Cultural Resources Report Cover Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forestry Books, 1820-1945

WASHINGTON STATE FORESTRY BIBLIOGRAPHY: BOOKS, 1820‐1945 (334 titles) WASHINGTON STATE FORESTRY BIBLIOGRAPHY BOOKS (published between 1820‐1945) 334 titles Overview This bibliography was created by the University of Washington Libraries as part of the Preserving the History of U.S. Agriculture and Rural Life Grant Project funded and supported by the National Endowment of the Humanities (NEH), Cornell University, the United States Agricultural Information Network (USAIN), and other land‐grant universities. Please note that this bibliography only covers titles published between 1820 and 1945. It excludes federal publications; articles or individual numbers from serials; manuscripts and archival materials; and maps. More information about the creation and organization of this bibliography, the other available bibliographies on Washington State agriculture, forestry, and fisheries, and the Preserving the History of U.S. Agriculture and Rural Life Grant Project for Washington State can be found at: http://www.lib.washington.edu/preservation/projects/WashAg/index.html Citation University of Washington Libraries (2005). Washington State Agricultural Bibliography. Retrieved from University of Washington Libraries Preservation Web site, http://www.lib.washington.edu/preservation/projects/WashAg/index.html © University of Washington Libraries, 2005, p. 1 WASHINGTON STATE FORESTRY BIBLIOGRAPHY: BOOKS, 1820‐1945 (334 titles) 1. After the War...Wood! s.l.: [1942]. (16 p.). 2. Cash crops from Washington woodlands. S.l.: s.n., 1940s. (30 p., ill. ; 22 cm.). 3. High‐ball. Portland, Ore.: 1900‐1988? (32 p. illus.). Note: "Logging camp humor." Other Title: Four L Lumber news. 4. I.W.W. case at Centralia; Montesano labor jury dares to tell the truth. Tacoma: 1920. -

Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. 19-247 In the Supreme Court of the United States __________________ CITY OF BOISE, IDAHO, Petitioner, v. ROBERT MARTIN, ET AL., Respondents. __________________ On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit __________________ BRIEF OF THE CITY OF ABERDEEN, WASHINGTON AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF THE CITY OF BOISE __________________ JOHN EDWARD JUSTICE MARY PATRICE KENT JEFFREY SCOTT MYERS Corporation Counsel Law, Lyman, Daniel, Counsel of Record Kamerrer & Bogdanovich, P.S. Office of Corporation Counsel, Post Office Box 11880 City of Aberdeen Olympia, WA 98508-1880 200 East Market Street (360) 754-3480 Aberdeen, WA 98520 (360) 357-3511 (fax) (360) 537-3233 [email protected] (360) 532-9137 (fax) [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae City of Aberdeen, Washington in Support of Petition of City of Boise Becker Gallagher · Cincinnati, OH · Washington, D.C. · 800.890.5001 i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES . iii INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE . 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT . 2 ARGUMENT . 3 I. Context/Background . 3 II. Aberdeen Experience: River Street Property ..................................... 5 A. Background ........................ 5 B. Monroe, et al. v. City of Aberdeen, et al. 8 C. Aitken, et al. v. City of Aberdeen . 8 III. Martin does not clearly define “available overnight shelter” . 12 IV. Martin has impermissibly expanded prohibitions against criminalization to generally applicable protections of public health and welfare. 13 V. Martin has created unintended consequences including appropriating of public property for personal use; and shifting responsibility for local management of homelessness to the federal judiciary. 15 A. -

Cultural Context

Cultural Resources Assessment for the Grays Harbor Rail Terminal, LLC Proposed Liquid Bulk Facility, Hoquiam, Grays Harbor County, Washington Contains Confidential Information—Not for Public Distribution Prepared by: Jennifer Chambers, M.S. With contributions by: Melanie Diedrich, M.A., RPA Revised by: Katherine M. Kelly, MES, RPA Tierra Archaeological Report No. 2013-080 March 11, 2014 Cultural Resources Assessment for the Grays Harbor Rail Terminal, LLC Proposed Liquid Bulk Facility, Hoquiam, Grays Harbor County, Washington Contains Confidential Information—Not for Public Distribution Prepared by: Jennifer Chambers, M.S. With contributions by: Melanie Diedrich, M.A., RPA Revised by: Katherine M. Kelly, MES, RPA Prepared for: Karissa Kawamoto HDR, Inc. 500 108th Ave NE, Suite 1200 Bellevue, Washington 98004 Submitted by: Tierra Right of Way Services, Ltd. 2611 NE 125th Street, Suite 202 Seattle, Washington 98125 Tierra Archaeological Report No. 2013-080 March 11, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Project Information ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Regulatory Context ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Background Review .......................................................................................................................................... -

02-Grays Harbor Sediment Literature Review

Plaza 600 Building 600 Stewart Street, Suite 1700 Seattle, Washington 98101 206.728.2674 June 29, 2015 National Fisheries Conservation Center 308 Raymond Street Ojai, California 93023 Attention: Julia Sanders Subject: Cover Letter Literature Review & Support Services Grays Harbor, Washington File No. 21922-001-00 GeoEngineers has completed the literature search regarding sedimentation within Grays Harbor estuary. The attached letter report and appendices summarize our efforts to gather and evaluate technical information regarding the sedimentation conditions in Grays Harbor, and the corresponding impacts to shellfish. This literature search was completed in accordance with our signed agreement dated May 5, 2015, and is for the express use of the National Fisheries Conservation Center and its partners in this investigation. We will also provide to you electronic copies of the references contained in the bibliography. We thank you for the opportunity to support the National Fisheries Conservation Center as you investigate the sedimentation issues in Grays Harbor. We look forward to working with you to develop mitigation strategies that facilitate ongoing shellfish aquaculture in Grays Harbor. Sincerely, GeoEngineers, Inc. Timothy P. Hanrahan, PhD Wayne S. Wright, CFP, PWS Senior Fluvial Geomorphologist Senior Principal TPH:WSW:mlh Attachments: Grays Harbor Literature Review & Support Services Letter Report Figure 1. Vicinity Map Appendix A. Website Links Appendix B. Bibliography One copy submitted electronically Disclaimer: Any electronic form, facsimile or hard copy of the original document (email, text, table, and/or figure), if provided, and any attachments are only a copy of the original document. The original document is stored by GeoEngineers, Inc. and will serve as the official document of record. -

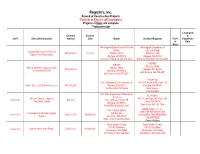

Projects *Projects in Red Are Still in Progress Projects in Black Are Complete **Subcontractor

Rognlin’s, Inc. Record of Construction Projects *Projects in Red are still in progress Projects in black are complete **Subcontractor % Complete Contract Contract & Job # Description/Location Amount Date Owner Architect/Engineer Class Completion of Date Work Washington Department of Fish and Washington Department of Wildlife Fish and Wildlife Log Jam Materials for East Fork $799,000.00 01/11/21 PO Box 43135 PO Box 43135 Satsop River Restoration Olympia, WA 98504 Olympia, WA 98504 Adrienne Stillerman 360.902.2617 Adrienne Stillerman 360.902.2617 WSDOT WSDOT PO Box 47360 SR 8 & SR 507 Thurston County PO Box 47360 $799,000.00 Olympia, WA 98504 Stormwater Retrofit Olympia, WA 98504 John Romero 360.570.6571 John Romero 360.570.6571 Parametrix City of Olympia 601 4th Avennue E. 1019 39th Avenue SE, Suite 100 Water Street Lift Station Generator $353,952.76 Olympia, WA 98501 Puyallup, WA 98374 Jim Rioux 360-507-6566 Kevin House 253.604.6600 WA State Department of Enterprise SCJ Alliance Services 14th Ave Tunnel – Improve 8730 Tallon Lane NE, Suite 200 20-80-167 $85,000 1500 Jefferson Street SE Pedestrian Safety Lacey, WA 98516 Olympia, WA 98501 Ross Jarvis 360-352-1465 Bob Willyerd 360.407.8497 ABAM Engineers, Inc. Port of Grays Harbor 33301 9th Ave S Suite 300 Terminals 3 & 4 Fender System PO Box 660 20-10-143 $395,118.79 12/08/2020 Federal Way, WA 98003-2600 Repair Aberdeen, WA 98520 (206) 357-5600 Mike Johnson 360.533.9528 Robert Wallace Grays Harbor County Grays Harbor County 100 W. -

Roadmap to a Climate Action Plan Port of Bellingham

Roadmap to a Climate Action Plan Port of Bellingham Photo by Garrett Parker on Unsplash December 31, 2019 1801 Roeder Avenue 1200 Sixth Avenue, Suite 615 Bellingham, WA 98225 Seattle, WA 98101 360-676-2500 206-823-3060 For over 40 years ECONorthwest has helped its clients make sound decisions based on rigorous economic, planning, and financial analysis. For more information about ECONorthwest: www.econw.com. ECONorthwest prepared this Roadmap to a Climate Action Plan for the Port of Bellingham. It received substantial assistance from the Port of Bellingham staff, including Adrienne Hegedus and Brian Gouran, among others. Other firms, agencies, and staff contributed to other research that this report relied on. That assistance notwithstanding, ECONorthwest is responsible for the content of this report. The staff at ECONorthwest prepared this report based on their general knowledge of urban, transportation, and natural resource planning, and on information derived from government agencies, private statistical services, the reports of others, interviews of individuals, or other sources believed to be reliable. ECONorthwest has not independently verified the accuracy of all such information and makes no representation regarding its accuracy or completeness. Any statements nonfactual in nature constitute the authors’ current opinions, which may change as more information becomes available. ECONorthwest staff who contributed to this report include Adam Domanski, Jennifer Cannon, Annalise Helm, and Sarah Reich. For more information about this report contact: Adam Domanski, Ph.D. [email protected] 1200 Sixth Avenue, Suite 615 Seattle, WA 98101 206-823-3060 ECONorthwest | Portland | Seattle | Los Angeles | Eugene | Boise | econw.com ii Table of Contents 1. -

Forests and Forest Industries Grays Harbor Unit

FORESTS AND FOREST INDUSTRIES OF THE GRAYS HARBOR UNIT FOREST ECONOMICS REPORT NUMBER 1 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE PACIFIC NORTHWEST FOREST AND RANGE EXPERIMENT STATION STEPHEN N. WYCKOFF, DIRECTOR PORTLAND, OREGON APRIL 1944 FIGURE I THE ELEVEN FOREST UNITS OF THE DOUGLAS-FIR SUBREOON 944 rIPEND WHATCOM j IJOREILLE; 1' OKANOGAN I SKAGIT 1PERRY STEVENS çJ SIVOHOMISH ,C//ELAN ) SPOKANE DOUGLAS / I IN) U/T 0 N KING LINCOLN GRANT PIERCE 3 ADAMS I / WN/TUA.Vr-' LEWIS FRANKLIN (GARP/ELD'Lj I 'L. YAK/MA I _ I ASOT/N COWLIT! L I WALLA WALLA SENTOR i Ii CLATSOF j SEAMAN/A COLUM8U KLICK/TAT p I CLARK LIMATILLA T' WALLOWA T/LLAM4 [ \ 'NG7VN k: '3 L? MORROW I, UN/ON GH(RMAN( CLACKAMAS jil GILLI.4ML., YANHILL r1i POLK MARION' I T j MAKER f LI//LOLl--------ç1 JEFFERSON WHEELER I SLI/IN r / L__ GRANT rWTON --- 1' (Th: CROOK EL1G LANE 1 DESCHUTES 1 DOUGLAS t MALNELIR LAKE HARNEY Ui W L_, CURRY I JACKSON KLAMAFN SE PH/NE J_L / C FOR.FORD The Pacific Northwest, composed of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and western Montena, has been aptly described as more strongly knit by physiographic, economic, and cultural ties than any other of the regions in the United States Recently notable progress has been made in study- ing and determining the physical, economic, and social conditions that link the population of this great region with its physical environment0 Chief among the regions ratural resources are its forest lands and forest stands. Oing to geographic differences in forest conditions, however, the region must be divided into smaller subdivisions for analy- 818of forest problems. -

Estuarine Studies in Upper Grays Harbor Washington

Estuarine Studies in Upper Grays Harbor Washington GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1873-B Prepared in cooperation with the Washington State Pollution Control Commission Estuarine Studies in Upper Grays Harbor Washington By JOSEPH P. BEVERAGE and MILTON N. SWECKER ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1873-B Prepared in cooperation with the Washington State Pollution Control Commission UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1969 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WALTER J. HICKEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 45 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract__________._._.._______._._._._.____..__..._..._ Bl Introduction. _____________________________________________________ 2 Acknowledgments _____________________________________________ 4 Previous investigations.._______________________________________ 4 Hydrology______________________________________________________ 6 Fresh water_________________________________________________ 6 Tides_____-_____--___-______--____-____---___-_____----__--__ 12 Hydraulics of the estuary._________________________________________ 16 Velocity______________________________________________________ 17 Salinity distribution.___________________________________________ 28 Dye studies_________________________________________________ 41 Summary of estuary hydraulics.________________________________ 53 Bottom materials...-__-__________-_____-____--____-______--____-__ -

Geologic Map of the Humptulips Quadrangle and Adjacent Areas

(I) GEOLOGIC MAP OF (I) I ~ C!> THE HUMPTULIPS QUADRANGLE Q. < :E AND ADJACENT AREAS, (.) C!> GRAYS HARBOR COUNTY, WASHINGTON 0 ..J 0 w C, BY WELDON W. RAU 1986 GEOLOGIC MAP GM-33 •• WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENT or ~~~=~ Natural Resources Brtan eoyi,. • C"'1lltUSSJoMt ot Publie Lands An Sleams • SupervLSOr Division ol Geology and E(rtfh Re10Utet!! Raymond LasmaN1. Sta"' Geologut Printed In the United States of America For sale by the Department of Natural Resources, Olympia, Washington Price $ 2.78 .22 tax $ 3.00 Brtw, BO\"le • Coinmis&looor <JI f>u blk; t.wxi. Ar1 Slearn< • 5ull<l,-,.•t.o,- Geologic Map WASHINGTON STATE D~ARTMENT OF Dbtl*-1 o! GeolCVI' a.-.d Earth Resource> Natural Resources RayrnoM i.,,.....,n,.. Slcrta ~~ GM-33 probably most extensive during the Oeposition of the upper part of the formatio n. Hoh rocks of this area are likely no younger than the middle Eocene Ulatisian Stage. Northern outcrops of the Montesano Formation continue westw ard from the Hoh rocks of the 00/lSlal area are known to contain foraminifers ranging in age from Wynoochee Valley quadrangle, forming a belt of ou1crop extending to the East Fork miOdlc Eocene to middle Miocene. gf the Hoquiam Rive r. The formation is ma;t extensively c,;poscd in the southeastern part of the mapped area, mainly along the Ea.st Fo rk of the Hoquiam Ri~er and along the Wishkah River and itJ lower tributaries. In aOdilion, the format ion is particularly INTRUSIVE ROCKS (Ti) well exposed in the hill s within the cities of Aberdeen and Hoquiam. -

Economic Options for Grays Harbor

ECONOMIC OPTIONS FOR GRAYS HARBOR A Report by The Evergreen State College class “Resource Rebels: Environmental Justice Movements Building Hope,” Winter 2016 CONTENTS Preface 3 Zoltán Grossman Background 6 (Lucas Ayenew, Jess Altmayer) I. Ports and Industries 12 (Roma Castellanos, Nicole Fernandez, Jennifer Kosharek) II. Tourism and Transit 27 (Jess Altmayer, Emily Hall, Megan Moore, Lauren Shanafelt) III. Forestry and Forest Products 47 (Lucas Ayenew, Kelsey Foster, Aaron Oman) IV. Fisheries and Energy 61 (Tiffany Brown, Kris Kimmel, Kyle Linden) V. Community Issues 71 (Emily Hall, Jess Altmayer) Common Themes 81 (Roma Castellanos, Emily Hall, Kelsey Foster, Kyle Linden) Background Resources 84 Evergreen students with Quinault Indian Nation Vice President Tyson Johnston (second from right) and Quinault staff members, at Quinault Department of Natural Resources in Taholah. 2 PREFACE Zoltán Grossman In January-March 2016, students from The Evergreen State College, in Olympia, Washington, studied Economic Options in Grays Harbor, looking beyond the oil terminal debate to other possibilities for job-generating development in Aberdeen, Hoquiam, and other Grays Harbor County communities. The class worked in collaboration with the Quinault Indian Nation, the Aberdeen Revitalization Movement, and community organizations. The students were part of the Evergreen program “Resource Rebels: Environmental Justice Movements Building Hope,” which explored the intersections of environmental issues with social issues of race, class, and gender. The program was taught by myself, a geographer working in Native Studies, and Karen Gaul, an anthropologist working in Sustainability Studies. In fall quarter, the class focused on Native American environmental justice issues, and hosted the 1st annual Indigenous Climate Justice Symposium at the Evergreen Longhouse, which included Quinault Indian Nation President Fawn Sharp. -

Ports in Washington State

PORTS IN WASHINGTON STATE New Market Industrial Campus and Tumwater Town Center Real Estate Development Master Plan Public Meeting #1 March 5, 2015 Founded in 2005, Community Attributes Inc. (CAI) tells data-rich stories about communities that are important to decision makers. Regional economics Land use economics Land use planning and urban design Community and economic development Surveys, market research and evaluation Data analysis and business intelligence Information design www.communityattributes.com 2 Contents 1. Ports in Washington State 2. A Port’s Purpose 3. Economic Impacts www.communityattributes.com 3 1. Ports in Washington State www.communityattributes.com 4 Ports in Washington State 75 Port districts in Washington State located in 33 of the 39 counties in Washington Port of Allyn (Mason County) Port of Grays Harbor (Grays Harbor County) Port of Poulsbo (Kitsap County) Port of Anacortes (Skagit County) Port of Hartline (Grant County) Port of Quincy (Grant County) Port of Bellingham (Whatcom County) Port of Hoodsport (Mason County) Port of Ridgefield (Clark County) Port of Benton (Benton County) Port of Illahee (Kitsap County) Port of Royal Slope (Grant County) Port of Bremerton (Kitsap County) Port of Ilwaco (Pacific County) Port of Seattle (King County) Port of Brownsville (Kitsap County) Port of Indianola (Kitsap County) Port of Shelton (Mason County) Port of Camas-Washougal (Clark County) Port of Kahlotus (Franklin County) Port of Silverdale (Kitsap County) Port of Centralia (Lewis County) Port of Kalama (Cowlitz -

Ninth Amendment to Fmc Agreement No. 009335 the Marine Terminal Discussion Agreement and Cooperative Working Agreement for the N

NINTH AMENDMENT TO FMC AGREEMENT NO. 009335 THE MARINE TERMINAL DISCUSSION AGREEMENT AND COOPERATIVE WORKING AGREEMENT FOR THE NORTHWEST MARINE TERMINAL ASSOCIATION THIS NINTH AMENDMENT is made and entered into as of .~ ~ 7 , 2016, to FMC Agreement No. 009335, the Marine Terminal Discussion Agreement and Cooperative Working Agreement for the Northwest Marine Terminal Association ("Agreement"). WHEREAS, Article ?(a) of the Agreement states that "Any public or private terminal operator serving interstate and foreign commerce and located within the States of Oregon or Washington shall be eligible to become a Member of this Agreement, upon consent of the majority of the membership, by affixing its signature thereto; and WHEREAS, the Northwest Seaport Alliance ("Alliance") has applied for membership and the Northwest Marine Terminal Association ("NWMTA") fTl e~mbers voted and approved in accordance with the applicable procedures on 4 l£ ,2016, to have the Alliance join the NWMTA; and WHEREAS, Article ?(d) of the Agreement states that "Prompt notice of admission to membership shall be furnished to the Federal Maritime Commission and such admission shall be effective upon the filing of a modification with the Commission"; and WHEREAS, the Port ofTacoma, a member of the NWMT A, has transferred management of its cargo terminals to the Alliance and will have its interests represented adequately by the Alliance and therefore desires to relinquish its membership in the NWMTA; NOW THEREFORE, 1 . The Northwest Seaport Alliance is approved as a new member of NWMTA. A revised Page 20 and 21 is added to Agreement No. 009335-009 showing the Northwest Seaport Alliance as a member of the NWMTA.