Paradise Saved

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experiences, Challenges and Lessons Learnt in Papua New Guinea

Practice BMJ Glob Health: first published as 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003747 on 3 December 2020. Downloaded from Mortality surveillance and verbal autopsy strategies: experiences, challenges and lessons learnt in Papua New Guinea 1 1 2 3 4 John D Hart , Viola Kwa, Paison Dakulala, Paulus Ripa, Dale Frank, 5 6 7 1 Theresa Lei, Ninkama Moiya, William Lagani, Tim Adair , Deirdre McLaughlin,1 Ian D Riley,1 Alan D Lopez1 To cite: Hart JD, Kwa V, ABSTRACT Summary box Dakulala P, et al. Mortality Full notification of deaths and compilation of good quality surveillance and verbal cause of death data are core, sequential and essential ► Mortality surveillance as part of government pro- autopsy strategies: components of a functional civil registration and vital experiences, challenges and grammes has been successfully introduced in three statistics (CRVS) system. In collaboration with the lessons learnt in Papua New provinces in Papua New Guinea: (Milne Bay, West Government of Papua New Guinea (PNG), trial mortality Guinea. BMJ Global Health New Britain and Western Highlands). surveillance activities were established at sites in Alotau 2020;5:e003747. doi:10.1136/ ► Successful notification and verbal autopsy (VA) District in Milne Bay Province, Tambul- Nebilyer District in bmjgh-2020-003747 strategies require planning at the local level and Western Highlands Province and Talasea District in West selection of appropriate notification agents and VA New Britain Province. Handling editor Soumitra S interviewers, in particular that they have positions of Provincial Health Authorities trialled strategies to improve Bhuyan trust in the community. completeness of death notification and implement an Additional material is ► It is essential that notification and VA data collec- ► automated verbal autopsy methodology, including use of published online only. -

Civil Aviation Development Investment Program (Tranche 3)

Resettlement Due Diligence Reports Project Number: 43141-044 June 2016 PNG: Multitranche Financing Facility - Civil Aviation Development Investment Program (Tranche 3) Prepared by National Airports Corporation for the Asian Development Bank. This resettlement due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Table of Contents B. Resettlement Due Diligence Report 1. Madang Airport Due Diligence Report 2. Mendi Airport Due Diligence Report 3. Momote Airport Due Diligence Report 4. Mt. Hagen Due Diligence Report 5. Vanimo Airport Due Diligence Report 6. Wewak Airport Due Diligence Report 4. Madang Airport Due Diligence Report. I. OUTLINE FOR MADANG AIRPORT DUE DILIGENCE REPORT 1. The is a Due Diligent Report (DDR) that reviews the Pavement Strengthening Upgrading, & Associated Works proposed for the Madang Airport in Madang Province (MP). It presents social safeguard aspects/social impacts assessment of the proposed works and mitigation measures. II. BACKGROUND INFORMATION 2. Madang Airport is situated at 5° 12 30 S, 145° 47 0 E in Madang and is about 5km from Madang Town, Provincial Headquarters of Madang Province where banks, post office, business houses, hotels and guest houses are located. -

Health&Medicalinfoupdate8/10/2017 Page 1 HEALTH and MEDICAL

HEALTH AND MEDICAL INFORMATION The American Embassy assumes no responsibility for the professional ability or integrity of the persons, centers, or hospitals appearing on this list. The names of doctors are listed in alphabetical, specialty and regional order. The order in which this information appears has no other significance. Routine care is generally available from general practitioners or family practice professionals. Care from specialists is by referral only, which means you first visit the general practitioner before seeing the specialist. Most specialists have private offices (called “surgeries” or “clinic”), as well as consulting and treatment rooms located in Medical Centers attached to the main teaching hospitals. Residential areas are served by a large number of general practitioners who can take care of most general illnesses The U.S Government assumes no responsibility for payment of medical expenses for private individuals. The Social Security Medicare Program does not provide coverage for hospital or medical outside the U.S.A. For further information please see our information sheet entitled “Medical Information for American Traveling Abroad.” IMPORTANT EMERGENCY NUMBERS AMBULANCE/EMERGENCY SERVICES (National Capital District only) Police: 112 / (675) 324-4200 Fire: 110 St John Ambulance: 111 Life-line: 326-0011 / 326-1680 Mental Health Services: 301-3694 HIV/AIDS info: 323-6161 MEDEVAC Niugini Air Rescue Tel (675) 323-2033 Fax (675) 323-5244 Airport (675) 323-4700; A/H Mobile (675) 683-0305 Toll free: 0561293722468 - 24hrs Medevac Pacific Services: Tel (675) 323-5626; 325-6633 Mobile (675) 683-8767 PNG Wide Toll free: 1801 911 / 76835227 – 24hrs Health&MedicalInfoupdate8/10/2017 Page 1 AMR Air Ambulance 8001 South InterPort Blvd Ste. -

Agricultural Systems of Papua New Guinea Working Paper No

AGRICULTURAL SYSTEMS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA Working Paper No. 6 MILNE BAY PROVINCE TEXT SUMMARIES, MAPS, CODE LISTS AND VILLAGE IDENTIFICATION R.L. Hide, R.M. Bourke, B.J. Allen, T. Betitis, D. Fritsch, R. Grau, L. Kurika, E. Lowes, D.K. Mitchell, S.S. Rangai, M. Sakiasi, G. Sem and B. Suma Department of Human Geography, The Australian National University, ACT 0200, Australia REVISED and REPRINTED 2002 Correct Citation: Hide, R.L., Bourke, R.M., Allen, B.J., Betitis, T., Fritsch, D., Grau, R., Kurika, L., Lowes, E., Mitchell, D.K., Rangai, S.S., Sakiasi, M., Sem, G. and Suma,B. (2002). Milne Bay Province: Text Summaries, Maps, Code Lists and Village Identification. Agricultural Systems of Papua New Guinea Working Paper No. 6. Land Management Group, Department of Human Geography, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University, Canberra. Revised edition. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry: Milne Bay Province: text summaries, maps, code lists and village identification. Rev. ed. ISBN 0 9579381 6 0 1. Agricultural systems – Papua New Guinea – Milne Bay Province. 2. Agricultural geography – Papua New Guinea – Milne Bay Province. 3. Agricultural mapping – Papua New Guinea – Milne Bay Province. I. Hide, Robin Lamond. II. Australian National University. Land Management Group. (Series: Agricultural systems of Papua New Guinea working paper; no. 6). 630.99541 Cover Photograph: The late Gore Gabriel clearing undergrowth from a pandanus nut grove in the Sinasina area, Simbu Province (R.L. -

Milne Bay Expedition Trekking and Kayaking 2019

Culture & History Trekking & Kayaking Stand Up Paddle Boarding Kavieng Rabaul Trekking Adventures Madang PapuaMt WilhelmNew Guinea Mt Hagen Goroka Lae ABOUT PAPUA NEW GUINEA Salamaua Papua New Guinea occupies the eastern half of the rugged tropical island of New Guinea (which it shares with the Indonesian territory of Irian Jaya) as well as numerous smaller islands and atolls in the Pacific. The central part of the island rises into a wide ridge of mountains known as the Highlands, a terri- Kokoda tory that is so densely forested and topographically forbidding that the island’s local people remained Tufi isolated from each other for millennia. The coastline Owers’ Crn is liberally endowed with spectacular coral reefs, giv- Port Moresby ing the country an international reputation for scuba diving. The smaller island groups of Papua New Alotau Guinea include the Bismarck Archipelago, New Brit- ain, New Ireland and the North Solomon’s. Some of these islands are volcanic, with dramatic mountain ranges, and all are relatively undeveloped. Nearly 85 percent of the main island is carpeted with tropical rain forest, containing vegetation that has its origins from Asia and Australia. The country is also home to an impressive variety of exotic birds, in- cluding virtually all of the known species of Bird’s of Paradise, and it is blessed with more kinds of orchids than any other country. For centuries, the South Pa- cific has been luring the traveller who searched for excitement, beauty and tranquillity. The exploits of sailors to the South Pacific have been told and re- told, but in telling, there is one large country which is not mentioned, Papua New Guinea. -

PNG: Building Resilience to Climate Change in Papua New Guinea

Environmental Assessment and Review Framework September 2015 PNG: Building Resilience to Climate Change in Papua New Guinea This environmental assessment and review framework is a document of the borrower/recipient. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Project information, including draft and final documents, will be made available for public review and comment as per ADB Public Communications Policy 2011. The environmental assessment and review framework will be uploaded to ADB website and will be disclosed locally. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................. ii 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 1 A. BACKGROUND ..................................................................................................................................... -

A Trial Separation: Australia and the Decolonisation of Papua New Guinea

A TRIAL SEPARATION A TRIAL SEPARATION Australia and the Decolonisation of Papua New Guinea DONALD DENOON Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Denoon, Donald. Title: A trial separation : Australia and the decolonisation of Papua New Guinea / Donald Denoon. ISBN: 9781921862915 (pbk.) 9781921862922 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Decolonization--Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea--Politics and government Dewey Number: 325.953 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover: Barbara Brash, Red Bird of Paradise, Print Printed by Griffin Press First published by Pandanus Books, 2005 This edition © 2012 ANU E Press For the many students who taught me so much about Papua New Guinea, and for Christina Goode, John Greenwell and Alan Kerr, who explained so much about Australia. vi ST MATTHIAS MANUS GROUP MANUS I BIS MARCK ARCH IPEL AGO WEST SEPIK Wewak EAST SSEPIKEPIK River Sepik MADANG NEW GUINEA ENGA W.H. Mt Hagen M Goroka a INDONESIA S.H. rk ha E.H. m R Lae WEST MOROBEMOR PAPUA NEW BRITAIN WESTERN F ly Ri ver GULF NORTHERNOR N Gulf of Papua Daru Port Torres Strait Moresby CENTRAL AUSTRALIA CORAL SEA Map 1: The provinces of Papua New Guinea vii 0 300 kilometres 0 150 miles NEW IRELAND PACIFIC OCEAN NEW IRELAND Rabaul BOUGAINVILLE I EAST Arawa NEW BRITAIN Panguna SOLOMON SEA SOLOMON ISLANDS D ’EN N TR E C A S T E A U X MILNE BAY I S LOUISIADE ARCHIPELAGO © Carto ANU 05-031 viii W ALLAC E'S LINE SUNDALAND WALLACEA SAHULLAND 0 500 km © Carto ANU 05-031b Map 2: The prehistoric continent of Sahul consisted of the continent of Australia and the islands of New Guinea and Tasmania. -

Northern and Milne Bay Mission, South Pacific Division

Northern and Milne Bay Mission headquarters, Papua New Guinea. Photo courtesy of Barry Oliver. Northern and Milne Bay Mission, South Pacific Division BARRY OLIVER Barry Oliver, Ph.D., retired in 2015 as president of the South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists, Sydney, Australia. An Australian by birth Oliver has served the Church as a pastor, evangelist, college teacher, and administrator. In retirement, he is a conjoint associate professor at Avondale College of Higher Education. He has authored over 106 significant publications and 192 magazine articles. He is married to Julie with three adult sons and three grandchildren. The Northern and Milne Bay Mission (N&MBM) is the Seventh-day Adventist Church administrative entity for the Northern and Milne Bay areas of Papua New Guinea.1 The Territory and Statistics of the Northern and Milne Bay Mission The territory of the N&MBM is the “Milne Bay and Northern Provinces of Papua New Guinea.”2 It is a part of and responsible to the Papua New Guinea Union Mission, Lae, Morobe Province, Papua New Guinea. The Papua New Guinea Union Mission comprises the Seventh-day Adventist Church entities in the country of Papua New Guinea. There are nine local missions and one local conference in the union. They are the Central Papuan Conference, the Bougainville Mission, the New Britain New Ireland Mission, the Northern and Milne Bay Mission, Morobe Mission, Madang Manus Mission, Sepik Mission, Eastern Highlands Simbu Mission, Western Highlands Mission and South West Papuan Mission. The administrative office of N&MBM is located at Killerton Road, Popondetta 241, Papua New Guinea. -

PDF Download

Journal of the Ocean Science Foundation 2014, Volume 11 A new species of damselfish (Chromis: Pomacentridae) from Papua New Guinea GERALD R. ALLEN Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC Perth, Western Australia 6986, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] MARK V. ERDMANN Conservation International, Jl. Dr. Muwardi No. 17, Renon, Denpasar, Bali 80235, Indonesia California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, CA 94118 USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A new species of pomacentrid fish,Chromis howsoni, is described from 24 specimens, 30.7–56.2 mm SL, collected in 17–20 m at Milne Bay and Oro Provinces, Papua New Guinea. Diagnostic features include usual counts of XII,12 dorsal rays; II,12 anal rays; 15–16 pectoral rays; 2 spiniform caudal rays; 13 tubed lateral-line scales; body depth 1.6–1.8 (usually 1.7) in SL. The new taxon is closely allied to Chromis amboinensis, differing mainly on the basis of colour pattern and a slightly shorter caudal peduncle (length 2.3–2.9 versus 1.8–2.3 in head length). It is distinguished by an overall yellowish brown colour, yellow pelvic fins, and yellow areas posteriorly on the dorsal and anal fins. In contrast, C. amboinensis is overall brownish grey with white pelvic fins, and whitish or translucent areas posteriorly on the dorsal and anal fins. The two species occur sympatrically in Papua New Guinea, but exhibit marked habitat partitioning, with C. howsoni the only species present in sheltered coastal inlets and C. amboinensis vastly outnumbering C. -

A Rapid Biodiversity Survey of Papua New Guinea’S Manus and Mussau Islands

A Rapid Biodiversity Survey of Papua New Guinea’s Manus and Mussau Islands edited by Nathan Whitmore Published by: Wildlife Conservation Society Papua New Guinea Program PO BOX 277, Goroka, Eastern Highlands Province PAPUA NEW GUINEA Tel: +675-532-3494 www.wcs.org Editor: Nathan Whitmore. Authors: Ken P. Aplin, Arison Arihafa, Kyle N. Armstrong, Richard Cuthbert, Chris J. Müller, Junior Novera, Stephen J. Richards, William Tamarua, Günther Theischinger, Fanie Venter, and Nathan Whitmore. The Wildlife Conservation Society is a private, not-for-profit organisation exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Inland Revenue Code. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Wildlife Conservation Society, the Criticial Ecosystems Partnership Fund, nor the Papua New Guinean Department of Environment or Conservation. Suggested citation: Whitmore N. (editor) 2015. A rapid biodiversity survey of Papua New Guinea’s Manus and Mussau Islands. Wildlife Conservation Society Papua New Guinea Program. Goroka, PNG. ISBN: 978-0-9943203-1-5 Front cover Image: Fanie Venter: cliffs of Mussau. ©2015 Wildlife Conservation Society A rapid biodiversity survey of Papua New Guinea’s Manus and Mussau Islands. Edited by Nathan Whitmore Table of Contents Participants i Acknowledgements iii Organisational profiles iv Letter of support v Foreword vi Executive summary vii Introduction 1 Chapters 1: Plants of Mussau Island 4 2: Butterflies of Mussau Island (Lepidoptera: Rhopalocera) -

Coastal Fishery Management and Development Projects in Papua

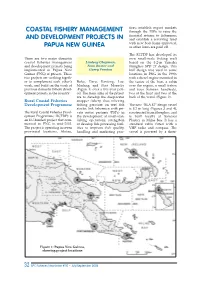

tices; establish export markets COASTAL FISHERY MANAGEMENT through the PSPs to raise the financial returns to fishermen; AND DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS IN and establish a revolving fund with new boat loans approved, PAPUA NEW GUINEA as other loans are paid off. The RCFDP has developed its There are two major domestic own small-scale fishing craft coastal fisheries management Lindsay Chapman, based on the 8.2-m Yamaha and development projects being Sean Baxter and fibreglass SPD 27 design. This implemented in Papua New Garry Preston hull design was used in some Guinea (PNG) at present. These locations in PNG in the 1990s two projects are working togeth- with a diesel engine mounted in er to complement each other’s Buka, Daru, Kavieng, Lae, the centre of the boat, a cabin work, and build on the work of Madang and Port Moresby over the engine, a small icebox previous domestic fishery devel- (Figure 1) over a five-year peri- and four Samoan handreels, opment projects in the country. od. The main aims of the project two at the front and two at the are to develop the deep-water back of the vessel (Figure 2). Rural Coastal Fisheries snapper fishery, thus relieving Development Programme fishing pressure on reef fish The new “ELA 82” design vessel stocks; link fishermen with pri- is 8.2 m long (Figures 3 and 4), The Rural Coastal Fisheries Devel- vate sector partners (PSPs) in constructed from fibreglass, and opment Programme (RCFDP) is the development of small-scale is built locally at Samarai an EU-funded project that com- fishing operations; strengthen Plastics in Milne Bay. -

Social Assessment – Indigenous Peoples

Social assessment – indigenous peoples Empowering the people of Pobuma to design conservation actions on Manus Island Papua New Guinea Indigenous Peoples in the project area Manus Province Manus is the smallest province in Papua New Guinea in terms of both the population size and land mass. During the 2000 National Census, Manus had a total population of 43,387 people (National Census 2000). Of the total population of 43,387 the majority of people, 83 percent live in the rural areas. The average annual population growth in Papua New Guinea is 2.8%, which places a projected population of Manus Province at about 62,000 people. Manus Province has a land area of 2,149.1 square kilometres with the main island of Manus covered with tropical rainforests and a vast sea area of 274,243.6 square kilometres. The island of Manus is situated about 2.9 degrees south of equator and 147 degrees east. Manus is located ideally within the Coral Triangle countries and has diverse biodiversity hotspots which are included amongst those found in the East Melanesia Islands region. The proposed rubber estate is owned by the Powai people and will be about 100 hectares in size. This will be right next to the mountain ranges within Central Manus where Mt Dremsel is located. Mt Dremsel is the highest peak in Manus and is home to high biodiversity. This rubber estate development is expected to take place before end of 2016. The rubber estate project will be a joint venture between the Powai people from Jekal, Pelipowai, Peli-Patu, and Kupano communities and a Malaysian logging company called Maxland.