Iran's War on Protesters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read the Annual Report on the Death Penalty in Iran

ANNUAL REPORT ON THE DEATH PENALTY IN IRAN 2020 In 2020, the year of the extraordinary and overwhelming worldwide COVID-19 pandemic, most countries have been fighting to save lives. Meanwhile, Iran not only continued executing as usual, ANNUAL REPORT but used the death penalty more than ever to nip the freedom of speech and expression in the bud. The death penalty in 2020 has been used as a repressive tool against protesters, ethnic minority groups and any opponents or independent thinkers. Nevertheless, this report shows how exasperated the Iranian population is with the authorities’ ON THE DEATH PENALTY practices. Public opposition to the death penalty has increased drastically. Mass online campaigns of millions of Iranians expressing their opposition to the death penalty and the dramatic increase in the number of people choosing diya (blood money) or forgiveness over execution, are all examples of this opposition. With this report, we demand transparency and accountability and IN IRAN 2020 call on the international community to support the abolitionist movement in Iran. 2020 ON THE DEATH PENALTY IN IRAN ANNUAL REPORT © IHR, ECPM, 2021 ISBN : 978-2-491354-18-3 Mahmood Amiry-Moghaddam Director Iran Human Rights (IHR) and ECPM Iran Human Rights Raphaël Chenuil-Hazan have been working together since P.O.Box 2691 Solli Executive director 2011 for the international release and circulation of the annual report 0204 Oslo - Norway Email: [email protected] on the death penalty in Iran. IHR Tel: +47 91742177 62bis avenue Parmentier and ECPM see the death penalty as Email: [email protected] 75011 PARIS a benchmark for the human rights situation in the Islamic Republic of Iran. -

Iran's American and Other Western Hostages

Iran’s American and Other Western Hostages August 2021 11 Table of Contents Background ................................................................................................................................................... 4 American Hostages ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Baquer Namazi ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Emad Shargi .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Karan Vafadari and Afarin Niasari ..................................................................................................... 10 Morad Tahbaz ..................................................................................................................................... 13 Siamak Namazi ................................................................................................................................... 16 Other Western Hostages ............................................................................................................................ 18 Abdolrasoul Dorri-Esfahani ................................................................................................................ 18 Ahmadreza Djalali ............................................................................................................................. -

Human Rights Violations Under Iran's National Security Laws – June 2020

In the Name of Security Human rights violations under Iran’s national security laws Drewery Dyke © Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights and Minority Rights Group International June 2020 Cover photo: Military parade in Tehran, September 2008, to commemorate anniversary of This report has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. Iran-Iraq war. The event coincided The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the publishers and can under with escalating US-Iran tensions. no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. © Behrouz Mehri/AFP via Getty Images This report was edited by Robert Bain and copy-edited by Sophie Richmond. Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights The Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights is a new initiative to develop ‘civilian-led monitoring’ of violations of international humanitarian law or human rights, to pursue legal and political accountability for those responsible for such violations, and to develop the practice of civilian rights. The Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights is registered as a charity and a company limited by guarantee under English law; charity no: 1160083, company no: 9069133. Minority Rights Group International MRG is an NGO working to secure the rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and indigenous peoples worldwide, and to promote cooperation and understanding between communities. MRG works with over 150 partner organizations in nearly 50 countries. It has consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and observer status with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR). MRG is registered as a charity and a company limited by guarantee under English law; charity no: 282305, company no: 1544957. -

Cruel and Inhuman: Executions and Other Barbarities in Iran's Judicial

Cruel and Inhuman: Executions and Other Barbarities in Iran’s Judicial System April 2021 Table of Contents Preface .................................................................................................................................. 3 Executions ............................................................................................................................. 4 Executions in Iran by the Numbers .................................................................................................4 Targets for Execution .....................................................................................................................4 Executions in Iran 2005–2019* .......................................................................................................5 Methods of Execution ....................................................................................................................5 Execution of Navid Afkari ...............................................................................................................5 Execution of Ruhollah Zam .............................................................................................................6 Recent Executions of Ethnic Minorities ...........................................................................................7 Other Evils in Iran’s Judicial System ........................................................................................ 8 Severe Forms of Punishment besides Execution ..............................................................................8 -

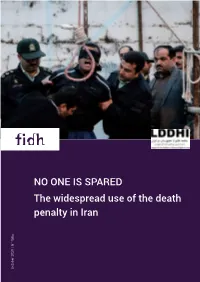

NO ONE IS SPARED the Widespread Use of the Death Penalty in Iran

NO ONE IS SPARED The widespread use of the death penalty in Iran October 2020 / N° 758a October Cover picture : Balal, who killed Iranian youth Abdolah Hosseinzadeh in a street fight with a knife in 2007, is brought to the gallows during his execution ceremony in Noor, Mazandaran Province, on 15 April 2014. The mother of Abdolah Hosseinzadeh spared the life of her son’s convicted murderer, with an emotional slap in the face as he awaited execution prior to removing the noose around his neck. © ARASH KHAMOOSHI / ISNA / AFP Table of Contents Executive summary ...............................................................................................................................4 Acronyms ...............................................................................................................................................7 Methodology ..........................................................................................................................................8 The world’s second top executioner .....................................................................................................9 Barbaric methods of execution ........................................................................................................................... 9 Capital crimes inconsistent with international law ..............................................................................11 Sex-related offenses .............................................................................................................................................. -

Situation of Human Rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Report

United Nations A/HRC/43/61 General Assembly Distr.: General 28 January 2020 Original: English Human Rights Council Forty-third session 24 February–20 March 2020 Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran* Summary The present report, submitted pursuant to General Assembly resolution 74/167, provides an overview of human rights concerns in the Islamic Republic of Iran, including the use of the death penalty, the execution of child offenders, the rights to freedom of opinion, expression, association and assembly, the human rights situation of women and girls, the human rights situation of minorities and the impact of sanctions. The report also provides an overview of the legal framework governing detention and an assessment of the human rights concerns arising from conditions in prisons and detention centres in the Islamic Republic of Iran in light of the country’s human rights obligations under international law. * Agreement was reached to publish the present report after the standard publication date owing to circumstances beyond the submitter’s control. GE.20-01246(E) A/HRC/43/61 I. Introduction 1. The present report, submitted pursuant to General Assembly resolution 74/167, is divided into two parts. The first part describes pressing human rights concerns in the Islamic Republic of Iran. The second part examines human rights concerns related to conditions of detention in the country. 2. In 2019, the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran met with victims of alleged violations, their families, human rights defenders, lawyers and representatives of civil society organizations, including in the Netherlands and Austria (2–8 June 2019) and in the United States of America (4–8 November 2019). -

Iran 2020 Human Rights Report

IRAN 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Islamic Republic of Iran is an authoritarian theocratic republic with a Shia Islamic political system based on velayat-e faqih (guardianship of the jurist). Shia clergy, most notably the rahbar (supreme leader), and political leaders vetted by the clergy dominate key power structures. The supreme leader is the head of state. The members of the Assembly of Experts are nominally directly elected in popular elections. The assembly selects and may dismiss the supreme leader. The candidates for the Assembly of Experts, however, are vetted by the Guardian Council (see below) and are therefore selected indirectly by the supreme leader himself. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has held the position since 1989. He has direct or indirect control over the legislative and executive branches of government through unelected councils under his authority. The supreme leader holds constitutional authority over the judiciary, government-run media, and other key institutions. While mechanisms for popular election exist for the president, who is head of government, and for the Islamic Consultative Assembly (parliament or majles), the unelected Guardian Council vets candidates, routinely disqualifying them based on political or other considerations, and controls the election process. The supreme leader appoints half of the 12-member Guardian Council, while the head of the judiciary (who is appointed by the supreme leader) appoints the other half. Presidential elections held in 2017 and parliamentary elections held during the year were not considered free and fair. The supreme leader holds ultimate authority over all security agencies. Several agencies share responsibility for law enforcement and maintaining order, including the Ministry of Intelligence and Security and law enforcement forces under the Interior Ministry, which report to the president, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, which reports directly to the supreme leader. -

En En Motion for a Resolution

European Parliament 2019-2024 Plenary sitting B9-0443/2020 15.12.2020 MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION with request for inclusion in the agenda for a debate on cases of breaches of human rights, democracy and the rule of law pursuant to Rule 144 of the Rules of Procedure on Iran, in particular the case of 2012 Sakharov Prize laureate Nasrin Sotoudeh (2020/2914(RSP)) Hilde Vautmans, Petras Auštrevičius, Malik Azmani, Izaskun Bilbao Barandica, Dita Charanzová, Olivier Chastel, Klemen Grošelj, Bernard Guetta, Svenja Hahn, Karin Karlsbro, Ilhan Kyuchyuk, Javier Nart, Frédérique Ries, María Soraya Rodríguez Ramos, Nicolae Ştefănuță, Ramona Strugariu, Marie-Pierre Vedrenne on behalf of the Renew Group RE\P9_B(2020)0443_EN.docx PE662.799v01-00 EN United in diversityEN B9-0443/2020 European Parliament resolution on Iran, in particular the case of 2012 Sakharov Prize laureate Nasrin Sotoudeh (2020/2914(RSP)) The European Parliament, - having regard to its resolution of 13 December 2018 on Iran, notably the case of Nasrin Sotoudeh; as well as its previous resolutions including its most recent of December 18 2019 on the violent crackdown on the recent protests in Iran; of 19 September 2019 on Iran, notably the situation of women’s rights defenders and imprisoned EU dual nationals and of 14 March 2019 on Iran, notably the case of human rights defenders, - having regard to the EU Council decision of 8 April 2019 to extend its restrictive measures for a further 12 months in response to serious human rights violations in Iran, and EU Council Conclusions of 4 -

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options Updated July 29, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32048 SUMMARY RL32048 Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and July 29, 2021 Options Kenneth Katzman U.S.-Iran relations have been mostly adversarial since the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, Specialist in Middle occasionally flaring into direct conflict while at other times witnessing negotiations or tacit Eastern Affairs cooperation on selected issues. U.S. officials have consistently identified the regime’s support for militant Middle East groups as a significant threat to U.S. interests and allies, and limiting the expansion of Iran’s nuclear program has been a key U.S. policy goal for nearly two decades. The Obama Administration engaged Iran directly and obtained a July 2015 multilateral nuclear agreement (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, JCPOA) that exchanged sanctions relief for limits on Iran’s nuclear program. The accord did not contain binding curbs on Iran’s missile program or its regional interventions, or any requirements that the Iranian government improve its human rights practices. The Trump Administration criticized the JCPOA’s perceived shortcomings and, returning to prior policies of seeking to weaken Iran strategically, on May 8, 2018, it ceased implementing U.S. commitments under the JCPOA and reimposed all U.S. sanctions. The stated intent of the Trump Administration’s “maximum pressure” policy on Iran was to compel it to change its behavior, including negotiating a new nuclear agreement that encompassed the broad range of U.S. concerns. Iran responded by exceeding nuclear limits set by the JCPOA and by attacking Saudi Arabia as well as commercial shipping in the Persian Gulf, and supporting attacks by its allies in Iraq and Yemen on U.S., Saudi, and other targets in the region. -

NO ONE IS SPARED the Widespread Use of the Death Penalty in Iran

NO ONE IS SPARED The widespread use of the death penalty in Iran October 2020 / N° 758a October Cover picture : Balal, who killed Iranian youth Abdolah Hosseinzadeh in a street fight with a knife in 2007, is brought to the gallows during his execution ceremony in Noor, Mazandaran Province, on 15 April 2014. The mother of Abdolah Hosseinzadeh spared the life of her son’s convicted murderer, with an emotional slap in the face as he awaited execution prior to removing the noose around his neck. © ARASH KHAMOOSHI / ISNA / AFP Table of Contents Executive summary ...............................................................................................................................4 Acronyms ...............................................................................................................................................7 Methodology ..........................................................................................................................................8 The world’s second top executioner .....................................................................................................9 Barbaric methods of execution ........................................................................................................................... 9 Capital crimes inconsistent with international law ..............................................................................11 Sex-related offenses .............................................................................................................................................. -

Iran's War on Journalism and Journalists

IRAN’S WAR ON JOURNALISM AND JOURNALISTS May 2020 1 The Iranian regime is one of the world’s worst persecutors of journalists and suppressors of journalism. Tehran imprisons, harasses, and surveils journalists and their families; censors reporting—both directly and by intimidating journalists into self-censoring; and prevents the dissemination of journalism by blocking access to social media and jamming satellite-television signals. Iran’s war on journalists and journalism reflects the Islamic Republic’s fear of public knowledge of—and resistance to—its systemic malfeasance, mismanagement, and repression. Rankings Iran is the seventh most censored country in the world, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). Reporters Without Borders’ (RSF) 2020 World Press Freedom Index ranks Iran 173rd out of 180 countries, down from 170th in 2019. Jailing Journalists More than 40 journalists remained imprisoned as of May 13, 2020, according to the human rights website JournalismIsNotACrime.com. Members of the press were frequently arrested after reporting on topics considered touchy by the regime, including: widespread protests; the status of the novel coronavirus in Iran and the regime’s response; the IRGC’s missile strike on a Ukrainian airline jet over Tehran; government entities such as the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), Guardian Council, and courts; corruption; women’s rights; mistreatment of minorities and detainees; labor issues; earthquake-relief activities; and other social and cultural tensions. In some cases, the authorities detained journalists without warning and would not admit to holding them in custody. Journalists in jail are subjected to torture and other human rights violations, including extended solitary confinement and denial of family visits and access to health care and legal counsel.