The Case of the Mining Industry / by Raymond W. Payne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flooding the Border: Development, Politics, and Environmental Controversy in the Canadian-U.S

FLOODING THE BORDER: DEVELOPMENT, POLITICS, AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROVERSY IN THE CANADIAN-U.S. SKAGIT VALLEY by Philip Van Huizen A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) June 2013 © Philip Van Huizen, 2013 Abstract This dissertation is a case study of the 1926 to 1984 High Ross Dam Controversy, one of the longest cross-border disputes between Canada and the United States. The controversy can be divided into two parts. The first, which lasted until the early 1960s, revolved around Seattle’s attempts to build the High Ross Dam and flood nearly twenty kilometres into British Columbia’s Skagit River Valley. British Columbia favoured Seattle’s plan but competing priorities repeatedly delayed the province’s agreement. The city was forced to build a lower, 540-foot version of the Ross Dam instead, to the immense frustration of Seattle officials. British Columbia eventually agreed to let Seattle raise the Ross Dam by 122.5 feet in 1967. Following the agreement, however, activists from Vancouver and Seattle, joined later by the Upper Skagit, Sauk-Suiattle, and Swinomish Tribal Communities in Washington, organized a massive environmental protest against the plan, causing a second phase of controversy that lasted into the 1980s. Canadian and U.S. diplomats and politicians finally resolved the dispute with the 1984 Skagit River Treaty. British Columbia agreed to sell Seattle power produced in other areas of the province, which, ironically, required raising a different dam on the Pend d’Oreille River in exchange for not raising the Ross Dam. -

Premier Bennett to Start Off Running

_ _ o . % IR071IICIAL LIH.~AR¥ P.~RLIAUE.~Ir BLDg. Premier Bennett to start off running Details of the planned, Nothing official is planned with council, the Regional Following the dinner cabinet' before their Alex Fraser, Highways visit of the British Columbia"~ for the party on the 22rid. District, the press and other during which the Premier departure for Terrace. No Minister will be in the Cabinet are more or less However the Premier's day official engagements. The will make a speech, the brlef will be accepted uniess Hazeltons while Don complete. The Premier will will start very early on the only chance the general cabinet will meet in a this procedure has taken Phillips will visit the Prince arrive in Terrace- on the 23rd as he will be jogging public will have to speak regular cabinet session in place. The briefs will be Rupert area, Other 22nd in one of the govern- around the track at Skeena with the Premier wfll be at a the Senior Citizens Room of accepted one by one with a ministers will also. be ment jets. He Will be ac- Junior Secondary School •dinner sponsored by the the Arena Complex. This spokesman allowed to speak making contact in various companied by Provincial getting underway at 6:30 Terrace Centennial Lions meeting is closed to all. It in support of the brief before areas. will get underway at 2 p.m. •the cabinet. For last minute details of Secretary Grace McCarthy, a.m. The Premier invites all between noon and 2 p.m. .... Following the brief the cabinet visit information his Executive Assistant school children and citizens This will be held at the From 3 p.m. -

Debates of the Legislative Assembly

Fourth Session, 40th Parliament OFFICIAL REPORT OF DEBATES OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY (HANSARD) Monday, October 26, 2015 Aft ernoon Sitting Volume 30, Number 2 THE HONOURABLE LINDA REID, SPEAKER ISSN 0709-1281 (Print) ISSN 1499-2175 (Online) PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Entered Confederation July 20, 1871) LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOR Her Honour the Honourable Judith Guichon, OBC Fourth Session, 40th Parliament SPEAKER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Honourable Linda Reid EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Premier and President of the Executive Council ..............................................................................................................Hon. Christy Clark Deputy Premier and Minister of Natural Gas Development and Minister Responsible for Housing ......................Hon. Rich Coleman Minister of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation ......................................................................................................... Hon. John Rustad Minister of Advanced Education ............................................................................................................................... Hon. Andrew Wilkinson Minister of Agriculture ........................................................................................................................................................Hon. Norm Letnick Minister of Children and Family Development .......................................................................................................Hon. Stephanie Cadieux Minister of Community, Sport and Cultural Development -

Educational Policy-Making in British Columbia in the 1970S and 1980S

Let’s Talk about Schools: Educational Policy-Making in British Columbia in the 1970s and 1980s Robert Whiteley he last quarter of the twentieth century is widely seen as a neoliberal age. Rooted in the thought of Austrian Friedrich Hayek and the ideas of Chicago economist Milton Friedman, Tand given purchase through the policies of Ronald Reagan in the United States, Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom, and other politicians elsewhere, neoliberal, or “post liberal” (Fleming 1991), governments align themselves ideologically with the political right. They are typified by centralization of power and financial and regulatory control and anti- union legislation, accelerating fiscally conservative policies that promote the private sector and reduce state involvement in the lives of citizens. Governance in British Columbia in the 1970s and 1980s largely followed this model (Dyck 1986). Through privatization and deregulation, the Social Credit governments that held office through most of these years transferred much control of the province’s economy from the public to the private sector. Accompanying these measures was the neoliberal view that education is a private rather than a public good (Apple 2006). Between the mid-1970s and the rewriting of the School Act in 1989, the funding allocated to education in British Columbia declined both in dollar terms and as a percentage of provincial GDP (Bowman 1990); school boards had little decision-making authority and were increasingly required to follow government dictates. Professor of administration and sometime coordinator of political action at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, Richard G. Tow nsend (1988), characterizes politics in British Columbia’s educational system during the 1970s and 1980s as “discordant” and sees it as mirroring the bipolarity in the province’s political culture. -

The Waffle, the New Democratic Party, and Canada's New Left During the Long Sixties

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-13-2019 1:00 PM 'To Waffleo t the Left:' The Waffle, the New Democratic Party, and Canada's New Left during the Long Sixties David G. Blocker The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Fleming, Keith The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © David G. Blocker 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons Recommended Citation Blocker, David G., "'To Waffleo t the Left:' The Waffle, the New Democratic Party, and Canada's New Left during the Long Sixties" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6554. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6554 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Abstract The Sixties were time of conflict and change in Canada and beyond. Radical social movements and countercultures challenged the conservatism of the preceding decade, rejected traditional forms of politics, and demanded an alternative based on the principles of social justice, individual freedom and an end to oppression on all fronts. Yet in Canada a unique political movement emerged which embraced these principles but proposed that New Left social movements – the student and anti-war movements, the women’s liberation movement and Canadian nationalists – could bring about radical political change not only through street protests and sit-ins, but also through participation in electoral politics. -

Monday, March 3, 1975 Prayers by Capt. J. Foley. Mr. Speaker Gave His

24 Ez. 2 MAC 2 Mnd, Mrh , Two OCOCK .M. Prayers by Capt. l. Mr. Speaker gave his reserved decision on the matter of privilege raised by Mr. Gbn on February 27, 1975, as follows: nrbl Mbr,—h Honourable Member for North Vancouver- Capilano raised as a matter of privilege last Thursday a complaint relating to the disclosure of settlement figures between Public Service Union bargaining units and the Government. He cites the Hon. Provincial Secretary as stating on February 25 to the House in question period: "I intend to adhere to the agreement I have with the union involved not to release the details of settlements until all negotiations are complete." He considers news of disclosure to the public and not to the House to be a breach of privilege of the members and a contempt. There is no evidence from the honourable member that press releases or public statements to the newspapers and media have been made by the Hon. Provincial Secretary. Therefore the fact that the public has become aware before some honourable members of this House does not preclude the information having been received by the Employers' Council of British Columbia by some other simple means. For example, the public may be astute enough to examine existing Orders in Council. Had they done so, certainly the information sought in question period would have been easily discovered. That means, of course, that the Honourable Member for North Vancouver-Capilano could have satisfied his curiosity without the assistance of question period. I have secured most if not all of these Orders in Council for the honourable member. -

The Political Influence of the Individual in Educational Policy-Making

THE POLITICAL INFLUENCE OF THE INDIVIDUAL IN EDUCATIONAL POLICY-MAKING: MECASE OF THE INDEPENDENT SCHOOL ACT by Graeme Stuart Waymark A THESIS SUBMIlTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS (EDUCATION) in the Faculty 0 f Education O Graeme Waymark, 1988 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY NOVEMBER, I988 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Graeme Stuart Waymark Degree: Master of Arts (Education) Title of Thesis: The Political Influence of the Individual in Educational Policy Making: The Case of the Independent School Act. Examining Committee: Chair: Robert Walker Norman Robinson Senior Supervisor Patrick J. Smith - Associate Professor Dr. I.E. Housego Professor University British Columbia Vancouver, B.C. External Examiner Date Approved 25 doll. /9# PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay The Political Influence of the Individual in Educational Pol icy Making: The Case of the Independent School Act. -

Weller Cartographic Services Ltd

WELLER CARTOGRAPHIC SERVICES LTD. Is pleased to continue its efforts to provide map information on the internet for free but we are asking you for your support if you have the financial means to do so? If enough users can help us, we can update our existing material and create new maps. We have joined PayPal to provide the means for you to make a donation for these maps. We are asking for $5.00 per map used but would be happy with any support. Weller Cartographic is adding this page to all our map products. If you want this file without this request please return to our catalogue and use the html page to purchase the file for the amount requested. click here to return to the html page If you want a file that is print enabled return to the html page and purchase the file for the amount requested. click here to return to the html page We can sell you Adobe Illustrator files as well, on a map by map basis please contact us for details. click here to reach [email protected] If enough interest is generated by this request perhaps, I can get these maps back into print as many users have asked. Thank you for your support, Angus A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z CENTENNIAL VANCOUVER MAP NOTES As Vancouver entered its second century in the 1980s the city 1 1 • Expo 86 (O8, Q7) was the largest special category World underwent considerable change in its downtown core (P6) and Exposition ever staged in North America. -

License Limitation in the British Columbia Salmon Fishery

Environnement Canada Service des peches et des sciences de la mer LICENSE LIMITATION IN THE BRITISH COLUMBIA SALMON FISHERY Economics and Special Industry Services Directorate Pacific Region G. ALEX FRASER Technical Report Series No. PAC/T-77-13 c 1-- LICENSE LIMITATION IN THE BRITISH COLUMBIA SALMON FISHERY G. ALEX FRASER Technical Report Series No. PAC/T-77-13 Economics and Special Industry Services Directorate Pacific Region i - ACKN™11E!X;EMENI'S Although full responsibility for the interpretation contained in this study is accepted by the author, the contribution of Blake Campbell, fonner manager of the Pacific Fegion Econanics Branch, must be emphasised. In 1973, Mr. Ca:rrpbell embarked on a detailed account of the limited licensing prograrme in the British Colunbia Salrron Fis!Ecy. This study, based on an in depth personal k:nONledge gained over years of involverrent with the prograrme's develop:rait and administration, provided the frarrework for this present publica tion. Without Mr. campbell' s preliminary work, this present publication would have suffered greatly. The contribution of others must also be thankfully ack:ncwledged. Several people read and made ca:ments on earlier drafts. The final work includes sugges tions from lbb M:>rley, Will McKay and Jay Barclay of the Econanics unit and Rick Lyrner of the University of British Colunbia. A special note of thanks should go to Dr. C.H.B. Newton, the current director of Econanics and Special Industry Services (Pacific Region), for both his encouragement and his k:nONledgeable ideas and carrrents. Last, but by no means least, thanks should go to Shehenaz Bhatia for her typing of the preliminary and final drafts. -

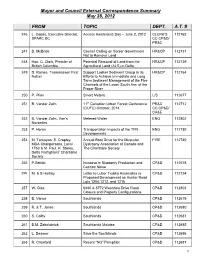

Mayor and Council Correspondence Summary

Mayor and Council External Correspondence Summary May 28, 2012 FROM TOPIC DEPT. A.T. # 246 L. Copas, Executive Director, Access Awareness Day – June 2, 2012 CLERK’S 112762 SPARC BC CC:CP&D/ PR&C 247 D. McBride Council Calling on Senior Government HR&CP 112731 Not to Remove Land 248 Hon. C. Clark, Premier of Potential Removal of Land from the HR&CP 112739 British Columbia Agricultural Land (ALR) in Delta 249 D. Raines, Tsawwassen First Support Ladner Sediment Group in its HR&CP 112764 Nation Efforts to Achieve Immediate and Long Term Sediment Management of the Five Channels of the Lower South Arm of the Fraser River 250 P. Pilon Smart Meters L/S 112677 251 B. Vander Zalm 11th Canadian Urban Forest Conference PR&C 112712 (CUFC) October, 2014 CC:CP&D/ CA&E 252 B. Vander Zalm, Van’s Metered Water ENG 112802 Nurseries 253 P. Horan Transportation Impacts of the TFN ENG 112730 Developments 254 M. Tomayao, S. Cropley, Annual Boot Drive for the Muscular FIRE 112740 MDA Chairpersons, Local Dystrophy Association of Canada and 1763 & M. Paul, K. Storey, The Charitable Society Delta Firefighters’ Charitable Society 255 P.Sziklai Increase in Blueberry Production and CP&D 112678 Cannon Noise 256 M. & S.Hartley Letter to Lubor Trubka Associates re CP&D 112724 Proposed Development on Hunter Road Lots 1204,1212, and 1216 257 W. Gies 6880 & 6772 Westview Drive Road CP&D 112803 Closure and Property Configurations 258 B. Vance Southlands CP&D 112679 259 R. & T. Jones Southlands CP&D 112680 260 S. -

2019-20 Men's Basketball Media Guide

UBC THUNDERBIRDS 2019-20 MEN’S BASKETBALL MEDIA GUIDE GOTHUNDERBIRDS.CA/MBBALL Athletics & Recreation VISION A healthy, active, and connected community where each person is at their personal best and proud of their UBC experience. MISSION To engage our community in outstanding sport and recreation experiences, to enable UBC athletes to excel at the highest levels, and to inspire school spirit and personal well-being through physical activity, involvement, and fun. GOALS To deliver on the vision, we make decisions and prioritize work that will 1. Increase participation 2. Deliver excellence on the national and world stage 3. Build school spirit 4. Nurture a strong sense of community 5. Cultivate an inspired workplace where staff are at their best STRATEGY Our strategy is to invest in partnerships, to leverage resources, and to align with other UBC units and organisations. WHAT WE DO We focus our efforts and resources on: PROGRAMS We deliver engaging, dynamic programs for the whole of our community that increase involvement, in sport and recreation and deliver performance success. LEARNING We provide unique and exciting student learning opportunities that foster personal growth, skill building and leadership development. EVENTS We create high-quality, community-building events where people can connect, have fun and get involved with UBC, recreation and varsity sport. PARTNERSHIPS We invest in cross-campus and community partnerships that drive research and improvement in the areas of high performance sport, fitness and well-being. EXCEL. ENGAGE. INSPIRE. #GoBirdsGo @ubctbirds @ubctbirds /gothunderbirds /ubcathletics STAY UP-TO-DATE WITH YOUR UBC THUNDERBIRDS! FOLLOW US ON TWITTER, INSTAGRAM, FACEBOOK & YOUTUBE • 115 ALL-TIME U SPORTS • 200+ ALL-TIME CANADA WEST • 15 ALL-TIME NAIA CHAMPIONSHIPS (MOST OF ANY CHAMPIONSHIPS CHAMPIONSHIPS UNIVERSITY) • 6 CANADA WEST CHAMPIONSHIPS • 3 NAIA CHAMPIONSHIPS IN • 3 U SPORTS CHAMPIONSHIPS IN IN 2019-20 SEASON 2018-19 SEASON 2019-20 SEASON •4 22 ALL-TIME UBC OLYMPIANS • 58 OLYMPIC MEDALS 2019 - 20 UBC THUNDERBIRDS ROSTER NO. -

OOTD March 2018

Orders of the Day The Publication of the Association of Former MLAs of British Columbia Volume 24, Number 2 March 2018 Memories of the great Dave Barrett Happy Holidays by Glen Clark Dave Barrett arrived at the podium impeccably but ever so slightly. The crowd responded warmly and dressed, wearing a blue pin stripe suit, white shirt and red politely. tie. He started speaking slowly, somberly, to the assembled crowd of supporters – me included. But Dave’s genuine indignation was soon fuelling his passion. Like all great orators, Dave fed off the energy in As the BC opposition leader described the latest social the room and soon was in full eloquent flight. Off came injustice perpetrated by the Social Credit government of the jacket. The white shirt sleeves rolled up without the day, his voice got louder and his cadence quickened, missing a beat in his speech. continued on Page 4 Under the Distinguished Patronage of Her Honour The Honourable Judith Guichon, OBC Thank You and Miscellany Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia In memoriam. We recently learned of the passing of Louise Pelton on Orders of the Day is published regularly throughout the year, and is circulated to February 2 of this year. She was the widow of Austin Pelton, Social Credit Association members, all MLAs now serving in MLA for Dewdney 1983-91. Louise continued to subscribe to OOTD after Legislature, other interested individuals and organizations. Austin’s passing in 2003, and we offer our condolences to her family and Material for the newsletter is always welcome friends. and should be sent in written form to: P.O.