The Economic Motives for Foot-Binding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Missionary Journal, “Chinese Character” This Article Was

1. Missionary Journal, “Chinese Character” This article was published in a Protestant missionary journal, based in Canton, that operated from 1832 until 1851. Its readership included both the foreigners living in Canton and home religious communities in Britain and the United States. It is worthwhile noting that the title of the article places the author in the position of knowledgeable observer, thereby rendering his comments both “factual” and honest. The author maintains a sympathetic attitude towards Chinese women, citing their beauty and charm, yet paints them as victims of insensitive males and an oppressive culture, presuming an invisible sorrow shared by all women in China. Confucianism is named as the primary offender, and Christian conversion the sole savior. One may presume that this portrayal of delicate Chinese women as victims of brutish Confucianism helped to excite enthusiasm for the missionary cause in China both at home and abroad. Source: Lay, G. Tradescant. “Remarks on Chinese Character and Customs.” Chinese Repository 12 (1843): 139-142. No apology can or ought to be made in the behalf of the unfeeling practice of spoiling the feet of the female. It had its origin solely in pride, which after the familiar adage, is said to feel no pain. It is deemed, however, such an essential among the elements of feminine beauty, that nothing save the sublimer considerations of Christianity will ever wean them from the infatuation. The more reduced this useful member is, the more graceful and becoming it is thought to be. When gentlemen are reciting the unparalleled charms of Súchau ladies they seldom forget to mention the extreme smallness of the foot, as that which renders them complete, and lays the topstone upon all the rest of their personal accomplishments. -

Female Body Modification Through Physical Manipulation: a Comparison of Foot-Binding and Corsetry

Female Body Modification through Physical Manipulation: A Comparison of Foot-Binding and Corsetry Hannah Conroy [email protected] History Department April 7 th , 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank Aunt Bonnie’s Books for the donation of A History of Fashion in the 20th Century , by Gertrud Lehnert and Vintage Clothing 1880 - 1980 , by Maryanne Dolan. I walked in and asked about a very specific kind of book and you just handed me the only two you had, free of charge. You have a customer for life. One big “thank you!” to my mother, Suzie Conroy, for her continued support and hard work during my attendance at Carroll College; without her, I would not have attended Carroll. Hey mom, we made it! I would also like to thank the entire staff of the Carroll College Corette Library, especially Kathy Martin for getting every book I ever asked for. Thank you to both of my readers, Dr. Kay Satre and Dr. Jamie Dolan. You are wonderful women and I really appreciate your feedback. Last, but not least, thanks to Dr. Jeanette Fregulia for her support and patience with me as I wound my way through this education. Your guidance has been invaluable to me during each semester. ABSTRACT Over the past fifty years, with the continuing contributions of many Gender History scholars, historians are now presented with an opportunity to explore an often over- looked area within the physical manipulation of women’s bodies. There are a variety of means by which the female form is shaped by the cultural and societal norms, including the pressures to look young and beautiful. -

Footbinding, Sexuality and Transnational Feminism Zhang Yuan

Footbinding, Sexuality and Transnational Feminism Zhang Yuan Footbinding, Sexuality and Transnational Feminism Zhang Yuan 3204235 June, 2009 Footbinding, Sexuality and Transnational Feminism Zhang Yuan Contents Introduction................................................................................ 1 I Footbinding in General........................................................... 2 II Footbinding under Western and Eastern Eyes.................. 12 (1) Western Interpretations of Footbinding ..................... 12 (2) Eastern Interpretations of Footbinding ...................... 16 III Footbinding and Sexuality................................................. 20 IV Can bound-feet women speak?.......................................... 25 V Transnational Feminism...................................................... 37 VI Conclusion........................................................................... 46 References and Bibliography.................................................. 49 Footbinding, Sexuality and Transnational Feminism Zhang Yuan Introduction Footbinding was a Chinese custom where women bound their feet with cloth to make them smaller. As a special culture, it has spread its influence deeply into various fields in Chinese social life (both female and male) during the past centuries, such as music, dance, painting, literature, costume, and so on. For instance, footbinding “had the regrettable consequence that it put a stop to the great old Chinese art of dancing” (Van Gulik, 1961) and thereby perhaps pushed females -

A FEMINIST SCIENCE STUDIES CRITIQUE of ANTI-FGM DISCOURSE Wairimé Ngaréiya Njambi Dissertation Submitted To

COLONIZING BODIES: A FEMINIST SCIENCE STUDIES CRITIQUE OF ANTI-FGM DISCOURSE Wairimé Ngaréiya Njambi Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY STUDIES APPROVED: Gary Downey, Chair Charles M. Good Ann Kilkelly Ann La Berge Timothy Luke September 8, 2000 Blacksburg, Virginia Copyright 2001, Wairimé Ngaréiya Njambi COLONIZING BODIES: A FEMINIST SCIENCE STUDIES CRITIQUE OF ANTI-FGM DISCOURSE by Wairimé Ngaréiya Njambi Gary Downey, Chair Science and Technology Studies (ABSTRACT) The contentious topic of female circumcision brings together medical science, women’s health activism, and national and international policy-making in pursuit of the common goal of protecting female bodies from harm. To date, most criticisms of female circumcision, practiced mainly in parts of Africa and Southwest Asia, have revolved around the dual issues of control of female bodies by a male-dominated social order and the health impacts surrounding the psychology of female sexuality and the functioning of female sex organs. As such, the recently-evolved campaign to eradicate female circumcision, alternatively termed “Female Genital Mutilation” (FGM), has formed into a discourse intertwining the politics of feminist activism with scientific knowledge and medical knowledge of the female body and sexuality. This project focuses on the ways in which this discourse constructs particular definitions of bodies and sexuality in a quest to generalize the practices of female circumcision as “harmful” and therefore dangerous. Given that the discourse aimed at eradicating practices of female circumcision, referred to in this study as “anti-FGM discourse,” focuses mostly on harm done to women’s bodies, this project critiques the assumption of universalism regarding female bodies and sexuality that is explicitly/implicitly embedded in such discourse. -

Violence Against Women in Kenya an Analysis of Law, Policy and Institutions

Violence Against Women in Kenya An Analysis of Law, Policy and Institutions Dr Patricia Kameri-Mbote IELRC WORKING PAPER 2000 - 1 This paper can be downloaded in PDF format from IELRC’s website at http://www.ielrc.org/content/w0001.pdf International Environmental Law Research Centre International Environmental House Chemin de Balexert 7 & 9 1219 Châtelaine Geneva, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Table of Content I. Introduction 1 A. Typology of violence against women 1 B. Causes of Violence 1 C. Consequences of Violence against Women 3 D. Scope of study 3 II. Contextual Framework of Analysis 4 A. A General Note 4 B. Historical Background 4 III. The Legal Framework 5 A. International Legal Standards on Violence Against Women 5 B. National legal provisions protecting women from violence 9 IV. Extra-Legal Forms of Violence 19 A. Wife battering 19 B. Witch burning 20 C. Female Genital Mutilation. 21 V. Institutional Structures 22 A. Institutionalised violence against women 22 B. Courts 23 C. Elders 24 VI. Gaps in the National Laws 24 VII. Recent Interventions 25 A. Criminal law ammendment bill, 2000 25 B. Domestic Violence (Family Protection) Bill, 1999 26 C. Affirmative Action Bill 26 D. National Council for Gender Development Bill, 1999 26 VIII. Conclusion and Recommendations 26 A. International Human Rights Instruments on Violence against Women 26 B. The Constitution: 27 C The Penal Code 27 D. General Law Reform 28 D. Policies 28 ii I. Introduction The issue of violence against women has only recently become a subject of specific scientific inquiry. Previously, violations of women were dealt with within the general purview of law dealing with assault. -

Proposal Penelitian

SEMIOTIKA Volume 20 Nomor 1, Januari 2019 Halaman 14—25 URL: https://jurnal.unej.ac.id/index.php/SEMIOTIKA/index E-ISSN: 2599-3429 P-ISSN: 1411-5948 THE REPRESENTATION OF WOMAN’S OPPRESSION IN LISA SEE’S SNOW FLOWER AND THE SECRET FAN REPRESENTASI PENINDASAN PEREMPUAN DALAM NOVEL SNOW FLOWER AND THE SECRET FAN KARYA LISA SEE Azara Nafia Irmadani1, Supiastutik2*, Irana Astutiningsih3 1Alumni of Faculty of Humanities, Universitas Jember 2,3Faculty of Humanities, Universitas Jember *Corresponding Author: supiastutik.sastra@ unej.ac.id Informasi Artikel: Dikirim: 19/8/2018; Direvisi: 28/10/2019; Diterima: 18/11/2018 Abstract Snow Flower and The Secret Fan is one type of fiction written by Lisa See in 2005. Snow Flower and The Secret Fan tells about the lives of Chinese women in the nineteenth century where women's position was subjugated. In that era, there was a tradition that required women to tie their feet when they were young then caused them to endure unbearable pain because of a foot-binding. By wrapping their feet tightly, they can get married and improve their social status and bring them to a better life. Foot-binding is a sexually pleasure for men to achieve sexual satisfaction. In addition, in that era women were not permitted to get education like men. This problem was the impact of the Patriarchal culture. In the Patriarchal culture, there is a Confucian teaching that is used as a way of life for Chinese people. The teaching requires women to obey men: father, husband, and later their sons. Therefore, Chinese women live as a second-class. -

Alison Lapper Pregnant

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives University of Bergen Institute of Linguistic, Literary, and Aesthetic Studies KUN350 Master thesis in art history Spring 2014 A Contemporary Body in Classical Guise Representation of disability in classical form and contemporary beauty norm in Alison Lapper Pregnant. Elisabeth Tveite 1 List of Contents Foreword 5 Introduction 6 Gullbarbie 6 Fragmented bodies 8 My research question 9 My thesis 11 1: The fragmented body in contemporary art 13 In dialog with Quinn 14 The Complete Marbles: classical material, new subject 15 Alison Lapper Pregnant 17 Fragmented gods and goddesses 18 Torso di Ikaro and Torso Alato 19 Female [pregnant] nude 21 Miss Landmine 25 2: Young British Artists: fast food art or mirroring society? 27 Contexts and theories 27 The postmodern condition 27 Postmodernists 29 Young British Artists 31 Freeze 32 Artist, curator and celebrity 34 Contemporary Beauty 36 Beauty versus nonbeauty 38 Disability studies 39 An uncanny feeling 41 2 Unheimlich 42 Abject Art 44 A dirty protest 45 From beauty to abject, from abject to beauty 47 3: The Art of the Body 48 Classicisms 48 The ideal man and woman 48 The male gaze 49 Hubris 51 Nudity, pose and naturalistic appearance 52 Reception Theory 54 Venus de Milo and Belvedere Torso: fragmented ideals 55 Disability in Greek and Roman society 56 Belvedere Torso 57 Venus de Milo 60 Wholeness and beauty in Neoclassical art 62 Chromophobia 64 Victorious Venus 65 -

Prostitution in Shanghai

chapter 22 Prostitution in Shanghai Sue Gronewold Introduction Shanghai and Prostitution This chapter traces the history of sex work in Shanghai over four centuries and views the history of prostitution in Shanghai as one part of the story of a changing city in a radically changing China. Of the countries included in this project, China is of particular interest since it represents a case in which pros- titution was historically tolerated and regulated legally and socially by a highly centralized state1 which went through dramatic transformations in the twenti- eth century, with policies on prostitution shifting just as extremely. * In the footnotes, Chinese names are rendered in the western fashion with personal name first and family name last but in the text the traditional Chinese style is maintained. 1 There has been interest in and concern about prostitution throughout Chinese history, and it has long been a subject of literature, drama, and poetry as well as law, with wide-ranging sources, especially since the boom in printing in the late sixteenth century and subsequent rise of vernacular fiction that allowed for much more nuanced and full descriptions of gender models and sexual mores. Giovanni Vitiello, Libertine’s Friend: Homosexuality and Masculin- ity in Late Imperial China (Chicago, 2011), pp. 4–5. Another category mined by social histori- ans has been unofficial histories (yeshi) which were touted by late Qing reformers as the most useful way to educate the public “to save the nation with fiction.” Quoted in Madeleine Yue Dong, “Unofficial History and Gender Boundary Crossing in the Early Chinese Republic: Shen Peizhen and Xiaofengxian”, in Beata Goodman and Wendy Larson (eds), Gender in Motion: Divisions of Labor and Cultural Change in Late Imperial China (Lanham, 2005), pp. -

The Economic Motives for Foot-Bindingversion

∗ The Economic Motives for Foot-binding † ‡ Xinyu FAN and Lingwei WU Abstract What are the origins of gender-biased social norms? This paper presents a unified theory to understand foot-binding – a long-standing custom that reshaped the feet of girls in historical China – and investigates its adoption dynamics driven by a gender-asymmetric mobility system (the Civil Examination System). The exam system marked the transition from heredity aris- tocracy to meritocracy, which generated a more heterogeneous composition of men compared to women, triggering intensive competition among women in the marriage market. Embodying both aesthetic and moral values, foot-binding was gradually adopted by women as a social lad- der, first by the upper class and later by the lower class. However, since foot-binding impedes non-sedentary labor but not sedentary labor, its adoption in the lower class exhibited distinc- tive regional variation: it was highly prevalent in regions where women specialized in household handicraft, and was less popular in regions where women specialized in intensive farming, e.g. rice cultivation. Empirical results with county-level Republican archives on foot-binding are consistent with theoretical predictions. JEL Codes: C78, N35, J16, Z10 ∗Version: December, 2018. We are deeply indebted to Albert Park for his mentoring and guidance, and James Kung for encouragement and support. This work benefited a lot from the comments of Ying Bai, Laurel Bossen, Leah Platt Boustan, Loren Brandt, Shu Cai, Jean-Paul Carvalho, Cornelius Christian, Kim-Sau Chung, Dora Costa, Christian Dippel, Paola Giuliano, Li Han, Walker Hanlon, Jean Hong, Ruixue Jia, James Z. Lee, Siu Fai Leung, Yatang Lin, Elaine Liu, Yang Lu, Travis Ng, Sheilagh Ogilvie, Michael Poyker, Nancy Qian, Xiaoyue Shan, Carol Shiue, Aloysius Siow, Yufeng Sun, Felipe Valencia Caicedo, Sujata Visaria, Jin Wang, Tianyang Xi, Melanie Xue, Jane Zhang and participants in the seminars at UCLA (Econ History Pro-seminar), Bonn, CUHK, HKU, Toronto, and ISQH (Beijing), EHA (Boulder), NEUDC (MIT) and SSHA (Montreal). -

The Chinese Lady and China for the Ladies Race, Gender, and Public Exhibition in Jacksonian America John Haddad

The Chinese Lady and China for the Ladies Race, Gender, and Public Exhibition in Jacksonian America John Haddad John Haddad, “The Chinese Lady and China for the Ladies: Race, area amusements hints at the difference between Moy and Gender, and Public Exhibition in Jacksonian America,” Chinese some of the other popular attractions of Jacksonian America: America: History & Perspectives —The Journal of the Chi- Mr. Maelzell burns Moscow in an improved style. —The eastern nese Historical Society of America (San Francisco: Chinese Magician, Bahad Marchael, astonished crowds by raising and Historical Society of America with UCLA Asian American Studies laying ghosts, and shows himself to be the most expert professor Center, 2011), 5–19. of legerdemain and necromancy that has ever visited the city. — The Chinese lady, Afong Moy, has arrived there from the south— and last, as well as least, there is an exhibition of trained fleas.3 Unlike most acts from this period, Afong Moy did not juggle, INTRODUCTION work with trained animals, or profess to communicate with the dead—yet American audiences did not seem to mind. n 1830, Harriet Low, the niece of a China trader, strolled For they required only that the Chinese Lady be exactly that: through the narrow streets of Canton, China. Though authentically Chinese and a woman of affluence, elegance, Ithis activity may seem routine, she was actually acting and refinement. in bold defiance of a Qing law that forbade the presence of Indeed, Afong Moy’s nationality, gender, and class were Western women in China. Not surprisingly, Low attracted absolutely crucial to her popularity, because without each of a crowd of Cantonese onlookers, most of whom had never these, she would not have possessed the remarkable physi- before seen a White woman. -

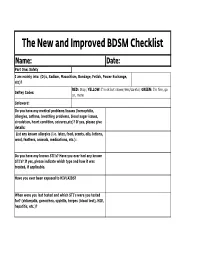

The New and Improved BDSM Checklist

The New and Improved BDSM Checklist Name: Date: Part One: Safety I am mainly into: (D/s, Sadism, Masochism, Bondage, Fetish, Power Exchange, etc)? RED: Stop; YELLOW: I'm ok but slower/less/careful; GREEN: I'm fine, go Saftey Codes: on, more Safeword: Do you have any medical problems/issues (hemophilia, allergies, asthma, breathing problems, blood sugar issues, circulation, heart condition, seizures,etc)? If yes, please give details: List any known allergies (i.e. latex, food, scents, oils, lotions, wool, feathers, animals, medications, etc.): Do you have any known STI's? Have you ever had any known STI's? If yes, please indicate which type and how it was treated, if applicable. Have you ever been exposed to HIV/AIDS? When were you last tested and which STI's were you tested for? (chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, herpes (blood test), HIV, hepatitis, etc.)? Have you received any STI vaccinations (i.e. hepatitis A & B or HPV)? How often do you practice safe sex (always, most of the time, some of the time, never)? Please explain reasons for not doing so. Medications: Have you taken any medication, including Asprin within the last 4-6 hours (Asprin changes your blood's clotting time). Please include a list of all prescription and over the counter medications you are currently taking: Visible brusies, cuts, or marks must be avoided (yes or no)? Please list any no hit zones, if any: Do you have any phobias or fears that the Dom/Domme should be aware of (blood, needles, enclosed areas, etc.)? Do you want aftercare (yes, no, only in certain circumstances, unsure, etc.)? Please explain. -

Conceptualising Psycho-Emotional Aspects of Disablist Discrimination and Impairment

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository Conceptualising psycho-emotional aspects of disablist discrimination and impairment: Towards a psychoanalytically informed disability studies Brian Paul Watermeyer Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Psychology, Stellenbosch University Promotor: Prof. Leslie Swartz December 2009 Declaration By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Signature:……………………….. Date:…………………………….. Copyright © 2009 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii ABSTRACT Since the 1970s, the international disability movement has galvanised around the "social model" of disability, as an adversarial response to traditional, individualising "medical" accounts of disablement. The model foregrounds "disablist ideology", identifying systematic exclusion and discrimination as central mediators of disabled life. Latterly, feminist authors within disability studies have problematised the "arid" materialist orientation of the social model, for its eschewing of personal and psychological aspects of disability, and poor theorising of embodiment. Social model orthodoxy construes the psychological as epiphenomenal, diversionary, and potentially misappropriated