Misplaced Democracy Ii Misplaced Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative Digital Movies As Malaysian National Cinema A

Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Hsin-ning Chang April 2017 © 2017 Hsin-ning Chang. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema by HSIN-NING CHANG has been approved for Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by Erin Schlumpf Visiting Assistant Professor of Film Studies Elizabeth Sayrs Interim Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT CHANG, HSIN-NING, Ph.D., April 2017, Interdisciplinary Arts Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema Director of dissertation: Erin Schlumpf This dissertation argues that the alternative digital movies that emerged in the early 21st century Malaysia have become a part of the Malaysian national cinema. This group of movies includes independent feature-length films, documentaries, short and experimental films and videos. They closely engage with the unique conditions of Malaysia’s economic development, ethnic relationships, and cultural practices, which together comprise significant understandings of the nationhood of Malaysia. The analyses and discussions of the content and practices of these films allow us not only to recognize the economic, social, and historical circumstances of Malaysia, but we also find how these movies reread and rework the existed imagination of the nation, and then actively contribute in configuring the collective entity of Malaysia. 4 DEDICATION To parents, family, friends, and cats in my life 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Prof. -

Najib's Fork-Tongue Shows Again: Umno Talks of Rejuvenation Yet Oldies Get Plum Jobs at Expense of New Blood

NAJIB'S FORK-TONGUE SHOWS AGAIN: UMNO TALKS OF REJUVENATION YET OLDIES GET PLUM JOBS AT EXPENSE OF NEW BLOOD 11 February 2016 - Malaysia Chronicle The recent appointments of Tan Sri Annuar Musa, 59, as Umno information chief, and Datuk Seri Ahmad Bashah Md Hanipah, 65, as Kedah menteri besar, have raised doubts whether one of the oldest parties in the country is truly committed to rejuvenating itself. The two stalwarts are taking over the duties of younger colleagues, Datuk Ahmad Maslan, 49, and Datuk Seri Mukhriz Mahathir, 51, respectively. Umno’s decision to replace both Ahmad and Mukhriz with older leaders indicates that internal politics trumps the changes it must make to stay relevant among the younger generation. In a party where the Youth chief himself is 40 and sporting a greying beard, Umno president Datuk Seri Najib Razak has time and again stressed the need to rejuvenate itself and attract the young. “Umno and Najib specifically have been saying about it (rejuvenation) for quite some time but they lack the political will to do so,” said Professor Dr Arnold Puyok, a political science lecturer from Universiti Malaysia Sarawak. “I don’t think Najib has totally abandoned the idea of ‘peremajaan Umno’ (rejuvenation). He is just being cautious as doing so will put him in a collision course with the old guards.” In fact, as far back as 2014, Umno Youth chief Khairy Jamaluddin said older Umno leaders were unhappy with Najib’s call for rejuvenation as they believed it would pit them against their younger counterparts. He said the “noble proposal” that would help Umno win elections could be a “ticking time- bomb” instead. -

Download This Report in English

Human Rights Watch July 2004 Vol. 16, No. 9 (B) Help Wanted: Abuses against Female Migrant Domestic Workers in Indonesia and Malaysia Map 1: Map of Southeast Asia...................................................................................................1 Map 2: Migration Flows between Indonesia and Malaysia.................................................... 2 I. Summary.................................................................................................................................... 3 Key Recommendations............................................................................................................7 II. Background............................................................................................................................... 8 Labor Migration in Asia........................................................................................................... 8 Indonesian Migrant Workers in Malaysia............................................................................10 Domestic Work.......................................................................................................................12 Trafficking................................................................................................................................14 Repression of Civil Society in Malaysia: The Irene Fernandez Case ..............................16 The Status of Women and Girls in Indonesia....................................................................17 The Status of Women and Girls in -

Politik Dimalaysia Cidaip Banyak, Dan Disini Sangkat Empat Partai Politik

122 mUah Vol. 1, No.I Agustus 2001 POLITICO-ISLAMIC ISSUES IN MALAYSIA IN 1999 By;Ibrahim Abu Bakar Abstrak Tulisan ini merupakan kajian singkat seJdtar isu politik Islam di Malaysia tahun 1999. Pada Nopember 1999, Malaysia menyelenggarakan pemilihan Federal dan Negara Bagian yang ke-10. Titik berat tulisan ini ada pada beberapa isupolitik Islamyang dipublikasikandi koran-koran Malaysia yang dilihat dari perspektifpartai-partaipolitik serta para pendukmgnya. Partai politik diMalaysia cidaip banyak, dan disini Sangkat empat partai politik yaitu: Organisasi Nasional Malaysia Bersatu (UMNO), Asosiasi Cina Ma laysia (MCA), Partai Islam Se-Malaysia (PMIP atau PAS) dan Partai Aksi Demokratis (DAP). UMNO dan MCA adalah partai yang berperan dalam Barisan Nasional (BA) atau FromNasional (NF). PASdan DAP adalah partai oposisipadaBarisanAltematif(BA) atau FromAltemattf(AF). PAS, UMNO, DAP dan MCA memilikipandangan tersendiri temang isu-isu politik Islam. Adanya isu-isu politik Islam itu pada dasamya tidak bisa dilepaskan dari latar belakang sosio-religius dan historis politik masyarakat Malaysia. ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^^ ^ <•'«oJla 1^*- 4 ^ AjtLtiLl jS"y Smi]?jJI 1.^1 j yLl J J ,5j^I 'jiil tJ Vjillli J 01^. -71 i- -L-Jl cyUiLLl ^ JS3 i^LwSr1/i VjJ V^j' 0' V oljjlj-l PoUtico-Islnndc Issues bi Malays bi 1999 123 A. Preface This paper is a short discussion on politico-Islamic issues in Malaysia in 1999. In November 1999 Malaysia held her tenth federal and state elections. The paper focuses on some of the politico-Islamic issues which were pub lished in the Malaysian newsp^>ers from the perspectives of the political parties and their leaders or supporters. -

With Israel? Malaysiakini.Com 14 Februari 2018 Has Malaysia

Harapan MP: Is Malaysia having ‘an affair’ with Israel? MalaysiaKini.com 14 Februari 2018 Has Malaysia softened its stance on Israel by allowing the latter's high- ranking officials to enter the country, questioned an Amanah lawmaker today. Kuala Terengganu MP Raja Kamarul Bahrin Shah Raja Ahmad in a statement said the government's "unannounced" move had caused shock and sadness amongst many Muslims in the country. "Have we pawned the pride of Muslims in matters concerning Israel just for the sake of money and trade? “Just days after the deputy prime minister sent home 12 Uighur Muslims back to China on the pretext of maintaining "good relations" between the two countries what has become of Muslim dignity and pride in the country?" he asked. Kamarul Bahrin was responding to news reports that a delegation of Israeli diplomats had attended the recent week-long ninth Urban World Forum in Kuala Lumpur. The delegation was reportedly led by David Roet who was formerly Israel's deputy ambassador to the United Nations. Kamarul Bahrin urged Malaysia to state clearly, its current position on Israel. "Is this a product of the wasatiyah concept practised by (Prime Minister) Najib (Abdul Razak) or upon the advice of the 'Global Movement of Moderates' led by Nasaruddin Mat Isa and which had caused the government's change in attitude and policy? The rakyat wants to know. "Or is Najib so eager to follow in the footsteps of the Saudi Arabian government which reportedly has close ties to Israel? Is Malaysia having an 'affair' with Israel'?" he asked. -

SARAWAK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PART II Published by Authority

For Reference Only T H E SARAWAK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PART II Published by Authority Vol. LXXI 25th July, 2016 No. 50 Swk. L. N. 204 THE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS ORDINANCE THE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS ORDER, 2016 (Made under section 3) In exercise of the powers conferred upon the Majlis Mesyuarat Kerajaan Negeri by section 3 of the Administrative Areas Ordinance [Cap. 34], the following Order has been made: Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Administrative Areas Order, 2016, and shall be deemed to have come into force on the 1st day of August, 2015. Administrative Areas 2. Sarawak is divided into the divisions, districts and sub-districts specified and described in the Schedule. Revocation 3. The Administrative Areas Order, 2015 [Swk. L.N. 366/2015] is hereby revokedSarawak. Lawnet For Reference Only 26 SCHEDULE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS KUCHING DIVISION (1) Kuching Division Area (Area=4,195 km² approximately) Commencing from a point on the coast approximately midway between Sungai Tambir Hulu and Sungai Tambir Haji Untong; thence bearing approximately 260º 00′ distance approximately 5.45 kilometres; thence bearing approximately 180º 00′ distance approximately 1.1 kilometres to the junction of Sungai Tanju and Loba Tanju; thence in southeasterly direction along Loba Tanju to its estuary with Batang Samarahan; thence upstream along mid Batang Samarahan for a distance approximately 5.0 kilometres; thence bearing approximately 180º 00′ distance approximately 1.8 kilometres to the midstream of Loba Batu Belat; thence in westerly direction along midstream of Loba Batu Belat to the mouth of Loba Gong; thence in southwesterly direction along the midstream of Loba Gong to a point on its confluence with Sungai Bayor; thence along the midstream of Sungai Bayor going downstream to a point at its confluence with Sungai Kuap; thence upstream along mid Sungai Kuap to a point at its confluence with Sungai Semengoh; thence upstream following the mid Sungai Semengoh to a point at the midstream of Sungai Semengoh and between the middle of survey peg nos. -

Distribution of One-Minute Rain Rate in Malaysia Derived from TRMM Satellite Data

Ann. Geophys., 31, 2013–2022, 2013 Open Access www.ann-geophys.net/31/2013/2013/ Annales doi:10.5194/angeo-31-2013-2013 © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Geophysicae Distribution of one-minute rain rate in Malaysia derived from TRMM satellite data T. V. Omotosho1,2,3, J. S Mandeep2,3, M. Abdullah2,3, and A. T. Adediji2,4 1Department of Physics, College of Science and Technology Covenant University PMB 1023 Ota, Ogun state, Nigeria 2Institute of Space Science, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 UKM, Bangi, Malaysia 3Department of Electrical, Electronic and System Engineering, Faculty of Engineering & Built Environment, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 UKM, Bangi, Malaysia 4Department of Physics Federal University of Technology, Akure Ondo State, Nigeria Correspondence to: T. V. Omotosho ([email protected]) Received: 31 January 2013 – Revised: 13 August 2013 – Accepted: 21 October 2013 – Published: 19 November 2013 Abstract. Total rainfall accumulation, as well as convective 1 Introduction and stratiform rainfall rate data from the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite sensors have been used to derive the thunderstorm ratio and one-minute rainfall rates, There is the need for reliable rainfall rate data for planning and designing of satellite communications systems, manage- R0.01, for 57 stations in Malaysia for exceedance probabili- ties of 0.001–1 % for an average year, for the period 1998– ment of water resources, agricultural purpose, and flooding, 2010. The results of the rain accumulations from the TRMM as well as to assess the impact of climate change. Rain gauge satellite were validated with the data collected from differ- measurement networks are not as dense or evenly spaced in ent ground data sources from the National Oceanic and At- Malaysia as in other countries, such as the USA, Europe, mospheric Administration (NOAA) global summary of the and Japan. -

Malaysia's China Policy in the Post-Mahathir

The RSIS Working Paper series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed are entirely the author’s own and not that of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. If you have any comments, please send them to the following email address: [email protected] Unsubscribing If you no longer want to receive RSIS Working Papers, please click on “Unsubscribe.” to be removed from the list. No. 244 Malaysia’s China Policy in the Post-Mahathir Era: A Neoclassical Realist Explanation KUIK Cheng-Chwee S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Singapore 30 July 2012 About RSIS The S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) was established in January 2007 as an autonomous School within the Nanyang Technological University. Known earlier as the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies when it was established in July 1996, RSIS’ mission is to be a leading research and graduate teaching institution in strategic and international affairs in the Asia Pacific. To accomplish this mission, it will: Provide a rigorous professional graduate education with a strong practical emphasis, Conduct policy-relevant research in defence, national security, international relations, strategic studies and diplomacy, Foster a global network of like-minded professional schools. GRADUATE EDUCATION IN INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS RSIS offers a challenging graduate education in international affairs, taught by an international faculty of leading thinkers and practitioners. The Master of Science (M.Sc.) degree programmes in Strategic Studies, International Relations and International Political Economy are distinguished by their focus on the Asia Pacific, the professional practice of international affairs, and the cultivation of academic depth. -

DR MAHATHIR BERLEPAS KE ASIA TENGAH (Bernama 15/07/1996)

15 JUL 1996 DR MAHATHIR BERLEPAS KE ASIA TENGAH KUALA LUMPUR, 15 Julai (Bernama) -- Perdana Menteri Datuk Seri Dr Mahathir Mohamad hari ini berlepas dari sini untuk mengadakan lawatan rasmi ke Republik Kyrgyz dan Republik Kazakhstan di Asia Tengah untuk meningkatkan hubungan dua hala. Dr Mahathir yang diiringi isterinya, Datin Seri Dr Siti Hasmah Mohd Ali, akan berada di Republik Kyrgyz mulai hari ini sehingga Khamis, diikuti lawatan ke Kazakhstan sehingga Sabtu. Delegasi Perdana Menteri termasuk lima menteri kabinet -- Menteri luar Datuk Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, Menteri Kerja Raya Datuk Seri S.Samy Vellu, Menteri Perusahaan Utama Datuk Seri Dr Lim Keng Yaik, Menteri Kebudayaan, Keseniaan dan Pelancongan Datuk Sabbaruddin Chik dan Menteri di Jabatan Perdana Menteri Datuk Dr Abdul Hamid Othman. Turut dalam delegasi itu tiga Menteri Besar -- Tan Sri Wan Mokhtar Ahmad dari Terengganu, Datuk Abdul Ghani Othman (Johor) dan Datuk Seri Shahidan Kassim (Perlis) -- serta Ketua Menteri Melaka Datuk Seri Mohd Zin Abdul Ghani. Delegasi perniagaan dengan 81 anggota yang diketuai Pengerusi dan Ketua Eksekutif Penerbangan Malaysia Tan Sri Tajudin Ramli turut mengiringi Dr Mahathir ke kedua-dua negara. Lawatan Perdana Menteri ke kedua-dua negara itu sebagai memenuhi jemputan Presiden Kyrgyz Askar Akayev yang mengadakan lawatan rasmi ke negara ini pada Julai tahun lepas dan Presiden Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev yang melawat Malaysia pada Mei lepas. Lawatan itu merupakan yang pertama oleh seorang Perdana Menteri Malaysia ke kedua-dua negara itu. -- BERNAMA AZZ WE NMO . -

The Adoption of Industrialised Building System (IBS) Construction in Malaysia: the History, Policies, Experiences and Lesson Learned

The adoption of Industrialised Building System (IBS) construction in Malaysia: The history, policies, experiences and lesson learned Mohd Idrus Din, Noraini Bahri, Mohd Azmi Dzulkifly, Mohd Rizal Norman, Kamarul Anuar Mohamad Kamar *, and Zuhairi Abd Hamid Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB) Malaysia * Corresponding author ([email protected]) Purpose Industry and government in Malaysia coined the term industrialised building system (IBS) to describe the adoption of construction industrialisation, mechanisation, and the use of prefabrication of components in building construction. IBS consists of precast component systems, fabricated steel structures, innovative mould systems, modular block systems, and prefabricated timber structures as construction components. Parts of the building that are repetitive but difficult – and too time consuming and labour intensive to be casted onsite – are designed and detailed as standardised components at the factory and are then brought to the site to be assembled. The construction industry in Malaysia has started to embrace IBS as a method of attaining better construction quality and productivity, reducing risks related to occupational safety and health, alleviating issues for skilled workers and dependency on manual foreign labour, and achieving the ultimate goal of reducing the overall cost of construction. The chronology of IBS-adoption in Malaysia goes back a long way, reaching back to the 1960s, when precast elements were adopted in the building industry to address the problem of an acute housing shortage. However, the introduction of IBS was never sustained beyond this period. As a result of the failure of early closed-fabricated systems, the industry is now avoiding changing its construction method to IBS. Some of the foreign systems that were introduced during the late 1960s and 1970s were also found to be unsuitable in Malaysia’s climate and not very compatible with social practices. -

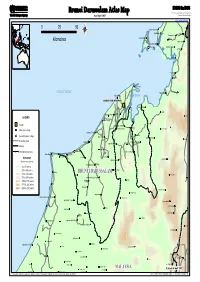

Brunei Darussalam Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section As of April 2007 Division of Operational Services Email : [email protected]

FICSS in DOS Brunei Darussalam Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section As of April 2007 Division of Operational Services Email : [email protected] 0 25 50 Lumat ((( Kampong Lambidan ((( ((( Kpg Manggis ((( ((( Kasaga ((( ((( ((( Kampong Lukut ((( ((( Bea Kpg Ganggarak ((( ((( Bentuka kilometres ((( Padas Valley ((( Kpg Menumbok ((( ((( !! Victoria Kampong Suasa ((( Lumadan ((( Weston ((( Brunei_Darussalam_Atlas_A3LC.WOR Mesapol ((( ((( Sipitang ((( Pekan Muara ((( PACIFIC OCEAN Kpg Banting ((( Malaman Kpg Jerudong Sungai Brunei ((( BANDARBANDAR SERISERI BEGAWANBEGAWAN ( Sundar Bazaar ((( ((( Lawas ((( Kampong Kopang (((Kpg Kilanas ((( LEGEND ((( ((( Ulu Bole ((( Pekan Tutong Trusan ((( Capital Kampong Gadong ((( ((( ((( Limbang ((( ((( Kampong Limau Manis ((( Kampong Belu !! Main town / village Kampong Telamba ((( ((( ((( Bangar Secondary town / village Kpg K Abang ((( Kpg Kuala Bnwan ((( ((( Meligan ((( Secondary road Kpg Lumut ((( Kampong Baru Baru ((( ((( Kpg Batu Danau ((( Bakol Railway ((( Bang Tangur ( !! ((( International boundary !! Pekan Seria Kpg Lepong Lama ((( ((( Kuala Baram ((( Kuala Belait ((( ((( Kampong Rentis ((( Bukit Puan ((( Kpg Medit ELEVATION Long Lutok ((( Kampong Ukong ((( (Above mean sea level) Kampong Sawah ((( 0 to 250 metres 250 to 500 metres ((( Rumah Supon ((( Lutong BRUNEIBRUNEI DARUSSALAMDARUSSALAM 500 to 750 metres ((( ((( Belait ((( ((( Pa Berayong ((( 750 to 1000 metres Kampong Kerangan Nyatan ((( ((( L ((( Bandau 1000 to 1750 metres Kpg Labi ((( 1750 to 2500 metres ((( Miri -

JFKL Publication 11-01.Eps

Past, Present and Future: The 30th Anniversary of the Japan Foundation, Kuala Lumpur Greetings from the Director The Japan Foundation was established in 1972 with the main goal of cultivating friendship and ties between Japan and the world through culture, language, and dialogue. The Kuala Lumpur ofice known as The Japan Foundation Kuala Lumpur Liaison Ofice was established at Wisma Nusantara, off Jalan P. Ramlee on 3 October 1989 as the third liaison ofice in SEA countries, following Jakarta and Bangkok. The liaison ofice was upgraded to Japan Cultural Centre Kuala Lumpur with Prince Takamado attending the opening ceremony on 14 February 1992. Japanese Language Centre Kuala Lumpur was then opened at Wisma Nusantara on 20 April 1995. In July 1998, the ofice moved to Menara Citibank, Jalan Ampang and then once more to our current ofice in Northpoint, Mid-Valley in September 2008. Since the establishment, the Japan Foundation, Kuala Lumpur (JFKL) has been working on various projects such as introducing Japanese arts and culture to Malaysia and vice versa. JFKL has also closely worked with the Ministry of Education to form a solid foundation of Japanese Language Education especially in Malaysian secondary schools and conducted various seminars and trainings for local Japanese teachers. We have also been supporting Japanese studies and promoting dialogues on common international issues. The past 30 years have deinitely been a long yet memorable journey in bringing the cultures of the two countries together. The cultural exchange with Malaysia has become more signiicant and crucial as Japan heads towards a multi-cultural society and there is a lot to learn from Malaysia.