In the Presence of Beauty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hudson River School

Hudson River School 1796 1800 1801 1805 1810 Asher 1811 Brown 1815 1816 Durand 1820 Thomas 1820 1821 Cole 1823 1823 1825 John 1826 Frederick 1827 1827 1827 1830 Kensett 1830 Robert 1835 John S Sanford William Duncanson David 1840 Gifford Casilear Johnson Jasper 1845 1848 Francis Frederic Thomas 1850 Cropsey Edwin Moran Worthington Church Thomas 1855 Whittredge Hill 1860 Albert 1865 Bierstadt 1870 1872 1875 1872 1880 1880 1885 1886 1910 1890 1893 1908 1900 1900 1908 1908 1902 Compiled by Malcolm A Moore Ph.D. IM Rocky Cliff (1857) Reynolds House Museum of American Art The Beeches (1845) Metropolitan Museum of Art Asher Brown Durand (1796-1886) Kindred Spirits (1862) Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art The Fountain of Vaucluse (1841) Dallas Museum of Art View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm - the Oxbow. (1836) Metropolitan Museum of Art Thomas Cole (1801-48) Distant View of Niagara Falls (1836) Art Institute of Chicago Temple of Segesta with the Artist Sketching (1836) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston John William Casilear (1811-1893) John Frederick Kensett (1816-72) Lake George (1857) Metropolitan Museum of Art View of the Beach at Beverly, Massachusetts (1869) Santa Barbara Museum of Art David Johnson (1827-1908) Natural Bridge, Virginia (1860) Reynolda House Museum of American Art Lake George (1869) Metropolitan Museum of Art Worthington Whittredge (1820-1910) Jasper Francis Cropsey (1823-1900) Indian Encampment (1870-76) Terra Foundation for American Art Starrucca Viaduct, Pennsylvania (1865) Toledo Museum of Art Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823-1880) Robert S Duncanson (1821-1902) Whiteface Mountain from Lake Placid (1866) Smithsonian American Art Museum On the St. -

Supplementary Information For

1 2 Supplementary Information for 3 Dissecting landscape art history with information theory 4 Byunghwee Lee, Min Kyung Seo, Daniel Kim, In-seob Shin, Maximilian Schich, Hawoong Jeong, Seung Kee Han 5 Hawoong Jeong 6 E-mail:[email protected] 7 Seung Kee Han 8 E-mail:[email protected] 9 This PDF file includes: 10 Supplementary text 11 Figs. S1 to S20 12 Tables S1 to S2 13 References for SI reference citations www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.2011927117 Byunghwee Lee, Min Kyung Seo, Daniel Kim, In-seob Shin, Maximilian Schich, Hawoong Jeong, Seung Kee Han 1 of 28 14 Supporting Information Text 15 I. Datasets 16 A. Data curation. Digital scans of landscape paintings were collected from the two major online sources: Wiki Art (WA) (1) 17 and the Web Gallery of Art (WGA) (2). For our purpose, we collected 12,431 landscape paintings by 1,071 artists assigned to 18 61 nationalities from WA, and 3,610 landscape paintings by 816 artists assigned with 20 nationalities from WGA. While the 19 overall number of paintings from WGA is relatively smaller than from WA, the WGA dataset has a larger volume of paintings 20 produced before 1800 CE. Therefore, we utilize both datasets in a complementary way. 21 As same paintings can be included in both datasets, we carefully constructed a unified dataset by filtering out the duplicate 22 paintings from both datasets by using meta-information of paintings (title, painter, completion date, etc.) to construct a unified 23 set of painting images. The filtering process is as follows. -

Durand Release

COMMUNICATIONS DIVISION VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS 200 N. Boulevard I Richmond, Virginia 23220 www.VMFA.museum/pressroom FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Dec. 13, 2018 Asher B. Durand’s Progress, Most Valuable Gift of a Single Work of Art in VMFA’s History, Enters Museum Collection Gift marks first time the painting has been in public domain since its creation in 1853 Richmond, VA––The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts recently received the generous anonymous gift of Asher B. Durand’s painting Progress (The Advance of Civilization), which was approved by the VMFA Board of Trustees yesterday. One of the most important works of American art in private hands, this is the highest valued gift of a single work of art in VMFA’s history, and represents the first time the painting has been held outside of private collections since it was painted in 1853. Because of the extraordinary generosity of the donor, this beloved, canonical painting now enters the public domain, allowing the citizens of Virginia to be among the first to benefit from its presence in its new home at VMFA. Commissioned by the financier and industrialist Charles Gould (1811–1870), this work complements VMFA’s collection of paintings by other Hudson River School artists, including Thomas Cole, Jasper Francis Cropsey, Frederic Edwin Church, George Inness and Robert Seldon Duncanson. Only a handful of masterpieces in American art—including Thomas Cole’s The Oxbow and George Inness’s The Lackawanna Valley (which hang in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery of Art respectively)—rival Progress in dramatizing the meeting of nature and civilization. -

The Hudson River School

Art, Artists and Nature: The Hudson River School The landscape paintings created by the 19 th century artist known as the Hudson River School celebrate the majestic beauty of the American wilderness. Students will learn about the elements of art, early 19 th century American culture, the creative process, environmental concerns and the connections to the birth of American literature. New York State Standards: Elementary, Intermediate, and Commencement The Visual Arts – Standards 1, 2, 3, 4 Social Studies – Standards 1, 3 ELA – Standards 1, 3, 4 BRIEF HISTORY By the mid-nineteenth century, the United States was no longer the vast, wild frontier it had been just one hundred years earlier. Cities and industries determined where the wilderness would remain, and a clear shift in feeling toward the American wilderness was increasingly ruled by a new found reverence and longing for the undisturbed land. At the same time, European influences - including the European Romantic Movement - continued to shape much of American thought, along with other influences that were distinctly and uniquely American. The traditions of American Indians and their relationship with nature became a recognizable part of this distinctly American Romanticism. American writers put words to this new romantic view of nature in their works, further influencing the evolution of American thought about the natural world. It found means of expression not only in literature, but in the visual arts as well. A focus on the beauty of the wilderness became the passion for many artists, the most notable came to be known as the Hudson River School Artists. The Hudson River School was a group of painters, who between 1820s and the late nineteenth century, established the first true tradition of landscape painting in the United States. -

The Artist and the American Land

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1975 A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land Norman A. Geske Director at Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska- Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Geske, Norman A., "A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land" (1975). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 112. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/112 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME I is the book on which this exhibition is based: A Sense at Place The Artist and The American Land By Alan Gussow Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 79-154250 COVER: GUSSOW (DETAIL) "LOOSESTRIFE AND WINEBERRIES", 1965 Courtesy Washburn Galleries, Inc. New York a s~ns~ 0 ac~ THE ARTIST AND THE AMERICAN LAND VOLUME II [1 Lenders - Joslyn Art Museum ALLEN MEMORIAL ART MUSEUM, OBERLIN COLLEGE, Oberlin, Ohio MUNSON-WILLIAMS-PROCTOR INSTITUTE, Utica, New York AMERICAN REPUBLIC INSURANCE COMPANY, Des Moines, Iowa MUSEUM OF ART, THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY, University Park AMON CARTER MUSEUM, Fort Worth MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON MR. TOM BARTEK, Omaha NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, Washington, D.C. MR. THOMAS HART BENTON, Kansas City, Missouri NEBRASKA ART ASSOCIATION, Lincoln MR. AND MRS. EDMUND c. -

America Past

A Teacher’s Guide to America Past Sixteen 15-minute programs on the social history of the United States for high school students Guide writer: Jim Fleet Series consultant: John Patrick 01987 KRMA-W, Denver, Colorado and Agency for Instructional Technology Bloomington, Indiana AH rights reserved. This guide, or any part of it, may not be reproduced without written permission. Review questions in this guide maybe reproduced and distributed free to students. All inquiries should be addressed to: Agency for Instructional Technology Box A Bloomington, Indiana 47402 Table Of Contents Introduction To The AmericaPastSeries . 4 About Jim Fleet . ...!.... 5 America Past: An Overview . 5 How To Use This Guide . 5 Sources On People And Places In America Past . 5 Programs I. New Spain . 6 2. New France . 9 3. The Southern Colonies . 11 4. New England Colonies . 13 5. Canals and Steamboats . 16 6. Roads and Railroads, . .19 7. The Artist’s View . ... ..,.. 22 8. The Writer’s View . ...25 9. The Abolitionists . ...27 10. The Role of Women . ...29 ll. Utopias . ...31 12. Religion . ...33 13. Social Life . ...35 14. Moving West . ...38 15. The Industrial North . ...41 16. The Antebellum South . ...43 Textbook Correlation Chart . ...46 AnswerKey . ...48 Introduction To The America Past Series Over the past thirty years, it has been my experience that most textbooks and visual aids do an adequate job of cover- ing the political and economic aspects of American history UntiI recently however, scant attention has been given to social history. America Past was created to fill that gap. Some programs, such as those on religion and utopias, elaborate upon topics that may receive only a paragraph or two in many texts. -

Judit Nagy Cultural Encounters on the Canvas

JUDIT NAGY CULTURAL ENCOUNTERS ON THE CANVAS: EUROPEAN INFLUENCES ON CANADIAN LANDSCAPE PAINTING 1867–1890 Introduction Whereas the second half of the 19th century is known as the age of transition in Victorian England, the post-confederation decades of the same century can be termed the age of possibilities in Canadian landscape painting, both transition and possibilities referring to a stage of devel- opment which focuses on potentialities and entails cultural encounters. Fuelled both by Europe’s cultural imprint and the refreshing impressions of the new land, contemporary Canadian landscapists of backgrounds often revealing European ties tried their hands at a multiplicity and mixture of styles. No underlying homogenous Canadian movement of art supported their endeavour though certain tendencies are observable in the colourful cavalcade of works conceived during this period. After providing a general overview of the era in Canadian landscape painting, the current paper will discuss the oeuvre of two landscapists of the time, the English-trained Allan Edson, and the German immigrant painter Otto Reinhold Jacobi1 to illustrate the scope of the ongoing experimentation with colour and light and to demonstrate the extent of European influence on contemporary Canadian landscape art. 1 Members of the Canadian Society of Artists, both Edson and Jacobi were exceptional in the sense that, unlike many landscapists at Confederation, they traded in their European settings into genuine Canadian ones. In general, “artists exhibited more scenes of England and the Continent than of Ontario and Quebec.” (Harper 179) 133 An overview of the era in landscape painting Meaning to capture the spirit of the given period in Canadian history, W. -

The Hudson River School of Artist

THE HUDSON RIVER SCHOOL OF ARTIST The following is a list of painters in the Hudson River School, a midth-century American art . a Hudson River School artist, and the two painted similar subjects. Sister Julie Hart Beers (Kempson) was also a landscape artist of this school. A rusted silo looms over a parking lot where he had seen dirt roads and marshland. Albert Bierstadt painted mountain landscapes on enormous canvases which included pictures of wild scenery filled with mists and clouds. It was promoted as a single-picture attraction—i. The Hudson River School origins date back to these romantic and nationalism ages of America. Fully illustrated, this website brings a personal dimension to the artists of the 19th century. The Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut houses one of the largest collections of paintings by artists of the Hudson River School. So where Cropsey saw unkempt groves and choppy currents buffeting sailboats from a window there, we consoled ourselves with views of not much more than a fenced-off duck pond in the shadow of a street overpass. However, a new American school of landscape painting was about to emerge along with a new form of public entertainment — the art museum. Cole painted pictures as depicted by the novelist. If Cole is rightly designated the founder of the school, then its beginnings appear with his arrival in New York City in Advertisement People fishing there were staring at the water and their rods. Rain was threatening by the time I scrambled back up to the main trail, so we flagged down a passing flatbed truck for a ride to our car. -

Caroline Peart, American Artist

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Humanities MOMENTS OF LIGHT AND YEARS OF AGONY: CAROLINE PEART, AMERICAN ARTIST 1870-1963 A Dissertation in American Studies by Katharine John Snider ©2018 Katharine John Snider Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 The dissertation of Katharine John Snider was reviewed and approved* by the following: Anne A. Verplanck Associate Professor of American Studies and Heritage Studies Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Charles Kupfer Associate Professor of American Studies and History John R. Haddad Professor of American Studies and Popular Culture Program Chair Holly Angelique Professor of Community Psychology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the life of American artist Caroline Peart (1870-1963) within the context of female artists at the turn of the twentieth century. Many of these artists’ stories remain untold as so few women achieved notoriety in the field and female artists are a relatively new area of robust academic interest. Caroline began her formal training at The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts at a pivotal moment in the American art scene. Women were entering art academies at record numbers, and Caroline was among a cadre of women who finally had access to formal education. Her family had the wealth to support her artistic interest and to secure Caroline’s position with other elite Philadelphia-area families. In addition to her training at the Academy, Caroline frequently traveled to Europe to paint and she studied at the Academie Carmen. -

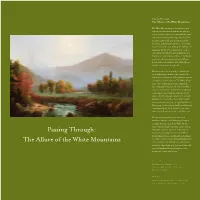

Passing Through: the Allure of the White Mountains

Passing Through: The Allure of the White Mountains The White Mountains presented nineteenth- century travelers with an American landscape: tamed and welcoming areas surrounded by raw and often terrifying wilderness. Drawn by the natural beauty of the area as well as geologic, botanical, and cultural curiosities, the wealthy began touring the area, seeking the sublime and inspiring. By the 1830s, many small-town tav- erns and rural farmers began lodging the new travelers as a way to make ends meet. Gradually, profit-minded entrepreneurs opened larger hotels with better facilities. The White Moun- tains became a mecca for the elite. The less well-to-do were able to join the elite after midcentury, thanks to the arrival of the railroad and an increase in the number of more affordable accommodations. The White Moun- tains, close to large East Coast populations, were alluringly beautiful. After the Civil War, a cascade of tourists from the lower-middle class to the upper class began choosing the moun- tains as their destination. A new style of travel developed as the middle-class tourists sought amusement and recreation in a packaged form. This group of travelers was used to working and commuting by the clock. Travel became more time-oriented, space-specific, and democratic. The speed of train travel, the increased numbers of guests, and a widening variety of accommodations opened the White Moun- tains to larger groups of people. As the nation turned its collective eyes west or focused on Passing Through: the benefits of industrialization, the White Mountains provided a nearby and increasingly accessible escape from the multiplying pressures The Allure of the White Mountains of modern life, but with urban comforts and amenities. -

A „Fekete Legenda” Árnyékában

AAA „FEKETE LEGENDA” ÁRNYÉKÁBAN SZTE BÖLCSÉSZETTUDOMÁNYI KAR TÖRTÉNETTUDOMÁNYI DOKTORI ISKOLA MODERNKORI TÖRTÉNETI PROGRAM PHD ÉRTEKEZÉSEK Farkas Pálma Adél A „FEKETE LEGENDA” ÁRNYÉKÁBAN SPANYOLORSZÁG ÉS AZ EGYESÜLT ÁLLAMOK KAPCSOLATA A KORABELI SAJTÓ TÜKRÉBEN MIGUEL PRIMO DE RIVERA DIKTATÚRÁJA IDEJÉN (1923–1930) Doktori értekezés Szeged, 2013 SZTE BÖLCSÉSZETTUDOMÁNYI KAR Történettudományi Doktori Iskola Modernkori Történeti Program PhD értekezések Szerkesztette: ANDERLE ÁDÁM Technikai szerkeszt ő: JENEY ZSUZSANNA © FARKAS PÁLMA ISBN: 978-963-306-184-8 Felel ős kiadó: J. NAGY LÁSZLÓ Szeged, 2013 Tartalomjegyzék El őszó....................................................................................................................7 Bevezetés ............................................................................................................17 Historiográfiai és forráskérdések ....................................................................17 A múlt lenyomata: a spanyolellenes „fekete legenda” .......................................33 A fekete legenda évszázadai ...........................................................................33 A „ fekete legenda” az Egyesült Államokban .................................................45 A spanyolellenes legenda árnyéka halványul?....................................................57 Spanyolország az észak-amerikai utazó irodalomban.....................................57 „Hispanománia” az észak-amerikai m űvészetekben és építészetben ............58 A fekete legenda ellenszere: -

Download 1 File

n IMITHSONIAN^INSTITUTION NOIinillSNI^NVINOSHllWS S3iavaail LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN~INSTITUTION jviNOSHiiws ssiavaan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniusNi nvinoshiiws ssiavaan in 2 , </> Z W iMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION ^NOIinillSNI NVINOSHilWS S3 I y Vy a \1 LI B RAR I ES^SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION jvinoshiiws S3iavaan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniusNi nvinoshiiws ssiavaan 2 r- Z r z mithsonian~institution NoiiniusNi nvinoshiiws ssiyvyan libraries" smithsonian~institution 3 w \ivinoshiiws 's3 iavaan~LiBRARi es"smithsonian~ institution NoiiniusNi nvinoshiiws"'s3 i a va a 5 _ w =£ OT _ smithsonian^institution NoiiniiiSNrNViNOSHiiws S3 lavaan librari es smithsonian~institution . nvinoshiiws ssiavaan libraries Smithsonian institution NouruiiSNi nvinoshjliws ssiavaan w z y to z • to z u> j_ i- Ul US 5s <=> Yfe ni nvinoshiiws Siiavyan libraries Smithsonian institution NouniiisNi_NviNOSHiiws S3iava LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITU1 ES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIifUllSNI NVINOSHJLIWS S3 I a Va an |NSTITUTION„NOIinillSNI_NVINOSHllWS^S3 I H VU SNI NVINOSH1IWS S3 I ava 8 II LI B RAR I ES..SMITHSONIAN % Es"SMITHSONIAN^INSTITUTION"'NOIinillSNrNVINOSHllWS ''S3IHVHan~LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN_INSTITU OT 2 2 . H <* SNlZWlNOSHilWslsS lavaail^LIBRARI ES^SMITHSONIAN]jNSTITUTION_NOIinil±SNI _NVINOSHllWS_ S3 I UVh r :: \3l ^1) E ^~" _ co — *" — ES "SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION^NOIinillSNI NVINOSH1IWS S3iavaail LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITU '* CO z CO . Z "J Z \ SNI NVINOSHJ.IWS S3iavaan LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIinil±SNI_NVINOSH±IWS S3 I HVi Nineteenth-Century