A Study of Value in Fiji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TROPICAL CYCLONE WINSTON SITUATION REPORT 30 of 26/02/2016

NATIONAL EMERGENCY OPERATION CENTER TROPICAL CYCLONE WINSTON SITUATION REPORT 30 of 26/02/2016 This Situation Report is issued by the National Emergency Operation Centre and covers the period from 0800 hours to 1600hours on 26/02/2016. The purpose of this report is to provide the update on the current operations undertaken after TC Winston. 1. STATUS SUMMARY EVENT REMARKS TOTAL CENTRAL WEST EAST NORTH TOTAL Death(s) 9 11 20 2 42 Missing - - - - - Hospitalised 5 17 7 4 33 Injured 24 24 68 10 126 Evacuation 160 339 335 101 935 Centres Evacuees 13,282 33,963 6999 6095 60,339 2. WEATHER OUTLOOK NEOC SITREP 28 / 1 6 P a g e 1 | 29 Issued from the National Weather Forecasting Centre Nadi at 2.30 pm on Friday the 26th of February 2016 A strong wind warning remains in force for Kadavu passage, southern Koro sea and southern Lau waters. Situation: A weak of trough of low pressure with clouds and showers remains low moving over the eastern part of Fiji. It is expected to gradually move west wards and affect the rest of the group till later today. Meanwhile a moist north east wind flow prevails over Fiji. Forecast to midnight for Fiji waters for Kadavu passage southern Koro sea and southern Lau waters, north east winds 20 to 25 knots. Rough seas. Moderate north east swells. Poor visibility in areas of showers and thunderstorm. Further outlook:: East to north east winds 20 to 25 knots, Rough seas. For the rest of Fiji waters north to north east winds, 15 to 20 knots, moderate to rough seas. -

SITUATION REPORT 67 of 09/03/2016

NATIONAL EMERGENCY OPERATION CENTER TROPICAL CYCLONE WINSTON SITUATION REPORT 67 of 09/03/2016 The purpose of this report is to provide the update on the current operations undertaken after TC Winston. This Situation Report is issued by the National Emergency Operation Centre and covers the period from 1600hrs - 2400 hours, 09/03/2016. Updates in this report summarise all reports and briefs submitted from various EOC’s in the four divisions. 1.0 NATIONAL HIGHLIGHTS Further to the current overall national damage assessments conducted by the four divisions and sectoral agencies, damage incurred quantified to a magnitude of $476.8m, however progressively this is subject to change after a series of progressive detailed assessments across all sectoral agencies and the outcome of damage assessments by the DDA Teams deployed by the four divisions. A total of 545 active evacuation centers exist nationwide with the Eastern Division recording the highest with a record of 325 evacuation centers, Western Division has 196 evacuation centers while the Northern Division has 34 evacuation centers. A total of 17953 national evacuees population is recorded as the current total number of evacuees nationwide A total of 306 schools is affected with 23 schools closed for repairs and A total of 16 schools are currently used as evacuation centers occupied by 666 evacuees nationwide. 7 schools in the Western Division in the Ra Province and 9 schools in the Eastern Division, 8 in Lomaiviti and 1 in the Lau Province. Local donations assistance received, quantify to a tune of $4m while internationally we have received more than $50m in cash and kind. -

Data Structure

Data structure – Water The aim of this document is to provide a short and clear description of parameters (data items) that are to be reported in the data collection forms of the Global Monitoring Plan (GMP) data collection campaigns 2013–2014. The data itself should be reported by means of MS Excel sheets as suggested in the document UNEP/POPS/COP.6/INF/31, chapter 2.3, p. 22. Aggregated data can also be reported via on-line forms available in the GMP data warehouse (GMP DWH). Structure of the database and associated code lists are based on following documents, recommendations and expert opinions as adopted by the Stockholm Convention COP6 in 2013: · Guidance on the Global Monitoring Plan for Persistent Organic Pollutants UNEP/POPS/COP.6/INF/31 (version January 2013) · Conclusions of the Meeting of the Global Coordination Group and Regional Organization Groups for the Global Monitoring Plan for POPs, held in Geneva, 10–12 October 2012 · Conclusions of the Meeting of the expert group on data handling under the global monitoring plan for persistent organic pollutants, held in Brno, Czech Republic, 13-15 June 2012 The individual reported data component is inserted as: · free text or number (e.g. Site name, Monitoring programme, Value) · a defined item selected from a particular code list (e.g., Country, Chemical – group, Sampling). All code lists (i.e., allowed values for individual parameters) are enclosed in this document, either in a particular section (e.g., Region, Method) or listed separately in the annexes below (Country, Chemical – group, Parameter) for your reference. -

Survival Guide on the Road

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd PAGE ON THE YOUR COMPLETE DESTINATION GUIDE 42 In-depth reviews, detailed listings ROAD and insider tips Vanua Levu & Taveuni p150 The Mamanuca & Yasawa Groups p112 Ovalau & the Lomaiviti Group Nadi, Suva & Viti Levu p137 p44 Kadavu, Lau & Moala Groups p181 PAGE SURVIVAL VITAL PRACTICAL INFORMATION TO 223 GUIDE HELP YOU HAVE A SMOOTH TRIP Directory A–Z .................. 224 Transport ......................... 232 Directory Language ......................... 240 student-travel agencies A–Z discounts on internatio airfares to full-time stu who have an Internatio Post offices 8am to 4pm Student Identity Card ( Accommodation Monday to Friday and 8am Application forms are a Index ................................ 256 to 11.30am Saturday Five-star hotels, B&Bs, able at these travel age Restaurants lunch 11am to hostels, motels, resorts, tree- Student discounts are 2pm, dinner 6pm to 9pm houses, bungalows on the sionally given for entr or 10pm beach, campgrounds and vil- restaurants and acco lage homestays – there’s no Shops 9am to 5pm Monday dation in Fiji. You ca Map Legend ..................... 263 to Friday and 9am to 1pm the student health shortage of accommodation ptions in Fiji. See the ‘Which Saturday the University of nd?’ chapter, p 25 , for PaciÀ c (USP) in ng tips and a run-down hese options. Customs Regulations E l e c t r Visitors can leave Fiji without THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Dean Starnes, Celeste Brash, Virginia Jealous “All you’ve got to do is decide to go and the hardest part is over. So go!” TONY WHEELER, COFOUNDER – LONELY PLANET Get the right guides for your trip PAGE PLAN YOUR PLANNING TOOL KIT 2 Photos, itineraries, lists and suggestions YOUR TRIP to help you put together your perfect trip Welcome to Fiji ............... -

1 the Fiji Museum's Efforts Towards the Preservation of Underwater Cultural Heritage Sites in Fiji Elia Nakoro History Archaeo

The Fiji Museum’s efforts towards the Preservation of Underwater Cultural Heritage Sites in Fiji Elia Nakoro History Archaeology Department, The Fiji Museum, Thurston Gardens, Suva Fiji Email: [email protected] Abstract Fiji’s 300 isles are enclosed within a total sea area of about 1,260,000km2 of its Exclusive Economic Zone and to date very little work has been carried out on underwater and maritime archaeology. Resource materials documented by the Archaeology Department of the Fiji Museum have identified more than 500 shipwrecks, a great number of which were wrecked less than 50 years ago. The establishment of an Underwater Unit at the Fiji Museum is needed to safeguard the nation’s underwater historic sites and raise awareness towards understanding the untold sunken mysteries that connect Fiji to the world; however there are several issues that need to be addressed in order for this Unit to be established and run effectively. This paper discusses the need for further capacity building and training in Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) studies to successfully document, survey and protect Fiji’s underwater cultural sites. Furthermore, the area of developing policy papers, funding proposals and the documentation of findings will also require special attention to sustain UCH projects. Alike the other developing countries, the paper highlights the daunting challenges that face the Fiji Museum including the lack of human resources, equipment and above all insufficient funding to carry out this much needed work. Key words: Capacity building, Collaboration, Levuka Town, Sacred, Underwater Cultural Heritage, World Heritage Site Introduction The Fiji Islands The Republic of the Fiji Islands encompasses a group of over 300 volcanic island landmasses, of which over 100 islands are inhabited. -

We Are Kai Tonga”

5. “We are Kai Tonga” The islands of Moala, Totoya and Matuku, collectively known as the Yasayasa Moala, lie between 100 and 130 kilometres south-east of Viti Levu and approximately the same distance south-west of Lakeba. While, during the nineteenth century, the three islands owed some allegiance to Bau, there existed also several family connections with Lakeba. The most prominent of the few practising Christians there was Donumailulu, or Donu who, after lotuing while living on Lakeba, brought the faith to Moala when he returned there in 1852.1 Because of his conversion, Donu was soon forced to leave the island’s principal village, Navucunimasi, now known as Naroi. He took refuge in the village of Vunuku where, with the aid of a Tongan teacher, he introduced Christianity.2 Donu’s home island and its two nearest neighbours were to be the scene of Ma`afu’s first military adventures, ostensibly undertaken in the cause of the lotu. Richard Lyth, still working on Lakeba, paid a pastoral visit to the Yasayasa Moala in October 1852. Despite the precarious state of Christianity on Moala itself, Lyth departed in optimistic mood, largely because of his confidence in Donu, “a very steady consistent man”.3 He observed that two young Moalan chiefs “who really ruled the land, remained determined haters of the truth”.4 On Matuku, which he also visited, all villages had accepted the lotu except the principal one, Dawaleka, to which Tui Nayau was vasu.5 The missionary’s qualified optimism was shattered in November when news reached Lakeba of an attack on Vunuku by the two chiefs opposed to the lotu. -

Reef Check Description of the 2000 Mass Coral Beaching Event in Fiji with Reference to the South Pacific

REEF CHECK DESCRIPTION OF THE 2000 MASS CORAL BEACHING EVENT IN FIJI WITH REFERENCE TO THE SOUTH PACIFIC Edward R. Lovell Biological Consultants, Fiji March, 2000 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................4 2.0 Methods.........................................................................................................................................4 3.0 The Bleaching Event .....................................................................................................................5 3.1 Background ................................................................................................................................5 3.2 South Pacific Context................................................................................................................6 3.2.1 Degree Heating Weeks.......................................................................................................6 3.3 Assessment ..............................................................................................................................11 3.4 Aerial flight .............................................................................................................................11 4.0 Survey Sites.................................................................................................................................13 4.1 Northern Vanua Levu Survey..................................................................................................13 -

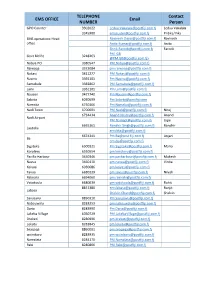

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Is Fiji Ready for a Free Press

VOLUME 17. No.1I/MAY, 2012 ISSN 1029-7316 Pageant scrutiny by EDWARD TAVANAVANUA and PARIJATA GURDAYAL scheduled for the panel to view and assess the contestants. Hoerder, who has experience as HE Miss World Fiji 2012 Pageant is under a Miss Hibiscus judge, said the fact that they scrutiny following a plethora of allegations, only had one meeting with the contestants including that the winner was pre-deter- T was extremely irregular. The assessment also mined well before the judging panel deliberated. was confined to their life story or experiences. Although the pageant concluded about two Blake has since confirmed in a press state- weeks ago, the Miss World Organisation has ment that no judging criteria or points system yet to add the winner of the Fiji franchise, was used to judge the contestants. Torika Watters, to the list of winners on its official “If you are asked to be a judge for Miss World, website. The organisation has yet to respond to then you should come with the mindset of hear- queries e-mailed to it last week. Extra ing genuine stories and not with the expecta- Fiji franchise director Andhy Blake refused requests tions of age, point’s tabulation,” he said. yards for an in-person interview. When asked over the phone He added that based on this fact that no judging whether Watters had been accepted into the interna- or points system was employed, any allegations of pay off tional competition, he said “it’s a surprise”. judging being rigged are false. He also declined to comment on whether the funds “I gave my own personal opin- raised from a charity ball, which was held to create ions on whoever I saw fitting for awareness on mental health, had been given to St Giles the title without influencing the Hospital. -

Rethinking Pacific Climate Change Adaptation Janie Ruth Walker

I just want to be myself: Rethinking Pacific climate change adaptation Janie Ruth Walker A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Development Studies School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences Victoria University of Wellington 2019 Cover photo: A jandal, a coconut, modern, traditional: both valued. All photos were taken by the author, except where otherwise stated. ii Prologue I talk about the moonbow I saw at night, in the middle of our vast ocean. This is good luck, they say, and we are lost in phenomena and ways of knowing the ocean that connects us. Ratu had told me that after our conversation that the ‘Va’ space between us had diminished. As I consider what he means, I walk through the Suva streets to the bus depot. It’s so hot: I’m sticky and uncomfortable. The bus arrives and I clamber on, across the debris of paper bus tickets in the gutter; my too many bags getting in the way, thoughts shut out from the loud beats of the bus. A young girl stares. I smile, too keen. She waits. I turn and look out the window at the harbour clogged with wrecks and foreign ships. I look at the girl again and wait until the space between us opens. (Author’s personal journal, 2018). iii iv Abstract Climate change is now being presented as the biggest future threat to humanity. Many people living in the Pacific Islands are experiencing this threat through the extreme negative impacts of climate change without largely having produced the human-induced causes. -

Researchspace@Auckland

http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz ResearchSpace@Auckland Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. To request permissions please use the Feedback form on our webpage. http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/feedback General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. CONNECTING IDENTITIES AND RELATIONSHIPS THROUGH INDIGENOUS EPISTEMOLOGY: THE SOLOMONI OF FIJI ESETA MATEIVITI-TULAVU A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Auckland Auckland, New Zealand 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................. vi Dedication ............................................................................................................................