North Carolina and World War I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National World War I Museum 2008 Accessions to the Collections Doran L

NATIONAL WORLD WAR I MUSEUM 2008 ACCESSIONS TO THE COLLECTIONS DORAN L. CART, CURATOR JONATHAN CASEY, MUSEUM ARCHIVIST All accessions are donations unless otherwise noted. An accession is defined as something added to the permanent collections of the National World War I Museum. Each accession represents a separate “transaction” between donor (or seller) and the Museum. An accession can consist of one item or hundreds of items. Format = museum accession number + donor + brief description. For reasons of privacy, the city and state of the donor are not included here. For further information, contact [email protected] or [email protected] . ________________________________________________________________________ 2008.1 – Carl Shadd. • Machine rifle (Chauchat fusil-mitrailleur), French, M1915 CSRG (Chauchat- Sutter-Ribeyrolles and Gladiator); made at the Gladiator bicycle factory; serial number 138351; 8mm Lebel cartridge; bipod; canvas strap; flash hider (standard after January 1917); with half moon magazine; • Magazine carrier, French; wooden box with hinged lid, no straps; contains two half moon magazines; • Tool kit for the Chauchat, French; M1907; canvas and leather folding carrier; tools include: stuck case extractor, oil and kerosene cans, cleaning rod, metal screwdriver, tension spring tool, cleaning patch holder, Hotchkiss cartridge extractor; anti-aircraft firing sight. 2008.2 – Robert H. Rafferty. From the service of Cpl. John J. Rafferty, 1 Co 164th Depot Brigade: Notebook with class notes; • Christmas cards; • Photos; • Photo postcard. 2008.3 – Fred Perry. From the service of John M. Figgins USN, served aboard USS Utah : Diary; • Oversize photo of Utah ’s officers and crew on ship. 2008.4 – Leslie Ann Sutherland. From the service of 1 st Lieutenant George Vaughan Seibold, U.S. -

The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2Nd December 1917

Centre for First World War Studies A Moonlight Massacre: The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2nd December 1917 by Michael Stephen LoCicero Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This thesis, a necessary corrective to published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as „Passchendaele‟, examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. -

J. HOWARD MATHEWS Firearms Identification

• ]. Ho\\'ard Mathc\,-s lrearms • • entl catIon YOL' ". III O,~lph>togr.""".nd_IIIwm...",.,lt.ouJ g''"'" l)oj. "" nll,,~ dwaru-,io'>n of ""nod " ....... 1 ..... ~d ro.rhu.oo" ... r~ ,J" [J,j..wl ,\,,;_ ..; Au.~ [. \\'.,,,,,~-. ........... , M"",~ Sp<ri</i>t. '1"_ 'NJ""'''''''''''' "'-""" (.'~ ... 1.. I><A.trOOJ s.""", .Il.. ~_. WI>;;o,"'fi The "real work" o f this posthumously published third volume was all done by Dr. J. H. Mathews. AU that was necessary at the time of his death was to mount the photographs and complete the editorial work of pulling the book together for publication. The third volume contains additional data for many makes and models for which data on other specimens were given in Volume I. Also, much previously unavailable data on rifles is presented along with data for many handguns not before encountered . Photographs of many previously unphotographed handguns have been included as well as photographs of guns in partially disassembled condition giving a better view of their constructi on and operation. In PART I of Volume Ill , tables are prese nted on rifling characteristics of automatic pistols, revolvers and nonautomatic pistols and rifles. As an aid to identification, material has been organized into tables, arranged by caliber, number of grooves and directi on of twist. Since, as the author pointed out, the firearms examiner may often be concerned with arms of older vintage , there is an extensive discussion in PART II of less well known American made hand guns fr om the peri od 1850 to 19 10. In Section 1 o f PART III are found original pho tographs of automatic pistols, arranged by caliber. -

International Military Cartridge Rifles and Bayonets

INTERNATIONAL MILITARY CARTRIDGE RIFLES AND BAYONETS The following table lists the most common international military rifles, their chambering, along with the most common bayonet types used with each. This list is not exhaustive, but is intended as a quick reference that covers the types most commonly encountered by today’s collectors. A Note Regarding Nomenclature: The blade configuration is listed, in parentheses, following the type. There is no precise dividing line between what blade length constitutes a knife bayonet vs. a sword bayonet. Blades 10-inches or shorter are typically considered knife bayonets. Blades over 12-inches are typically considered sword bayonets. Within the 10-12 inch range, terms are not consistently applied. For purposes of this chart, I have designated any blade over 12 inches as a sword bayonet. Country Rifle Cartridge Bayonet (type) Argentina M1879 Remington 11.15 x 58R Spanish M1879 (sword) Rolling-Block M1888 Commission 8 x 57 mm. M1871 (sword) Rifle M1871/84 (knife) M1891 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. M1891 (sword) M1891 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. None Cavalry Carbine M1891 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. M1891/22 (knife) Engineer Carbine [modified M1879] M1891/22 (knife) [new made] M1909 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. M1909 First Pattern (sword) M1909 Second Pattern (sword) M1909/47 (sword) M1909 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. M1909 Second Cavalry Carbine Pattern (sword) M1909/47 (sword) FN Model 1949 7.65 x 53 mm. FN Model 1949 (knife) FN-FAL 7.62 mm. NATO FAL Type A (knife) FAL Type C (socket) © Ralph E. Cobb 2007 all rights reserved Rev. -

Bob Was a Shoo-Shoo

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Bob Was a Shoo-Shoo Every boy that grew up in New Orleans (at least in my age group) that managed to get himself into the least bit of mischief knows that the local expression for a firecracker that doesn’t go off is a “shoo-shoo”. It means a dud, something that may have started off hot, but ended in a fizzle. It just didn’t live up to its expectations. It could also be used to describe other things that didn’t deliver the desired wallop, such as an over-promoted “hot date” or even a tropical storm that (fortunately) wasn’t as damaging as its forecast. Back in 1968, I thought for a moment that I was that “dud” date, but was informed by the young lady I was escorting that she had called me something entirely different. “Chou chou” (pronounced exactly like shoo-shoo) was a reduplicative French term of endearment, meaning “my little cabbage”. Being a “petite” healthy leafy vegetable was somehow a lot better than being a non-performing firecracker. At least I wasn’t the only one. In 2009 the Daily Mail reported on a “hugely embarrassing video” in which Carla Bruni called Nicolas Sarkozy my ‘chou chou’ and “caused a sensation across France”. Bruni and Sarkozy: no “shoo-shoo” here The glamourous former model turned pop singer planted a passionate kiss on the French President and then whispered “‘Bon courage, chou chou’, which means ‘Be brave, my little darling’.” The paper explained, “A ‘chou’ is a cabbage in French, though when used twice in a row becomes a term of affection between young lovers meaning ‘little darling’.” I even noticed in the recent French movie “Populaire” that the male lead called his rapid-typing secretary and love interest “chou”, which somehow became “pumpkin” in the subtitles. -

To Examine the Horrors of Trench Warfare

TRENCH WARFARE Objective: To examine the horrors of trench warfare. What problems faced attacking troops? What was Trench Warfare? Trench Warfare was a type of fighting during World War I in which both sides dug trenches that were protected by mines and barbed wire Cross-section of a front-line trench How extensive were the trenches? An aerial photograph of the opposing trenches and no-man's land in Artois, France, July 22, 1917. German trenches are at the right and bottom, British trenches are at the top left. The vertical line to the left of centre indicates the course of a pre-war road. What was life like in the trenches? British trench, France, July 1916 (during the Battle of the Somme) What was life like in the trenches? French soldiers firing over their own dead What were trench rats? Many men killed in the trenches were buried almost where they fell. These corpses, as well as the food scraps that littered the trenches, attracted rats. Quotes from soldiers fighting in the trenches: "The rats were huge. They were so big they would eat a wounded man if he couldn't defend himself." "I saw some rats running from under the dead men's greatcoats, enormous rats, fat with human flesh. My heart pounded as we edged towards one of the bodies. His helmet had rolled off. The man displayed a grimacing face, stripped of flesh; the skull bare, the eyes devoured and from the yawning mouth leapt a rat." What other problems did soldiers face in the trenches? Officers walking through a flooded communication trench. -

Lot Description Bid a 1 Small Arms of the Anglo-Boer War R 600.00 a 2

Classic Arms (Pty) Ltd AUCTION 65 ACCEPTED BIDS 03-Aug-19 CATEGORY A ~ COLLECTABLES Lot # Lot Description Bid A 1 Small Arms of the Anglo-Boer War R 600.00 A 2 Artillery of the Anglo Boer War R 650.00 A 3 In Unknown Africa R 1600.00 A 4 Hayes Handgun Omnibus R 450.00 A 5 Antique Detachable Colt Shoulder Stock R 1950.00 A 7 Armourer's Cutaway R4 Rifle R 12000.00 A 8 .303 Armourer's Skeleton Rifle R 1600.00 A 9 Deactivated Sanna 77 Display R 2500.00 A 10 Moisin Nagant Deactivated Rifle R 2300.00 A 11 Deactivated 7,62mm FN/R1 Rifle R 9000.00 A 12 Deactivated .303 No.4 Lee Enfield Rifle R 3500.00 A 14 .303 Deactivated Cadet Rifle R 1300.00 A 15 Tommy Helmet R 550.00 A 16 Bren Gun Tripod R 2750.00 A 17 Holsters x 3 R 500.00 A 18 16x 40 Zeiss Jena binoculars in leather case. R 1850.00 A 19 6 x Assorted Vintage Powder Flasks R 3000.00 A 20 7.62mm FN Magazines 30rd x 6 R 2750.00 A 21 7.62mm FN Magazines 20rd x 6 R 2000.00 A 22 7.62mm G3 Magazines 20rd New x 6 R 1500.00 A 23 5.56mm R4/LM4 Magazines 35rd x 6 R 2500.00 A 24 7.62x39mm AK Magazines x 6 R 1500.00 A 25 9mmp Uzi Magazines x 6 R 1300.00 A 26 7.62x54r DP LMG Magazines x 6 R 2500.00 A 27 9mmp FN-HP 32rd & 25r. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

Us M31 Rifle Grenade

1 DOUBLE STACK Manufactured NOW'S THE TIME!! ITALIAN JUST by Israel, these PISTOL MAG LOADER parts sets were BE THE FIRST GOTHIC IN!! stripped down TO KNOW ABOUT FOR 9MM & 40 S&W from Israeli OUR DEALS !!! Rugged synthetic Military Service ARMOR Join Our EMAIL BLAST List loader with an rifles and are in JUST Beautifully con- Today By Texting SARCO to ergonomic feel is very good shape structed Medieval 22828 And Receive A SPE- comfortable to use IN!! and contain all set of Italian Gothic CIAL DISCOUNT ! By doing so, and saves your parts for the Armor in steel that you’ll get our latest email blast finger tips and gun except for patience! The comes with Sword, offers, sale items and notifi- the barrel and cations of new goodies com- Loader is perfect Wood Base, and Ar- receiver. The set for the double ing in! AND… after you sign mature to hold the comes with a stack magazines up, receive a FREE deck of set in place. Overall Sling and Metric that load with 9mm authentic Cold War, Unissued & & 40 S&W ammo. height on stand is 20 rd. magazine Illustrated AIRCRAFT CARDS! Black color, New over 6.5 feet high. where permitted by law. Perfect kit for building your shooting FAL with one of the semi Just add them to your cart List price is $12.95 Extremely auto receivers and barrels offered elsewhere. Kit is sold without flash hider. using part number MISC168 SARCO SPECIAL limited ............................................................................................................... $425.00 FAL320 and enter source code EMAIL- ............... $7.95 each .........$1,200.00 Add a flash hider for an extra .............................................................................. -

NJS: an Interdisciplinary Journal Summer 2017 27

NJS: An Interdisciplinary Journal Summer 2017 27 NJS Presents A Special Feature New Jersey and the Great War: Part I By Dr. Richard J. Connors DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14713/njs.v3i2.83 As April 2017 marked the 100th anniversary of America’s entry into World War I, this edition of NJS has several related offerings. These include this special feature, an adapted version of the first half of Dr. Richard J. Connors’ new book, New Jersey and the Great War (Dorrance, 2017). We will publish the second half in our Winter 2018 issue. Those who can’t wait, or who want to see the unedited text (to include endnotes, illustrations, and tables) can always purchase the book online! We are most grateful to Dr. Connors for allowing us to share his insightful and comprehensive work in this way, and hope you will help us ensure the widest possible dissemination by sharing the very timely piece with your colleagues, students, family, and friends. Preface When my generation were youngsters, “the war” was the Great War, now known as World War I. On Memorial Day we bought artificial flowers in remembrance of the veterans lying in European cemeteries “where poppies grow between the crosses, row on row.” On Armistice Day, November 11, we went to our local cemeteries to honor departed neighbors, especially those whose bodies were re-interred from France. At the movies, rarely air-conditioned, for a ten cent admission we watched Lew Ayres in All Quiet on the Western Front, or Errol Flynn in Dawn Patrol, plus the latest Buck Rogers serial. -

CONGR.ESSION AL RECORD-HOUSE. }Lay 31, Bill 2104 Th::Tt We Had up a Few Days Ago, the Purpose of Which 1\Ir

.7234 CONGR.ESSION AL RECORD-HOUSE. }lAY 31, bill 2104 th::tt we had up a few days ago, the purpose of which 1\Ir. 1\IADDEN. Then let us amenu it so that it will say so. i to increa e the salaries of the boiler inspectors. If there is 1\fr. GARRET'".r of Tennessee. For the time being I make a not to be any oppo ition to that bill, it bus been on the calendar point of order on the re olution. for many months, and the department is very much desirous Mr. MADDEN. I do not think the point of order is well taken· to have the legislation enacted. I think the resolution simply asks for facts. It does not ask fo~ 1\Ir. SMOOT. I will say to the Senator from Mississippi that an opinion. It a ks for information which ought to be in I received in thi morning's mail a number of communications pos e sion of the department to which the re olution i ad upon the que tion of steamboat inspectors. I have not yet had dresseti. time to reati them, anti I want the bill to go over at least until The SPE..i.KER. What does the gentleman say about this I can exnmiue the letters which I have already received. language: l\Ir. V .A.RDAMAN. I am not going to urge the consideration That the Interstate Commerce Commi sion be requested to report to of the measure at this time, but it is very necessary that it shall the House the number of men in the s ervice of the commission liaWe to be passed. -

FEG PA-63 Pistol Extensive User's Instruction and Safety Guide And

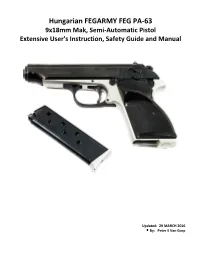

Hungarian FEGARMY FEG PA-63 9x18mm Mak, Semi-Automatic Pistol Extensive User's Instruction, Safety Guide and Manual Updated: 29 MARCH 2016 By: Peter S Van Gorp Table of Contents PAGE …………………………………………………………… ITEM [ click on an item below to jump to its page ] 1 …………………………………………………………………. Cover Page 2 …………………………………………………………………. Table of Contents (this page) 3 …………………………………………………………………. Disclaimer 4 …………………………………………………………………. General Safety Guidelines 5 …………………………………………………………………. Firearm Warnings 6 …………………………………………………………………. Forward, and Historical Background 7 …………………………………………………………………. Historical Background 8 …………………………………………………………………. Historical Background: Pistols 9 …………………………………………………………………. Features, Variants, Implications and Thoughts 10 …………………………………………………………....... Features, Variants, Implications and Thoughts (2) 11 …………………………………………………………....... Features, Variants, Implications and Thoughts (3) 12 …………………………………………………………....... Features, Variants, Implications and Thoughts (4) 13 …………………………………………………………....... Features, Variants, Implications and Thoughts (5) 14 …………………………………………………………....... Features, Variants, Implications and Thoughts (6) 15 …………………………………………………………....... Features, Variants, Implications and Thoughts (7) 16 …………………………………………………………....... Features, Variants, Implications and Thoughts (8) 17 …………………………………………………………....... Features, Variants, Implications and Thoughts (9) 18 …………………………………………………………....... Features, Variants, Implications and Thoughts (10) 19 …………………………………………………………....... Features, Variants, Implications