Birdobserver24.4 Page204-210 the Identification Guide Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engelsk Register

Danske navne på alverdens FUGLE ENGELSK REGISTER 1 Bearbejdning af paginering og sortering af registret er foretaget ved hjælp af Microsoft Excel, hvor det har været nødvendigt at indlede sidehenvisningerne med et bogstav og eventuelt 0 for siderne 1 til 99. Tallet efter bindestregen giver artens rækkefølge på siden. -

1994 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals

The lUCN Species Survival Commission 1994 lUCN Red List of Threatened Animals Compiled by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre PADU - MGs COPY DO NOT REMOVE lUCN The World Conservation Union lo-^2^ 1994 lUCN Red List of Threatened Animals lUCN WORLD CONSERVATION Tile World Conservation Union species susvival commission monitoring centre WWF i Suftanate of Oman 1NYZ5 TTieWlLDUFE CONSERVATION SOCIET'' PEOPLE'S TRISr BirdLife 9h: KX ENIUNGMEDSPEaES INTERNATIONAL fdreningen Chicago Zoulog k.J SnuicTy lUCN - The World Conservation Union lUCN - The World Conservation Union brings together States, government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organisations in a unique world partnership: some 770 members in all, spread across 123 countries. - As a union, I UCN exists to serve its members to represent their views on the world stage and to provide them with the concepts, strategies and technical support they need to achieve their goals. Through its six Commissions, lUCN draws together over 5000 expert volunteers in project teams and action groups. A central secretariat coordinates the lUCN Programme and leads initiatives on the conservation and sustainable use of the world's biological diversity and the management of habitats and natural resources, as well as providing a range of services. The Union has helped many countries to prepare National Conservation Strategies, and demonstrates the application of its knowledge through the field projects it supervises. Operations are increasingly decentralised and are carried forward by an expanding network of regional and country offices, located principally in developing countries. I UCN - The World Conservation Union seeks above all to work with its members to achieve development that is sustainable and that provides a lasting Improvement in the quality of life for people all over the world. -

Sitta Ledanti) En Période De Reproduction

Retour au menu Premières données sur le comportement alimentaire de la Sittelle kabyle (Sitta ledanti) en période de reproduction Bellatreche M., et Boubaker Z. Institut National Agronomique, El Harrach, 16200 - Alger. Bellatreche M., et Boubaker Z., 199.5 - Premières données sur le comportement alimentaire de la Sittelle kabyle (Sitta ledanti) en période de reproduction. Ann. &-on. I.N.A., Vol.16, N”I et 2, pp. 35 - 48 Résumé : Notre travail a pour objectif principal la connaissance de certains aspects de l’écologie de la Sittelle kabyle Sitta ledanti Vielliard, espèce endémique d’Algérie, propre à la Kabylie des Babors. L’intérêt de l’étude de cette espèce forestière, sur le plan biologique, écologique et éthologique, est d’une grande importance. En effet, cette espèce est un témoin vivant de toute une faune avienne qui a survécu aux vicissitudes climatiques qu’a connue la région méditerranéenne depuis le tertiaire. Parmi les différents aspects de la biologie de Sitta ledanti, son comportement alimentaire en période de reproduction a retenu notre attention depuis 1991. C’est dans les chênaies de la forêt domaniale de Guerrouch, à l’intérieur des limites du Parc National de Taza, que nous avons entrepris nos recherches, grâce à l’expérimentation d’une méthodologie que nous avons adaptée spécialement à cette espèce. Comme premiers résultats, intéressants, il faut souligner la mise en évidence de certains aspects de l’écologie de Sitta ledanti, notamment ses préférences trophiques, ainsi que sa technique d’acquisition de la nourriture durant sa quête alimentaire. La technique la plus utilisée, qui consiste à glaner les proies sur les branches et les troncs, semble même être une caractéristique spéciale à la Sittelle kabyle, puisque cette technique est rarement utilisée par les deux autres espèces de sittelles méditerranéennes, la Sittelle de corse Sitta whiteheadi et la Sittelle de kruper Sitta kruperi. -

CAMARGUE and CORSICA May 2014

CAMARGUE AND CORSICA two beautiful destinations in one exciting trip French folklore and literature are strewn with tales and references to the wil d Corsican Nuthatch white horses, the gypsies and the fighting bulls for which the Camargue is famed. The most discerning birdwatcher will, however, find that the region has even more to offer. There is a very satisfying range of habitats, from reedbeds and marshes to open stony plains. Add to these riparian woodland, limestone hills and imposing mountains and you will appreciate why this is one of our most popular destinations. Breathtaking mountain scenery, scented hillsides, an interesting coastline and unique birdlife combine to make Corsica one of the most attractive Mediterranean islands. The Camargue and Corsica complement each other perfectly. We will spend five nights at Arles, just north of the Camargue, visiting all the sites we have come to love in this part of Provence. On day six we will catch a flight to Ajaccio, spending three nights at Corte in Corsica’s mountainous interior. ITINERARY Spectacled and Fan-tailed Warblers. They are, however, drowned out by three of the loudest songsters, Great Reed CAMARGUE Warbler, Cetti's Warbler and Nightingale. Having arrived at Nice we will make the two and a half hour drive to Arles, our base for the first five nights. Marsh Harriers hunt low over the reedbeds to the concern of We discovered the Hotel des Granges back in 1990. It is in nesting ducks, which include Red-crested Pochard, Garganey the perfect location for visits to the Camargue, Les Alpilles, and Shelduck. -

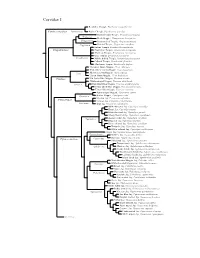

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

Adobe PDF, Job 6

Noms français des oiseaux du Monde par la Commission internationale des noms français des oiseaux (CINFO) composée de Pierre DEVILLERS, Henri OUELLET, Édouard BENITO-ESPINAL, Roseline BEUDELS, Roger CRUON, Normand DAVID, Christian ÉRARD, Michel GOSSELIN, Gilles SEUTIN Éd. MultiMondes Inc., Sainte-Foy, Québec & Éd. Chabaud, Bayonne, France, 1993, 1re éd. ISBN 2-87749035-1 & avec le concours de Stéphane POPINET pour les noms anglais, d'après Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World par C. G. SIBLEY & B. L. MONROE Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1990 ISBN 2-87749035-1 Source : http://perso.club-internet.fr/alfosse/cinfo.htm Nouvelle adresse : http://listoiseauxmonde.multimania. -

Diversity and Dynamics of Potential

Studia Universitatis “Vasile Goldiş”, Seria Ştiinţele Vieţii Vol. 30, issue 3, 2020, pp. 136 - 144 © 2020 Vasile Goldis University Press (www.studiauniversitatis.ro) DIVERSITY AND DYNAMICS OF POTENTIAL PREY OF THE ALGERIAN NUTHATCH SITTA LEDANTI DURING THE BREEDING SEASON Mohammed El Arbi MAYACHE1*, Lakhdar TEMAGOULT1, Mouslim BARA1,2 Riadh MOULAÏ1 1 Laboratoire de Zoologie Appliquée et d’Ecophysiologie Animale, Faculté des Sciences de la Nature et de la Vie, Université de Bejaia, Algérie 2 Laboratoire Biologie Eau et Environnement, Faculté SNVSTU, Université 8 Mai 1945, Guelma, Algérie Abstract: This current study is focused on the trophic menu of the Algerian Nuthatch Sitta ledanti in the Guerrouch forest (Algeria). The sampling was done during the breeding season (from March to June 2018) of this bird. The results exposed the importance of Lepidopteran larvae on the diet of the Nuthatch. This taxa was the most diversified and abundant order with 20 species. The available prey associated with the Algerian Oak is more abundant during the incubation and the feeding young phases. These preys are much less present during the pre-laying and post-flight phases. During egg incubation and feeding, periods when the nuthatches' food and energy requirements are at their peak. The average size of prey available during the nesting period is 14.05±7mm. Potential prey sizes for Nuthatches, on average, are higher, more in advance of the breeding period. Geometridae are dominant during the incubation phase of the brood, represented mainly by the species Operophtera brumata. Caterpillars with a dominant green color are the most available for Nuthatches with a rate of 80 %. -

Annual Report 2020

ASIAN SPECIES ACTION PARTNERSHIP ANNUAL REPORT 2020 WWW.SPECIESONTHEBRINK.ORG @IUCN_ASAP CONTENTS Rote Island Snake-necked Turtle Chelodina mccordi © Wildlife Reserves Singapore 3 IUCN SSC Asian Species Action Partnership 4 Message from the Chair 5 Message from the Director 6 ASAP impact 7 The impact of COVID-19 8-14 Leveraging funds for ASAP species conservation 8-10 ASAP Species Rapid Action Fund 11-12 ASAP Species Conservation Grants 15 Strengthening regional capacity 16 Raising the profile of ASAP species 17 The Partnership 18 Governance 19 Acknowledgements Cover image: Giant Carp Catlocarpio siamensis © David Tan/Wildlife Reserves Singapore ASAP Annual Report 2020 - Page 2 IUCN SSC ASIAN SPECIES ACTION PARTNERSHIP Vision Species extinctions in Southeast Asia have been averted and wild populations are secure and thriving across their natural range 15 43 reptiles amphibians 246 16 ASAP +1 freshwater 46 mammals 55 birds species* fishes up from 226 at the 87 fishes in Southeast Asia end of 2019 +5 declared extinct in 2020 +28 A significant number of species have been added Freshwater fishes now make up to the ASAP species list during 2020. Much of this increase comes from freshwater fishes, a group which is threatened across Southeast Asia from 35% overfishing (both for consumption and the global of all ASAP species aquarium trade), invasive fish species, pollution, dam construction and habitat loss – scores of peatland “So far, freshwater fishes have received a raw deal in species are threatened from conversion to oil palm conservation terms because – as a group, and even plantations. more so as individual species – they simply do not resonate as much with most people as the big furry In the latest update to the IUCN Red List published and feathery species. -

Beyond Sulawesi

BEYOND SULAWESI 7 NOVEMBER – 2 DECEMBER 2011 TOUR REPORT LEADERS: MARK VAN BEIRS and CRAIG ROBSON This was the first ever organized bird tour to these little-known specks of land situated between mainland Sulawesi and the Moluccas, just to the west of Weber’s zoogeographical Line. We visited the little known island groups of Talaud, Banggai, Sula, the Togians and Sangihe and came away with excellent views of the majority of the extant endemics. The logistics went unexpectedly smooth and although we had to work quite hard at times to get to the habitat of some of the specialities, we got rewarded with some exceptional observations of some of the least known and rarest species on the planet. The bird of the trip was the modestly-clad Sangihe Shrike-Thrush, not only because we will long remember the long hike on steep, slippery trails to get to its beautiful, montane forest habitat, but mainly because of the terrific views we had of this extremely rare species. Other mega highlights included the cute Sangihe Scops Owl, the remarkable Togian Boobook, the seriously weird Banggai Crow, the smart Bare-eyed Myna, the terrific Helmeted Myna and the unpretentious Sula Scrubfowl. We recorded 205 species on our travels. Mammals were not very obvious but both the Peleng and Sangihe Tarsiers conquered our hearts with their enormous eyes. Other interesting animals included Peleng Cuscus, Sulawesi Crested Macaque and Short-finned Pilot Whale. The group convened at our hotel outside Manado, the capital of the weird-shaped island of Sulawesi. In the afternoon we explored the beautiful gardens and started the list with beauties like Barred Rail, Black-billed Koel, Black-fronted White-eye and Chestnut and Scaly-breasted Munias. -

Nest Characteristics of the Eastern Rock Nuthatch (Sitta Tephronota) in Southwestern Iran

Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 66(1), pp. 85–98, 2020 DOI: 10.17109/AZH.66.1.85.2020 NEST CHARACTERISTICS OF THE EASTERN ROCK NUTHATCH (SITTA TEPHRONOTA) IN SOUTHWESTERN IRAN Arya Shafaeipour1*, Behzad Fathinia1 and Jerzy Michalczuk2 1Department of Biology, University of Yasouj, Yasouj, Iran E-mails: [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4267-536X [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5752-9288 2Department of Nature Protection and Landscape Ecology, University of Rzeszów Zelwerowicza 4, 35-601 Rzeszów, Poland E-mail: [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9311-7731 In the springs of 2015–2017, the population size and nest characteristics of the Eastern Rock Nuthatch (Sitta tephronota) were investigated. The study was conducted in a 400 hectare area of the mountainous region of southwestern Iran. In 2016, the population of the Eastern Rock Nuthatch was estimated at 33 pairs and its density was 8.25 breeding pairs per 100 ha of the study area. During the study, 45 nuthatch nests were investigated, of which 15 (33%) were found in cliffs and 28 (62%) were located in tree holes; 2% were built in house and bridge walls. The height of the nest was 214.3±112.3 cm above ground level. The mean of the horizontal and vertical depths of the nest chambers in trees was 17.8±3.7 and 12.6±3.2 cm respectively, and statistically differed from those in rocky nests (respectively 23.9±5.5 and 10.8±4.6 cm). However, chamber volumes did not statistically differ between these two nest type categories. -

Page De Garde

Project for the Preparation of a Strategic Action Plan for the Conservation of Biological Diversity in the Mediterranean Region (SAP BIO) IMPACT OF TOURISM ON MEDITERRANEAN MARINE AND COASTAL BIODIVERSITY Project for the Preparation of a Strategic Action Plan for the Conservation of Biological Diversity in the Mediterranean Region (SAP BIO) IMPACT OF TOURISM ON MEDITERRANEAN MARINE AND COASTAL BIODIVERSITY RAC/SPA - Regional Activity Centre for Specially Protected Areas 2003 Note: The designation employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of RAC/SPA and UNEP concerning the legal status of any State, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of their frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in the document are those of the author and not necessarily represented the views of RAC/SPA and UNEP. This document was prepared within the framework of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) concluded between the Regional Activity Center for Specially Protected Areas (RAC/SPA), and BRLingénierie. prepared by: Jean-Denis KRAKIMEL Geograph BRLingenierie BP 4001 - 1105 avenue Pierre Mendes-France 30001 Nimes - France Tel 33 (0)4 66 87 50 29 ; Fax 33 (0)4 66 87 51 03 E-mail: [email protected] ; Web: http://www.brl.fr/brli/ Mars 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Our thanks go first to the Tunis RAC/SPA, which provided the necessary works for this books. We should also like to thank internet and all the local, national and international organisations, ministries, backers, enforcement agencies, NGOs, committees, tour operators, universities, research institutes and also all those people who are just nature-and travel- lovers and so many others, who share the whole world their data, their projects, their experience and their thoughts, and without whom such a labour of compilation, far from being exhaustive, would not have been possible CONTENTS 1INTRODUCTION 1 1.1Background to the study 1 1.2 Documentation 3 2.SITUATION BY COUNTRY 6 2.1.Albania 6 2.2.Algeria 9 2.3. -

Obituary – Jacques M

ISSN (impresso) 0103-5657 ISSN (on-line) 2178-7875 Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia Volume 19 Número 3 www.ararajuba.org.br/sbo/ararajuba/revbrasorn Setembro 2011 Publicada pela Sociedade Brasileira de Ornitologia São Paulo - SP Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 19(3), 455-459 NECROLÓGIO Setembro de 2011 Obituary – Jacques M. E. Vielliard (1944-2010) life and legacy Carlos B. de Araújo1 and Maria Luisa Silva2 1. Ecology graduate program, Biology Institute, UNICAMP. Caixa Postal 6.109, CEP 13083‑970, Campinas, SP, Brasil. E‑mail: [email protected] 2. Bioacoustics and Ornithology Lab, UFPA. Rua Augusto Corrêa, 1, Caixa Postal 8.618, Guamá, CEP 66075‑970, Belém, PA, Brasil. The Brazilian Ornithological community trem‑ Oriental and Ocidental African biogeographical areas. bled on August 2010 upon the sudden and unexpected This was a productive time for Jacques, as the expedi‑ death of the father of Brazilian Bioacoustics, Jacques tions lead to the first sound guide of this African region, Marie Edme Vielliard. He was still very caught up in his and also the discovery of the last bird described for the work, and had fruitful years ahead of him with impor‑ Palearctic region, the Algerian Nuthatch Sitta ledanti Vi‑ tant publications on many fields involving ornithology elliard 1976. and bioacoustics. For instance, his bioacoustical method A visit of the president of the Academia Brasileira de on quantitative ecology had successfully determined the Ciências (ABC), Aristides Pacheco Leão, would change diversity of a few localities of complex tropical habitats, Vielliard’s life forever. Dr. Leão (a prominent Brazilian and the results were promising.