In Horto Feritas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Ecology of Water Relations in Plants". In: Encyclopedia of Life

Ecology of Water Relations Advanced article in Plants Article Contents . Introduction Yoseph Negusse Araya, The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK . Water Uptake and Movement through Plants . Water Stress and Plants Water is an important resource for plant growth. Availability of water in the soil determines . Plant Sensing and Adaptation to Water Stress the niche, distribution and competitive interaction of plants in the environment. Distribution of Plants in Response to Water Regime Introduction doi: 10.1002/9780470015902.a0003201 Importance of water for plants Moisture Water typically constitutes 80–95% of the mass of growing 8 plant tissues and plays a crucial role for plant growth (Taiz 7 and Zeiger, 1998). Plants require water for a number of 6 physiological processes (e.g. synthesis of carbohydrates) 5 and for associated physical functions (e.g. keeping plants turgid). 4 Water accomplishes its many functions because of its 3 Moisture index 2 unique characteristics: the polarity of the molecule H2O (which makes it an excellent solvent), viscosity (which 1 makes it capable of moving through plant tissues by 0 capillary action) and thermal properties (which makes it Forest Woodland Grassland Desert capable of cooling plant tissues). Total net productivity 1 Plants require water, soil nutrients, carbon dioxide, ox- − 1000 year ygen and solar radiation for growth. Of these, water is most 2 − often the most limiting: influencing productivity (Taiz and m 1 800 Zeiger, 1998) as well as the diversity of species (Rodriguez- − Iturbe and Porporato, 2004) in both natural and agricul- 600 tural ecosystems. This is illustrated graphically in Figure 1. 400 How does water affect ecology of plants? 200 In order to understand the ecology of plant–water rela- 0 Total net productivity g Total tions it is important to understand from where and how Forest Woodland Grassland Desert plants acquire water in their environment (the latter is dis- cussed in the section on water uptake and movement Plant species diversity through plants). -

Bulb Dormancy in Vitro—Fritillaria Meleagris: Initiation, Release and Physiological Parameters

plants Review Bulb Dormancy In Vitro—Fritillaria meleagris: Initiation, Release and Physiological Parameters Marija Markovi´c*, Milana Trifunovi´cMomˇcilov , Branka Uzelac , Sladana¯ Jevremovi´c and Angelina Suboti´c Department of Plant Physiology, Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stankovi´c“—NationalInstitute of the Republic of Serbia, University of Belgrade, Bulevar Despota Stefana 142, 11060 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] (M.T.M.); [email protected] (B.U.); [email protected] (S.J.); [email protected] (A.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In ornamental geophytes, conventional vegetative propagation is not economically feasible due to very slow development and ineffective methods. It can take several years until a new plant is formed and commercial profitability is achieved. Therefore, micropropagation techniques have been developed to increase the multiplication rate and thus shorten the multiplication and regeneration period. The majority of these techniques rely on the formation of new bulbs and their sprouting. Dormancy is one of the main limiting factors to speed up multiplication in vitro. Bulbous species have a period of bulb dormancy which enables them to survive unfavorable natural conditions. Bulbs grown in vitro also exhibit dormancy, which has to be overcome in order to allow sprouting of bulbs in the next vegetation period. During the period of dormancy, numerous physiological processes occur, many of which have not been elucidated yet. Understanding the process of dormancy will allow us to speed up and improve breeding of geophytes and thereby achieve economic profitability, which is very important for horticulture. This review focuses on recent findings in the area of Citation: Markovi´c,M.; Momˇcilov, bulb dormancy initiation and release in fritillaries, with particular emphasis on the effect of plant M.T.; Uzelac, B.; Jevremovi´c,S.; growth regulators and low-temperature pretreatment on dormancy release in relation to induction of Suboti´c,A. -

Alyssum) and the Correct Name of the Goldentuft Alyssum

ARNOLDIA VE 1 A continuation of the BULLETIN OF POPULAR INFORMATION of the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University VOLUME 26 JUNE 17, 1966 NUMBERS 6-7 ORNAMENTAL MADWORTS (ALYSSUM) AND THE CORRECT NAME OF THE GOLDENTUFT ALYSSUM of the standard horticultural reference works list the "Madworts" as MANYa group of annuals, biennials, perennials or subshrubs in the family Cru- ciferae, which with the exception of a few species, including the goldentuft mad- wort, are not widely cultivated. The purposes of this article are twofold. First, to inform interested gardeners, horticulturists and plantsmen that this exception, with a number of cultivars, does not belong to the genus Alyssum, but because of certain critical and technical characters, should be placed in the genus Aurinia of the same family. The second goal is to emphasize that many species of the "true" .~lyssum are notable ornamentals and merit greater popularity and cul- tivation. The genus Alyssum (now containing approximately one hundred and ninety species) was described by Linnaeus in 1753 and based on A. montanum, a wide- spread European species which is cultivated to a limited extent only. However, as medicinal and ornamental garden plants the genus was known in cultivation as early as 1650. The name Alyssum is of Greek derivation : a meaning not, and lyssa alluding to madness, rage or hydrophobia. Accordingly, the names Mad- wort and Alyssum both refer to the plant’s reputation as an officinal herb. An infu- sion concocted from the leaves and flowers was reputed to have been administered as a specific antidote against madness or the bite of a rabid dog. -

ED45E Rare and Scarce Species Hierarchy.Pdf

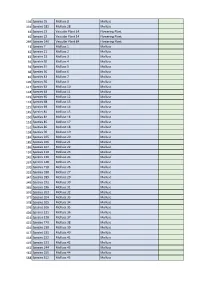

104 Species 55 Mollusc 8 Mollusc 334 Species 181 Mollusc 28 Mollusc 44 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 45 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 269 Species 149 Vascular Plant 84 Flowering Plant 13 Species 7 Mollusc 1 Mollusc 42 Species 21 Mollusc 2 Mollusc 43 Species 22 Mollusc 3 Mollusc 59 Species 30 Mollusc 4 Mollusc 59 Species 31 Mollusc 5 Mollusc 68 Species 36 Mollusc 6 Mollusc 81 Species 43 Mollusc 7 Mollusc 105 Species 56 Mollusc 9 Mollusc 117 Species 63 Mollusc 10 Mollusc 118 Species 64 Mollusc 11 Mollusc 119 Species 65 Mollusc 12 Mollusc 124 Species 68 Mollusc 13 Mollusc 125 Species 69 Mollusc 14 Mollusc 145 Species 81 Mollusc 15 Mollusc 150 Species 84 Mollusc 16 Mollusc 151 Species 85 Mollusc 17 Mollusc 152 Species 86 Mollusc 18 Mollusc 158 Species 90 Mollusc 19 Mollusc 184 Species 105 Mollusc 20 Mollusc 185 Species 106 Mollusc 21 Mollusc 186 Species 107 Mollusc 22 Mollusc 191 Species 110 Mollusc 23 Mollusc 245 Species 136 Mollusc 24 Mollusc 267 Species 148 Mollusc 25 Mollusc 270 Species 150 Mollusc 26 Mollusc 333 Species 180 Mollusc 27 Mollusc 347 Species 189 Mollusc 29 Mollusc 349 Species 191 Mollusc 30 Mollusc 365 Species 196 Mollusc 31 Mollusc 376 Species 203 Mollusc 32 Mollusc 377 Species 204 Mollusc 33 Mollusc 378 Species 205 Mollusc 34 Mollusc 379 Species 206 Mollusc 35 Mollusc 404 Species 221 Mollusc 36 Mollusc 414 Species 228 Mollusc 37 Mollusc 415 Species 229 Mollusc 38 Mollusc 416 Species 230 Mollusc 39 Mollusc 417 Species 231 Mollusc 40 Mollusc 418 Species 232 Mollusc 41 Mollusc 419 Species 233 -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Notes on Neotropical Proconiini (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae: Cicadellinae), IV: Lectotype Designations of Aulacizes Amyot &

Arthropod Systematics & Phylogeny 105 64 (1) 105–111 © Museum für Tierkunde Dresden, ISSN 1863-7221, 30.10.2006 Notes on Neotropical Proconiini (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae: Cicadellinae), IV: lectotype designations of Aulacizes Amyot & Audinet-Serville species described by Germar and revalidation of A. erythrocephala (Germar, 1821) GABRIEL MEJDALANI 1, DANIELA M. TAKIYA 2 & RACHEL A. CARVALHO 1 1 Departamento de Entomologia, Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Quinta da Boa Vista, São Cristóvão, 20940-040 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil [[email protected]] 2 Center for Biodiversity, Illinois Natural History Survey, 1816 S. Oak Street, Champaign, IL 61820, USA [[email protected]] Received 17.iii.2005, accepted 22.viii.2006. Available online at www.arthropod-systematics.de > Abstract Lectotypes are designated for the sharpshooter species Aulacizes erythrocephala (Germar, 1821) and A. quadripunctata (Germar, 1821) based on recently located specimens from the Germar collection. The former species is reinstated from synonymy of the latter one and is redescribed and illustrated based on specimens from Southeastern Brazil. The male and female genitalia are described for the fi rst time. The two species are similar morphologically, but they can be easily distinguished from each other, as well as from the other species of the genus, by their color patterns. > Key words Membracoidea, Aulacizes quadripunctata, leafhopper, sharpshooter, taxonomy, morphology, Brazil. 1. Introduction This is the fourth paper of a series on the taxonomy redescribed and illustrated. One sharpshooter type of the leafhopper tribe Proconiini in the Neotropical located in the Germar collection (Homalodisca vitri- region. The fi rst three papers included descriptions of pennis (Germar, Year 1821)) was previously designated two new species and notes on other species in the tribe by TAKIYA et al. -

Conserving Europe's Threatened Plants

Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation By Suzanne Sharrock and Meirion Jones May 2009 Recommended citation: Sharrock, S. and Jones, M., 2009. Conserving Europe’s threatened plants: Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Botanic Gardens Conservation International, Richmond, UK ISBN 978-1-905164-30-1 Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW, UK Design: John Morgan, [email protected] Acknowledgements The work of establishing a consolidated list of threatened Photo credits European plants was first initiated by Hugh Synge who developed the original database on which this report is based. All images are credited to BGCI with the exceptions of: We are most grateful to Hugh for providing this database to page 5, Nikos Krigas; page 8. Christophe Libert; page 10, BGCI and advising on further development of the list. The Pawel Kos; page 12 (upper), Nikos Krigas; page 14: James exacting task of inputting data from national Red Lists was Hitchmough; page 16 (lower), Jože Bavcon; page 17 (upper), carried out by Chris Cockel and without his dedicated work, the Nkos Krigas; page 20 (upper), Anca Sarbu; page 21, Nikos list would not have been completed. Thank you for your efforts Krigas; page 22 (upper) Simon Williams; page 22 (lower), RBG Chris. We are grateful to all the members of the European Kew; page 23 (upper), Jo Packet; page 23 (lower), Sandrine Botanic Gardens Consortium and other colleagues from Europe Godefroid; page 24 (upper) Jože Bavcon; page 24 (lower), Frank who provided essential advice, guidance and supplementary Scumacher; page 25 (upper) Michael Burkart; page 25, (lower) information on the species included in the database. -

Research Regarding the Melliferous Charactheristics of Labiates from Xerophile Meadows from Danube Valley

Lucr ări ştiin Ńifice Zootehnie şi Biotehnologii , vol. 41(1) (2008 ), Timi şoara RESEARCH REGARDING THE MELLIFEROUS CHARACTHERISTICS OF LABIATES FROM XEROPHILE MEADOWS FROM DANUBE VALLEY CERCET ĂRI ASUPRA VALORII MELIFERE A LAMIACEELOR DIN PAJI ŞTILE XEROFITE DIN LUNCA DUN ĂRII ION NICOLETA Apiculture Research and Development Institute of Bucharest, Romania The xerophile meadows in the Danube Valley are dry meadows, located at a great distance from the Danube and with underground waters at greater depth. Their floral composition is characterized by a small number of species pertaining to both mezoxerophiles and to xerophiles, yet the highest percentage is covered by xerophile species, which are characterized by their small foliage surface, the very narrow and tough limb, and acute porosity etc.In the floral composition of these species, the graminaceae species are best represented, followed by leguminous and lamiaceae, known in beekeeping as good honey plants. Thus, the researches carried out have shown that Lamiaceae species have a good participation, with variation limits raging from 15% to 50-60%. Leguminous species are represented less on xerophile meadows than in hidrophile meadows. Among these we mention: Lotus corniculatus L., Trifolium repens L. şi Medicago lupulina L., all these species being known in beekeeping as good honey plants. Among gramineae species the most representatives are: Lolium perene L. and Poa pratensis L., yet with no melliferous value. Likewise, the group of „various” plants varied a lot as participation in the structure of the vegetal cover of xerophile meadows, depending on the place of research, all these species having no melliferous value. The current paper describes the results o biometric and melliferous researches carried out over the period 2003- 2005 on 5 plant species pertaining to the Lamiaceae family, namely: Salvia nemerosa L. -

Exploring Patterns of Variation Within the Central-European Tephroseris Longifolia Agg.: Karyological and Morphological Study

Preslia 87: 163–194, 2015 163 Exploring patterns of variation within the central-European Tephroseris longifolia agg.: karyological and morphological study Karyologická a morfologická variabilita v rámci Tephroseris longifolia agg. Katarína O l š a v s k á1, Barbora Šingliarová1, Judita K o c h j a r o v á1,3, Zuzana Labdíková2,IvetaŠkodová1, Katarína H e g e d ü š o v á1 &MonikaJanišová1 1Institute of Botany, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Dúbravská cesta 9, SK-84523 Bratislava, Slovakia, e-mail: [email protected]; 2Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Matej Bel, Tajovského 40, SK-97401 Banská Bystrica, Slovakia; 3Comenius University, Bratislava, Botanical Garden – detached unit, SK-03815 Blatnica, Slovakia Olšavská K., Šingliarová B., Kochjarová J., LabdíkováZ.,ŠkodováI.,HegedüšováK.&JanišováM. (2015): Exploring patterns of variation within the central-European Tephroseris longifolia agg.: karyological and morphological study. – Preslia 87: 163–194. Tephroseris longifolia agg. is an intricate complex of perennial outcrossing herbaceous plants. Recently, five subspecies with rather separate distributions and different geographic patterns were assigned to the aggregate: T. longifolia subsp. longifolia, subsp. pseudocrispa and subsp. gaudinii predominate in the Eastern Alps; the distribution of subsp. brachychaeta is confined to the northern and central Apennines and subsp. moravica is endemic in the Western Carpathians. Carpathian taxon T. l. subsp. moravica is known only from nine localities in Slovakia and the Czech Republic and is treated as an endangered taxon of European importance (according to Natura 2000 network). As the taxonomy of this aggregate is not comprehensively elaborated the aim of this study was to detect variability within the Tephroseris longifolia agg. -

The Leafhoppers of Minnesota

Technical Bulletin 155 June 1942 The Leafhoppers of Minnesota Homoptera: Cicadellidae JOHN T. MEDLER Division of Entomology and Economic Zoology University of Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station The Leafhoppers of Minnesota Homoptera: Cicadellidae JOHN T. MEDLER Division of Entomology and Economic Zoology University of Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station Accepted for publication June 19, 1942 CONTENTS Page Introduction 3 Acknowledgments 3 Sources of material 4 Systematic treatment 4 Eurymelinae 6 Macropsinae 12 Agalliinae 22 Bythoscopinae 25 Penthimiinae 26 Gyponinae 26 Ledrinae 31 Amblycephalinae 31 Evacanthinae 37 Aphrodinae 38 Dorydiinae 40 Jassinae 43 Athysaninae 43 Balcluthinae 120 Cicadellinae 122 Literature cited 163 Plates 171 Index of plant names 190 Index of leafhopper names 190 2M-6-42 The Leafhoppers of Minnesota John T. Medler INTRODUCTION HIS bulletin attempts to present as accurate and complete a T guide to the leafhoppers of Minnesota as possible within the limits of the material available for study. It is realized that cer- tain groups could not be treated completely because of the lack of available material. Nevertheless, it is hoped that in its present form this treatise will serve as a convenient and useful manual for the systematic and economic worker concerned with the forms of the upper Mississippi Valley. In all cases a reference to the original description of the species and genus is given. Keys are included for the separation of species, genera, and supergeneric groups. In addition to the keys a brief diagnostic description of the important characters of each species is given. Extended descriptions or long lists of references have been omitted since citations to this literature are available from other sources if ac- tually needed (Van Duzee, 1917). -

Lichens and Associated Fungi from Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska

The Lichenologist (2020), 52,61–181 doi:10.1017/S0024282920000079 Standard Paper Lichens and associated fungi from Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska Toby Spribille1,2,3 , Alan M. Fryday4 , Sergio Pérez-Ortega5 , Måns Svensson6, Tor Tønsberg7, Stefan Ekman6 , Håkon Holien8,9, Philipp Resl10 , Kevin Schneider11, Edith Stabentheiner2, Holger Thüs12,13 , Jan Vondrák14,15 and Lewis Sharman16 1Department of Biological Sciences, CW405, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2R3, Canada; 2Department of Plant Sciences, Institute of Biology, University of Graz, NAWI Graz, Holteigasse 6, 8010 Graz, Austria; 3Division of Biological Sciences, University of Montana, 32 Campus Drive, Missoula, Montana 59812, USA; 4Herbarium, Department of Plant Biology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, USA; 5Real Jardín Botánico (CSIC), Departamento de Micología, Calle Claudio Moyano 1, E-28014 Madrid, Spain; 6Museum of Evolution, Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 16, SE-75236 Uppsala, Sweden; 7Department of Natural History, University Museum of Bergen Allégt. 41, P.O. Box 7800, N-5020 Bergen, Norway; 8Faculty of Bioscience and Aquaculture, Nord University, Box 2501, NO-7729 Steinkjer, Norway; 9NTNU University Museum, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway; 10Faculty of Biology, Department I, Systematic Botany and Mycology, University of Munich (LMU), Menzinger Straße 67, 80638 München, Germany; 11Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK; 12Botany Department, State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, Rosenstein 1, 70191 Stuttgart, Germany; 13Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK; 14Institute of Botany of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Zámek 1, 252 43 Průhonice, Czech Republic; 15Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, Branišovská 1760, CZ-370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic and 16Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve, P.O. -

Yorkhill Green Spaces Wildlife Species List

Yorkhill Green Spaces Wildlife Species List April 2021 update Yorkhill Green Spaces Species list Draft list of animals, plants, fungi, mosses and lichens recorded from Yorkhill, Glasgow. Main sites: Yorkhill Park, Overnewton Park and Kelvinhaugh Park (AKA Cherry Park). Other recorded sites: bank of River Kelvin at Bunhouse Rd/ Old Dumbarton Rd, Clyde Expressway path, casual records from streets and gardens in Yorkhill. Species total: 711 Vertebrates: Amhibians:1, Birds: 57, Fish: 7, Mammals (wild): 15 Invertebrates: Amphipods: 1, Ants: 3, Bees: 26, Beetles: 21, Butterflies: 11, Caddisflies: 2, Centipedes: 3, Earthworms: 2, Earwig: 1, Flatworms: 1, Flies: 61, Grasshoppers: 1, Harvestmen: 2, Lacewings: 2, Mayflies: 2, Mites: 4, Millipedes: 3, Moths: 149, True bugs: 13, Slugs & snails: 21, Spiders: 14, Springtails: 2, Wasps: 13, Woodlice: 5 Plants: Flowering plants: 174, Ferns: 5, Grasses: 13, Horsetail: 1, Liverworts: 7, Mosses:17, Trees: 19 Fungi and lichens: Fungi: 24, Lichens: 10 Conservation Status: NameSBL - Scottish Biodiversity List Priority Species Birds of Conservation Concern - Red List, Amber List Last Common name Species Taxon Record Common toad Bufo bufo amphiban 2012 Australian landhopper Arcitalitrus dorrieni amphipod 2021 Black garden ant Lasius niger ant 2020 Red ant Myrmica rubra ant 2021 Red ant Myrmica ruginodis ant 2014 Buff-tailed bumblebee Bombus terrestris bee 2021 Garden bumblebee Bombus hortorum bee 2020 Tree bumblebee Bombus hypnorum bee 2021 Heath bumblebee Bombus jonellus bee 2020 Red-tailed bumblebee Bombus