Gerulata: the Lamps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exhibition DL in Slovakia Description

Exhibition Danube Limes in Slovakia – Ancient Roman Monuments on the Middle Danube © Monuments Board of the Slovak Republic Cesta na Červený most 6 814 06 Bratislava Slovak Republic Cooperation: Bratislava City Museum and Archeological Institute SAV, Nitra Authors: Ľubica Pinčíková, Jaroslava Schmidtová, Anna Tuhárska, Ján Rajtár Aim of the exhibition is to present the site Danube Limes in Slovakia – Ancient Roman Monuments on the Middle Danube, currently prepared for nomination on the UNESCO World Heritage List. The site was part of a vast system of frontiers of the Roman Empire, which were formed in this part of Europe by the river Danube. An ingenious system of the Roman frontiers in the framework of a river border is documented in the territory of Slovakia by two Roman forts – Roman Military Camp (Fort) Gerulata in Bratislava - Rusovce and Roman Military Camp (Fort) in Iža – “Kelemantia“ which are introduced by this exhibition. It informs about their values, historical development and the history of their discovery through archaeological research. The exhibition also presents the broader context of the frontiers of the Roman Empire in Europe as well as the hinterland of both forts. The exhibition was prepared within the framework of the project Danube Limes – UNESCO World Heritage, No. 1CE079P4 implemented through the Central Europe Programme and co-financed by the ERDF. Opening of the exhibition took place on 19th April 2012 at the Museum Gerulata in Rusovce, in the presence of the President of the Slovak Republic, Mr. Ivan Gašparovič. The exhibition consists of 7 banners of 100 x 145 cm. List of banners: 1. -

Gerulata the Lamps

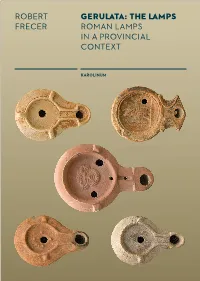

ROMANLAMPSINAPROVINCIALCONTEXT THE LAMPS GERULATA: ROBERTFRECER What should a catalogue of archaeological material contain? ROBERT This book is a comprehensive index of 210 lamps from the GERULATA: THE LAMPS Roman fort of Gerulata (present-day Bratislava-Rusovce, FRECER ROMANLAMPS Slovakia) and its adjoining civilian settlement. The lamps were excavated during the last 50 years from the houses, INAPROVINCIAL cemeteries, barracks and fortifi cations of this Roman outpost on the Limes Romanus and span almost three centuries from CONTEXT ad 80 to ad 350. For the fi rst time, they are published in full and in color with detailed analysis of lamp types, workshop marks and discus scenes. Roman lamps were a distinctive form of interior lighting that KAROLINUM burned liquid fuel seeped through a wick to create a controlled fl ame. Relief decorations have made them appealing objects of minor art in modern collections, but lamps were far more than that – with a distribution network spanning three continents, made by a multitude of producers and brands, with their religious imagery depicting forms of worship, and as symbols of study and learning, Roman lamps are an eff ective tool that can be used by the modern scholar to discover the ancient economy, culture, cra organization and Roman provincial life. frecer_gerulata_mont.indd 1 6/4/15 9:59 PM Gerulata: The Lamps Roman Lamps in a Provincial Context Robert Frecer Reviewers: Laurent Chrzanovski Florin Topoleanu Published by Charles University in Prague Karolinum Press Layout by Jan Šerých Typeset by Karolinum Press Printed by PBtisk First edition This work drew financial support from grant no. -

D4 Jarovce – Ivanka North

GEOCONSULT, spol. s r.o. engineering - design and consulting company, Miletičova 21, P.O.Box 34, 820 05 Bratislava 25 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Protected areas in terms of water management According to Annex 1 to the Regulation of the Ministry of Agriculture of the Slovak Republic No. 211/2005 Coll. setting the list of significant water supply streams, the Danube and the Little Danube river are included in the list of significant water supply streams. Number Water flow significant for water management Number Name of hydrological border in the section (km) catchment area in the section (km) 69. Danube 4-20-01-001 - 1708.02-1850.2 and 1872.7-1880.2 72. Little Danube 4-20-01-010 all the section - 293. Šúrsky channel 4-21-15-005 all the section The Danube river with its system of branches represents the predominant factor in creation of the supplies and quality of ground water. The Danube gravel alluvia are a significant reservoir of ground water and they represent the biggest accumulation of ground water in Central Europe. The main source of ground water is the infiltrated water of the Danube, while the greatest sources of drinking water are located in the alluvial zone of the river. For the above reason, this territory is protected by law and it entire belongs to the significant water supply area of PWA (protected water area) Žitný ostrov. Protected water management area of Žitný ostrov has an area of nearly 1,400 km2, however, it represents only about 20% of the total area (about 7,000 km2) of all PWMA in Slovakia. -

Archeologia 2013 Layout 1

ZBORNÍK SLOVENSKÉHO NÁRODNÉHO MÚZEA CVII – 2013 ARCHEOLÓGIA 23 ROMAN LAMPS OF GERULATA AND THEIR ROLE IN FUNERAL RITES ROBERT FRECER Keywords: Roman lamps, Gerulata, cemetery, burial, funeral rites, Firmalampen Abstract: The auxiliary camp of Gerulata was founded in the late Flavian period, and housed a cavalry ala for most of its existence. Its adjoining cemeteries contained Roman lamps as a major group of grave goods, in both cremation and inhumation graves until the early 3rd century AD, when lamps ceased to be deposited. Altogether 93 graves out of 336 contained a total of 106 lamps, a largely 2nd century assembly of both Firma- and Bildlampen. Lamps played a part in funeral rites, usually to be burned on the pyre; at Gerulata they were second only to pottery in abundance though they occur in varying proportion across different cemeteries and burial types. Their context in burial practice and relationship with other grave goods is analysed throughout; notably, adult inhumation graves seem to purposely lack lamps. The lamps bear signs of use, personal ownership, and several unique relief stamps and inscriptions, but the proportion of imports to locally made lamps remains uncertain. Roman lamps in Gerulata are seen as tokens of Roman culture, much used by the inhabitants of this borderland settlement in both life and death. As the Danube River passes from the banks of Carnuntum under the rocky slopes of Devín and Hainburg and through the natural water gate formed by these two hilltops, it widens and bends to the southwest, in anticipation of the marshy and manifold currents that give rise to the Greater and Lesser Rye Islands (Veľký a Malý Žitný ostrov). -

A Római Birodalom Határai Frontiers of the Roman Empire David J

A RÓMAI BIRODALOM HATÁRAI FRONTIERS OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE DAVID J. BREEZE – SONJA JILEK - ANDREAS THIEL A RÓMAI LIMES MAGYARORSZÁGON THE ROMAN LIMES IN HUNGARY VISY ZSOLT Támogató: CENTRAL EUROPE PROGRAM PTE Régészet Tanszék Pécs, 2009. Előlap/Front cover: erődkapu cserépmodellje Intercisából/Clay model of a gate of a fort from Intercisa Hátlap/Back cover: Az Antoninus Falról (Skócia, UK) származó felirat, amelyik a limes egy szakaszának a megépítéséről tájékoztat/An inscription from the Antonine Wall (Scotland, UK) recording the construction of a section of the frontier Copyright © by Historic Scotland, UK; Deutsche Limeskommission, Germany, Pécsi Tudományegyetem Régészet Tanszék Kiadó/edited by Zsolt Visy Fordítás/translation by Zsuzsa Katona Győr Nyelvhelyességi szempontból ellenőrizte: Dr. Fülep Ferencné és Fülep Zsófia Szerkesztés/designed by Krisztián Kolozsvári A 2. javított kiadás a Central Europe Program, Danube Limes pályázatának keretében valósult meg Nyomda/printed by Bornus 2009 Nyomda, Pécs Pécs 2009 ISBN 978-963-642-234-9 Tartalom CONTENTS A Római Birodalom határai ����������������������������� 5 Frontiers of the Roman Empire ����������������������� 5 A római limes Magyarországon ��������������������� 35 The Roman limes in Hungary ����������������������� 35 Szakirodalmi tájékoztató ������������������������������� 79 Further Reading ������������������������������������������� 79 A képek forrása . 82 Illustration acknowledgments . 82 Rövidítések . 83 Abbreviations ����������������������������������������������� 83 A RÓMAI Birodalom -

XXIII. Limes Congress 2015

XXIII. Limes Congress 2015 Abstracts of Lectures and Posters List of Participants Abstracts of Lectures Inhalt Fawzi Abudanah, Via Nova Traiana between Petra and Ayn al-Qana in Arabia Petraea .................... 10 Cristina-Georgeta Alexandrescu, Not just stone: Building materials used for the fortifications in the area of Troesmis (Turcoaia, Tulcea County, RO) and its territorium (second to fourth century AD) ... 11 Cristina Georgeta Alexandrescu, Signaling in the army ...................................................................... 11 Ignacio Arce, Severan Castra, Tetrarchic Quadriburgia, Ghassanid Diyarat: Patterns of Transformation of Limes Arabicus Forts during Late Antiquity ............................................................ 12 Martina Back, Brick fabrication ............................................................................................................ 14 Gereon Balle/Markus Scholz. The monumental building beside the fort of the ala II Flavia milliaria in Aquileia/Heidenheim – Public baths or administrative building of the provincial government? (Raetia) .............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Thomas Becker/Ayla Jung, Unusual building structures in the vicus of Inheiden (Germania Superior) .............................................................................................................................................................. 15 Thomas Becker, Der Pfeilerbau im -

Limes Romanus in Slovakia

13 th International Congress „Cultural Heritage and New Technologies“ Vienna, 2008 Limes Romanus in Slovakia Jaroslava SCHMIDTOVÁ / Ján RAJTÁR / Katarína HARMADYOVÁ Abstract: During the Roman period the major part of contemporary Slovakia lied outside the territory of the Roman Empire. Only its very small area on the right bank of the river Danube – fore field of the present capital Bratislava – belonged to the province Pannonia Superior. On the Danube, south- western Slovakia had a very close connection with the northpannonian frontier, however, and such a close neighbourhood had a significant impact on the development in their fore field, too. The permanent military camps on limes started to be built only under Domitian (81 – 96). During his era limes castel Gerulata (village Rusovce, contemporary suburb of Bratislava) situated southwest of Carnuntum was founded by Romans. Another Roman castle was situated nearby village Iža by Komárno. It originated later, under Marcus Aurelius (161 – 180) and as the only fortress in this segment of limes it was pushed forward to the left bank of the Danube. On the territory of the southwestern Slovakia were many architectures built in Roman style but in the Germanic environment uncovered. The oldest traces of such architectures go back to the era of Augustus and they were unearthed above the confluence of the rivers Danube and Morava in Bratislava-Devín. Other similar buildings from Stupava, Bratislava-Dúbravka, Cífer-Pác, Ve ľký Kýr (before Milanovce) and from Bratislava-Devín belong already to the 2nd, 3rd and the late 4th century. Three sites on Limes Romanus in Slovakia are three National Cultural Monuments - Devín, Gerulata and Iža. -

ARCH D3.3 City Baseline Report - Bratislava

ARCH D3.3 City baseline report - Bratislava 29 April 2020 Deliverable No. D3.3 Work Package WP3 Dissemination Level PU Author(s) Eva Streberova (Bratislava City) Simona Klacanova, Monika Steflovicova (Bratislava City) Margareta Musilova (MUOP) Eva Pauditsova (UNIBA) Co-Author(s) Serene Hanania (ICLEI) Daniel Lückerath, Katharina Milde (Fraunhofer) Sonia Giovinazzi, Ludovica Giordano (ENEA) Due date 2020-03-31 Actual submission date 2020-04-30 Status For submission Revision 1 Rene Lindner, Anne-Kathrin Schäfer (DIN); Eleanor Reviewed by (if applicable) Chapman, Iryna Novak (ICLEI); Artur Krukowski (RFSAT) This document has been prepared in the framework of the European project ARCH – Advancing Resilience of historic areas against Climate-related and other Hazards. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 820999. The sole responsibility for the content of this publication lies with the authors. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the European Union. Neither the EASME nor the European Commission are responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. Contact [email protected] www.savingculturalheritage.eu This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement no. 820999. 2 ARCH D3.3 City baseline report - Bratislava Table of Contents 1. City Profile .................................................................................................................. -

Gerulata the Lamps

ROMANLAMPSINAPROVINCIALCONTEXT THE LAMPS GERULATA: ROBERTFRECER What should a catalogue of archaeological material contain? ROBERT This book is a comprehensive index of 210 lamps from the GERULATA: THE LAMPS Roman fort of Gerulata (present-day Bratislava-Rusovce, FRECER ROMANLAMPS Slovakia) and its adjoining civilian settlement. The lamps were excavated during the last 50 years from the houses, INAPROVINCIAL cemeteries, barracks and fortifi cations of this Roman outpost on the Limes Romanus and span almost three centuries from CONTEXT ad 80 to ad 350. For the fi rst time, they are published in full and in color with detailed analysis of lamp types, workshop marks and discus scenes. Roman lamps were a distinctive form of interior lighting that KAROLINUM burned liquid fuel seeped through a wick to create a controlled fl ame. Relief decorations have made them appealing objects of minor art in modern collections, but lamps were far more than that – with a distribution network spanning three continents, made by a multitude of producers and brands, with their religious imagery depicting forms of worship, and as symbols of study and learning, Roman lamps are an eff ective tool that can be used by the modern scholar to discover the ancient economy, culture, cra organization and Roman provincial life. U k á z k a k n i h y z i n t e r n e t o v é h o k n i h k u p e c t v í w w w . k o s m a s . c z , U I D : K O S 2 0 8 3 8 0 frecer_gerulata_mont.indd 1 6/4/15 9:59 PM Gerulata: The Lamps Roman Lamps in a Provincial Context Robert Frecer Reviewers: Laurent Chrzanovski Florin Topoleanu Published by Charles University in Prague Karolinum Press Layout by Jan Šerých Typeset by Karolinum Press Printed by PBtisk First edition This work drew financial support from grant no. -

Danube Limes in Slovakia. Ancient Roman Monuments on the Middle Danube. Printed Final Document to Nominate

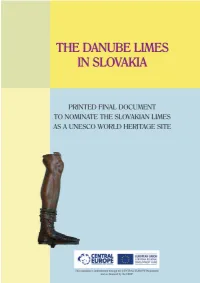

Danube Limes in Slovakia – Ancient Roman Monuments on the Middle Danube NOMINATION FOR INSCRIPTION OF THE PROPERTY ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST DANUBE LIMES IN SLOVAKIA - ANCIENT ROMAN MONUMENTS ON THE MIDDLE DANUBE exte nsion of the Frontiers of the Roman Empire World Heritage Site MONUMENTS BOARD OF THE SLOVAK REPUBLIC Cesta na Červený most 6, 814 06 Bratislava, Slovak Republic 2011 2 Danube Limes in Slovakia – Ancient Roman Monuments on the Middle Danube CONTENTS A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY B. NOMINATION FORMAT 1. Identification of the Property 1.a Country 1.b State, Province or Region 1.c Name of Property 1.d Geographical coordinates 1.e Maps and plans, showing the boundaries of the nominated property and buffer zone 1.f Area of nominated property and proposed buffer zone 2. Description 2.a Description of Property 2.a/1 Frontier of the Roman Empire – Limes Romanus 2.a/2 Danube Limes 2.a/3 Danube Limes in Slovakia – Ancient Roman Monuments on the Middle Danube 2.b History and Development 2.B.a Danube Limes 2.B. b Danube Limes in Slovakia – Ancient Roman Monuments on the Middle Danube 2.B.c Roman Military Camp (Fort) Gerulata in Bratislava - Rusovce 2.B.d. Roman Military Camp (Fort) in Iža – "Kelemantia" 3. Justification for Inscription 3.a Criteria under which inscription is proposed (and justification for inscription under these criteria) 3 Danube Limes in Slovakia – Ancient Roman Monuments on the Middle Danube 3.b Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.c Comparative analysis 3.d Integrity and/or Authenticity 4. -

Limes Romanus – Roman Antique Monuments on the Middle Danube Ľubica Pin Číková

Limes Romanus – Roman Antique Monuments on the Middle Danube Ľubica Pin číková Expansion of the Roman Empire contributed to an incorporation of today south- east Slovakia into an European context of historical events in period of 1 st -4th century. Northern natural border of the empire and its Panonia province in the area was formed by Danube River. Along the river Romans gradually constructed large border system of fortresses, so called Limes Romanus. It also contained a military fortress in Iža and in Bratislava– Rusovce. Both localities represent typical types of camps on Roman border. However, Kelemantia castle in Iža, created as bridgehead of camp of legions and civil town of Brigetio is one of the largest Roman building complexes in barbaricum. It is a proof of long-term military presence of Romans on northern side of Danube. In 3rd century the castle was hardly impaired and reconstructed. It did not lose an importance even in 4th century. The area is currently registered as cultural archaeological memory started to be unoccupied from 5th century only. Foto Ľ. Pin číková Roman castle Gerulata in Bratislava– Rusovce was first in the Carnuntum– Ad Flexum line. Discovered stelas and fragments of tombs can be seen as considerable proof of richness and extensive settlement of Gerulata from the end of the 1st century to the beginning of the 3rd century. Continuity of the occupation from older Bronze Age up to construction of castle by Romans is a proof of an extraordinary importance of the locality. After a fall of Roman power ruins of complex residential unit of Gerulata were occupied by Goths, followed by Slavs. -

New Finds of Roman Rings from a Rich Grave in Cemetery III, Rusovce‑Gerulata

STUDIA HERCYNIA XX/1, 83–99 New Finds of Roman Rings from a Rich Grave in Cemetery III, Rusovce ‑Gerulata Jaroslava Schmidtová – Miroslava Daňová – Alena Šefčáková ACbsTRA T In 2014 a unique burial was unearthed in Gerulata cemetery III, containing an unusual number of rings. The buried woman aged 40–49 had two rings on each hand, one of which was a signet ring with a gem depicting the Egyptian deities Serapis and Isis. Another unusual item was a bracelet composed of seven disks with side openings for a string. Two glazed vessels have enlarged the number of known vessels of this type from this site to 13 pieces. KOEYW Rds Gerulata; Roman period; burial; finger ring; gem; Isis; Serapis; glazed vessels; anthropological analysis. INTRODUCTION FIND circumstances During the archaeological excavation at Rusovce in 2014, conducted by Bratislava City Museum on a house construction site, plot no. 743/1, we unearthed the continuation of cemetery III. Two structures were studied in a utility trench: a settlement structure situated almost in the back ‑yard of the plot, 27–28 m from the street; and an inhumation grave situated 8–9 m from the street (Fig. 1–2). The studied site is situated in the south ‑western part of Rusovce, on the Kovácsova Street, around 170 m from the overhead water tank (cemetery II) and today’s cem‑ etery in Rusovce, and south ‑west of the Gerulata fort (Fig. 1). History OF excavations We know from previous excavations that Radnóti’s site VI, where he examined nine cremation and inhumation graves, lay on today’s plot 736, the former ‘Acker Denk’ or Mr.