END REPORT DEATH PENALTY USE IN 2015 DECLINES SHARPLY FEWEST EXECUTIONS, FEWEST DEATH SENTENCES, AND FEWEST STATES EMPLOYING THE DEATH PENALTY IN DECADES KEY FINDINGS Executions By Year • There were 28 100 executions in 6 Peak: 98 in 1999 states, the fewest 80 since 1991. ⬇70 60 • There were 49 death sentences in 40 2015, 33% below the modern death 20 28 in 2015 penalty low set last year. 0 • New death 1976 1979 1982 1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015 sentences in the past decade are lower than in the Death Sentences By Year decade preceding 350 Peak: 315 in 1996 the Supreme 300 Court’s invalidation of capital 250 ⬇266 punishment in 200 1972. 150 • Six more former 100 death row inmates 49 in 2015 (projected) were exonerated of 50 all charges. 1974 1977 1980 1983 1986 1989 1992 1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2015 THE DEATH PENALTY IN 2015: YEAR END REPORT U.S. DEATH PENALTY DECLINE ACCELERATES IN 2015 By all measures, use of and support for the death penalty Executions by continued its steady decline in the United States in 2015. The 2015 2014 State number of new death sentences imposed in the U.S. fell sharply from already historic lows, executions dropped to Texas 13 10 their lowest levels in 24 years, and public opinion polls revealed that a majority of Americans preferred life without Missouri 6 10 parole to the death penalty. Opposition to capital punishment polled higher than any time since 1972. -

Food in Prison: an Eighth Amendment Violation Or Permissible Punishment?

University of South Dakota USD RED Honors Thesis Theses, Dissertations, and Student Projects Spring 2020 Food In Prison: An Eighth Amendment Violation or Permissible Punishment? Natasha M. Clark University of South Dakota Follow this and additional works at: https://red.library.usd.edu/honors-thesis Part of the Courts Commons, Food and Drug Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Natasha M., "Food In Prison: An Eighth Amendment Violation or Permissible Punishment?" (2020). Honors Thesis. 109. https://red.library.usd.edu/honors-thesis/109 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Student Projects at USD RED. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Thesis by an authorized administrator of USD RED. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOOD IN PRISON: AN EIGHTH AMENDMENT VIOLATION OR PERMISSIBLE PUNISHMENT? By Natasha Clark A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the University Honors Program Department of Criminal Justice The University of South Dakota Graduation May 2020 The members of the Honors Thesis Committee appointed to examine the thesis of Natasha Clark find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. Professor Sandy McKeown Associate Professor of Criminal Justice Director of the Committee Professor Thomas Horton Professor & Heidepriem Trial Advocacy Fellow Dr. Thomas Mrozla Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice ii ABSTRACT FOOD IN PRISON: AN EIGHTH AMENDMENT VIOLATION OR PERMISSIBLE PUNISHMENT? Natasha Clark Director: Prof. Sandy McKeown, Associate Professor of Criminal Justice This piece analyzes aspects such as; Eighth Amendment provisions, penology, case law, privatization and monopoly, and food law, that play into the constitutionality of privatized prisons using food as punishment. -

An Economic Critique

ISSUE 22:2 FALL 2017 Why Prison?: An Economic Critique Peter N. Salib* This Article argues that we should not imprison people who commit crimes. This is true despite the fact that essentially all legal scholars, attorneys, judges, and laypeople see prison as the sine qua non of a criminal justice system. Without prison, most would argue, we could not punish past crimes, deter future crimes, or keep dangerous criminals safely separate from the rest of society. Scholars of law and economics have generally held the same view, treating prison as an indispensable tool for minimizing social harm. But the prevailing view is wrong. Employing the tools of economic analysis, this Article demonstrates that prison imposes enormous but well-hidden societal losses. It is therefore a deeply inefficient device for serving the utilitarian aims of the criminal law system—namely, optimally deterring bad social actors while minimizing total social costs. The Article goes on to engage in a thought experiment, asking whether an alternative system of criminal punishment could serve those goals more efficiently. It concludes that economically superior alternatives to prison are currently available. The alternatives are practicable. They plausibly comport with our current legal rules and more general moral principles. They could theoretically be implemented tomorrow, and, if we wished, we could bid farewell forever to our sprawling, socially-suboptimal system of imprisonment. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15779/Z38M902321 Copyright © 2017 Regents of University of California * Associate, Sidley Austin LLP. Special thanks to Jonathan S. Masur and Anup Malani for their comments and critiques. SALIB FALL 2017 112 BERKELEY JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW Vol. -

FLORIDA PRISON LEGAL Ers .Ectives OLUME 14 ISSUE 2 ISSN# 1091-8094 MAR/APR 2008

FLORIDA PRISON LEGAL ers .ectives OLUME 14 ISSUE 2 ISSN# 1091-8094 MAR/APR 2008 2009 and overcrowding ifnew prisons aren't funded. T.ents Used to Scare. Lawmakers hung tough, some suggesting hanging extra Legislators Into Funding bunks in cells housing non-violent and elderly prisoners (without regard to space requirementS).' Another' More Prisons' suggestion was made to send florida prisoners to prisons in other states, which other states with overcrowding hortly after the Florida Legislature went into its problems have been doing for years. The FDOC swung Sregular session in March ofthis year, with deep cuts in back, saying it has no plans to send· prisoners out ofstate, agencies' budgets expected in the face of a state budget but it does have plans to buy metal buildings that can be shortfall, the Florida Department of'Corrections came out readied quickly for prisoners and surplus military tents to fighting for an increase to its budget to continue building houSe prisonerS. ' ' more prisons. In fact, punching quickly, by the end of March the The FDOC's first blow ' was ;a right' cross, 'the FDOC announced. that it was already putting up tents at department's secretary warned legislators that large budget eight prisons around the state. Uping the rhetoric, the cuts will lead to more cramped and dangerous -prisons and FDOC justified ~e 'tents claiming the system was getting a rise in crime around the state. "dangerously close to reaching 99 percent capacity," at In January the FDOC was riding high, Gov. Crist's which point state law will' mandate earlyrel~se for proposed state budget urged 'lawmakers to give the prison certain prisoners. -

Death Row U.S.A

DEATH ROW U.S.A. Fall 2020 A quarterly report by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Deborah Fins Consultant to the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Death Row U.S.A. Fall 2020 (As of October 1, 2020) TOTAL NUMBER OF DEATH ROW INMATES KNOWN TO LDF: 2553 (2553 – 180* - 877M = 1496 enforceable sentences) Race of Defendant: White 1,076 (42.15%) Black 1,062 (41.60%) Latino/Latina 343 (13.44%) Native American 24 (0.94%) Asian 47 (1.84%) Unknown at this issue 1 (0.04%) Gender: Male 2,502 (98.00%) Female 51 (2.00%) JURISDICTIONS WITH CURRENT DEATH PENALTY STATUTES: 30 Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, CaliforniaM, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, OregonM, PennsylvaniaM, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Wyoming, U.S. Government, U.S. Military. M States where a moratorium prohibiting execution has been imposed by the Governor. JURISDICTIONS WITHOUT DEATH PENALTY STATUTES: 23 Alaska, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire [see note below], New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin. [NOTE: New Hampshire repealed the death penalty prospectively. The man already sentenced remains under sentence of death.] * Designates the number of people in non-moratorium states who are not under active death sentence because of court reversal but whose sentence may be reimposed. M Designates the number of people in states where a gubernatorial moratorium on execution has been imposed. -

Who's Looking?

INTRO PART 1 PART 2 PART 3 PART 4 PART 5 PART 6 PART 5 Who’s Looking? Who’s Listening? “One day every three months it would be good; [the trays] would be full because they had a kitchen inspection.” — formerly incarcerated person This section examines the meager systems of accountability that have often failed to ensure food safety and quality, allowing the violations of health and dignity we’ve detailed in the earlier installments of Eating Behind Bars. In the world beyond the prison gate, commercial and other large-scale kitchens are subject to rigorous health inspections. Inspectors show up without advance notice, are not shy to document violations, and can force kitchens to close until the problems are remedied. In this way, health departments protect the dining public. Kitchens in prisons are not subject to anywhere near the same degree of independent external oversight. PART 5 | WHO’S LOOKING? WHO’S LISTENING? 2 A quick clean-up Prisons that are subject to health department inspections—and in some states they aren’t—typically know ahead of time when an inspection will take place. The same is true of an audit by the American Correctional Association and internal reviews by the correctional agency itself. As Theo told us, “When they do come in, the kitchen is spotless, the correct portion sizes are served. One day every three months it would be good, [the trays] would be full because they had a kitchen inspection.” Our surveys and interviews suggest that a quick clean-up to present a sanitary kitchen and safe food handling is routine in both public and private correctional facilities. -

January 6, 2012

January 6, 2012 Friday, September 9, 2011 in conjunction with Marion County Superior Court Probation Department, Marion County Community Corrections, and Marion County Sheriff’s Department -Sex and ViolentMiami Offender Correctional Unit, Facility’s American Legion Post 555 held a dedication ceremony for a flag pole it purchased and installed inside the fence of the facility. The legion members will be raising and lowering the flag each day at 8 a.m. and 4:30 p.m., which is the same time the nearby Grissom Air Reserve Base plays reveille and taps on their speaker system. (see photo below) Miami Correctional Facility’s PLUS Unit donated $200 to the Special Olympics through Captain Doug Nelson, who will be participating in the local Polar Bear Plunge on February 11th. The plunge is an annual event to raise money for Special Olympics. This year the plunge will be at the Crossroads Community Church in Kokomo, IN. Those participating take a plunge in frigid waters during what is hoped to be the coldest day of the year. A reception was held at the Indianapolis Re-Entry Educational Facility (IREF) for Dennis Ludwick, who retired after 24 years of dedicated service to the Indiana Department of Correction (IDOC). Mr. Ludwick began his career with the IDOC on December 21, 1987 as a correctional officer at the Plainfield Correctional Facility. Throughout his 24-year career, Mr. Ludwick promoted to several positions within IDOC, including Correctional Counselor, Psychiatric Social Services Specialist III, Instructor of the Effective Fathering and Substance Abuse Programs, Social Security Representative, Veteran Administrative Representative, and Community Involvement Coordinator. -

The Death of Punishment: Searching for Justice Among the Worst of the Worst

The Death of Punishment: Searching for Justice Among the Worst of the Worst By Robert Blecker, Palgrave MacMillan, N.Y., 314 pages, $28 hardcover. Jeffrey Kirchmeier , New York Law Journal May 12, 2014 When Oklahoma recently botched the lethal injection of a condemned man, death penalty opponents decried the execution as inhumane. While many death penalty advocates also criticized the procedural mistakes, some people argued that the man's horrible crime justified his agony. Throughout history, humans have debated how much suffering governments should inflict on criminals, and in his new book, "The Death of Punishment: Searching for Justice Among the Worst of the Worst," New York Law School Professor Robert Blecker explores the role of retribution in the criminal justice system. While arguing that our system should be more grounded in retributive theories, he concludes that the United States both under-punishes some crimes and over-punishes others. In "The Death of Punishment," Blecker critiques a system that focuses on housing criminals as a way of punishing and preventing crime. He reasons that society gives too little weight to retributive goals of sentencing, arguing that our anger at horrible crimes justifies more severe punishments. As an advocate for the death penalty, he asserts that egregious murderers should suffer a painful, but quick, death. He prefers the firing squad to lethal injection because the former looks like punishment, not a medical procedure. Further, he complains that prisons house people in too much comfort when prisons should be punitive institutions of suffering where inmates are constantly reminded of their victims in an unpleasant environment with tasteless food.