STS 145 Game Review: Wipeout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

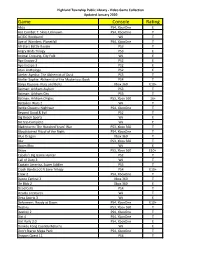

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Course Organization CISC 877 Video Game Development Week 1: Introduction

Course Organization CISC 877 Video Game Development Week 1: Introduction T.C. Nicholas Graham [email protected] http://equis.cs.queensu.ca/wiki/index.php/CISC_877 Winter term, 2010 equis: engineering interactive systems Topics include… Timeline and Marking Scheme Video game design Gaminggp platforms and fundamental technolo gies Activity Due Date Grade January 26, Game development processes and pipeline Project Proposal (2-3 pages, hand-in) 10% 2010 Software architecture of video games Progress Presentation (involves Mar 2, 2010 20% Video games as distributed systems presentation and online report) Game physics Informal progress reports Weekly 5% GAIGame AI April 6, 2010 Scripting languages Final Project Presentation / Show 10% (tentative) Game development tools Final Project Report April 9, 2010 45% Social and ethical aspects of video games Class Participation 10% User in terf aces of gam es equis: engineering interactive systems equis: engineering interactive systems Homework Project proposal (for next week) Wiki contains detailed description of project ideas, game you will be extending The Project Proposal to be posted on Wiki – create yourself an account Form your own project groups – pick project appropriate to group size OGRE tutorials (over next two weeks) …see Wiki for details Download URL: http://equis.cs.queensu.ca/~graham/cisc877/soft/ equis: engineering interactive systems equis: engineering interactive systems The Game: Life is a Village The Game: Life is a Village Goal is to build an interesting village -

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

Michelin to Make Playstation's Gran

PRESS INFORMATION NEW YORK, Aug. 23, 2019 — PlayStation has selected Michelin as “official tire technology partner” for its Gran Turismo franchise, the best and most authentic driving game, the companies announced today at the PlayStation Theater on Broadway. Under the multi-year agreement, Michelin also becomes “official tire supplier” of FIA Certified Gran Turismo Championships, with Michelin-branded tires featured in the game during its third World Tour live event also in progress at PlayStation Theater throughout the weekend. The relationship begins by increasing Michelin’s visibility through free downloadable content on Gran Turismo Sport available to users by October 2019. The Michelin-themed download will feature for the first time: . A new Michelin section on the Gran Turismo Sport “Brand Central” virtual museum, which introduces players to Michelin’s deep history in global motorsports, performance and innovation. Tire technology by Michelin available in the “Tuning” section of Gran Turismo Sport, applicable to the game’s established hard, medium and soft formats. On-track branding elements and scenography from many of the world’s most celebrated motorsports competitions and venues. In 1895, the Michelin brothers entered a purpose-built car in the Paris-Bordeaux-Paris motor race to prove the performance of air-filled tires. Since that storied race, Michelin has achieved a record of innovation and ultra-high performance in the most demanding and celebrated racing competitions around the world, including 22 consecutive overall wins at the iconic 24 Hours of Le Mans and more than 330 FIA World Rally Championship victories. Through racing series such as FIA World Endurance Championship, FIA World Rally Championship, FIA Formula E and International Motor Sports Association series in the U.S., Michelin uses motorsports as a laboratory to collect vast amounts of real-world data that power its industry-leading models and simulators for tire development. -

Printing from Playstation® 2 / Gran Turismo 4

Printing from PlayStation® 2 / Gran Turismo 4 NOTE: • Photographs can be taken within the replay of Arcade races and Gran Turismo Mode. • Transferring picture data to the printer can be via a USB lead between each device or USB storage media (Sony Computer Entertainment Australia Pty Ltd recommends the Sony Micro Vault ™) • Photographs can only be taken in SINGLE PLAYER mode. Photographs in Gran Turismo Mode Section 1. Taking Photo - Photo Travel (refer Gran Turismo Instruction Manual – Photo Travel) In the Gran Turismo Mode main screen go to Photo Travel (this is in the upper left corner of the map). Select your city, configure the camera angle, settings, take your photo and save your photo. Section 2. Taking Photo – Replay Theatre (refer Gran Turismo Instruction Manual) In the Gran Turismo Mode main scre en go to Replay Theatre (this is in the bottom right of the map). Choose the Replay file. Choose Play. The Replay will start. Press the Select during the replay when you would like to photograph the race. This will take you into Photo Shoot . Configure the camera angle, settings, take your photo and save your photo. Section 3. Printing a Photo – Photo Lab (refer Gran Turismo Instruction Manual) Connect the Epson printer to one of the USB ports on your PlayStation 2. Make sure there is paper in the printer. In the Gran Turismo Mode main screen select Home. Go to the Photo Lab. Go to Photo (selected from the left side). Select the photos you want to print. Choose the Print Icon ( the small printer shaped on the right-hand side of the screen) this will add the selected photos to the Print Folder. -

Grafický Dizajn a Kolaborácia Diplom Ant: Katarína Balážiková Vysoká Škola Výtvarných Umení V Bratislave Vedúci Dipl

Vysoká škola výtvarných umení v Bratislave Katedra teórie a dejín umenia grafický dizajn a kolaborácia Diplomant: Katarína Balážiková Vedúci diplomovej práce: Doc. PhDr. Z. Kolesár, PhD. Bratislava, akademický rok 2005/06 Vysoká škola výtvarných umení v Bratislave Katedra teórie a dejín umenia grafický dizajn a kolaborácia Diplomant: Katarína Balážiková Vedúci diplomovej práce: Doc. PhDr. Z. Kolesár, PhD. „Jeden je biely, druhý je čierny. Cesta jedného nikdy neskríži cestu druhého. Jeden vie, čo robí druhý. Každý z nich hovorí inou rečou, ale dobre si rozumejú. Jeden rešpektuje druhého. Jeden je dobro, druhý je zlo. Jeden je druhý, ale nikdy nie v rovnakom čase.“ <Dimitri Bruni, Manuel Krebs - NORM> Poďakovanie: Doc.L. Čarnému, Julovi Nagyovi, Palovi Bálikovi, Kristianovi Lukičovi, Branke Čurčič a Olge Hošekovej Some rights reserved. Text je publikovný licenciou Creative Commons, ak nie je uvedené inak. Licencia : Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 2.5 , http://creativecommons.org/licences/by-nc-sa/2.5/ Bratislava, akademický rok 2005/2006 1. Úvod / 4-5 2. Kolaborácia v súvislostiach / 6-19 2.1. Kolaborácia v histórii výtvarného umenia 2.2. Kolaborácia ako sociologický fenomén 2.3. Kolaborácia ako kolektívna inteligencia 2.4. Kolaborácia a individualita 2.5. Kolaborácia a autor 2.6. Kolaborácia a veda 2.7. Kolaborácia ako hra 2.8. Kolaborácia a otvorenosť 2.9. Kolaborácia a jej odvrátená strana 3. Kolaborácia v pojmoch / 20-27 3.1. Forma 3.2. Hierarchia 3.3. Médium 3.4. Model 4. Dejiny kolaborácie v grafickom dizajne / 28-37 5. Kolaborácia a nové médiá / 38-41 6. Záver / 42-43 7. Bibliografia / 44-45 4 =1+1 1.Úvod nosť a exotickosť spojenia tohto pojmu s profesiou grafického dizajnéra aj napriek stále sa rozširujúcej tendencii kapitalizmom núteného dizajnéra-jednica zoskupovať sa pod tlakom konkurencie. -

Ps4 Architecture

PS4 ARCHITECTURE JERRY AFFRICOT OVERVIEW • Evolution of game consoles • PlayStation History • CPU Architecture • GPU architecture • System Memory • Future of the PlayStation EVOLUTION OF GAME CONSOLES • 1967 • First video game console with two attached controllers • Invented by Ralph Baer • Only six simple games: ping-pong, tennis, handball, volleyball, chase games, light-gun games • 1975-1977 • Magnavox Odyssey consoles • Same games with better graphics, controllers. EVOLUTION OF GAME CONSOLES (continued) • 1978-1980 • First Nintendo video gaming consoles • First color TV game series sold only in Japan • 1981-1985 • Development of games like fighting, platform, adventure and RPG • Classic games: • Pac-man, Mario Bros, the Legend of Zelda etc. EVOLUTION OF GAMES CONSOLES (continued) • 1986-1990 • Mega Drive/Genesis • Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) • 1991-1993 • Compact discs • Transition of 2D graphics to that of 3D graphics • First CD console launched by Philips (1991) EVOLUTION OF GAME CONSOLES (continued) • 1994-1997 • PlayStation release • Nintendo 64 (still using cartridges) • 1998-2004 • PlayStation 2 • GameCube • Xbox featuring Xbox Live HISTORY OF THE PLAYSTATION • PlayStation (1994) • PS1 (2000) • Smaller version of the PlayStation • PS2 (2000) • Backward compatible with most PS1 games • PS2 Slim line (2004) • Smaller version of the PS2 HISTORY OF THE PLAYSTATION (continued) • PSP (2004) • PS3 (2006) • First console to introduce use of motion sensing technology • Slimmer model released in 2009 • PSP Go (2009) • PS -

A Beginners Guide to SUPER GT IT’S AWESOME! Introduction to SUPER GT

A Beginners Guide to SUPER GT IT’S AWESOME! Introduction to SUPER GT UPER GT is the Japan's ■Full of world-class star drivers and team directors in SUPER GT premier touring car series S Drivers participating in SUPER GT are well be ranked among the world top featuring heavily-modified drivers. Many of them started their career from junior karting competitions, production cars (and cars that eventually stepped up into higher racing categories. Just as with baseball and are scheduled to be commercially football, SUPER GT has many world-class talents from both home and abroad. available). GT stands for Grand Furthermore, most teams appoint former drivers to team directors who have Touring - a high-performance car that is capable of high speed and achieved successful career in the top categories including Formula One and long-distance driving. SUPER GT is the 24 Hours of Le Mans. This has made the series establish a leading position a long-distance competition driven in the Japanese motor racing, creating even more exciting and dramatic battles by a couple of drivers per team to attracts millions of fans globally. sharing driving duties. The top class GT500 has undergone a big ■You don’t want to miss intense championship battles! transformation with new cars and regulations. The year 2014 is an In SUPER GT, each car is driven by two inaugural season in which the basic drivers sharing driving duties. Driver technical regulations is unified with points are awarded to the top ten the German touring car series DTM finishers in each race, and the driver duo (Deutsche Tourenwagen Masters). -

Immersion and Worldbuilding in Videogames

Immersion and Worldbuilding in Videogames Omeragić, Edin Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2019 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:664766 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-01 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – prevoditeljski smjer i hrvatskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Edin Omeragić Uranjanje u virtualne svjetove i stvaranje svjetova u video igrama Diplomski rad Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Ljubica Matek Osijek, 2019. Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – prevoditeljski smjer i hrvatskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Edin Omeragić Uranjanje u virtualne svjetove i stvaranje svjetova u video igrama Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Ljubica Matek Osijek, 2019. University of J.J. Strossmayer in Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Study Programme: -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Imagine Dragons – Smoke + Mirrors (Fan Pack) • Emile Haynie – We Fall • Misterwives – Our Own Ho

• Imagine Dragons – Smoke + Mirrors (Fan Pack) • Emile Haynie – We Fall • MisterWives – Our Own House New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI15-07 UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 *Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: SHANIA TWAIN // STILL THE ONE: Live From Vegas (BLU-RAY) Cat. #: EVB335029 Price Code: BC Order Due: February 5, 2015 Release Date: March 3, 2015 File: Pop Genre Code: 33 Box Lot: 25 8 01213 35029 2 Artist/Title: SHANIA TWAIN // STILL THE ONE: Live From Vegas (DVD) Cat. #: EV307009 Price Code: KK 8 01213 07009 1 Synopsis The original queen of crossover country-pop and the world’s best-selling female country artist of all time, Shania Twain, stars in her spectacular show “Shania: Still The One”. This ground-breaking residency show was filmed live at The Colosseum at Caesars Palace, Las Vegas where it began its run on December 1st, 2012. “Shania: Still The One” was created by Shania Twain and directed by Raj Kapoor. It takes the audience on a powerful journey through Shania’s biggest hits, country favourites and beloved crossover songs. Glamorous costumes, a 13-piece live band, backing singers and dancers are combined with stunning visuals and live horses to create the ultimate Las Vegas entertainment and to prove that Shania Twain is undoubtedly Still The One! Bonus Features Backstage Pass – an hour long documentary telling the story of the creation and staging of this amazing live show. Key Selling Points • Filmed in high definition and simultaneously released on Blu-ray. -

Ian Anderson Jonathan Barnbrook Jorge Silva Pedro Falcão Sagmeister & Walsh Curator Guta Moura Guedes

Primeira Pedra First Stone Ian Anderson Jonathan Barnbrook Jorge Silva Pedro Falcão Sagmeister & Walsh Curator Guta Moura Guedes La Triennale di Milano Viale Alemagna 6, 20121 Milano, Italy www.primeirapedra.com 30 March—2 April · 10:30—20:30 4 April · 10:30—00:00 5—9 April · 10:30—22:00 IN PARTNERSHIP COFINANCED BY WITH THE COLLABORATION OF WITH THE HIGH PATRONAGE OF HIS EXCELLENCY THE PRESIDENT OF THE PORTUGUESE REPUBLIC, MARCELO REBELO DE SOUSA The briefing called for a strong emphasis on creativity and innovation, Still Motion Milan to create singular ways of working with stone through graphic design. Primeira Pedra / This field of design has rarely been used in contemporary approaches This exhibition presents a series of original pieces designed by five to stone, having been intensely applied in the past, in structures Credits international graphic design studios, produced using Portuguese stone. such as great monuments and urban, public and private spaces, First Stone Assimagra Still Motion incorporates work by the English designers Ian Anderson both western and oriental. Project Coordination Miguel Goulão, Célia Marques, and Jonathan Barnbrook, the New-York based studio headed by First Stone is an international experimental research programme Daniel Rebelo Austrian designer Stefan Sagmeister and the American Jessica Walsh, Faced with this challenge, the New York based duo Sagmeister & Walsh, exploring the potential of Portuguese Stone, focussing on its uses, Valorpedra and the Portuguese designers Pedro Falcão and Jorge Silva, who have produced communication projects with limitless creativity material properties and distinctive characteristics. The programme Tânia Peças, Nelson Cristo (Technical Consultant) both with studios in Lisbon.