CPY Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 Of.Tif

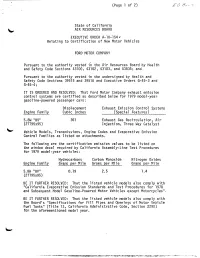

(Page 1 of 2) EO BEST State of California AIR RESOURCES BOARD EXECUTIVE ORDER A-10-154 . Relating to Certification of New Motor Vehicles FORD MOTOR COMPANY Pursuant to the authority vested in the Air Resources Board by Health and Safety Code Sections 43100, 43102, 43103, and 43835; and Pursuant to the authority vested in the undersigned by Health and Safety Code Sections 39515 and 39516 and Executive Orders G-45-3 and G-45-4; IT IS ORDERED AND RESOLVED: That Ford Motor Company exhaust emission control systems are certified as described below for 1979 model-year gasoline-powered passenger cars : Displacement Exhaust Emission Control Systems Engine Family Cubic Inches (Special Features 5. 8W "BV" 351 Exhaust Gas Recirculation, Air (2TT95x95) Injection, Three Way Catalyst Vehicle Models, Transmissions, Engine Codes and Evaporative Emission Control Families as listed on attachments. The following are the certification emission values to be listed on the window decal required by California Assembly-Line Test Procedures for 1979 model-year vehicles : Hydrocarbons Carbon Monoxide Nitrogen Oxides Engine Family Grams per Mile Grams per Mile Grams per Mile 5. 8W "BV" 0. 19 2.5 1.4 (2TT95x95) BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED: That the listed vehicle models also comply with "California Evaporative Emission Standards and Test Procedures for 1978 and Subsequent Model Gasoline-Powered Motor Vehicles except Motorcycles". BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED: That the listed vehicle models also comply with the Board's "Specifications for Fill Pipes and Openings of Motor Vehicle Fuel Tanks" (Title 13, California Administrative Code, Section 2290) for the aforementioned model year. -

Ford/Jeep/Lincoln/Mercury 1975-2000 99-5510

Installation instructions for 99-5510 APPLICATIONS See application list inside WIRING & ANTENNA CONNECTIONS (sold separately) Ford/Jeep/Lincoln/Mercury 1975-2000 Wiring Harness: 99-5510 • 70-1002 • 70-1770 KIT FEATURES • 70-1772 • DIN radio provision • 70-1781 Antenna Adapter: • Not required KIT COMPONENTS TOOLS REQUIRED • A) Radio housing • B) Rounded faceplate • C) Cornered faceplate • D) Rear support • E) Bracket set #1 • Phillips screwdriver • Cutting tool • F) Bracket set #2 • G) Spacer set #1 • H) Spacer set #2 • I) (4)) #8 x 1” Phillips screws • 86-5618 Radio removal keys A B C D CAUTION: Metra recommends disconnecting the negative battery terminal before beginning any installation. All accessories, switches, and especially E F G H I air bag indicator lights must be plugged in before reconnecting the battery or cycling the ignition. NOTE: Refer to the instructions included with the REV. 10/9/2014 INST99-5510 REV. aftermarket radio. METRA. The World’s best kits.™ 1-800-221-0932 metraonline.com © COPYRIGHT 2004-2014 METRA ELECTRONICS CORPORATION 99-5510 Applications AMC Ford (continued) Mercury Alliance................................................................. 1983-1987 Taurus .................................................................. 1990-1995 Capri XR2 ............................................................. 1991-1994 Encore .................................................................. 1983-1987 Taurus .................................................................. 1986-1989 Cougar ................................................................. -

Downfall of Ford in the 70'S

Downfall of Ford in the 70’s Interviewer: Alex Casasola Interviewee: Vincent Sheehy Instructor: Alex Haight Date: February 13, 2013 Table of Contents Interviewee Release Form 3 Interviewer Release Form 4 Statement of Purpose 5 Biography 6 Historical Contextualization 7 Interview Transcription 15 Interview Analysis 35 Appendix 39 Works Consulted 41 Statement of Purpose The purpose of this project was to divulge into the topic of Ford Motor Company and the issues that it faced in the 1970’s through Oral History. Its purpose was to dig deeper into that facts as to why Ford was doing poorly during the 1970’s and not in others times through the use of historical resources and through an interview of someone who experienced these events. Biography Vincent Sheehy was born in Washington DC in 1928. Throughout his life he has lived in the Washington DC and today he resides in Virginia. After graduating from Gonzaga High School he went to Catholic University for college and got a BA in psychology. His father offered him a job into the car business, which was the best offer available to him at the time. He started out a grease rack mechanic and did every job in the store at the Ford on Georgia Ave in the 50’s. He worked as a mechanic in the parts department and became a owner until he handed down the dealership to his kids. He got married to his wife in 1954 and currently has 5 kids. He is interested in golf, skiing and music. When he was younger he participated in the Board of Washington Opera. -

Weaverville Garage Estate Liquidation

10/02/21 11:23:51 Weaverville Garage Estate Liquidation Auction Opens: Sat, Dec 3 12:00am PT Auction Closes: Wed, Dec 7 10:00am PT Lot Title Lot Title 1099 1953 MG TD Sports Car Convertible 1134 Trunk Lid For Mid 60's Mercury Meteor 1100 1969 Oldsmobile Toronado 1135 50's Dodge Pickup Hood 1101 1970 Pontiac Lemans Hardtop 1136 Full-Size Chevrolet Bumpers 1102 Early 50's GMC 300 School Bus 1137 1969-1970 Mustang Mach I/Fastback Trunk Lid 1103 1974 Chevrolet Vega Station Wagon 1138 Chevrolet Vega Hatchback Door 1104 1974 Mercedes 450SL 1139 Set of 1961 Chevrolet Station Wagon Doors 1105 1978 Chevrolet El Camino 1140 Late 60's/Early 70's Buick Sedan Right-Side 1106 1951 Hudson Pacemaker Doors 1107 1972 Pontiac Ventura Sprint 1141 1964 Chevrolet Hardtop Doors 1108 1961 Corvair 500 Lakewood Station Wagon 1142 1964 Ford Galaxie Drivers Door 1109 1966 Dodge Sportsman Van 1143 1971-1972 Ford LTD Passenger Door 1110 1968/ 1969 Dodge Coronet 440 1144 Set of 1960 Ford Ranch Wagon Doors 1111 1974 Ford Maverick Grabber 1145 1970-1971 Ford Torino Drivers Door Fairlane 1112 2 each International Scout AWD 1146 1961-1962 Chevrolet Station Wagon Rear Passenger Door 1114 1968/1969 Chevrolet Malibu 4-Door Hardtop 1147 1970-1971 Ford Torino Drivers Door Fairlane 1115 1970 Volkswagen Beetle With Sunroof 1148 1969 Mustang Passenger Door 1116 1974 Plymouth Satellite Sebring Plus 1149 Set of Full Size Chevrolet Hardtop Doors 1117 1967 Chevrolet Caprice Station Wagon 1150 Postwar Truck Tri-Fold Pickup Hood 1118 Pair of Studebaker Lark 2-Door Sedans 1151 1949-1951 -

2013-Carlisle-Ford-Nationals

OFFICIAL EVENT DIRECTORY OFFICIAL DIRECTORY PARTNER VISIT BUILDING T FOR YOUR EVENT SHIRTS AT THE CARLISLE STORE WELCOME KEN APPELL, EVENT MANAGER 1970 GRABBER ORANGE BOSS 302 — IT COMMANDS ATTENTION ’d like to personally welcome you to the 2013 edition elcome to the largest all-Ford event in the world. Iof the Carlisle Ford Nationals and want to thank each WFrom show-quality F-150s to Shelby GT350s, and every one of you for supporting us this year and from parts at the swap meet to complete cars for sale for many returning attendees. Like many of you here in the car corral, it’s all here this weekend. this weekend I’ve attended this event almost every year While the cars here represent a broad spectrum of since the early 2000s. I am particularly honored to be interests, including Lincoln/Mercury and European able to step into the role of Event Manager at a time Ford alongside First-gen Mustangs and F-series that the car market is ever-changing. trucks, everyone here shares the same passion for the Th roughout the weekend, I hope you take the time brand. And if you look back, I’m willing to bet you to to visit the unique displays and celebrations. First, can pinpoint the moment that sparked that passion for take a look at the 50th Anniversary of the HiPo 289 in you. Building G. Th ere are some really unique Mustangs, For me, that moment was in 2001, when a Grabber Fairlanes and a few other HiPo 289-powered vehicles Orange ’70 Boss 302 came into the small auto that are a real treat to see, including Milo Coleman’s repair shop where I worked. -

Car Wars 2020-2023 the Rise (And Fall) of the Crossover?

The US Automotive Product Pipeline Car Wars 2020-2023 The Rise (and Fall) of the Crossover? Equity | 10 May 2019 Car Wars thesis and investment relevance Car Wars is an annual proprietary study that assesses the relative strength of each automaker’s product pipeline in the US. The purpose is to quantify industry product trends, and then relate our findings to investment decisions. Our thesis is fairly straightforward: we believe replacement rate drives showroom age, which drives market United States Autos/Car Manufacturers share, which drives profits and stock prices. OEMs with the highest replacement rate and youngest showroom age have generally gained share from model years 2004-19. John Murphy, CFA Research Analyst Ten key findings of our study MLPF&S +1 646 855 2025 1. Product activity remains reasonably robust across the industry, but the ramp into a [email protected] softening market will likely drive overcrowding and profit pressure. Aileen Smith Research Analyst 2. New vehicle introductions are 70% CUVs and Light Trucks, and just 24% Small and MLPF&S Mid/Large Cars. The material CUV overweight (45%) will likely pressure the +1 646 743 2007 [email protected] segment’s profitability to the low of passenger cars, and/or will leave dealers with a Yarden Amsalem dearth of entry level product to offer, further increasing an emphasis on used cars. Research Analyst MLPF&S 3. Product cadence overall continues to converge, making the market increasingly [email protected] competitive, which should drive incremental profit pressure across the value chain. Gwen Yucong Shi 4. -

Record Group 48: Ford Village Industries 1926-2002 1 Manuscript Box, 1 Half Manuscript Box, 3 Binders

Record Group 48: Ford Village Industries 1926-2002 1 manuscript box, 1 half manuscript box, 3 binders Plymouth Historical Museum, Plymouth, MI Finding Aid Written by Elizabeth Kelley Kerstens, 17 August 2006 Updated by Paige Wojcik, 22 June 2011 Updated by Jennifer Meekhof, 14 December 2011 Creator: Ford Village Industries Acquisition: The Ford Village Industries records were deposited in the archives at various dates from 1981-2005 Language: Materials in English Access: Records are open for research Use: Refer to Archives Reading Room Guidelines Notes: Citation Style: ―Ford Village Industries,‖ Record Group 48, Archives, Plymouth Historical Museum Abstract Henry Ford created 19 different ―Village Industries‖ of small industrial centers in rural areas of Michigan; over 30 villages total in the country. These centers were intended to prevent disruption of rural living, but unite the lifestyle with factory working. Henry Ford developed the Village Industries program in an attempt to provide a stable the income flow of farm workers during the winter. All of the villages were on the banks of rivers, often on the sites of abandoned gristmills with waterwheels. The Plymouth village industry is located at 230 Wilcox in Plymouth, Michigan. It was originally a flour mill built in 1845 by Henry Holbrook that later became Wilcox Mills. Wilcox Mills operated as a gristmill until Henry Ford purchased it. The village industry opened in 1923 and employed up to 23 people making taps and other tools used in manufacturing. The village closed in 1948, but designated a state of Michigan historic site in 1989. Scope and Content The Ford Village Industries record group contains information about the Village Industry in Plymouth MI as well as some additional information of the ford motor company and Henry Ford, as related to the Village Industries. -

A Microeconomic Analysis of the Full-Size Automobile Market

A Microeconomic Analysis of the Full-Size Automobile Market Jeffrey Thomas Shepherd Lipschultz University of Nebraska at Omaha The author, an undergraduate student at The University of Nebraska at Omaha, would like to acknowledge in deepest gratitude the following persons whose support made this study possible: Dr. William Corcoran, Alexandra Lipschultz, Elizabeth Lipschultz, Dr. Jeremy Lipschultz, Janet Pol, Rosalie Saltzman, James Shaw, Faye Shepherd, Michelle Tai, and Erica Tesla. Introduction The automobile production industry in the United States is in a clear state of turmoil, particularly in the case of domestically owned firms. Sharon Silke Carty attributed problems in the industry, one example being the bankruptcy of parts supplier and former General Motors holding Delphi, to “escalating raw material prices, reduced automaker production and soaring benefits and labor costs.” According to Carty, this bankruptcy did not bode well for GM, itself in beleaguered condition.1 The other remaining domestically owned automobile production firm at the time of the collection of the data presented herein,2 the Ford Motor Company, is also in poor condition; Dorinda Elliott attributed the companies’ weak positions to successful foreign competition.3 Ford and GM have responded to their often-unprofitable conditions by employee and output cuts. Ford, as an example, reduced output by 21% in the fourth quarter of 2006.4 At 1 Sharon Silke Carty, “Analyst: Delphi's Chapter 11 filing pushes GM closer to brink,” USA Today, October 11, 2005. 2 On May 14, 2007, the US-based private equity firm Cerberus purchased an 80% holding in Chrysler Group from the German DaimlerChrysler conglomerate, the product of a 1998 acquisition of Chrysler Corp. -

Melvin's 2017 Maverick / Comet Catalog

MELVIN’S CLASSIC FORD PARTS We sell only the best available! About the Cover Paul's 1971 Maverick Grabber was purchased from the 2nd owner in 2012 with just over 19,000 original miles on the odometer. After shipping the car over 1,200 miles to Canada and driving the car for a few weeks, it was discovered that the cowl area required replacing. From Jan 2013 until June 2016, the car was completely dismantled, the cowl was replaced and engine bay and interior were freshened-up, along with adding 5-lug disc brakes and Factory Aluminum Slots to all four corners. The car still wears 90% of its original Grabber Yellow exterior paint. Paul restored/built this car in memory of his late father, who was responsible for getting Paul interested in Mavericks and Comets at the age of 14. The Grabber now serves as a memory-maker for Paul, his wife and their two children. MELVIN'S CLASSIC FORD PARTS Mustang | Falcon | Galaxie | Truck | Model A | Street Mod | 1932-59 Cars | Thunderbird | Fairlane | Maverick Dear Maverick and Comet owners, Well, the time has come for us to face the music and retire. You will all be glad to hear that Melvin's Classic Ford Parts will continue under the capable hands of Randy, our youngest son. Most of you will remember him starting out with us when he was 12 years old and we had to drag him to car shows. How time flies when you are having fun! He worked with us from 1993 until 2011 and now he is back. -

Classic Heater Cores (HTR)

Classic All-Metal Heater Cores Designed to outlast and outperform the competition! Features include: V-Cell construction; collared-in, brazed-pipe connection that provides maximum strength to prevent pipe-to-tank leakage; extensive coverage for classic cars and trucks; made in North America. Part Number Description 0390306 90-97 FORD LN7000, LN8000, LN9000, L9000 LOUISVILLE 0394152 71-78 CHYRSLER, DODGE, PLYMOUTH CORDOBA, CHARGER, FURY 0394155 67-70 FORD FAIRLANE, MERCURY COMET Part Number Description 0394156 69-70 BUICK RIVIERA, CADILLAC DEVILLE, ELDORADO, OLDS TORONADO 0398218 69-76 CHEVROLET BELAIR, CAPRICE, IMPALA, CADILLAC FLEETWOOD 0394157 69-70 BUICK ELECTRA, WILDCAT, OLDSMOBILE 98, DELTA 88 0398219 71-87 CHEVROLET BELAIR, RIVIERA, IMPALA, OLDS 98 0394158 77-78 FORD CUSTOM 500. LTD, LINCOLN CONTINENTAL, MERCURY GRAND MARQUIS 0398221 82-94 CHEVROLET/GMC S10, S10 BLAZER, S15, S15 BLAZER BRAVADA 0394162 60-63 CHEVROLET GMC C/K SERIES SUBURBAN 0398222 69-74 CHEVROLET CAMARO, NOVA, FIREBIRD, VENTURA 0394171 75-93 VOLVO 240 - 265 SERIES 0398223 GM HEATER - NO INFO FOUND IN COMPUTER 0394186 98-03 FORD ESCORT 0398224 64-66 CHEVROLET/GMC C/K P SERIES, SUBURBAN 0394188 FORD HEATER - NO OTHER INFO FOUND 0398226 67-72 CHEVROLET BELAIR, IMPALA, GTO, LEMANS, SKYLARK 0398006 85-91 FORD ECONOLINE & CLUB WAGON 0398228 71-81 CHEVROLET CAMARO, NOVA, FIREBIRD, VENTURA 0398009 65-67 FORD CUSTOM 500, GALAXIE, LTD MONTEREY 0398229 67-72 CHEVROLET CHEVELLE, EL CAMINO, MONTE CARLO, GRAND PRIX 0398012 68 FORD COUNTRY SEDAN, GALAXIE 500 LTD MARQUIS 0398230 -

DASH4 BUYERS GUIDE RIVETED SHOES.Xlsx

PART LOCATION APPLICATION NUMBER 57‐52 BUICK ROADMASTER, 68‐65 CADILLAC CALAIS, 68‐61 CADILLAC DEVILLE, 66‐60 CADILLAC EL DORADO, 68‐61 CADILLAC R127 REAR FLEETWOOD, 72‐69 CHEVROLET C20, 70‐69 CHEVROLET TRUCK P20 66‐62 DODGE Dart, Demon Swinger, 68‐62 FORD Fairlane, 83‐78 FORD Fairmont, 68‐63 FORD Falcon, 82‐81 FORD Granada, 86‐83 FORD LTD Mid Size, 77‐71 FORD Maverick, 82‐80 FORD Mustang, 73‐64 FORD Mustang, 88‐81 FORD Thunderbird, 68 FORD Torino, 65‐60 FORD TRUCK Ranchero, 67‐64 MERCURY Caliente, 82‐80 MERCURY Capri RWD, 63‐62 MERCURY Colony Park, 77‐74 R151 REAR MERCURY Comet, 72‐71 MERCURY Comet, 67‐63 MERCURY Comet, 88‐81 MERCURY Cougar, 69‐67 MERCURY Cougar, 63 MERCURY Country Cruiser, 63 MERCURY Marauder, 86‐83 MERCURY Marquis,Meteor, 63 MERCURY Meteor, 68 MERCURY Montego, 63 MERCURY Monterey, 83‐78 MERCURY Zephyr, 66‐65 PLYMOUTH Valiant 68‐62 DODGE Dart, Demon Swinger, 54‐51 FORD Country Squire, 54‐50 FORD Crestline, 52‐50 FORD Custom, 54‐52 FORD Customline, 51‐50 FORD Deluxe, 70‐69 FORD Fairlane, 66‐62 FORD Fairlane, 70‐63 FORD Falcon, 54‐52 FORD Mainline, 71 FORD Maverick, 71‐64 FORD Mustang, 54 FORD Skyliner, 54‐52 FORD Sunliner, 71‐69 FORD Torino, 54‐51 FORD Victoria, 65‐60 FORD R154 FRONT TRUCK Ranchero, 55 HUDSON Wasp, 67‐64 MERCURY Caliente, 63‐62 MERCURY Colony Park, 71 MERCURY Comet, 67‐63 MERCURY Comet, 70‐67 MERCURY Cougar, 63 MERCURY Country Cruiser, 63 MERCURY Marauder, 63 MERCURY Meteor, 71‐69 MERCURY Montego, 63 MERCURY Monterey, 68‐65 PLYMOUTH Valiant R155 USE R169 USE R169 78 AMC AMX, 74‐73 AMC AMX, 71‐70 AMC -

DASH4 BUYERS GUIDE BONDED SUPER SHOES WEB.Xlsx

PART LOCATION APPLICATION NUMBER SB9 USE SB55 63‐60 CHEVROLET/GMC TRUCK K2500, 81‐78 DODGE TRUCK B350, 81‐57 DODGE TRUCK D250, 79‐78 DODGE TRUCK D350, 71‐55 DODGE TRUCK D350, 71‐56 DODGE TRUCK M300, 74‐60 DODGE TRUCK P200, 71‐59 DODGE TRUCK P300, 68‐57 DODGE TRUCK W150, 81‐78 DODGE TRUCK W250, 74‐57 DODGE TRUCK W250, 81‐78 DODGE TRUCK W350, 76‐51 FORD TRUCK F250, 66‐51 FORD TRUCK F350, 76‐53 FORD TRUCK P350, 72‐65 IHC TRUCK 1000C, 72‐65 IHC TRUCK 1100B, 72‐65 IHC TRUCK 1100C, 72‐65 IHC TRUCK SB33 REAR 1200A, 72‐65 IHC TRUCK 1200B, 72‐65 IHC TRUCK 1200C, 72‐65 IHC TRUCK 1300A, 72‐70 IHC TRUCK 1300B, 68‐65 IHC TRUCK 1300B, 72‐65 IHC TRUCK 1300C, 68‐67 IHC TRUCK 1500A, 68‐67 IHC TRUCK 1500B, 68‐61 IHC TRUCK 1500C, 68‐61 IHC TRUCK 1500D, 68‐65 IHC TRUCK 900 Series, 59 IHC TRUCK B130, 59 IHC TRUCK B132, 65‐61 IHC TRUCK C & D, 73‐61 IHC TRUCK Metro, 73‐72 JEEP TRUCK FJ Series, 73‐72 JEEP TRUCK Gladiator, 81‐78 PLYMOUTH TRUCK PB350 58‐53 CHEVROLET Bel Air, 58 CHEVROLET Biscayne, 58 CHEVROLET Brookwood, 62‐53 CHEVROLET Corvette, 52‐51 CHEVROLET De Luxe, 58 CHEVROLET Delray, 57‐53 CHEVROLET One Fifty, 52‐51 CHEVROLET Special, 57‐53 CHEVROLET Two Ten, 58‐51 CHEVROLET/GMC TRUCK C1500, 59‐53 CHEVROLET/GMC TRUCK C2500, 59‐53 CHEVROLET/GMC TRUCK K2500, 58 FORD 300, 58 FORD 500, 58‐50 FORD Country Squire, 54‐51 FORD Crestline, 57 FORD Custom, 52‐51 FORD Custom, 49 FORD Custom, 59‐57 FORD Custom 300, 56‐52 FORD Customline, 51‐49 FORD Deluxe, 59‐55 FORD Fairlane, 59 FORD Galaxie, 56‐52 FORD Mainline, 54‐50 FORD SB55 REAR Ranch Wagon, 59‐54 FORD Skyliner,