7 Contents Studies and Articles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Mentality and Researcher Thinkers Journal

SOCIAL MENTALITY AND RESEARCHER THINKERS JOURNAL Open Access Refereed E-Journal & Refereed & Indexed ISSN: 2630-631X Social Sciences Indexed www.smartofjournal.com / [email protected] September 2017 Article Arrival Date: 09.06.2017 Published Date: 30.09.2017 Vol 3 / Issue 6 / pp: 63-67 Opportunities And Prospects For Deveiopment Of Ecoiogical Tourism In Kazakhstan Jumakan Makanovich ARYNOV Kazakh State Women’s Teacher Training University, Kazakhstan Raisa Sanakovna SAURBAEVA Kazakh State Women’s Teacher Training University, Kazakhstan Saule Mustafakyzy SYZDYKOVA Kazakh State Women’s Teacher Training University, Kazakhstan ABSTRACT The authors analyzed the diplomatic practice of the Kazakh Khanate and independent Kazakhstan. Based on the works Kussainova A. and Gusarova A. try to describe the main diplomatic actors – the khans, sultans, biys, diplomats and the First President of sovereign Kazakhstan NursultanNazarbayev – which in their foreign-policy activity were used such diplomatic methods as the conclusion of inter-dynasty marriages, the use of interstate and intrastate conflicts, searching and finding allies, representation of amanats in the past and establish economical and political agreements, held multi- vector policy in nowadays. Key Words: The khans, sultans, biys, amanat, agreement. Kazakhstan's diplomacy has deep historical roots. “Steppe diplomacy dressed in tails” – this phrase emphasizes both the old and the young nature of the Kazakh diplomacy [1, p.27]. Since the second half of the XV century on the stage of history goes independent Kazakh feudal-patriarchal state. Diplomatic practice of the Kazakh Khanate not initially relied extensively on the forms and methods of the rich arsenal of predecessors – the ancient Turks and the Golden Horde [2, p.66]. -

Steppe Nomads in the Eurasian Trade1

Volumen 51, N° 1, 2019. Páginas 85-93 Chungara Revista de Antropología Chilena STEPPE NOMADS IN THE EURASIAN TRADE1 NÓMADAS DE LA ESTEPA EN EL COMERCIO EURASIÁTICO Anatoly M. Khazanov2 The nomads of the Eurasian steppes, semi-deserts, and deserts played an important and multifarious role in regional, interregional transit, and long-distance trade across Eurasia. In ancient and medieval times their role far exceeded their number and economic potential. The specialized and non-autarchic character of their economy, provoked that the nomads always experienced a need for external agricultural and handicraft products. Besides, successful nomadic states and polities created demand for the international trade in high value foreign goods, and even provided supplies, especially silk, for this trade. Because of undeveloped social division of labor, however, there were no professional traders in any nomadic society. Thus, specialized foreign traders enjoyed a high prestige amongst them. It is, finally, argued that the real importance of the overland Silk Road, that currently has become a quite popular historical adventure, has been greatly exaggerated. Key words: Steppe nomads, Eurasian trade, the Silk Road, caravans. Los nómadas de las estepas, semidesiertos y desiertos euroasiáticos desempeñaron un papel importante y múltiple en el tránsito regional e interregional y en el comercio de larga distancia en Eurasia. En tiempos antiguos y medievales, su papel superó con creces su número de habitantes y su potencial económico. El carácter especializado y no autárquico de su economía provocó que los nómadas siempre experimentaran la necesidad de contar con productos externos agrícolas y artesanales. Además, exitosos Estados y comunidades nómadas crearon una demanda por el comercio internacional de bienes exóticos de alto valor, e incluso proporcionaron suministros, especialmente seda, para este comercio. -

Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov

SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV CHOKAN OF WORKS SELECTED SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV Pioneering Ethnographer and Historian of the Great Steppe When Chokan Valikhanov died of tuberculosis in 1865, aged only 29, the Russian academician Nikolai Veselovsky described his short life as ‘a meteor flashing across the field of oriental studies’. Set against his remarkable output of official reports, articles and research into the history, culture and ethnology of Central Asia, and more important, his Kazakh people, it remains an entirely appropriate accolade. Born in 1835 into a wealthy and powerful Kazakh clan, he was one of the first ‘people of the steppe’ to receive a Russian education and military training. Soon after graduating from Siberian Cadet Corps at Omsk, he was taking part in reconnaissance missions deep into regions of Central Asia that had seldom been visited by outsiders. His famous mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, which began in June 1858 and lasted for more than a year, saw him in disguise as a Tashkent mer- chant, risking his life to gather vital information not just on current events, but also on the ethnic make-up, geography, flora and fauna of this unknown region. Journeys to Kuldzha, to Issyk-Kol and to other remote and unmapped places quickly established his reputation, even though he al- ways remained inorodets – an outsider to the Russian establishment. Nonetheless, he was elected to membership of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and spent time in St Petersburg, where he was given a private audience by the Tsar. Wherever he went he made his mark, striking up strong and lasting friendships with the likes of the great Russian explorer and geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tian-Shansky and the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. -

2 Trade and the Economy(Second Half Of

ISBN 92-3-103985-7 Introduction 2 TRADE AND THE ECONOMY(SECOND HALF OF NINETEENTH CENTURY TO EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY)* C. Poujol and V. Fourniau Contents Introduction ....................................... 51 The agrarian question .................................. 56 Infrastructure ...................................... 61 Manufacturing and trade ................................ 68 Transforming societies ................................. 73 Conclusion ....................................... 76 Introduction Russian colonization in Central Asia may have been the last phase of an expansion of the Russian state that had begun centuries earlier. However, in terms of area, it represented the largest extent of non-Russian lands to fall under Russian control, and in a rather short period: between 1820 (the year of major political and administrative decisions aimed at the Little and Middle Kazakh Hordes, or Zhuzs) and 1885 (the year of the capture of Merv). The conquest of Central Asia also brought into the Russian empire the largest non-Russian population in an equally short time. The population of Central Asia (Steppe and Turkistan regions, including the territories that were to have protectorate status forced on them) was 9–10 million in the mid-nineteenth century. * See Map 1. 51 ISBN 92-3-103985-7 Introduction Although the motivations of the Russian empire in conquering these vast territories were essentially strategic and political, they quickly assumed a major economic dimension. They combined all the functions attributed by colonial powers -

CENTRE for EAST EUROPEAN STUDIES University of Warsaw

CENTRE FOR EAST EUROPEAN STUDIES University of Warsaw The Centre’s mission is to prepare young, well-educated and skilled specialists in Eastern issues from Poland and other countries in the region, for the purposes of academia, the nation and public service... 1990-2015 1990-2015 ORIGINS In introducing the history of Eastern Studies in Poland – which the modern day Centre for EASTERN INSTITUTE IN WARSAW (1926-1939) East European Studies UW is rooted in – it is necessary to name at least two of the most im- portant Sovietological institutions during the inter-war period. Te Institute’s main task was ideological development of young people and propagating the ideas of the Promethean movement. Te Orientalist Youth Club (established by Włodzimierz Bączkowski and Władysław Pelc) played a signifcant part in the activation of young people, especially university students. Lectures and publishing activity were conducted. One of the practical tasks of the Institute was to prepare its students for the governmental and diplomatic service in the East. Te School of Eastern Studies operating as part of the Institute was regarded as the institution to provide a comprehensive training for specialists in Eastern issues and languages. Outstanding specialists in Eastern and Oriental studies shared their knowledge with the Insti- tute’s students, among them: Stanisław Siedlecki, Stanisław Korwin-Pawłowski, Ryochu Um- eda, Ayaz Ischaki, Witold Jabłoński, Hadżi Seraja Szapszał, Giorgi Nakashydze and others. Jan Kucharzewski (1876-1952), Cover of the “Wschód/Orient” chairman of the Eastern Institute journal published by the Eastern in Warsaw, author of the 7-volume Institute in Warsaw, editor-in- work “Od białego caratu do chief W. -

Intern Announcement

INTERN ANNOUNCEMENT EMBASSY OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BAKU No. BAKU- Public Affairs Section Intern Date: 2019-I-11 10/21/2019 OPEN TO: All Azerbaijan Citizen University Students POSITION: Public Affairs Section Intern OPENING DATE: October 21, 2019 CLOSING DATE: November 04, 2019 WORK HOURS: Part time; 20-30 hours/week LENGTH OF HIRE: Six months IMPORTANT NOTICE: This is NOT an offer of Federal Employment; There will be NO benefits; There will be NO COMPENSATION. Note: All information and statement submitted for an internship vacancy are subject to verification. Any willful misstatement will result in elimination for internship consideration and if the individual is hired, subject to immediate termination irrespective of the length of internship. The U.S. Embassy in Baku is seeking individuals for a Public Affairs Section Intern position. Multiple selections may be made from this announcement. BASIC FUNCTION OF THE POSITION The incumbent assist with a variety of cultural and educational projects and outreach. Intern will assist with the all aspects of Embassy exchange programs including notifying applicants and reviewing applications, will assist with organizing public outreach events and programs, helps to coordinate logistical and promotional details for visiting speaker programs and other duties as assigned. A copy of the complete position description listing all duties and responsibilities is available in the Human Resources Office. Contact ext. 3847. QUALIFICATIONS REQUIRED NOTE: All applicants must address each selection criteria detailed below with specific and comprehensive information supporting each item. 1. EDUCATION: Current undergraduate or graduate student study is required. 2. LANGUAGE: Level III (Good working knowledge) Speaking/Reading/Writing English is required. -

1Daskalov R Tchavdar M Ed En

Entangled Histories of the Balkans Balkan Studies Library Editor-in-Chief Zoran Milutinović, University College London Editorial Board Gordon N. Bardos, Columbia University Alex Drace-Francis, University of Amsterdam Jasna Dragović-Soso, Goldsmiths, University of London Christian Voss, Humboldt University, Berlin Advisory Board Marie-Janine Calic, University of Munich Lenard J. Cohen, Simon Fraser University Radmila Gorup, Columbia University Robert M. Hayden, University of Pittsburgh Robert Hodel, Hamburg University Anna Krasteva, New Bulgarian University Galin Tihanov, Queen Mary, University of London Maria Todorova, University of Illinois Andrew Wachtel, Northwestern University VOLUME 9 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsl Entangled Histories of the Balkans Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies Edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover Illustration: Top left: Krste Misirkov (1874–1926), philologist and publicist, founder of Macedo- nian national ideology and the Macedonian standard language. Photographer unknown. Top right: Rigas Feraios (1757–1798), Greek political thinker and revolutionary, ideologist of the Greek Enlightenment. Portrait by Andreas Kriezis (1816–1880), Benaki Museum, Athens. Bottom left: Vuk Karadžić (1787–1864), philologist, ethnographer and linguist, reformer of the Serbian language and founder of Serbo-Croatian. 1865, lithography by Josef Kriehuber. Bottom right: Şemseddin Sami Frashëri (1850–1904), Albanian writer and scholar, ideologist of Albanian and of modern Turkish nationalism, with his wife Emine. Photo around 1900, photo- grapher unknown. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Entangled histories of the Balkans / edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov. pages cm — (Balkan studies library ; Volume 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Politics of Titular Identity and State- Legitimization: the Unique Case of Post- Colonial and Post-Communist Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan

The University of Chicago Politics of Titular Identity and State- Legitimization: The Unique Case of Post- Colonial and Post-Communist Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan By Zhanar Irgebay July 2021 A paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Masters of Arts degree in the Master of Arts Program in the Committee on International relations Faculty Advisor: Russel Zanca Preceptor: Nick Campbell-Seremetis Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Methodology…...………………………………………………………………………………….5 Literature Review………………………………………………………………………………….6 Historical Background…………………………………………………………………………….9 Case Analysis…………………………………………………………………………………….16 Post-Communist Nation-Building; Neo-Patrimonial and Clan Politics…………………18 Post-Colonial Nation-Building and Naturalization Policies……………………………..21 Connection to pre-Russian Empire………………………………………………………24 Politics of Religion………………………………………………………………………26 Politics of Language……………………………………………………………………..27 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………….29 References………………………………………………………………………………………..32 Figures Figure 1. Population of Kazakh Autonomous Social Soviet Republic based on Major Ethnic Groups in 1926…………………………………………………9 Figure 2. Population of Kazakh Autonomous Social Soviet Republic based on Major Ethnic Groups in 1989……………………………………………..…10 Figure 3. Population of Kyrgyz Autonomous Social Soviet Republic based on Major Ethnic Groups in 1926………………………………………………..11 Figure 4. Population of Kyrgyz Autonomous Social Soviet Republic based on Major Ethnic Groups -

The Balkan Vlachs/Aromanians Awakening, National Policies, Assimilation Miroslav Ruzica Preface the Collapse of Communism, and E

The Balkan Vlachs/Aromanians Awakening, National Policies, Assimilation Miroslav Ruzica Preface The collapse of communism, and especially the EU human rights and minority policy programs, have recently re-opened the ‘Vlach/Aromanian question’ in the Balkans. The EC’s Report on Aromanians (ADOC 7728) and its separate Recommendation 1333 have become the framework for the Vlachs/Aromanians throughout the region and in the diaspora to start creating programs and networks, and to advocate and shape their ethnic, cultural, and linguistic identity and rights.1 The Vlach/Aromanian revival has brought a lot of new and reopened some old controversies. A increasing number of their leaders in Serbia, Macedonia, Bulgaria and Albania advocate that the Vlachs/Aromanians are actually Romanians and that Romania is their mother country, Romanian language and orthography their standard. Such a claim has been officially supported by the Romanian establishment and scholars. The opposite claim comes from Greece and argues that Vlachs/Aromanians are Greek and of the Greek culture. Both countries have their interpretations of the Vlach origin and history and directly apply pressure to the Balkan Vlachs to accept these identities on offer, and also seek their support and political patronage. Only a minority of the Vlachs, both in the Balkans and especially in the diaspora, believes in their own identity or that their specific vernaculars should be standardized, and that their culture has its own specific elements in which even their religious practice is somehow distinct. The recent wars for Yugoslav succession have renewed some old disputes. Parts of Croatian historiography claim that the Serbs in Croatia (and Bosnia) are mainly of Vlach origin, i.e. -

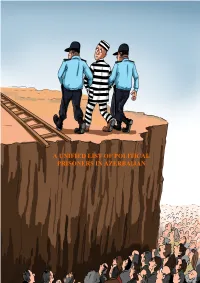

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested -

Zhanat Kundakbayeva the HISTORY of KAZAKHSTAN FROM

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF THE REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN THE AL-FARABI KAZAKH NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Zhanat Kundakbayeva THE HISTORY OF KAZAKHSTAN FROM EARLIEST PERIOD TO PRESENT TIME VOLUME I FROM EARLIEST PERIOD TO 1991 Almaty "Кazakh University" 2016 ББК 63.2 (3) К 88 Recommended for publication by Academic Council of the al-Faraby Kazakh National University’s History, Ethnology and Archeology Faculty and the decision of the Editorial-Publishing Council R e v i e w e r s: doctor of historical sciences, professor G.Habizhanova, doctor of historical sciences, B. Zhanguttin, doctor of historical sciences, professor K. Alimgazinov Kundakbayeva Zh. K 88 The History of Kazakhstan from the Earliest Period to Present time. Volume I: from Earliest period to 1991. Textbook. – Almaty: "Кazakh University", 2016. - &&&& p. ISBN 978-601-247-347-6 In first volume of the History of Kazakhstan for the students of non-historical specialties has been provided extensive materials on the history of present-day territory of Kazakhstan from the earliest period to 1991. Here found their reflection both recent developments on Kazakhstan history studies, primary sources evidences, teaching materials, control questions that help students understand better the course. Many of the disputable issues of the times are given in the historiographical view. The textbook is designed for students, teachers, undergraduates, and all, who are interested in the history of the Kazakhstan. ББК 63.3(5Каз)я72 ISBN 978-601-247-347-6 © Kundakbayeva Zhanat, 2016 © al-Faraby KazNU, 2016 INTRODUCTION Данное учебное пособие is intended to be a generally understandable and clearly organized outline of historical processes taken place on the present day territory of Kazakhstan since pre-historic time. -

Elements of Romanian Spirituality in the Balkans – Aromanian Magazines and Almanacs (1880-1914)

SECTION: JOURNALISM LDMD I ELEMENTS OF ROMANIAN SPIRITUALITY IN THE BALKANS – AROMANIAN MAGAZINES AND ALMANACS (1880-1914) Stoica LASCU, Associate Professor, PhD, ”Ovidius” University of Constanța Abstract: Integral parts of the Balkan Romanian spirituality in the modern age, Aromanian magazines and almanacs are priceless sources for historians and linguists. They clearly shape the Balkan dimension of Romanism until the break of World War I, and present facts, events, attitudes, and representative Balkan Vlachs, who expressed themselves as Balkan Romanians, as proponents of Balkan Romanianism. Frăţilia intru dreptate [“The Brotherhood for Justice”]. Bucharest: 1880, the first Aromanian magazine; Macedonia. Bucharest: 1888 and 1889, the earliest Aromanian literary magazine, subtitled Revista românilor din Peninsula Balcanică [“The Magazine of the Romanians from the Balkan Peninsula”]; Revista Pindul (“The Pindus Magazine”). Bucharest: 1898-1899, subtitled Tu limba aromânească [“In Aromanian Language”]; Frăţilia [“The Brotherhood”]. Bitolia- Buchaerst: 1901-1903, the first Aromanian magazine in European Turkey was published by intellectuals living and working in Macedonia; Lumina [“The Light”]: Monastir/Bitolia- Bucharest: 1903-1908, the most long-standing Aromanian magazine, edited in Macedonia, at Monastir (Bitolia), in Romanian, although some literary creations were written in the Aromanian dialect, and subtitled Revista populară a românilor din Imperiul Otoman (“The People’s Magazine for Romanians in the Ottoman Empire”) and Revista poporană a românilor din dreapta Dunărei [“The People’s Magazine of the Romanians on the Right Side of the Danube”]; Grai bun [“Good Language”]. Bucharest, 1906-1907, subtitled Revistă aromânească [Aromanian Magazine]; Viaţa albano-română [“The Albano-Romaninan Life”]. Bucharest: 1909-1910; Lilicea Pindului [“The Pindus’s Flower”].