Bob Was a Shoo-Shoo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National World War I Museum 2008 Accessions to the Collections Doran L

NATIONAL WORLD WAR I MUSEUM 2008 ACCESSIONS TO THE COLLECTIONS DORAN L. CART, CURATOR JONATHAN CASEY, MUSEUM ARCHIVIST All accessions are donations unless otherwise noted. An accession is defined as something added to the permanent collections of the National World War I Museum. Each accession represents a separate “transaction” between donor (or seller) and the Museum. An accession can consist of one item or hundreds of items. Format = museum accession number + donor + brief description. For reasons of privacy, the city and state of the donor are not included here. For further information, contact [email protected] or [email protected] . ________________________________________________________________________ 2008.1 – Carl Shadd. • Machine rifle (Chauchat fusil-mitrailleur), French, M1915 CSRG (Chauchat- Sutter-Ribeyrolles and Gladiator); made at the Gladiator bicycle factory; serial number 138351; 8mm Lebel cartridge; bipod; canvas strap; flash hider (standard after January 1917); with half moon magazine; • Magazine carrier, French; wooden box with hinged lid, no straps; contains two half moon magazines; • Tool kit for the Chauchat, French; M1907; canvas and leather folding carrier; tools include: stuck case extractor, oil and kerosene cans, cleaning rod, metal screwdriver, tension spring tool, cleaning patch holder, Hotchkiss cartridge extractor; anti-aircraft firing sight. 2008.2 – Robert H. Rafferty. From the service of Cpl. John J. Rafferty, 1 Co 164th Depot Brigade: Notebook with class notes; • Christmas cards; • Photos; • Photo postcard. 2008.3 – Fred Perry. From the service of John M. Figgins USN, served aboard USS Utah : Diary; • Oversize photo of Utah ’s officers and crew on ship. 2008.4 – Leslie Ann Sutherland. From the service of 1 st Lieutenant George Vaughan Seibold, U.S. -

Hurricane and Tropical Storm

State of New Jersey 2014 Hazard Mitigation Plan Section 5. Risk Assessment 5.8 Hurricane and Tropical Storm 2014 Plan Update Changes The 2014 Plan Update includes tropical storms, hurricanes and storm surge in this hazard profile. In the 2011 HMP, storm surge was included in the flood hazard. The hazard profile has been significantly enhanced to include a detailed hazard description, location, extent, previous occurrences, probability of future occurrence, severity, warning time and secondary impacts. New and updated data and figures from ONJSC are incorporated. New and updated figures from other federal and state agencies are incorporated. Potential change in climate and its impacts on the flood hazard are discussed. The vulnerability assessment now directly follows the hazard profile. An exposure analysis of the population, general building stock, State-owned and leased buildings, critical facilities and infrastructure was conducted using best available SLOSH and storm surge data. Environmental impacts is a new subsection. 5.8.1 Profile Hazard Description A tropical cyclone is a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or sub-tropical waters and has a closed low-level circulation. Tropical depressions, tropical storms, and hurricanes are all considered tropical cyclones. These storms rotate counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere around the center and are accompanied by heavy rain and strong winds (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA] 2013a). Almost all tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic basin (which includes the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea) form between June 1 and November 30 (hurricane season). August and September are peak months for hurricane development. -

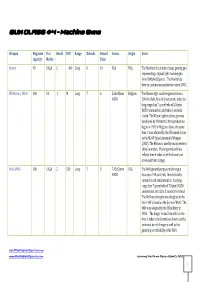

Machine Guns

GUN CLASS #4 – Machine Guns Weapon Magazine Fire Recoil ROF Range Reloads Reload Ammo Origin Notes capacity Modes Time Morita 99 FA,SA 2 400 Long 6 10 N/A N/A The Morita is the standard issue gaming gun representing a typical light machine gun from Battlefield Sports. The Morita has been in continuous manufacture since 2002. FN Minimi / M249 200 FA 2 M Long 7 6 5.56x45mm Belgium The Minimi light machine gun features a NATO 200 shot belt, fires fully automatic only, has long range, has 7 spare belts of 5.56mm NATO ammunition, and takes 6 seconds reload. The Minimi light machine gun was developed by FN Herstal. Mass production began in 1982 in Belgium. About the same time it was adopted by the US Armed forces as the M249 Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW). The Minimi is used by many western allied countries. The longer reload time reflects time it takes to let the barrel cool down and then change. M60 GPMG 100 FA,SA 2 550 Long 7 8 7.62x51mm USA The M60 general purpose machine gun NATO features a 100 shot belt, fires both fully automatic and semiautomatic, has long range, has 7 spare belts of 7.62mm NATO ammunition and takes 8 seconds to reload. The M60 machine gun was designed in the late 1940's based on the German MG42. The M60 was adopted by the US military in 1950. .The longer reload time reflects the time it takes to let barrel cool down and the awkward barrel change as well as the general poor reliability of the M60. -

Protective Force Firearms Qualification Courses

PROTECTIVE FORCE FIREARMS QUALIFICATION COURSES U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY Office of Health, Safety and Security AVAILABLE ONLINE AT: INITIATED BY: http://www.hss.energy.gov Office of Health, Safety and Security Protective Force Firearms Qualification Courses July 2011 i TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION A – APPROVED FIREARMS QUALIFICATION COURSES .......................... I-1 CHAPTER I . INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... I-1 1. Scope .................................................................................................................. I-1 2. Content ............................................................................................................... I-1 CHAPTER II . DOE FIREARMS QUALIFICATION COURSE DEVELOPMENT PROCESS ................................................................................ II-1 1. Purpose ..............................................................................................................II-1 2. Scope .................................................................................................................II-1 3. Process ..............................................................................................................II-1 4. Roles .................................................................................................................II-2 CHAPTER III . GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS FOR FIREARMS QUALIFICATION COURSES.............................................................................III-1 CHAPTER IV -

20 March 2012, Compiled By: Phil Cregeen Pattern: Minimi C 9 LMG

NZART ID: 18 Arm Type: Machine Gun, Date of Draft: (V1) 20 March 2012, Compiled by: Phil Cregeen Pattern: Minimi C 9 LMG Introduced in to NZ Service: 1988, Withdrawn: In Service Maker: Thales, Lithgow Australia, Calibre: 5.56 mm, Cartridge : 5.56x45mm NATO , Magazine: belt or 30 round magazine, Rate of fire: 700 to 1150 rounds per min Barrel length: 465 mm, OA Length: 1038 mm, Height: 270 mm, Width: 110 mm, Weight: 6.48 Kg, Type of Action: Gas-operated, rotating bolt, Sights: rear aperture 300 – 1000 m Minimi C9 Light Machine Gun The 5.56 mm C9 Minimi Light Machine Gun is a fully automatic, air-cooled, gas operated weapon. It fires ammunition from disintegrating link belts or can be fed by magazines. It incorporates an open breech firing system and interchangeable barrels. This gun is the most common within the NZ Army and has been used as the army's Light Support Weapon (LSW) since 1988. The C9 can be converted for parachuting by fitting a carbine (shorter) barrel and collapsible stock, which reduces the overall length of the Standard C9 by 318 mm. The Minimi (short for French: Mini Mitrailleuse; "mini machine gun") is a Belgian 5.56mm light machine gun developed by Fabrique Nationale (FN) in Herstalby Ernest Vervier. First introduced in 1974, it has entered service with the armed forces of over thirty countries. The weapon is currently manufactured at the FN facility in Herstal and their US subsidiary FN Manufacturing LLC, as well as being licence-built in Australia, Italy, Japan, Sweden and Greece. -

CONGR.ESSION AL RECORD-HOUSE. }Lay 31, Bill 2104 Th::Tt We Had up a Few Days Ago, the Purpose of Which 1\Ir

.7234 CONGR.ESSION AL RECORD-HOUSE. }lAY 31, bill 2104 th::tt we had up a few days ago, the purpose of which 1\Ir. 1\IADDEN. Then let us amenu it so that it will say so. i to increa e the salaries of the boiler inspectors. If there is 1\fr. GARRET'".r of Tennessee. For the time being I make a not to be any oppo ition to that bill, it bus been on the calendar point of order on the re olution. for many months, and the department is very much desirous Mr. MADDEN. I do not think the point of order is well taken· to have the legislation enacted. I think the resolution simply asks for facts. It does not ask fo~ 1\Ir. SMOOT. I will say to the Senator from Mississippi that an opinion. It a ks for information which ought to be in I received in thi morning's mail a number of communications pos e sion of the department to which the re olution i ad upon the que tion of steamboat inspectors. I have not yet had dresseti. time to reati them, anti I want the bill to go over at least until The SPE..i.KER. What does the gentleman say about this I can exnmiue the letters which I have already received. language: l\Ir. V .A.RDAMAN. I am not going to urge the consideration That the Interstate Commerce Commi sion be requested to report to of the measure at this time, but it is very necessary that it shall the House the number of men in the s ervice of the commission liaWe to be passed. -

Hurricane & Tropical Storm

5.8 HURRICANE & TROPICAL STORM SECTION 5.8 HURRICANE AND TROPICAL STORM 5.8.1 HAZARD DESCRIPTION A tropical cyclone is a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or sub-tropical waters and has a closed low-level circulation. Tropical depressions, tropical storms, and hurricanes are all considered tropical cyclones. These storms rotate counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere around the center and are accompanied by heavy rain and strong winds (NOAA, 2013). Almost all tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic basin (which includes the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea) form between June 1 and November 30 (hurricane season). August and September are peak months for hurricane development. The average wind speeds for tropical storms and hurricanes are listed below: . A tropical depression has a maximum sustained wind speeds of 38 miles per hour (mph) or less . A tropical storm has maximum sustained wind speeds of 39 to 73 mph . A hurricane has maximum sustained wind speeds of 74 mph or higher. In the western North Pacific, hurricanes are called typhoons; similar storms in the Indian Ocean and South Pacific Ocean are called cyclones. A major hurricane has maximum sustained wind speeds of 111 mph or higher (NOAA, 2013). Over a two-year period, the United States coastline is struck by an average of three hurricanes, one of which is classified as a major hurricane. Hurricanes, tropical storms, and tropical depressions may pose a threat to life and property. These storms bring heavy rain, storm surge and flooding (NOAA, 2013). The cooler waters off the coast of New Jersey can serve to diminish the energy of storms that have traveled up the eastern seaboard. -

Creating a Hurricane Tolerant Community

H!rt a. * am Hef7%e,,, io94 s~ NtA B.6~ «e ( >15 A Hurt a Comlnl Of+ Venice 19 "I t~Y: Oonald C aillOllette IC' i 2w-;vC p %7 iET ! A. 14- C M-i -r CREATING A HURRICANE TOLERANT COMMUNITY TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements . 1 .. Author's Notes . 5 Introduction . 6 Geography of Venice . Coastal Area Redevelopment Plan . 26 Venice Compliance Program . 62 Developing a Tolerant Building. 104 Hurricane Damage Prevention Project. .118 Growing Native for Nature ................. 136 Hurricane Defense Squadron . ............... 148 Executive Summary ..................... 157 A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S This pilot study was contracted through the State of Florida and was made possible by funding provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). William Massey and Eugene P. Zeizel, Ph.D. of FEMA and Michael McDonald with the Florida Department of Community Affairs were all instrumental in developing the scope of work and funding for this study. Special thanks go to the Venice City Council and City Manager George Hunt for their approval and support of the study. MAYOR: MERLE L. GRASER CITY COUNCIL: EARL MIDLAM, VICE MAYOR CHERYL BATTEY ALAN McEWEN DEAN CALAMARAS BRYAN HOLCOMB MAGGIE TURNER A study of this type requires time for the gathering of information from a variety of sources along with the assembling of these resources into a presentable format. Approximately six months were needed for the development of this study. The Venice Planning Department consisting of Chuck Place, Director, and Cyndy Powers need to be recognized for their encouragement and support of this document from the beginning to the end. -

Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms

FLORIDA HURRICANES AND TROPICAL STORMS 1871-1995: An Historical Survey Fred Doehring, Iver W. Duedall, and John M. Williams '+wcCopy~~ I~BN 0-912747-08-0 Florida SeaGrant College is supported by award of the Office of Sea Grant, NationalOceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce,grant number NA 36RG-0070, under provisions of the NationalSea Grant College and Programs Act of 1966. This information is published by the Sea Grant Extension Program which functionsas a coinponentof the Florida Cooperative Extension Service, John T. Woeste, Dean, in conducting Cooperative Extensionwork in Agriculture, Home Economics, and Marine Sciences,State of Florida, U.S. Departmentof Agriculture, U.S. Departmentof Commerce, and Boards of County Commissioners, cooperating.Printed and distributed in furtherance af the Actsof Congressof May 8 andJune 14, 1914.The Florida Sea Grant Collegeis an Equal Opportunity-AffirmativeAction employer authorizedto provide research, educational information and other servicesonly to individuals and institutions that function without regardto race,color, sex, age,handicap or nationalorigin. Coverphoto: Hank Brandli & Rob Downey LOANCOPY ONLY Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms 1871-1995: An Historical survey Fred Doehring, Iver W. Duedall, and John M. Williams Division of Marine and Environmental Systems, Florida Institute of Technology Melbourne, FL 32901 Technical Paper - 71 June 1994 $5.00 Copies may be obtained from: Florida Sea Grant College Program University of Florida Building 803 P.O. Box 110409 Gainesville, FL 32611-0409 904-392-2801 II Our friend andcolleague, Fred Doehringpictured below, died on January 5, 1993, before this manuscript was completed. Until his death, Fred had spent the last 18 months painstakingly researchingdata for this book. -

Assessing Interactions Between Estuary Water Quality and Terrestrial Land Cover in Hurricane Events with Multi-Sensor Remote Sensing

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2017 Assessing Interactions between Estuary Water Quality and Terrestrial Land Cover in Hurricane Events with Multi-sensor Remote Sensing Chandan Mostafiz University of Central Florida Part of the Environmental Engineering Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Mostafiz, Chandan, Assessing" Interactions between Estuary Water Quality and Terrestrial Land Cover in Hurricane Events with Multi-sensor Remote Sensing" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5688. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5688 ASSESSING INTERACTIONS BETWEEN ESTUARY WATER QUALITY AND TERRESTRIAL LAND COVER IN HURRICANE EVENTS WITH MULTI-SENSOR REMOTE SENSING by CHANDAN MOSTAFIZ B.S. Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, 2014 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Department of Civil, Environmental, and Construction Engineering in the College of Engineering and Computer Science at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2017 Major Professor: Ni-Bin Chang © 2017 Chandan Mostafiz ii ABSTRACT Estuaries are environmentally, ecologically and environmentally important places as they act as a meeting place for land, freshwater and marine ecosystems. They are also called nurseries of the sea as they often provide nesting and feeding habitats for many aquatic plants and animals. -

Mg 34 and Mg 42 Machine Guns

MG 34 AND MG 42 MACHINE GUNS CHRIS MC NAB © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com MG 34 AND MG 42 MACHINE GUNS CHRIS McNAB Series Editor Martin Pegler © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 DEVELOPMENT 8 The ‘universal’ machine gun USE 27 Flexible firepower IMPACT 62 ‘Hitler’s buzzsaw’ CONCLUSION 74 GLOSSARY 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY & FURTHER READING 78 INDEX 80 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com INTRODUCTION Although in war all enemy weapons are potential sources of fear, some seem to have a deeper grip on the imagination than others. The AK-47, for example, is actually no more lethal than most other small arms in its class, but popular notoriety and Hollywood representations tend to credit it with superior power and lethality. Similarly, the bayonet actually killed relatively few men in World War I, but the sheer thought of an enraged foe bearing down on you with more than 30cm of sharpened steel was the stuff of nightmares to both sides. In some cases, however, fear has been perfectly justified. During both world wars, for example, artillery caused between 59 and 80 per cent of all casualties (depending on your source), and hence took a justifiable top slot in surveys of most feared tools of violence. The subjects of this book – the MG 34 and MG 42, plus derivatives – are interesting case studies within the scale of soldiers’ fears. Regarding the latter weapon, a US wartime information movie once declared that the gun’s ‘bark was worse than its bite’, no doubt a well-intentioned comment intended to reduce mounting concern among US troops about the firepower of this astonishing gun. -

Massachusetts Tropical Cyclone Profile August 2021

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Tropical Cyclone Profile August 2021 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Tropical Cyclone Profile Description Tropical cyclones, a general term for tropical storms and hurricanes, are low pressure systems that usually form over the tropics. These storms are referred to as “cyclones” due to their rotation. Tropical cyclones are among the most powerful and destructive meteorological systems on earth. Their destructive phenomena include storm surge, high winds, heavy rain, tornadoes, and rip currents. As tropical storms move inland, they can cause severe flooding, downed trees and power lines, and structural damage. Once a tropical cyclone no longer has tropical characteristics, it is then classified as a post-tropical system. The National Hurricane Center (NHC) has classified four stages of tropical cyclones: • Tropical Depression: A tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of 38 mph (33 knots) or less. • Tropical Storm: A tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of 39 to 73 mph (34 to 63 knots). • Hurricane: A tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of 74 mph (64 knots) or higher. • Major Hurricane: A tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of 111 mph (96 knots) or higher, corresponding to a Category 3, 4 or 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. Primary Hazards Storm Surge and Storm Tide Storm surge is an abnormal rise of water generated by a storm, over and above the predicted astronomical tide. Storm surge and large waves produced by hurricanes pose the greatest threat to life and property along the coast. They also pose a significant risk for drowning. Storm tide is the total water level rise during a storm due to the combination of storm surge and the astronomical tide.