“Second Choices”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catullus, Memmius, and Bithynia

Catullus, Memmius, and Bithynia Gaius Memmius was the son-in-law of Sulla, an orator who won backhanded praise from Cicero (Brut. 247), seducer of the wife of Marcus Lucullus (Cic. Att. 1. 18. 3) and a fierce adversary of his brother (Plut. Cat. Mi. 29. 5-8), a poet whose immodesty impressed Ovid (Tr. 2. 433), a praetor (Cic. Q. fr. 1. 2. 16), a candidate for the consulship, a disgraced exile, the probable but imperfect patron of Lucretius, and a perfect villain for Catullus, and a successful military commander, hailed by his troops as “Imperator.” The last is evidenced by a denarius (427 Crawford). The obverse presents the head of Ceres, facing right, with C∙ MEMMI C ∙ F ∙ reading downwards. On the reverse is a trophy and a kneeling captive with hands tied behind his back; reading downwards on the left is the title IMPERATOR and on the right C ∙ MEMMIUS. To my knowledge this remarkable coin is never brought up in discussions of Catullus, despite the fact that Catullus would have been serving in the cohors of Memmius at the time he was acclaimed imperator. Crawford and others date the coin to 56, following the consensus that Memmius was governor of Bithynia in 57. This presents a problem, for it seems unlikely that Memmius could have engaged in any significant military campaign nine years after the province had been pacified (Cic. Agr. 2. 47) and a full five years after Pompey’s settlement of the East. It is much more likely that Memmius’ victory was earlier, at a time when there was still potential unrest in the area of Bithynia following Mithradates’ resurgence in 67. -

THE GEOGRAPHY of GALATIA Gal 1:2; Act 18:23; 1 Cor 16:1

CHAPTER 38 THE GEOGRAPHY OF GALATIA Gal 1:2; Act 18:23; 1 Cor 16:1 Mark Wilson KEY POINTS • Galatia is both a region and a province in central Asia Minor. • The main cities of north Galatia were settled by the Gauls in the third cen- tury bc. • The main cities of south Galatia were founded by the Greeks starting in the third century bc. • Galatia became a Roman province in 25 bc, and the Romans established colonies in many of its cities. • Pamphylia was part of Galatia in Paul’s day, so Perga and Attalia were cities in south Galatia. GALATIA AS A REGION and their families who migrated from Galatia is located in a basin in north-cen- Thrace in 278 bc. They had been invited tral Asia Minor that is largely flat and by Nicomedes I of Bithynia to serve as treeless. Within it are the headwaters of mercenaries in his army. The Galatians the Sangarius River (mode rn Sakarya) were notorious for their destructive and the middle course of the Halys River forays, and in 241 bc the Pergamenes led (modern Kızılırmak). The capital of the by Attalus I defeated them at the battle Hittite Empire—Hattusha (modern of the Caicus. The statue of the dying Boğazköy)—was in eastern Galatia near Gaul, one of antiquity’s most noted the later site of Tavium. The name Galatia works of art, commemorates that victo- derives from the twenty thousand Gauls ry. 1 The three Galatian tribes settled in 1 . For the motif of dying Gauls, see Brigitte Kahl, Galatians Re-imagined: Reading with the Eyes of the Vanquished (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2010), 77–127. -

Ebru N. AKDOĞU ARCA* New Inscriptions from Bithynia

GEPHYRA 4 2007 145–154 Ebru N. AKDOĞU ARCA* New Inscriptions From Bithynia Abstract: In this article one unpublished Greek dedication inscription from Beyyayla dated to the third century A.D. and eight unpublished funerary Greek inscriptions from Bithynia dated to the Roman Imperial Period are presented. Four funerary inscriptions are of the doorstone type. Six funerary inscriptions are from Nikaia – the curve of the middle Sangarios (Göynük, Gölpazarı, Taraklı and Geyve) –, one is from Prusa ad Olympum and one is from Claudiopolis. Copies and photographs of the inscriptions were taken by Prof. Dr. Sencer Şahin in the 1980’s while he was surveying in Bithynia. Information concerning those inscriptions was obtained from the notes which were taken by him at that time. The inscriptions are as follows. 1) A dedication to Zeus (H?)iarazaios from Beyyayla1 White limestone altar. Found in Arpalık, ca. 500 m south west of Beyyayla, in front of the house of Ali Şahin. Dimensions: H. 0.68 m, W. 0.26 m, D. 0.22 m, L. 0.021 m. All corners of the stone are damaged and some of them are broken. Due to this, only small fragments of the acroteria are pre- served. There is a rosette motif carved in the middle and nearly upon the profile. On the right and left side, in the middle of the acro- teria is carved a boukephalos. There are tendrils on the both side of the boukephalos. The inscription begins fairly under the profile and consists of three lines. The inscription is complete and well- preserved. -

Two Phrygian Gods Between Phrygia and Dacia1

Colloquium Anatolicum 2016 / 15 Keywords: Zeus Surgastes, Zeus Sarnendenos, gods, Phrygia, Galatia, Roman Dacia. Two Phrygian Gods Between Phrygia The author discusses the cult of Zeus Syrgastes (Syrgastos) and Zeus Sarnendenos and points out 1 and Dacia that both are of Phrygian uorigin. For Syrgastes evidence from Old Phrygian records must be added, which proves that this god was long established and had possibly Hittite-Luwian roots. Zeus Sarnendenos seems to be more recent and his mother-country may be sought in north-east Phrygia / north-west Galatia. Both cults were brought to Roman Dacia by colonists coming from Bithynia, possibly from the area of Tios/Hadrianopolis (for Zeus Syrgastes) and Galatia, perhaps from the area of modern-day Mihalıcçık (for Zeus Sarnendenos). Alexandru AVRAM2 Anahtar Kelimeler: Zeus Surgastes, Zeus Sarnendenos, Tanrılar, Phrygia, Galatia, Dacia. |70| Bu makalede Zeus Syrgastes (Syrgastos) and Zeus Sarnendenos kültleri ve bu kültlerin her iki- |71| sinin de Frigya kökenli oldukları tartışılmaktadır. Syrgastes ile ilgili kaynaklar arasında Eski Frig kaynakları bulunmaktadır ki bu durum bize bu tanrının kökenlerinin çok eskiye dayan- dığını, muhtemelen Hitit-Luwi kökenlerine sahip olduğunu göstermektedir. Zeus Sarnendenos daha genç bir tanrı olarak gözükmektedir ve anayurdu muhtemelen kuzey-doğu Frigya / ku- zey-batı Galatia olabilir. Muhtemelen her iki kült de Roma Dacia’sına bugünkü Bithynia’dan, Tios/Hadrianopolis (Zeus Syrgastes için) bölgesinden ve Galatia’dan, muhtemelen modern Mihalıcçık (Zeus Sarnendenos için) civarından gelen yerleşimcilerce getirilmiştir. 1 Hakeme Gönderilme Tarihi: 10.05.2016 ve 30.09.2016; Kabul Tarihi: 09.06.2016 ve 03.10.2016. 2 Alexandru AVRAM. Université du Maine, Faculté des Lettres, Langues et Sciences humaines, Avenue Olivier Messiaen, 72000 Le Mans, France. -

7 the Roman Empire

Eli J. S. Weaverdyck 7 The Roman Empire I Introduction The Roman Empire was one of the largest and longest lasting of all the empires in the ancient world.1 At its height, it controlled the entire coast of the Mediterranean and vast continental hinterlands, including most of western Europe and Great Brit- ain, the Balkans, all of Asia Minor, the Near East as far as the Euphrates (and be- yond, briefly), and northern Africa as far south as the Sahara. The Mediterranean, known to the Romans as mare nostrum(‘our sea’), formed the core. The Mediterranean basin is characterized by extreme variability across both space and time. Geologically, the area is a large subduction zone between the African and European tectonic plates. This not only produces volcanic and seismic activity, it also means that the most commonly encountered bedrock is uplifted limestone, which is easily eroded by water. Much of the coastline is mountainous with deep river valleys. This rugged topography means that even broadly similar climatic conditions can pro- duce drastically dissimilar microclimates within very short distances. In addition, strong interannual variability in precipitation means that local food shortages were an endemic feature of Mediterranean agriculture. In combination, this temporal and spatial variability meant that risk-buffering mechanisms including diversification, storage, and distribution of goods played an important role in ancient Mediterranean survival strategies. Connectivity has always characterized the Mediterranean.2 While geography encouraged mobility, the empire accelerated that tendency, inducing the transfer of people, goods, and ideas on a scale never seen before.3 This mobility, combined with increased demand and the efforts of the imperial govern- ment to mobilize specific products, led to the rise of broad regional specializations, particularly in staple foods and precious metals.4 The results of this increased con- It has also been the subject of more scholarship than any other empire treated in this volume. -

CAESAR and NICOMEDES”, the Classical Quarterly, 58(2), Pp

Georgetown University Institutional Repository http://www.library.georgetown.edu/digitalgeorgetown The author made this article openly available online. Please tell us how this access affects you. Your story matters. OSGOOD, J. (2008) “CAESAR AND NICOMEDES”, The Classical Quarterly, 58(2), pp. 687–691. doi: 10.1017/S0009838808000785 Collection Permanent Link: http://hdl.handle.net/10822/551722 © 2008 The Classical Association This material is made available online with the permission of the author, and in accordance with publisher policies. No further reproduction or distribution of this copy is permitted by electronic transmission or any other means. SHORTER NOTES 687 CAESAR AND NICOMEDES Around 80 B.C., as a young man of about twenty years, Julius Caesar left Rome to join the staff of M. Minucius Thermus in Asia for military training. Thermus was busy with the subjugation of Mytilene, the last of the cities of Asia to hold out against Rome after the recent war with Mithridates, and sent Caesar to fetch a fleet from King Nicomedes IV of Bithynia. Suetonius (Iul. 2) reports that Caesar dawdled at the royal court, so that a rumour crept up of sexual congress with the king (prostratae regi pudicitiae); and the rumour only grew when a few days after his mission was accomplished, Caesar returned to Bithynia ‘on the pretext of collecting money which was owed to a certain freedman, a client of his’ (per causam exigendae pecuniae, quae deberetur cuidam libertino clienti suo). Certainly, later in life the Roman was regularly accused of having shared the king’s bed, and in a remarkable chapter of his biography (Iul. -

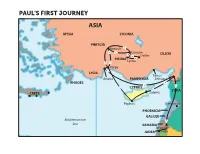

Paul's First Journey

PAUL’S FIRST JOURNEY ASIA MYSIA LYCONIA PHRYGIA Antioch Iconium CILICIA Derbe PISIDIA Lystra Perga LYCIA Tarsus Attalia PAMPHYLIA Seleucia Antioch RHODES CYPRUS SYRIA CRETE Salamis Paphos Damascus PHOENICIA GALILEE Mediterranean Sea SAMARIA Jerusalem JUDEA Gaza PAUL’S SECOND JOURNEY Neapolis Philippi BITHYNIA Amphipolis MACEDONIA Thessalonica CAPPADOCIA Berea Troas ASIA GALATIA GREECE Aegean MYSIA LYCAONIA ACHAIA Sea PHRYGIA Athens Corinth Ephesus Iconium Cenchreae Trogylliun PISIDIA Derbe CILICIA Lystra LYCIA PAMPHYLIA Antioch RHODES CYPRUS SYRIA CRETE Paphos PHOENICIA Mediterranean Sea GALILEE Caesarea SAMARIA Jerusalem JUDEA PAUL’S THIRD JOURNEY Philippi BITHYNIA MACEDONIA Thessalonica CAPPADOCIA Berea Aegean Troas ASIA GALATIA Assos GREECE Sea MYSIA LYCAONIA ACHAIA Chios Mitylene PHRYGIA Antioch Corinth Ephesus PISIDIA CILICIA Samos Miletus Colossae LYCIA Kos PAMPHYLIA Patara RHODES Antioch CYPRUS SYRIA CRETE PHOENICIA Tyre Mediterranean GALILEE Sea Ptolemais Caesarea SAMARIA Jerusalem JUDEA PAUL’S THIRD JOURNEY Philippi BITHYNIA MACEDONIA Thessalonica CAPPADOCIA Berea Aegean Troas ASIA GALATIA Assos GREECE Sea MYSIA LYCAONIA ACHAIA Chios Mitylene PHRYGIA Antioch Corinth Ephesus PISIDIA CILICIA Samos Miletus Colossae LYCIA Kos PAMPHYLIA Patara Antioch RHODES CYPRUS SYRIA CRETE PHOENICIA Tyre Mediterranean GALILEE Sea Ptolemais Caesarea SAMARIA Jerusalem JUDEA PAUL’S JOURNEY TO ROME DALMATIA Black Sea Adraitic THRACE ITALY Sea ROME MACEDONIA Three Taverns PONTUS Appii Forum Pompeii BITHYNIA Puteoli ASIA GREECE Agean Sea Tyrrhenian MYSIA Sea ACHAIA PHRYGIA CAPPADOCIA GALATIA LYCAONIA Ionian Sea PISIDIA SICILY Rhegium CILICIA Syracuse LYCIA PAMPHYLIA CRETE Myca RHODES MALTA SYRIA (MELITA) Clauda Fort CYPRUS Havens Mediterranean Sea PHOENICIA GALILEE Caesarea SAMARIA Antipatris CYRENAICA Jerusalem TRIPOLITANIA LIBYA JUDEA EGYPT. -

Bithynia Tentaculata) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Faucet Snail (Bithynia tentaculata) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, February 2011 Revised, September 2014 Revised, July 2015 Photo: Amy Benson, USGS 1 Native Range, and Status in the United States Native Range From Kipp et al. (2015): “Europe, from Scandinavia to Greece.” Status in the United States From Kipp et al. (2015): “The species is established in the drainages of Lake Ontario (Mills et al. 1993; Peckarsky et al. 1993), Lake Michigan (Mills et al. 1993), and Lake Erie (Krieger 1985; Mackie et al. 1980; Peckarsky et al. 1993), but not Lake Superior (Jokinen 1992). Occurrences in Lake Huron do not warrant classification as established.” “Great Lakes Region: Bithynia tentaculata was first recorded in Lake Michigan in 1871, but was probably introduced in 1870 (Mills et al. 1993). It spread to Lake Ontario by 1879, the Hudson River by 1892, and other tributaries and water bodies in the Finger Lakes region during the 20th century (Jokinen 1992; Mills et al. 1993). It was introduced to Lake Erie sometime before 1930 (Carr and Hiltunen 1965; Krieger 1985). This snail’s range now extends from Quebec and Wisconsin to Pennsylvania and New York (Jokinen 1992). It has been recorded from Lake Huron, but only a few individuals were found in benthic samples from Saginaw Bay in the 1980s and 1990s (Nalepa et al. 2002).” Means of Introductions in the United States From Kipp et al. (2015): “Bithynia tentaculata could have been introduced to the Great Lakes basin in packaging material for crockery, through solid ballast in timber ships arriving to Lake Michigan, or by deliberate release by amateur naturalists into the Erie Canal, Mohawk River and Schuyler’s Lake (Mills et al. -

Map 86 Paphlagonia Compiled by C

Map 86 Paphlagonia Compiled by C. Foss, 1995 Introduction The map comprises ancient Paphlagonia, and extends into eastern Bithynia and the northernmost part of Galatia. Evidence for the ancient topography is most abundant on the coast, along the Roman roads, and in Galatia. Arrian’s Periplus Ponti Euxini (written c. A.D. 132), together with an earlier text by Menippus (c. 20 B.C.) and a related Late Antique anonymous work, describe the coast in great detail. Most of the sites named in these works can be located at least approximately, although a few resist identification; Müller’s commentary in GGM I remains valuable. For the Roman roads, ItMiller is uncritical; French (1981) is far more useful, but treats only one major road. The roads of Paphlagonia are presented in admirable detail by TIB Paphlagonien, those of northern Galatia likewise by TIB Galatien. The interior of Paphlagonia is a remote, mountainous country, cut off from the regions to the south by long, parallel ranges. Communication east and west is relatively easy; north and south, it is much more difficult. The country contains a few long, wide plains and river valleys, some of considerable fertility. In antiquity, the mountains were heavily forested. For the most part, the region was never densely populated. For a general description, see Leonhard (1915); and for an excellent account of some areas (including eastern Bithynia), with discussion of specific problems, note Robert (1980). RE Paphlagonia gives a full list of all named sites (cols. 2537-50) and of physical remains (2498-2510, 2515). Some features listed there do not appear on the map because of limited significance or uncertainty of dating. -

Ancient Rome and Early Christianity, 500 B.C.-A.D. 500

Ancient Rome and Early Christianity, 500 B.C.-A.D. 500 Previewing Main Ideas POWER AND AUTHORITY Rome began as a republic, a government in which elected officials represent the people. Eventually, absolute rulers called emperors seized power and expanded the empire. Geography About how many miles did the Roman Empire stretch from east to west? EMPIRE BUILDING At its height, the Roman Empire touched three continents—Europe, Asia, and Africa. For several centuries, Rome brought peace and prosperity to its empire before its eventual collapse. Geography Why was the Mediterranean Sea important to the Roman Empire? RELIGIOUS AND ETHICAL SYSTEMS Out of Judea rose a monotheistic, or single-god, religion known as Christianity. Based on the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, it soon spread throughout Rome and beyond. Geography What geographic features might have helped or hindered the spread of Christianity throughout the Roman Empire? INTERNET RESOURCES • Interactive Maps Go to classzone.com for: • Interactive Visuals • Research Links • Maps • Interactive Primary Sources • Internet Activities • Test Practice • Primary Sources • Current Events • Chapter Quiz 152 153 What makes a successful leader? You are a member of the senate in ancient Rome. Soon you must decide whether to support or oppose a powerful leader who wants to become ruler. Many consider him a military genius for having gained vast territory and wealth for Rome. Others point out that he disobeyed orders and is both ruthless and devious. You wonder whether his ambition would lead to greater prosperity and order in the empire or to injustice and unrest. ▲ This 19th-century painting by Italian artist Cesare Maccari shows Cicero, one of ancient Rome’s greatest public speakers, addressing fellow members of the Roman Senate. -

Graeco-Roman Associations, Judean Synagogues and Early Christianity in Bithynia-Pontus*

chapter 3 Graeco-Roman Associations, Judean Synagogues and Early Christianity in Bithynia-Pontus* Markus Öhler As has been shown in numerous studies, early Christian communities as well as synagogues of Judeans resemble Graeco-Roman associations in form and structure. Therefore, it makes sense to examine Christ groups from the first three centuries from the perspective of associations and synagogues in order to grasp the various characteristics of Christianity in this area up until the reign of Constantine. This article will begin with a brief geographical and historical overview of the regions composing the double province of Bithynia-Pontus, continue with a review of the inscriptional and literary evidence on associa- tions (including synagogues), and finally discuss early sources for a study of Christianity, namely, the New Testament, Pliny’s letter about Christians, and inscriptions from the second and third centuries with a potentially Christian background. 1 Bithynia and Pontus: The Area and Its History in Early Imperial Times The area of Bithynia et Pontus, which partly includes the region of Paphlagonia, has had a chequered history.1 In what follows, I will roughly focus on the territo- ries which formed a Roman double province from 63BC onward. This includes, from west to east, the region of Bithynia (from Kalchedon to Klaudiopolis and Tieion), Paphlagonia (from Amastris to Sinope), and Pontus (from Amisos to Nikopolis). Pontus had been a kingdom from Mithradates I until the death of Mithra- dates VI in 63BC. Afterwards, the western part, reaching as far as the city of Nikopolis, became part of the Roman province of Bithynia et Pontus which * Many thanks to Julien M. -

The Local Impact of the Koinon in Roman Coastal Paphlagonia Chingyuan Wu University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 The Local Impact Of The Koinon In Roman Coastal Paphlagonia Chingyuan Wu University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Wu, Chingyuan, "The Local Impact Of The Koinon In Roman Coastal Paphlagonia" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3204. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3204 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3204 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Local Impact Of The Koinon In Roman Coastal Paphlagonia Abstract This dissertation studies the effects that a “koinon” in the Roman period could have on its constituent communities. The tudys traces the formation process of the koinon in Roman coastal Paphlagonia, called “the Koinon of the Cities in Pontus,” and its ability to affect local customs and norms through an assortment of epigraphic, literary, numismatic and archaeological sources. The er sults of the study include new readings of inscriptions, new proposals on the interpretation of the epigraphic record, and assessments on how they inform and change our opinion regarding the history and the regional significance of the coastal Paphlagonian koinon. This study finds that the Koinon of the Cities in Pontus in coastal Paphlagonia was a dynamic organisation whose membership and activities defined by the eparchic administrative boundary of the Augustan settlement and the juridical definition of the Pontic identity in the eparchic sense. The necessary process that forced the periodic selection of municipal peers to attain koinon leadership status not only created a socially distinct category of “koinon” elite but also elevated the koinon to extraordinary status based on consensus in the eparchia.