Guy Debord and the Integrated Spectacle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guy Debord and the Situationist International: Texts and Documents, Edited by Tom Mcdonough G D S I

G D S I OCTOBER BOOKS Rosalind E. Krauss, Annette Michelson, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Hal Foster, Denis Hollier, and Mignon Nixon, editors Broodthaers, edited by Benjamin H. D. Buchloh AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism, edited by Douglas Crimp Aberrations, by Jurgis Baltrusˇaitis Against Architecture: The Writings of Georges Bataille, by Denis Hollier Painting as Model, by Yve-Alain Bois The Destruction of Tilted Arc: Documents, edited by Clara Weyergraf-Serra and Martha Buskirk The Woman in Question, edited by Parveen Adams and Elizabeth Cowie Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century, by Jonathan Crary The Subjectivity Effect in Western Literary Tradition: Essays toward the Release of Shakespeare’s Will, by Joel Fineman Looking Awry: An Introduction to Jacques Lacan through Popular Culture, by Slavoj Zˇizˇek Cinema, Censorship, and the State: The Writings of Nagisa Oshima, by Nagisa Oshima The Optical Unconscious, by Rosalind E. Krauss Gesture and Speech, by André Leroi-Gourhan Compulsive Beauty, by Hal Foster Continuous Project Altered Daily: The Writings of Robert Morris, by Robert Morris Read My Desire: Lacan against the Historicists, by Joan Copjec Fast Cars, Clean Bodies: Decolonization and the Reordering of French Culture, by Kristin Ross Kant after Duchamp, by Thierry de Duve The Duchamp Effect, edited by Martha Buskirk and Mignon Nixon The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century, by Hal Foster October: The Second Decade, 1986–1996, edited by Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Hal Foster, Denis Hollier, and Silvia Kolbowski Infinite Regress: Marcel Duchamp 1910–1941, by David Joselit Caravaggio’s Secrets, by Leo Bersani and Ulysse Dutoit Scenes in a Library: Reading the Photograph in the Book, 1843–1875, by Carol Armstrong Neo-Avantgarde and Culture Industry: Essays on European and American Art from 1955 to 1975, by Benjamin H. -

Real.Izing the Utopian Longing of Experimental Poetry

REAL.IZING THE UTOPIAN LONGING OF EXPERIMENTAL POETRY by Justin Katko Printed version bound in an edition of 20 @ Critical Documents 112 North College #4 Oxford, Ohio 45056 USA http://plantarchy.us REEL EYE SING THO YOU DOH PEON LAWN INC O V.EXPER(T?) I MEANT ALL POET RE: Submitted to the School of Interdisciplinary Studies (Western College Program) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy Interdisciplinary Studies by Justin Katko Miami University Oxford, Ohio April 10, 2006 APPROVED Advisor: _________________ Xiuwu Liu ABSTRACT Capitalist social structure obstructs the potentials of radical subjectivities by over-determining life as a hierarchy of discrete labors. Structural analyses of grammatical syntax reveal the reproduction of capitalist social structure within linguistic structure. Consider how the struggle of articulation is the struggle to make language work.* Assuming an analog mesh between social and docu-textual structures, certain experimental poetries can be read as fractal imaginations of anarcho-Marxist utopianism in their fierce disruption of linguistic convention. An experimental poetry of radical political efficacy must be instantiated by and within micro-social structures negotiated by practically critical attentions to the material conditions of the social web that upholds the writing, starting with writing’s primary dispersion into the social—publishing. There are recent historical moments where such demands were being put into practice. This is a critical supplement to the first issue of Plantarchy, a hand-bound journal of contemporary experimental poetry by American, British, and Canadian practitioners. * Language work you. iii ...as an object of hatred, as the personification of Capital, as the font of the Spectacle. -

Debord, Ressentiment, Ft Re'7o Lutio11ary Anarchism

Debord, Ressentiment, ft Re'7olutio11ary Anarchism Notes on Debord, Ressentiment & Revolutionary Anarchism by Aragorn! Why does the Situationist International continue to be such a rich source of inspiration for anarchist thinkers and activity today? They were a decidedly not anarchist group whose ostensible leader Guy Debord's ideas resonated much more with Marx, Korsh, and Adorno than Bakunin or Kropotkin. Naturally much of the influence of the SI is based on the theory that the general strike in France in May of 1968 represents the highest form of struggle against the dominant order in this historical period. This theory isn't necessarily supported by other social struggles of the past 30 years1 but does correspond nicely to an anarchist frameworkof what social transformation should look like. Therein lies the tension and rationale forthe continuing interest in the SI and Guy's work in particular. If the SI were represented by one book it would be Debord's Society of the Spectacle. If one portion of that book concerns anarchists and particularly anar chist self-knowledge it would be chapter four-The Proletariat as Subject and Representation. Debord damns anarchists' historical failure to theorize or accom plish that goal especially in those times when anarchists were best equipped and positioned to do exactly that. These critiques deserve further examination. In this context we will use the newest translation from Ken Knabb. Aphorism 91 The First International's initial successes enabled it to free itself from the confused influences of the dominant ideology that had survived within it. But the defeat and repression that it soon encountered brought to the surface a conflict between two different conceptions of proletarian revo lution, each of which contained an authoritarian aspect that amounted to abandoning the conscious self-emancipation of the working class. -

Situationists and the 1£ Ch, May 1968

SITUATIONISTS AND THE 1£�CH, MAY 1968 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 1902593383 Published by AK Press/Dark Star AK Press Europe PO Box 12766 Edinburgh EH89YE [email protected] http:/ /www.akuk.com AK Press USA PO BOX40682 San Francisco CA 94140-0682 USA [email protected] http:/ fwww.akpress.org ©This anthology is copyright AK Press/Dark Star 2001 Design by Billy Hunt en tant qu'intelligence de la pratique huma· qui doit etre i reconnue et vccuc _par les masses. This book is dedicated to the memory of Fredy Perlman (1934- 1985) "Having little, being much." C:ONT£NiS Foreword 1 On The Poverty of Student Life 9 Menibers of the lnternationale Situationniste and Students of Strasbourg 2 Our Goals & Methods 29 Situationist International 3 Totality For kids Raoul Vaneigem 4 Paris May 1968 Solidarity 5 The De cline & Fall of the "Spectacular" Commodity-Economy GuyDebord 6 Documents 105 Situationist International 7 Further reading 117 Afterward Foreword This anthology brings together the and in May 1967 it was widely distrib three most widely translated, distrib uted around the Nanterre campus by uted and influential pamphlets of the Anarchists. November of that year saw Situationist International available in the publication of Debord's Society of the sixties. We have also included an the Spectacle and December the publi eyewitness account of the May Events cation of Vaneigem's Revolution of by a member of Solidarity published in Everyday Life. June 1968. (Dark Star would like to What we hope this Anthology will point out that although Solidarity does offer the reader is not only a concise not possess the current 'kudos' or introduction to the ideas of the media/cultural interest possessed by Situationists but also an insight into the Situationists, politically they are what Situationist material was readily deserving of more recognition and available in the late sixties. -

Waste, Obsolescence, and Strategies of Recycling in Twentieth-Century American Literature

ABJECT AMERICANS: WASTE, OBSOLESCENCE, AND STRATEGIES OF RECYCLING IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN LITERATURE By DEREK SCHWARTZ MERRILL A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2006 Copyright 2006 by Derek Schwartz Merrill Dedicated to those fighting the 5 year plan. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Seclusion is necessary to complete a project such as this. During the writing and revising stages it is easy to forget the social aspect of knowledge. To this end, the University of Florida has proven invaluable. My time spent at UF was highly rewarding thanks to the energy and enthusiasm of the faculty and graduate students. The MRG provided the intellectual space and focus necessary to maintaining a critical edge throughout these years. Special thanks goes to the Chair of the Department, John Leavey, whose vision makes this department a dynamic place to study. Thanks to him, the MRG has a national presence of organizing highly engaging conferences. I also want to the thank the staff for all their help over the years: Carla Blount, Loretta Dampier, Melissa Davis, Kaaren Moffat, Jeri White, and Kathy Williams. Finally, I want to acknowledge the students in my classes who have contributed to help me understand the finer aspects of literature and culture. More specifically, I thank my friends in California for their generosity and unflinching support: Carla Hamby, Kris Melberg, Chris Tow, and Rosalia Valencia-Tow. I will always be thankful for their enduring friendship. My family, of course, has also played a vital role in my life by supporting me throughout. -

The Society of the Spectacle Annotated Edition.Pdf

GUY DEBORD THE SOCIETY OF THE SPECTACLE Translated and annotated by Ken Knabb GUY DEBORD THE SOCIETY OF THE SPECTACLE Translated and annotated by Ken Knabb Bureau of Public Secrets Guy Debord's La Societe du Spectadl}was originally published in Paris by Editions Buchet-Chastel (1967) and was reissued by Editions Champ Libre (1971) and Editions Gallimard (1992). This annotated translation by Ken Knabb, published in 2014 by the Bureau of Public Secrets, is not copyrighted. Anyone may freely reproduce or adapt any or all of it. ISBN 978-0-939682-06-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2013951566 Book and cover design: Jeanne Smith Printed in Canada BUREAU OF PUBLIC SECRETS P.O. Box 1044, Berkeley CA 94701 www.bopsecrets.org Contents PREFACE V 1. Separation Perfected 1 2. The Commodity as Spectacle 13 3. Unity and Division Within Appearances 21 4. The Proletariat as Subject and Representation 31 5. Time and History 67 6. Spectacular Time 81 7. Territorial Management 89 8. Negation and Consumption Within Culture 97 9. Ideology Materialized 113 NOTES 119 INDEX 147 PREFACE The first version of this translation of The Society of the Spectacle was completed and posted online at my "Bureau of Public Secrets" website in 2002. The first print version was published by Rebel Press (London) in 2004 and several other editions were subsequently published in various print and digital formats. Meanwhile I continued to fine-tune the version on my website. Although I will continue to tweak the on line version as further improvements occur to me, this new printed edition is probably pretty close to final. -

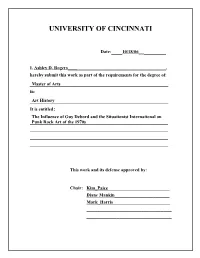

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:____10/18/06__________ I, Ashley D. Rogers___________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: The Influence of Guy Debord and the Situationist International on Punk Rock Art of the 1970s This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Kim_Paice___________________________ Diane Mankin________________________ Mark_Harris_________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ “The Influence of Guy Debord and the Situationist International on Punk Rock Art of the 1970s” A thesis submitted to The Department of Art History of the School of Art/College of DAAP University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Art History of the School of Art 2006 by Ashley D. Rogers Committee Chair: Dr. Kimberly Paice ABSTRACT This study addresses the influence of Guy Debord (1931-1994) and the Situationist International (hereafter SI) on some punk rock art of the 1970s, particularly that of Jamie Reid (b. 1947). It examines the early work of Debord and the Lettrist International, the SI, and the latter groups’ concepts of urbanisme unitaire (integrated city creation), dèrive (a method of moving through urban space), and détournement (a kind of agitprop intervention in posters and in historical icons of art). Dètournement in particular was a key influence on poster art created during the 1968 student/worker protests in France, but the SI imprint is also evident in the graffiti and slogans created during this time of unrest. I further trace how, by way of the events of 1968, the SI went on to influence Reid’s punk rock art in 1970s England. -

Quit While You're Ahead

Bob Black Quit While You’re Ahead 1984 The Anarchist Library The Book of Pleasures. By Raoul Vaneigem Translated by John Fullerton London: Pending Press, 1983 The nostalgia craze has caught up with the Situationist International, al- though a reunion and comeback tour is unlikely. From the nadir of the mid- 1970’s, when the American pro-situationist groups fought themselves to exhaus- tion, interest in the sits has been on the rise in the English-speaking world, es- pecially since Ken Knabb published his translation anthology and Greil Marcus revealed the situationists as the occult inspiration of punk rock. Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle has been available from Black & Red for over twenty years, and the authorized translation of Raoul Vaneigem’s Revolution of Ev- eryday Life for more than ten. “Situationism” is back, if only as an object of contemplation, but it has no avowed practitioners (except absurdity incarnate Bill Brown). As Newsweek used to say, “Where Are They Now?” For the Situationist International the flush times were the early and middle 60’s. Having ousted the aesthetes, the triumphant politicized faction of Debord and Vaneigem turned its mercilessly lucid scorn on global “spectacular” society at its zenith. The spectacle is capital self-confident and fully realized, a self- subsistent structure of appearances which the situationists supoosed they dis- cerned through the welter of “issues” and contingencies. Weberians in Hegelian drag, the sits (Debord above all) constructed an ideal type, the spectacle, capi- talism in its purity and maturity. And it must have seemed that managed capitalism had left behind world wars, colonialism, and all other detractions from the business of realizing itself as a totality. -

The Situationist International

The Situationist International The Situationist International A Critical Handbook Edited by Alastair Hemmens and Gabriel Zacarias First published 2020 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Alastair Hemmens and Gabriel Zacarias 2020 The right of the individual contributors to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3890 3 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3889 7 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7868 0544 7 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0546 1 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0545 4 EPUB eBook This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Contents Introduction: The Situationist International in Critical Perspective 1 Alastair Hemmens and Gabriel Zacarias PART I: KEY CONTEXTS 1 Debord’s Reading of Marx, Lukács and Wittfogel: A Look at the Archives 19 Anselm Jappe 2 The Unsurpassable: Dada, Surrealism and the Situationist International 27 Krzysztof Fijalkowski 3 Lettrism 43 Fabrice Flahutez 4 The Situationists, Hegel and Hegelian Marxism in France 51 Tom Bunyard 5 The Situationist International and the Rediscovery of the Revolutionary Workers’ Movement 71 Anthony Hayes -

Situationist International

10/4/2015 Situationist International - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Situationist International From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other uses, see Situationism (disambiguation). The Situationist International (SI) was an international organization of social activists made up of avant-garde artists, intellectuals, and political theorists, prominent in Europe from its formation in 1957 to its dissolution in 1972.[1] The intellectual foundations of the Situationist International were derived primarily from anti- authoritarian Marxism and the avant-garde art movements of the early 20th century, particularly Dada and Surrealism.[1] Overall, situationist theory represented an attempt to synthesize this diverse field of theoretical disciplines into a modern and comprehensive critique of mid-20th century advanced capitalism.[1] The situationists recognized that capitalism had changed since Marx's formative writings, but maintained that his analysis of the capitalist mode of production remained fundamentally correct; they rearticulated and expanded upon several classical Marxist concepts, such as his theory of alienation.[1] In their expanded interpretation of Marxist theory, the situationists asserted that the misery of social alienation and commodity fetishism were no longer limited to the fundamental components of capitalist society, but had now in advanced capitalism spread themselves to every aspect of life and culture.[1] They rejected the idea that advanced capitalism's apparent successes—such as technological advancement, increased -

Visibility, Protest, and Racial Formation in 1970S Prison Radicalism Dan Berger University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly accessible Penn Dissertations Fall 12-22-2010 "We Are the Revolutionaries": Visibility, Protest, and Racial Formation in 1970s Prison Radicalism Dan Berger University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the African American Studies Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Race, Ethnicity and post-Colonial Studies Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Berger, Dan, ""We Are the Revolutionaries": Visibility, Protest, and Racial Formation in 1970s Prison Radicalism" (2010). Publicly accessible Penn Dissertations. Paper 250. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/250 For more information, please contact [email protected]. "We Are the Revolutionaries": Visibility, Protest, and Racial Formation in 1970s Prison Radicalism Abstract This dissertation analyzes black and Puerto Rican prison protest in the 1970s. I argue that prisoners elucidated a nationalist philosophy of racial formation that saw racism as a site of confinement but racial identity as a vehicle for emancipation. Trying to force the country to see its sites of punishment as discriminatory locations of repression, prisoners used spectacular confrontation to dramatize their conditions of confinement as epitomizing American inequality. I investigate this radicalism as an effort to secure visibility, understood here as a metric of collective consciousness. In documenting the ways prisoners were symbols and spokespeople of 1970s racial protest, this dissertation argues that the prison served as metaphor and metonym in the process of racial formation. -

SI-Part-2-Formatted Copy

IN SITU: situationism & its influence 1957-2010 catalogue 11.5.2 brian cassidy bookseller brian cassidy bookseller 8115 fenton st. suite 207 silver spring md 20910 301-589-0789 (office) 301-244-8868 (mobile) [email protected] www.briancassidy.net [TERMS]: Prices are in US dollars. All material subject to prior sale. Unless otherwise noted, items are originals (meaning not facsimiles or reproductions) and/or first editions (i.e. first printings). All items are guaranteed as described. Returnable with notification and prompt shipment within 30 days. Payment by check or money order (made out to Brian Cassidy); Visa, AmEx, MasterCard, Discover, and Paypal also accepted. Institutions may be accommodated according to their needs. Reciprocal courtesies to the trade. Shipping will be billed. MD sales tax will be added to appropriate purchases. (largely Self-Plagiarized) Introduction to part 2: This is the second (and larger) part of our catalogue on Situationism, and chronicles the SI’s influence. It is (still), however, not a catalogue of high-spot rarities, and this is to some extent by design — but not my design. When Debord and his Situationists by and large eschewed copyright, they helped ensure the spread of their ideas. The subsequent appropriation and dissemination of Situationist texts by numerous sympathizers, collaborators, and associates – as I hope this catalogue demonstrates – became one of its most enduring legacies, one that feels oddly familiar in these days of the re-blog/-tweet/-gram. Indeed, the Situationists seem in many ways like early viral content generators, simultaneously reaching back to the pamphleteering tradition while looking forward to zine culture.