The Subordinate Integration of Palestinian Arabs Into Israeli Society, 1948-1967

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Practices of Irrigation Water Pricing

\J4S ILI(QQ POLICY RESEARCH WORKING PAPER 1460 Public Disclosure Authorized Efficiency and Equity Pricing of water may affect allocation considerations by Considerations in Pricing users. Efficiency isattainable andAllocating Irrigation wheneverthe pricing method affectsthe demandfor Public Disclosure Authorized Water irrigation water. The extent to which water pricing methods can affect income Yacov Tsur redistributionis limited.To Ariel Dinar affect incomeinequality, a water pricing method must include certain forms of water quantity restrictions. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The WorldBank Agricultureand Natural ResourcesDepartment Agricultural Policies Division May 1995 POLICYRESEARCH WORKING PAPER 1460 Summary findings Economic efficiency has to do with how much wealth a inefficient allocation. But they are usually easier to given resource base can generate. Equity has to do with implement and administer and require less information. how that wealth is to be distributed in society. Economic The extent to which water pricing methods can effect efficiency gets far more attention, in part because equity income redistribution is limited, the authors conclude. considerations involve value judgments that vary from Disparities in farm income are mainly the result of person to person. factors such as farm size and location and soil quality, Tsur and Dinar examine both the efficiency and the but not water (or other input) prices. Pricing schemes equity of different methods of pricing irrigation water. that do not involve quantity quotas cannot be used in After describing water pricing practices in a number of policies aimed at affecting income inequality. countries, they evaluate their efficiency and equity. The results somewhat support the view that water In general they find that water use is most efficient prices should not be used to effect income redistribution when pricing affects the demand for water. -

Pdf, 366.38 Kb

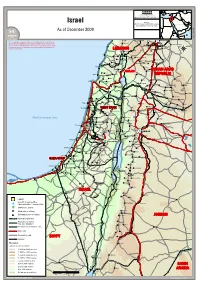

FF II CC SS SS Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services Israel Sources: UNHCR, Global Insight digital mapping © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd. As of December 2009 Israel_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Dahr al Ahmar Jarba The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the 'Aramtah Ma'adamiet Shih Harran al 'Awamid Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, Qatana Haouch Blass 'Artuz territory, city or area of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its Najha frontiers or boundaries LEBANON Al Kiswah Che'baâ Douaïr Al Khiyam Metulla Sa`sa` ((( Kafr Dunin Misgav 'Am Jubbata al Khashab ((( Qiryat Shemons Chakra Khan ar Rinbah Ghabaqhib Rshaf Timarus Bent Jbail((( Al Qunaytirah Djébab Nahariyya El Harra ((( Dalton An Namir SYRIAN ARAB Jacem Hatzor GOLANGOLAN Abu-Senan GOLANGOLAN Ar Rama Acre ((( Boutaiha REPUBLIC Bi'nah Sahrin Tamra Shahba Tasil Ash Shaykh Miskin ((( Kefar Hittim Bet Haifa ((( ((( ((( Qiryat Motzkin ((( ((( Ibta' Lavi Ash Shajarah Dâail Kafr Kanna As Suwayda Ramah Kafar Kama Husifa Ath Tha'lah((( ((( ((( Masada Al Yadudah Oumm Oualad ((( ((( Saïda 'Afula ((( ((( Dar'a Al Harisah ((( El 'Azziya Irbid ((( Al Qrayyah Pardes Hanna Besan Salkhad ((( ((( ((( Ya'bad ((( Janin Hadera ((( Dibbin Gharbiya El-Ne'aime Tisiyah Imtan Hogla Al Manshiyah ((( ((( Kefar Monash El Aânata Netanya ((( WESTWEST BANKBANK WESTWEST BANKBANKTubas 'Anjara Khirbat ash Shawahid Al Qar'a' -

Israel-Hizbullah Conflict: Victims of Rocket Attacks and IDF Casualties July-Aug 2006

My MFA MFA Terrorism Terror from Lebanon Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket attacks and IDF casualties July-Aug 2006 Search Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket E-mail to a friend attacks and IDF casualties Print the article 12 Jul 2006 Add to my bookmarks July-August 2006 Since July 12, 43 Israeli civilians and 118 IDF soldiers have See also MFA newsletter been killed. Hizbullah attacks northern Israel and Israel's response About the Ministry (Note: The figure for civilians includes four who died of heart attacks during rocket attacks.) MFA events Foreign Relations Facts About Israel July 12, 2006 Government - Killed in IDF patrol jeeps: Jerusalem-Capital Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Eyal Benin, 22, of Beersheba Treaties Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Shani Turgeman, 24, of Beit Shean History of Israel Sgt.-Maj. Wassim Nazal, 26, of Yanuah Peace Process - Tank crew hit by mine in Lebanon: Terrorism St.-Sgt. Alexei Kushnirski, 21, of Nes Ziona Anti-Semitism/Holocaust St.-Sgt. Yaniv Bar-on, 20, of Maccabim Israel beyond politics Sgt. Gadi Mosayev, 20, of Akko Sgt. Shlomi Yirmiyahu, 20, of Rishon Lezion Int'l development MFA Publications - Killed trying to retrieve tank crew: Our Bookmarks Sgt. Nimrod Cohen, 19, of Mitzpe Shalem News Archive MFA Library Eyal Benin Shani Turgeman Wassim Nazal Nimrod Cohen Alexei Kushnirski Yaniv Bar-on Gadi Mosayev Shlomi Yirmiyahu July 13, 2006 Two Israelis were killed by Katyusha rockets fired by Hizbullah: Monica Seidman (Lehrer), 40, of Nahariya was killed in her home; Nitzo Rubin, 33, of Safed, was killed while on his way to visit his children. -

Lecturers' Bio Notes

Migration: Educational, Political and Cultural Aspects Beit Berl College 18-19 March 2019 Lecturers’ Bio Notes Steering Committee: Prof. Amos Hofman (Chairperson), Prof. Kussai Haj-Yehia, Dr. Orit Abuhav, Dr. Liat Yakhnich, Dr. Merav Nakar-Sadi, Dr. Adi Binhas, Dr. Ronit Web- man-Shafran, Dr. Saami Mahajna, Anat Benson Note: Bio-notes are listed alphabetically. They are presented as provided by the authors, with only minor editing. Alter, Grit Innsbruck University [email protected] Dr Grit Alter received her Ph.D. from the Münster University (Germany) in 2015. She currently holds a post-doc position at the School of Education/Department of Foreign Language Teacher Education at Innsbruck University (Austria). Her research interests include literature for young readers in foreign language education, CEF-based lit- erary competences, and concepts of cultural learning, textbook analysis, critical media literacy and means of differentiation in ELT. Arar, Khalid Al-Qasemi Academic College of Education [email protected] Prof. Khalid Arar, specializes in research on educational administration, leadership and policy analysis in education and higher education. He conducted studies in the Middle-East, Europe and in North America and in many other cross-national con- texts. His research focuses broadly in equity and diversity in educational leadership and higher education. He serves as associate editor for the International Journal of Leadership (Routledge). Dr. Arar is a board member of International Journal of Educational Management, Higher Education Policy, Journal of Educa- tion Administration & Applied Research in Higher Education. He authored Arab women in management and leadership (2013, Palgrave); Higher Education among the Palestinian Minority in Israel (2016, Pal- grave, with Kussai Haj-Yehia); and edited six different books in Higher Education, Multicultural Educa- tion, and Educational Leadership. -

Aliya Chalutzit from America, 1939-48

1 Aliya of American Pioneers By Yehuda Sela (Silverman) From Hebrew: Arye Malkin A) Aliya1 Attempts During WW II The members of the Ha‟Shomer Ha‟Tzair2 Zionist Youth Movement searched a long time for some means to get to the shores of the Land of Israel (Palestine). They all thought that making Aliya was preferable to joining the Canadian or the American Army, which would possibly have them fighting in some distant war, unrelated to Israel. Some of these efforts seem, in retrospect, unimaginable, or at least naïve. There were a number of discussions on this subject in the Secretariat of Kibbutz Aliya Gimel (hereafter: KAG) and the question raised was whether individual private attempts to make Aliya should be allowed. The problems were quite complicated, and rather than deciding against the effort to make Aliya, it was decided to allow these efforts in special cases. Later on the Secretariat decided against these private individual efforts. The members attempted several ways to pursue this goal, but none were successful. Some applied for a truck driver position with a company that operated in Persia, building roads to connect the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea. Naturally, holding a driving license that did not qualify one for heavy vehicles did not help. Another way was to volunteer to be an ambulance driver in the Middle East, an operation that was being run by the Quakers; this was a pacifist organization that had carried out this sort of work during the First World War. An organization called „The American Field Service‟ recruited its members from the higher levels of society. -

Introduction Really, 'Human Dust'?

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Peck, The Lost Heritage of the Holocaust Survivors, Gesher, 106 (1982) p.107. 2. For 'Herut's' place in this matter, see H. T. Yablonka, 'The Commander of the Yizkor Order, Herut, Shoa and Survivors', in I. Troen and N. Lucas (eds.) Israel the First Decade, New York: SUNY Press, 1995. 3. Heller, On Struggling for Nationhood, p. 66. 4. Z. Mankowitz, Zionism and the Holocaust Survivors; Y. Gutman and A. Drechsler (eds.) She'erit Haplita, 1944-1948. Proceedings of the Sixth Yad Vas hem International Historical Conference, Jerusalem 1991, pp. 189-90. 5. Proudfoot, 'European Refugees', pp. 238-9, 339-41; Grossman, The Exiles, pp. 10-11. 6. Gutman, Jews in Poland, pp. 65-103. 7. Dinnerstein, America and the Survivors, pp. 39-71. 8. Slutsky, Annals of the Haganah, B, p. 1114. 9. Heller The Struggle for the Jewish State, pp. 82-5. 10. Bauer, Survivors; Tsemerion, Holocaust Survivors Press. 11. Mankowitz, op. cit., p. 190. REALLY, 'HUMAN DUST'? 1. Many of the sources posed problems concerning numerical data on immi gration, especially for the months leading up to the end of the British Mandate, January-April 1948, and the first few months of the state, May August 1948. The researchers point out that 7,574 immigrant data cards are missing from the records and believe this to be due to the 'circumstances of the times'. Records are complete from September 1948 onward, and an important population census was held in November 1948. A parallel record ing system conducted by the Jewish Agency, which continued to operate after that of the Mandatory Government, provided us with statistical data for immigration during 1948-9 and made it possible to analyse the part taken by the Holocaust survivors. -

Project Aim and Objectives

1 MICROZONING OF THE EARTHQUAKE HAZARD IN ISRAEL PROJECT 9 SITE SPECIFIC EARTHQUAKE HAZARDS ASSESSMENT USING AMBIENT NOISE MEASUREMENTS IN HADERA, PARDES HANNA, BINYAMINA AND NEIGHBORING SETTLEMENTS November, 2009 Job No 526/473/09 Principal Investigator: Dr. Yuli Zaslavsky Collaborators G. Ataev, M. Gorstein, M. Kalmanovich, D. Giller, I. Dan, N. Perelman, T. Aksinenko, V. Giller, and A. Shvartsburg Submitted to: Earth Sciences Research Administration National Ministry of Infrastructures Contract Number: 28-17-054 2 CONTENT LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................... 4 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 7 Empirical approaches implemented in the analysis of site effect ................................................ 8 GEOLOGICAL OUTLINE ............................................................................................................ 10 Quaternary sediments ................................................................................................................. 12 Tertiary rocks ............................................................................................................................ -

The Audacity of Holiness Orthodox Jewish Women’S Theater עַ זּוּת שֶׁ Israelבִּ קְ Inדוּשָׁ ה

ׁׁ ְִֶַָּּּהבשות שעזּ Reina Rutlinger-Reiner The Audacity of Holiness Orthodox Jewish Women’s Theater ַעזּּו ֶׁת ש in Israelִּבְקּדו ָׁשה Translated by Jeffrey M. Green Cover photography: Avigail Reiner Book design: Bethany Wolfe Published with the support of: Dr. Phyllis Hammer The Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA Talpiot Academic College, Holon, Israel 2014 Contents Introduction 7 Chapter One: The Uniqueness of the Phenomenon 12 The Complexity of Orthodox Jewish Society in Israel 16 Chapter Two: General Survey of the Theater Groups 21 Theater among ultra-Orthodox Women 22 Born-again1 Actresses and Directors in Ultra-Orthodox Society 26 Theater Groups of National-Religious Women 31 The Settlements: The Forge of Orthodox Women’s Theater 38 Orthodox Women’s Theater Groups in the Cities 73 Orthodox Men’s Theater 79 Summary: “Is there such a thing as Orthodox women’s theater?” 80 Chapter Three: “The Right Hand Draws in, the Left Hand Pushes Away”: The Involvement of Rabbis in the Theater 84 Is Innovation Desirable According to the Torah? 84 Judaism and the Theater–a Fertile Stage in the Culture War 87 The Goal: Creation of a Theater “of Our Own” 88 Differences of Opinion 91 Asking the Rabbi: The Women’s Demand for Rabbinical Involvement 94 “Engaged Theater” or “Emasculated Theater”? 96 Developments in the Relations Between the Rabbis and the Artists 98 1 I use this term, which is laden with Christian connotations, with some trepidation. Here it refers to a large and varied group of people who were not brought up as Orthodox Jews but adopted Orthodoxy, often with great intensity, later in life. -

The Absentee Property Law and Its Implementation in East Jerusalem a Legal Guide and Analysis

NORWEGIAN REFUGEE COUNCIL The Absentee Property Law and its Implementation in East Jerusalem A Legal Guide and Analysis May 2013 May 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Consulting legal advisor: Adv. Sami Ershied Language editor: Risa Zoll Hebrew-English translations: Al-Kilani Legal Translation, Training & Management Co. Cover photo: The Cliff Hotel, which was declared “absentee property”, and its owner Ali Ayad. (Photo by: Mohammad Haddad, 2013). This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non-governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Talia Sasson, Adv. Daniel Seidmann and Adv. Raphael Shilhav for their insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 8 2. Background on the Absentee Property Law .................................................. 9 3. Provisions of the Absentee Property Law .................................................... 14 3.1 Definitions .................................................................................................................... -

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005 BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights i BADIL is a member of the Global Palestine Right of Return Coalition Preface The Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons is published annually by BADIL Resource Center. The Survey provides an overview of one of the largest and longest-standing unresolved refugee and displaced populations in the world today. It is estimated that two out of every five of today’s refugees are Palestinian. The Survey has several objectives: (1) It aims to provide basic information about Palestinian displacement – i.e., the circumstances of displacement, the size and characteristics of the refugee and displaced population, as well as the living conditions of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons; (2) It aims to clarify the framework governing protection and assistance for this displaced population; and (3) It sets out the basic principles for crafting durable solutions for Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, consistent with international law, relevant United Nations Resolutions and best practice. In short, the Survey endeavors to address the lack of information or misinformation about Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, and to counter political arguments that suggest that the issue of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons can be resolved outside the realm of international law and practice applicable to all other refugee and displaced populations. The Survey examines the status of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons on a thematic basis. Chapter One provides a short historical background to the root causes of Palestinian mass displacement. -

Regulations and the Rule of Law: a Look at the First Decade of Israel

Keele Law Review, Volume 2 (2021), 45-62 45 ISSN 2732-5679 ‘Hidden’ Regulations and the Rule of Law: A Look at the First decade of Israel Gal Amir* Abstract This article reviews the history of issuing regulations without due promulgation in the first decade of Israel. ‘Covert’ secondary legislation was widely used in two contexts – the ‘austerity policy’ and ‘security’ issues, both contexts intersecting in the state's attitude toward the Palestinian minority, at the time living under military rule. This article will demonstrate that, although analytically the state’s branches were committed to upholding the ‘Rule of Law’, the state used methods of covert legislation, that were in contrast to this principle. I. Introduction Regimes and states like to be associated with the term ‘Rule of Law’, as it is often associated with such terms as ‘democracy’ and ‘human rights’.1 Israel’s Declaration of Independence speaks of a state that will be democratic, egalitarian, and aspiring to the rule of law. Although the term ‘Rule of Law’ in itself is not mentioned in Israel’s Declaration of Independence, the declaration speaks of ‘… the establishment of the elected, regular authorities of the State in accordance with the Constitution which shall be adopted by the Elected Constituent Assembly not later than the 1st October 1948.’2 Even when it became clear, in the early 1950s, that a constitution would not be drafted in the foreseeable future, courts and legislators still spoke of ‘Rule of Law’ as an ideal. Following Rogers Brubaker and Frederick Cooper, one must examine the existence of the rule of law in young Israel as a ‘category of practice’ requiring reference to a citizen's daily experience, detached from the ‘analytical’ definitions of social scientists, or the high rhetoric of legislators and judges.3 Viewing ‘Rule of Law’ as a category of practice finds Israel in the first decades of its existence in a very different place than its legislators and judges aspired to be. -

Stifling Surveillance: Palestinians: Its Goal Has Always Been to Drive Them Out

Israel has never intended to control the Stifling Surveillance: Palestinians: Its goal has always been to drive them out. However, during Israel’s Surveillance the Mandate era, as part of their effort and Control of the to disorganize the Palestinian society, Zionist organizations established various Palestinians during the surveillance bodies to examine and monitor Military Government Era various aspects of Palestinian society. These related to the demographic, religious, Ahmad H. Sa’di tribal, and hamula (extended family or clan) composition of the Palestinians, their spatial distribution, political behaviors, and military capabilities, as well as their resources, chiefly lands and water sources. These activities were part of an all-inclusive effort to establish a Jewish state against the will of the indigenous Arab population. Yet, when the 1948 war ended, Israel leaders found that, contrary to their expectations, a number of Palestinian communities, primarily in the Galilee, had eluded the ethnic cleansing conducted by Jewish forces. The incomplete character of the expulsion of the Palestinians subsequently became subject of much speculation and distortion.1 However, internal discussions among Israeli leaders indicate that the continued presence of these Palestinians within the state of Israel was unintentional and undesired.2 Although a system of political control which relied on the British Defense (Emergency) Regulations was imposed on the Palestinians and a military government to rule them was established already during the war, in addition to various ad hoc practices of surveillance, driving the Palestinians out continued to be Israel’s main objective.3 Although expulsion remained Israel’s favored goal – and various schemes to effect it were contrived during the 1950s and 1960s4 – as early as 1951 Israeli leaders [ 36 ] Stifling Surveillance began realizing that these Palestinians might stay longer than expected.