License Limitation in the British Columbia Salmon Fishery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premier Bennett to Start Off Running

_ _ o . % IR071IICIAL LIH.~AR¥ P.~RLIAUE.~Ir BLDg. Premier Bennett to start off running Details of the planned, Nothing official is planned with council, the Regional Following the dinner cabinet' before their Alex Fraser, Highways visit of the British Columbia"~ for the party on the 22rid. District, the press and other during which the Premier departure for Terrace. No Minister will be in the Cabinet are more or less However the Premier's day official engagements. The will make a speech, the brlef will be accepted uniess Hazeltons while Don complete. The Premier will will start very early on the only chance the general cabinet will meet in a this procedure has taken Phillips will visit the Prince arrive in Terrace- on the 23rd as he will be jogging public will have to speak regular cabinet session in place. The briefs will be Rupert area, Other 22nd in one of the govern- around the track at Skeena with the Premier wfll be at a the Senior Citizens Room of accepted one by one with a ministers will also. be ment jets. He Will be ac- Junior Secondary School •dinner sponsored by the the Arena Complex. This spokesman allowed to speak making contact in various companied by Provincial getting underway at 6:30 Terrace Centennial Lions meeting is closed to all. It in support of the brief before areas. will get underway at 2 p.m. •the cabinet. For last minute details of Secretary Grace McCarthy, a.m. The Premier invites all between noon and 2 p.m. .... Following the brief the cabinet visit information his Executive Assistant school children and citizens This will be held at the From 3 p.m. -

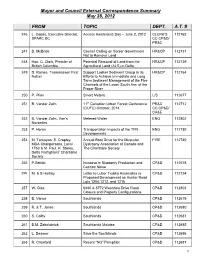

Mayor and Council Correspondence Summary

Mayor and Council External Correspondence Summary May 28, 2012 FROM TOPIC DEPT. A.T. # 246 L. Copas, Executive Director, Access Awareness Day – June 2, 2012 CLERK’S 112762 SPARC BC CC:CP&D/ PR&C 247 D. McBride Council Calling on Senior Government HR&CP 112731 Not to Remove Land 248 Hon. C. Clark, Premier of Potential Removal of Land from the HR&CP 112739 British Columbia Agricultural Land (ALR) in Delta 249 D. Raines, Tsawwassen First Support Ladner Sediment Group in its HR&CP 112764 Nation Efforts to Achieve Immediate and Long Term Sediment Management of the Five Channels of the Lower South Arm of the Fraser River 250 P. Pilon Smart Meters L/S 112677 251 B. Vander Zalm 11th Canadian Urban Forest Conference PR&C 112712 (CUFC) October, 2014 CC:CP&D/ CA&E 252 B. Vander Zalm, Van’s Metered Water ENG 112802 Nurseries 253 P. Horan Transportation Impacts of the TFN ENG 112730 Developments 254 M. Tomayao, S. Cropley, Annual Boot Drive for the Muscular FIRE 112740 MDA Chairpersons, Local Dystrophy Association of Canada and 1763 & M. Paul, K. Storey, The Charitable Society Delta Firefighters’ Charitable Society 255 P.Sziklai Increase in Blueberry Production and CP&D 112678 Cannon Noise 256 M. & S.Hartley Letter to Lubor Trubka Associates re CP&D 112724 Proposed Development on Hunter Road Lots 1204,1212, and 1216 257 W. Gies 6880 & 6772 Westview Drive Road CP&D 112803 Closure and Property Configurations 258 B. Vance Southlands CP&D 112679 259 R. & T. Jones Southlands CP&D 112680 260 S. -

Assessment of Post-Disturbance Regeneration in the Ubc Alex Fraser Research Forest’S (Afrf’S) Knife Creek Block

NATURAL REGENERATION DYNAMICS OF INTERIOR DOUGLAS-FIR: ASSESSMENT OF POST-DISTURBANCE REGENERATION IN THE UBC ALEX FRASER RESEARCH FOREST’S (AFRF’S) KNIFE CREEK BLOCK by Emmanuel Adoasi-Ahyiah B.Sc., Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, 2017 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Forestry) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) September 2020 © Emmanuel Adoasi-Ahyiah, 2020 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the thesis entitled: Natural Regeneration Dynamics of Interior Douglas-fir: Assessment of Post-disturbance Regeneration in the UBC Alex Fraser Research Forest’s (AFRF’S) Knife Creek Block submitted by Emmanuel Adoasi-Ahyiah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Forestry Examining Committee: Dr. Verena C. Griess, Associate Professor, Department of Forest Resources Management, UBC Supervisor Dr. Adam Polinko, Post-doctoral Fellow, Department of Forest Resources Management, UBC Supervisory Committee Member Dr. Allan Carroll, Professor, Department of Forest and Conservation Sciences, UBC Supervisory Committee Member Dr. Lori Daniels, Professor, Department of Forest and Conservation Sciences, UBC Additional Examiner i Abstract Licensees are required to regenerate interior Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menzisii var glauca) forest gaps greater than 0.1ha to meet and maintain species distribution across age classes for stands, biodiversity (such as mule deer winter range (MDWR)), and recreational objectives. However, little is known about the dynamics of natural regeneration in these forests. To understand future stand structure and composition, I investigated the regeneration dynamics and growth of interior Douglas-fir post-disturbance, and the influence of growing space availability on the dynamics of interior Douglas-fir regeneration and growth. -

GULF ISLANDS PROPERTIES Pagec2 GULF ISLANDS DRIFTWOOD Wednesday

SECTION C WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 29, 1990 Island Living ISLAND SAVINGS Real Estate CREDIT UNION Crofton Springs in Ganges New Corbett complex tThoe laceask of rentael unit srenta in Ganges "lI hav demane yet to get a bad commendt from should be eased somewhat when Crofton anybody on the project as a whole," he Springs is completed. said. Crofton Springs will be a planned 23- The units will be built in three phases unit complex situated at the end of Cor• with an initial set of five units being bett Road (off Crofton Road in Ganges). started soon. The second phase will con• Each unit will be 116- square-metres tain eight units with the final 10 being (1,260 square feet) on two floors with a built later. rental price of $725 per month. The project will be situated on the The proposal is being put forward by Corbett Road property with a maximum Godfrey Miller who came to Salt spring 15 per cent site coverage. In this way, four years ago. At that time, he and his Miller can retain a spring-fed pond and family experienced difficulty in finding a avoid cutting down several large, old rental unit. trees. "There was just nothing for long term Three trees in particular will be incor• rental," he recalled. porate -A into the complex. A willow tree, Finally, the family found a home and at least 65 years old, towers close to 37 as they settled in Miller began building metres (120 feet) over the property while rental units around Salt Spring. -

Volume Index

VOLUME INDEX FOR THE DIRECT TRANSFER COAL FACILITY ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT VOLUME 1: MAIN DOCUMENT VOLUME 2: APPENDICES I TO VII Appendix I: Project Application to Port Metro Vancouver (PMV) Appendix II: Binding and Suppression Agents Appendix III: Dust Control and Anti-Idling Appendix IV: Procedures for Small and Large-Scale Coal Spills Appendix V: Standard Operating Procedures for Barge Transport Appendix VI: Environmental Management Plans Appendix VII: Community Engagement VOLUME 3: APPENDICES VIII TO IX Appendix VIII: Draft Air Quality Assessment and Draft Air Quality Management Plan Appendix IX: Health Effects Associated with Exposure to PM Appendix X: Metro Vancouver Wildlife List (HectaresBC 2013) Appendix XI: Plants with Special Status Appendix XII: Wildlife with Special Status Appendix XIII: Expert Letters Appendix XIV: VanHook Statement (Fall 2012) VOLUME 4: ATTACHMENTS Engineering Drawings VOLUME INDEX FOR THE DIRECT TRANSFER COAL FACILITY ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT VOLUME 1: MAIN DOCUMENT VOLUME 2: APPENDICES I TO VII Appendix I: Project Application to Port Metro Vancouver (PMV) Appendix II: Binding and Suppression Agents Appendix III: Dust Control and Anti-Idling Appendix IV: Procedures for Small and Large-Scale Coal Spills Appendix V: Standard Operating Procedures for Barge Transport Appendix VI: Environmental Management Plans Appendix VII: Community Engagement VOLUME 3: APPENDICES VIII TO IX Appendix VIII: Draft Air Quality Assessment and Draft Air Quality Management Plan Appendix IX: Health Effects Associated -

Site Units of the University of British Columbia Alex Fraser Research Forest

Site Units of the University of British Columbia Alex Fraser Research Forest K. Klinka, P. Varga, C. Trethewey, C. Koot, M. Rau, J. Macku and T. Kusbach © UBC Alex Fraser Research Forest May 2004 i Site Units of the University of British Columbia Alex Fraser Research Forest K. Klinka 1, P. Varga 1, C. Trethewey 2, C. Koot 2, and M. Rau 2 In collaboration with J. Macku 3 and T. Kusbach 3 1 Forest Sciences Department University of British Columbia 3041-2424 Main Mall Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Cananda 2 University of British Columbia Alex Fraser Research Forest 72 South 7th Avenue Williams Lake, BC V2G 4N5, Canada 3 Ustav pro Hospodarskou Upravu Lesu (Forest Management Institute) Brandys nad Labem, Czech Republic May 2004 © UBC Alex Fraser Research Forest UBC Alex Fraser Research Forest ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Assistance of C. Chourmouzis and X. Wang, UBC Forest Sciences Department, in reconnaissance, C. Chourmouzis in preparing the paper and pdf version of this report, B.A. Blackwell and Associates, Ltd., North Vancouver, BC, in ecosystem sampling, Paragon Resource Mapping Inc., Williams Lake, BC, in digital line capture, Pacific Soil Analysis, Inc., Richmond, BC, in chemical analysis, and K. Day, UBC Alex Fraser Research Forest, Williams Lake, BC, for financial and logistic support is gratefully acknowledged. BC Ministry of Forests, and Forestry Innovation Investment (for the second year of the two year project) provided funding for this project. PHOTO CREDITS The cover photograph is of Gavin Lake, taken from the field camp in the Gavin Lake Block of the UBC Alex Fraser Research Forest. -

VANCOUVER an Entry Fee of $5 a Curler

/ Legislative Library, OT- Parliament Buildings, Victoria, B.C. *a rn~. ~... Vol. 2, Issue No. 41 TERRACE, B.C., WEDNESDAY, October 8, 1986 50 (..b N i,~ II I Wildlife Shames corp.oration danger gets sk equ pment / TERRACE -- The president of the Shames throughout the coming cited Kitimat-Stikine Regional Mountain Ski Corpora- winter on the ski trails, TERRACE- Lamont District board of direc- tion. "We're excited -- and he said blasting to Bassett, a member of the tors voted unanimously this is one more hurdle build the access road to Spatzizi Association, Oct. 4 to have a contract we've gone over." the base area will also recently warned board drawn up for Sale of all Lissimore went on to continue. directors of the Kitimat- assets from the Kit- confirm that the Shames In correspondence to Stikine Regional District sumkalum Ski Hill to the corp. will open the Kit- the regional district, Ed that use of a coal-fired Shames Mountain Ski sumkalum operation for , Opal from the Ministry power generator at the Corporation. Final business during the of Forests and Lands in- Mt. Klappan coal project ratification of the con- 1986-87 season, pro- dicated that his ministry will endanger wildlife on tract will be voted on by - riding local skiing for is presently considering the Spatzizi Plateau. the board at a special Terrace-Kitimat area the formal development Bassett said the Spat- meeting Oct. 9. residents. proposal from the zizi Association has been The successful bid In the mean time, Shames Corp. The pro- closely studying the came in at $306,000 for work will continue on posal calls for develop- habits of large mammals everything on the moun- the Shames Mountain ment on 1955 hectares of such as caribou, moose, tain that isn't nailed development in an effort land in four phases with mountain goats and down, including T-bars, to meet the target com- an eventual capacity of stone sheep since 1980 chairlifts, grooming and pletion date of fall 1987. -

Provincial B.C P R O B L E M S P I L I N G U P BCGEU

2 — The Prince George Citizen — Monday, July 18,1988 Provincial B.C P r o b l e m s p i l i n g u p BCGEU d e m a n d s f o r B . C / s p r e m i e r ' c o s t l y ' by STEVE MERTL Canadian Press VICTORIA (CP) - The B.C. VANCOUVER — It was a bad week in a string of Government Employees’ Union ha£ bad weeks for Bill Vander Zalm. tabled non-wage demands which The premier of British Columbia was facing a would cost taxpayers almost $100 calls for a leadership review from within his Social million, the government’s chief ne Credit caucus, stirrings in party grassroots, more gotiator said Sunday. flak aimed at his principal adviser and, out of left Bob Plecas said the union has field, suggestions that he was consulting a numero- not yet made specific wage de logist on government policy. mands in its contract talks, except But Vander Zalm let his anger show only briefly, to indicate that it will seek “cat when word got out that his office had a $1,500 con chup” increases. tract with a numerologist. The agreement with Jud Union president John Shields Cyllorn, who said he was hired to advise the premier said earlier that five years of fiscal on immigration and economic policy, was promptly withdrawn. restraint have put his 29,000 mem|T^) Direction and speed of system motion A A A. ColdA front “I am a practical kind of guy and I don’t believe bers an average of 17 per cent be in that kind of garbage,” said Vander Zalm, who hind their counterparts in the pri 0 Rain or snow showers Warm front then attacked the Vancouver Province for running vate sector and other levels of gov the story. -

POLICE SEEK MASS MURDERER 2 Bodies Found; 2 More Sought

• . • ..,,.. • ... ,., ,. .'.'.~'~'~'~'~'~'~'.';'.~'~'i'~';,~.;.~./.~:.~.~.~,',-,',-~,',',',',',',',-,',','e_~,_-,.,:,~,,,,.,,s~ ~.,~'~.,C~'*F.~÷:;~.~..'. ' " "'" " "','~',,"" ~:::~'~'.~::.~':~'/~'~k:'~:~:~.~:~..~.~.~..~" "F.,"* , ,-.':,'~s,'~,~ *',~'f'/.,:~"~,;,:,~,'-~.~~ ~'~::.¢~::~/;/.~:~¢ t~ ,.'~¢,:,:,s,~.,. ~'~';., ~~~fo'.,:~'~::~2:~-'~::~-~.~.~.~.~.~.~.~" ~ -~ ~ ' " - .... ~ ~ - ~t~ .'.-~ '-":*'~"""*";"SP/~''':'""":~'"'"""''=.~...;.;.~.~.~..~...;~..; ..,.............. -" ~ . : :- ~,',,~~,:.i.,-~,.:.i, :.~:. :".: .', : " ~-~::,: i~:"/:-'~":;:,'~","-~.~',":~ '~': .... ". ~.":.'- .':~!: -,: ~- - '" "~: ' ~ ':: '\ • ..... ' .... ' BOB HALLSOR .GETS THE NOD . R0.u..,tine ::admin istrat.i ve ' Sele ction runs into sn.ags ' By ALLAN KRASNICK Hallaor's appointment but He told the Herald that he was sworn in by Justice of Northwest Real Estate majorHallsor alte'rahonsanticipates " noin Managing Editor he wanted .to learn more wanted committee, of the the Peace Fred Smith. Board. -. aboutthe decision.... whole discussion "so I could The new clerk- - Continuity, both with civic. Terrace's administration The usually • routine "I was in a difficult be tom why Hallsor was administrator has heen with adminintrationand the city thoughthere may be minor sweuring-in of a new clerk- position because, as an chos=-n." . the district since January itself, -is an advantage Changes in structure to edministratorranintoafew applicadt,.~there was a "There's no way I could but hisroofs in ~Terrace Hallsor undoubtedly streamline systems. The snags, Tuesday -

SQUAMISH. HOTEL One Gallon of 3241 2Nd Avenue, Squamish General Paint ,8924422 -Vy , a Birthday'

HQWE SOUND Second Class Mail Registration Number i i4i Return Postage Guaranteed It was an impressive either as new members. veteran reremsny Gxe:nme::! Hsuse ~ members c?f the house, or in P~blishedby !?oorlspi!h Pnb!ishing Cc. Ltd.. every fhcrsd2.y I! Sqnamish, E.C. i:: on that Monday morning of several cases as members of a CLAUDE S. 0. HOODSPITH - Plablleher Cliristmas week. In the drawing new.party. One sad note was the room where all the furniture empty green chair beside Mrs. had been moved out except for Walter Owen, reserved for Mrs. one small tablc and three green Bennett. who was unable to be velvet chairs, a Christmas swag present at the ceremcny because P.0. BOX 107, Squamirh, B.C. decorated the mantel of the weather delayed their plane. Subscription Rates (Delivered by Mail): $5.00 per Year fireplace. In the corner of the It would also have been fitling 67.00 per Year Outside Canada large room beyond where the for former premier W.A.C. 5en- annual Christmas party had nett and Mrs. Bennett to have !?eel? he!d thc nigh! hpfbre, you Seen their son sworn in as could see' the huge Christmas premier but perhaps they will tree, stretching to the ceiling. attend the first opening of the covered with glowing lights. legislature later this year. VI)^. 20 - NO. I There were brilliant lights **t ' throughout the room. massed on Getting on and off the island - the small table where can be a problem though. Get- Lieutenant-Governor Walter ting there for the ceremony Owen hcard the premier-elect wasn't too much irouble. -

Ubcforestryar2010.Pdf

2010 FORESTRY ADVISORY COUNCIL The Forestry Advisory Council provides advice to the Faculty on curriculum matters and research priorities. Mr George Weyerhaeuser (Chair) Mr Rick Jeffery Retired Weyerhaeuser Senior VP President and CEO Coast Forest Products Association Mr Nick Arkle Chief Forester Mr Doug Konkin Gorman Brothers Lumber Ltd Deputy Minister Ministry of Forests, Lands and Mr Keith Atkinson Natural Resource Operations Executive Director First Nations Forestry Council Ms Brenda Kuecks President Mr Ken Baker Ecotrust Canada CEO Forest Innovation Investment Ltd Mr Pierre Lapointe President and CEO Dr Clark Binkley FPInnovations Managing Director International Forestry Investment Advisors Mr Dave Lewis President Dr Bill Bourgeois Truck Loggers Association President New Direction Resource Management Ltd Mr Garry Merkel Principal Mr Reid Carter Forest Innovations Managing Partner Brookfield Asset Management Inc Mr Paul McElligott President and CEO Mr Wayne Clogg TimberWest Forest Corp Senior Vice President of Woodlands West Fraser Timber Co Ltd Mr Bruce McIntyre Partner Mr David Gandossi PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP Executive Vice President, CFO & Secretary Mercer International Mr Eduardo Rojas-Briales Assistant Director General Ms Anne Giardini FAO Forestry Department President Weyerhaeuser Company Ltd Mr Tom Rosser Assistant Deputy Minister Ms Sharon Glover Canadian Forest Service, Natural Resources Canada CEO Association of BC Forest Professionals Mr Gerry Salembier Assistant Deputy Minister, Western Economic Ms Dana Hayden Diversification -

Forestry in the Cariboo Since MWP#2 Was Written in 1996

UBC Alex Fraser Research Forest Management And Working Plan #3 Effective January 1, 2007 to December 31, 2012 Special Use Permit 15382 FoUniversity of Britishrestr Columbia Welcome to Our Classroom 72 South Seventh Avenue, Williams Lake, BC V2G 4N5 Phone (250) 392-2207 Fax (250) 398-5708 Email [email protected] January 5, 2007 Al Balogh, RPF District Manager Central Cariboo Forest District 640 Borland St. Williams Lake, BC V2G 4T1 Dear Sir: Re: Letter of Transmittal, Management and Working Plan #3, SUP 15382 Pursuant to our tenure agreement, please find enclosed Management and Working Plan #3. This document is intended to guide the management of our Research Forest by resolving our management objectives with strategic direction from the Forest and Range Practices Act and the Cariboo Chilcotin Land Use Plan. There have been substantial changes to the practice of forestry in the Cariboo since MWP#2 was written in 1996. Working within that Management Plan has helped us to react to change in a constructive manner, and I fully expect that this new plan will continue to support our activities as our world continues to change around us. I would like to direct your attention to several unique aspects of this plan. x I have taken the step of summarizing the history of the area we manage, in the belief that our future is strongly influenced by our past. x I am proposing that we convert our forest management to area regulation, and as such have stated our Allowable Annual Cut in hectares instead of cubic metres. x We will implement an ongoing process of consultation, rather than simply referring this plan for comment.