Appendices 151-158 Appendix 1.Qxd 6/21/05 4:31 PM Page 138

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Bradford Institutional Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Where available access to the published online version may require a subscription. Author(s): Gibson, Alex M. Title: An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Publication year: 2012 Book title: Enclosing the Neolithic : Recent studies in Britain and Ireland. Report No: BAR International Series 2440. Publisher: Archaeopress. Link to publisher’s site: http://www.archaeopress.com/archaeopressshop/public/defaultAll.asp?QuickSear ch=2440 Citation: Gibson, A. (2012). An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? In: Gibson, A. (ed.). Enclosing the Neolithic: Recent studies in Britain and Europe. Oxford: Archaeopress. BAR International Series 2440, pp. 1-20. Copyright statement: © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2012. An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Alex Gibson Abstract This paper summarises 80 years of ‘henge’ studies. It considers the range of monuments originally considered henges and how more diverse sites became added to the original list. It examines the diversity of monuments considered to be henges, their origins, their associated monument types and their dates. Since the introduction of the term, archaeologists have often been uncomfortable with it. -

Concrete Prehistories: the Making of Megalithic Modernism 1901-1939

Concrete Prehistories: The Making of Megalithic Modernism Abstract After water, concrete is the most consumed substance on earth. Every year enough cement is produced to manufacture around six billion cubic metres of concrete1. This paper investigates how concrete has been built into the construction of modern prehistories. We present an archaeology of concrete in the prehistoric landscapes of Stonehenge and Avebury, where concrete is a major component of megalithic sites restored between 1901 and 1964. We explore how concreting changed between 1901 and the Second World War, and the implications of this for constructions of prehistory. We discuss the role of concrete in debates surrounding restoration, analyze the semiotics of concrete equivalents for the megaliths, and investigate the significance of concreting to interpretations of prehistoric building. A technology that mixes ancient and modern, concrete helped build the modern archaeological imagination. Concrete is the substance of the modern –”Talking about concrete means talking about modernity” (Forty 2012:14). It is the material most closely associated with the origins and development of modern architecture, but in the modern era, concrete has also been widely deployed in the preservation and display of heritage. In fact its ubiquity means that concrete can justifiably claim to be the single most dominant substance of heritage conservation practice between 1900 and 1945. This paper investigates how concrete has been built into the construction of modern pasts, and in particular, modern prehistories. As the pre-eminent marker of modernity, concrete was used to separate ancient from modern, but efforts to preserve and display prehistoric megaliths saw concrete and megaliths become entangled. -

Cuisine and Consumption at the Late Neolithic Site of Durrington Walls

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery Feeding Stonehenge: cuisine and consumption at the Late Neolithic site of Durrington Walls Oliver E. Craiga, Lisa-Marie Shillitoa,b, Umberto Albarellac, Sarah Viner-Danielsc, Ben Chanc,d, Ros Cleale, Robert Ixerf, Mandy Jayg, Pete Marshallh., Ellen Simmonsc, Elizabeth Wrightc and Mike Parker Pearsonf aBioArCh, Department of Archaeology, University of York, Heslington, York YO10 5DD, UK. b School of History, Classics and Archaeology, University of Edinburgh, UK cDepartment of Archaeology, University of Sheffield, UK d Laboratory for Artefact Studies, Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden University, The Netherlands e Alexander Keiller Museum, Avebury, Wiltshire, UK f Institute of Archaeology, University College London, London, UK g Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Department of Human Evolution, Deutscher Platz 6, 04103 Leipzig, Germany h English Heritage, 1 Waterhouse Square, 138-142 Holborn, London, UK Introduction Henges are distinctive monuments of the Late Neolithic in Britain, defined as ditched enclosures in which a bank is constructed outside the ditch. The largest is Durrington Walls (Fig 1), a 17ha monument near Stonehenge. Excavations at Durringon Walls from 1966 to 1968 revealed the remains of two timber circles, the Northern and Southern Circles, within the henge enclosure (Wainwright and Longworth, 1971). More recent excavations (2004-2007) have identified a settlement that pre-dates the henge by a few decades and is concurrent with the main construction phase of Stonehenge (Parker Pearson et al., 2007, Parker Pearson, 2007, Thomas, 2007). Middens and pits, with substantial quantities of animal bones, broken Grooved Ware ceramics and other food-related debris, accumulated quickly since the settlement has an estimated start of 2535-2475 cal BC (95% probability) and a use of 0-55 years (95% probability). -

Stonehenge WHS Committee Minutes September 2015

Stonehenge World Heritage Site Committee Meeting on Thursday 24 September 2015 at St Barbara’s Hall, Larkhill Minutes 1. Introductions and apologies Present: Roger Fisher (Chair/Amesbury TC), Colin Shell (ASAHRG), Philip Miles (CLA), Kate Davies (English Heritage), Phil McMahon (Historic England), Rachel Sandy (Highways England), Richard Crook (NFU/Amesbury TC), Jan Tomlin (National Trust), Nick Snashall (National Trust), Patrick Cashman (RSPB), Carole Slater (Shrewton PC), Clare King (Wiltshire Council), David Dawson (Wiltshire Museum), Ian West (Winterbourne Stoke PC) Apologies: Fred Westmoreland (Amesbury Community Area Board), John Mills (Durrington TC), Henry Owen John (Historic England), Stephanie Payne (Natural England), David Andrews (VisitWiltshire), Peter Bailey (Wilsford cum Lake/WHS landowners), Melanie Pomeroy‐Kellinger (Wiltshire Council), Ariane Crampton (Wiltshire Council), Andrew Shuttleworth (Winterbourne Stoke PC), Alistair Sommerlad (WHS Partnership Panel) 2.0 Agree minutes of last meeting & matters arising Version 3 of the minutes of the last meeting was approved. 3.0 Stonehenge and Avebury WHS Management Plan Endorsing the Plan The following organisations have endorsed the plan so far: Highways England, English Heritage, Amesbury PC, Wilsford cum Lake PC, Durrington TC, Wiltshire Museum, and Salisbury Museum. Other organisations: Natural England, RSPB, Historic England and National Trust are in the process of going through their organisation’s approval process. The WHS Coordination Unit (WHSCU) would be grateful for written endorsements by the end of 2015. The WHSCU are very happy to meet with any partner organisation to explain the Management Plan to their members. WHSCU Action Plan BT circulated a table which outlined how SS and BT will cover both local and thematic responsibilities. -

Stonehenge Bibliography

Bibliography Abbot, M. and Anderson-Whymark, H., 2012. Anon., 2011a, Discoveries provide evidence of Stonehenge Laser Scan: archaeological celestial procession at Stonehenge. On-line analysis report. English Heritage project source available at: 6457. English Heritage Research Report http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/news/latest/ Series no. 32-2012, available at: 2011/11/25Nov-Discoveries-provide- http://services.english- evidence-of-a-celestial-procession-at- herita ge.org.uk/Resea rch Repo rtsPdf s/032_ Stonehenge.aspx (accessed 2 April 2012). 2012WEB.pdf Anon., 2011b, Stonehenge’s sister? Current Alexander, C., 2009, If the stones could speak: Archaeology, 260, 6–7. Searching for the meaning of Stonehenge. Anon., 2011c, Home is where the heath is. National Geographic, 213.6 (June 2008), Late Neolithic house, Durrington Walls. 34–59. Current Archaeology, 256, 42–3. Allen, S., 2008, The quest for the earliest Anon., 2011d, Stonehenge rocks. Current published image of Stonehinge (sic). Archaeology, 254, 6–7. Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural Anon., 2012a, Origin of some of the Bluestone History Magazine, 101, 257–9. debris at Stonehenge. British Archaeology, Anon., 2006, Excavation and Fieldwork in 123, 9. Wiltshire 2004. Wiltshire Archaeological Anon., 2012b, Stonehenge: sourcing the and Natural History Magazine, 99, 264–70. Bluestones. Current Archaeology, 263, 6– Anon., 2007a, Excavation and Fieldwork in 7. Wiltshire 2005. Wiltshire Archaeological Aronson, M., 2010, If stones could speak. and Natural History Magazine, 100, 232– Unlocking the secrets of Stonehenge. 39. Washington DC: National Geographic. Anon., 2007b, Before Stonehenge: village of Avebury Archaeological and Historical wild parties. Current Archaeology, 208, Research Group (AAHRG) 2001 17–21. -

WILTSHIRE Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph WILTSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. Parish Location Position WI_AMAV00 SU 15217 41389 UC road AMESBURY Church Street; opp. No. 41 built into & flush with churchyard wall Stonehenge Road; 15m W offield entrance 70m E jcn WI_AMAV01 SU 13865 41907 UC road AMESBURY A303 by the road WI_AMHE02 SU 12300 42270 A344 AMESBURY Stonehenge Down, due N of monument on the Verge Winterbourne Stoke Down; 60m W of edge Fargo WI_AMHE03 SU 10749 42754 A344 WINTERBOURNE STOKE Plantation on the Verge WI_AMHE05 SU 07967 43180 A344 SHREWTON Rollestone top of hill on narrow Verge WI_AMHE06 SU 06807 43883 A360 SHREWTON Maddington Street, Shrewton by Blind House against wall on Verge WI_AMHE09 SU 02119 43409 B390 CHITTERNE Chitterne Down opp. tank crossing next to tree on Verge WI_AMHE12 ST 97754 43369 B390 CODFORD Codford Down; 100m W of farm track on the Verge WI_AMHE13 ST 96143 43128 B390 UPTON LOVELL Ansty Hill top of hill,100m E of line of trees on Verge WI_AMHE14 ST 94519 42782 B390 KNOOK Knook Camp; 350m E of entrance W Farm Barns on bend on embankment WI_AMWH02 SU 12272 41969 A303 AMESBURY Stonehenge Down, due S of monument on the Verge WI_AMWH03 SU 10685 41600 A303 WILSFORD CUM LAKE Wilsford Down; 750m E of roundabout 40m W of lay-by on the Verge in front of ditch WI_AMWH05 SU 07482 41028 A303 WINTERBOURNE STOKE Winterbourne Stoke; 70m W jcn B3083 on deep verge WI_AMWH11 ST 990 364 A303 STOCKTON roadside by the road WI_AMWH12 ST 975 356 A303 STOCKTON 400m E of parish boundary with Chilmark by the road WI_AMWH18 ST 8759 3382 A303 EAST KNOYLE 500m E of Willoughby Hedge by the road WI_BADZ08 ST 84885 64890 UC road ATWORTH Cock Road Plantation, Atworth; 225m W farm buildings on the Verge WI_BADZ09 ST 86354 64587 UC road ATWORTH New House Farm; 25m W farmhouse on the Verge Registered Charity No 1105688 1 Entries in red - require a photograph WILTSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. -

Stonehenge OCR Spec B: History Around Us

OCR HISTORY AROUND US Site Proposal Form Example from English Heritage The Criteria The study of the selected site must focus on the relationship between the site, other historical sources and the aspects listed in a) to n) below. It is therefore essential that centres choose a site that allows learners to use its physical features, together with other historical sources as appropriate, to understand all of the following: a) The reasons for the location of the site within its surroundings b) When and why people first created the site c) The ways in which the site has changed over time d) How the site has been used throughout its history e) The diversity of activities and people associated with the site f) The reasons for changes to the site and to the way it was used g) Significant times in the site’s past: peak activity, major developments, turning points h) The significance of specific features in the physical remains at the site i) The importance of the whole site either locally or nationally, as appropriate j) The typicality of the site based on a comparison with other similar sites k) What the site reveals about everyday life, attitudes and values in particular periods of history l) How the physical remains may prompt questions about the past and how historians frame these as valid historical enquiries m) How the physical remains can inform artistic reconstructions and other interpretations of the site n) The challenges and benefits of studying the historic environment 1 Copyright © OCR 2018 Site name: STONEHENGE Created by: ENGLISH HERITAGE LEARNING TEAM Please provide an explanation of how your site meets each of the following points and include the most appropriate visual images of your site. -

Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present

Parker Pearson, M 2013 Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present. Archaeology International, No. 16 (2012-2013): 72-83, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/ai.1601 ARTICLE Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present Mike Parker Pearson* Over the years archaeologists connected with the Institute of Archaeology and UCL have made substantial contributions to the study of Stonehenge, the most enigmatic of all the prehistoric stone circles in Britain. Two of the early researchers were Petrie and Childe. More recently, colleagues in UCL’s Anthropology department – Barbara Bender and Chris Tilley – have also studied and written about the monument in its landscape. Mike Parker Pearson, who joined the Institute in 2012, has been leading a 10-year-long research programme on Stonehenge and, in this paper, he outlines the history and cur- rent state of research. Petrie and Childe on Stonehenge William Flinders Petrie (Fig. 1) worked on Stonehenge between 1874 and 1880, publishing the first accurate plan of the famous stones as a young man yet to start his career in Egypt. His numbering system of the monument’s many sarsens and blue- stones is still used to this day, and his slim book, Stonehenge: Plans, Descriptions, and Theories, sets out theories and observations that were innovative and insightful. Denied the opportunity of excavating Stonehenge, Petrie had relatively little to go on in terms of excavated evidence – the previous dig- gings had yielded few prehistoric finds other than antler picks – but he suggested that four theories could be considered indi- vidually or in combination for explaining Stonehenge’s purpose: sepulchral, religious, astronomical and monumental. -

Wilsford Cum Lake - Census 1911

Wilsford cum Lake - Census 1911 Page Year Years Total No Children Address Surname Given Names Relationship Status Age Sex Occupation Industry or Service Employment Status Place of Birth Nationality if not British Infirmity Notes Number Born Married Children Living Died 1 Normanton Farm Crook Isaac Charles Head Unmarried 31 M 1880 Farmer Fyfield, Hampshire 1 Normanton Farm Crook Caroline Louise Sister Unmarried 38 F 1873 House Keeper Gomeldon, Wiltshire 1 Normanton Farm Merritt Flora Eliza Lucy Servant Unmarried 14 F 1897 General Domestic Servant Netton, Wiltshire 2 Normanton Ford Henry George Head Married 52 M 1859 29 Labourer on Farm Teffont Magna, Wiltshire 2 Normanton Ford Elizabeth Wife Married 48 F 1863 29 Stratford sub Castle, Wiltshire 2 Normanton Ford Charles Son 23 M 1888 Groom on Farm Stockton, Wiltshire 2 Normanton Ford George Son 8 M 1903 Winterbourne Stoke, Wiltshire 3 Normanton Cottage, Normanton Case Thomas Head Married 42 M 1869 18 Cowman on Fram Cann, Shaftesbury, Dorset 3 Normanton Cottage, Normanton Case Louisa Wife Married 46 F 1865 18 Charlton All Saints, Wiltshire 3 Normanton Cottage, Normanton Case Thomas Son 15 M 1896 Cowlad on Farm Netherhampton, Wiltshire 4 Reegers Cottage, Normanton Wilkins Walter Head Married 28 M 1883 4 River Reyer Woodford, Wiltshire 4 Reegers Cottage, Normanton Wilkins Mary Jane Wife Married 33 F 1878 4 Norbiton, Surrey 5 Normanton Arnold Edward Head Married 26 M 1885 2 Groom and Gardener on Farm Mere, Wiltshire 5 Normanton Arnold Louisa Wife Married 23 F 1888 2 Shroton, Dorset 5 Normanton -

A303 Stonehenge PEIR Figures and Appendices Part 4

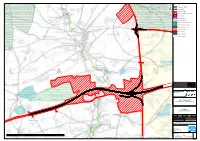

NOTES / LEGEND Proposed Carriageway ± Proposed Tunnel Public Right of Way Proposed draft DCO site boundary 1km Study Area Noise Important Area Scheduled Monument Special Site of Scientific Interest Special Area of Conservation Special Protection Area Community Facility Place of Worship Residential Building World Heritage Site River Till © Crown copyright and database rights 2017 Ordnance Survey 100030649. By Revision Details Date Suffix Check Purpose of issue FINAL Client Highways England 3528 Project Title 3527 A303 STONEHENGE AMESBURY TO BERWICK DOWN Drawing Title Winterbourne Stoke FIGURE 9.1 NOISE ASSESSMENT Designed Drawn Checked Approved Date HS GM/KD CC WB 13/12/17 Internal Project No. 60547200 Scale @ A3 Zone Berwick Down 1:25,000 SW THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN PREPARED PURSUANT TO AND SUBJECT TO THE TERMS OF AECOM'S APPOINTMENT BY ITS CLIENT. AECOM ACCEPTS NO LIABILITY FOR ANY USE OF THIS DOCUMENT OTHER THAN BY ITS ORIGINAL CLIENT OR FOLLOWING AECOM'S EXPRESS AGREEMENT TO SUCH USE, AND ONLY FOR THE PURPOSES FOR WHICH IT WAS PREPARED AND PROVIDED. Highways England Temple Quay House 2 The Square, Temple Quay Bristol BS1 6HA Drawing Number Rev Highways England PIN | Originator | Volume HE551506 AMW GEN 01 0.5 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 km Filename: pw:\\UKLON3AP114.aecomonline.local:PWAECOM_EU\Documents\60541439-A303 Stonehenge Technical Partner\0300 Non Deliverables\0330 Environmental Management Team\GIS\HE551506-AMW-DR-GI-00087.mxd SCHEME WIDE GN GI 00087 Location | Type | Role | Number NOTES / LEGEND Proposed Carriageway ± Proposed Tunnel Public Right of Way Proposed draft DCO site boundary 1km Study Area Noise Important Area Scheduled Monument Special Site of Scientific Interest Special Area of Conservation Special Protection Area Community Facility Educational Building Medical Building Place of Worship Residential Building River Avon World Heritage Site 12683 12682 © Crown copyright and database rights 2017 Ordnance Survey 100030649. -

Ever Increasing Circles: the Sacred Geographies of Stonehenge and Its Landscape

Proceedings of the British Academy, 92, 167-202 Ever Increasing Circles: The Sacred Geographies of Stonehenge and its Landscape TIMOTHY DARVILL Introduction THE GREAT STONE CIRCLE standing on the rolling chalk downland of Salisbury Plain that we know today as Stonehenge, has, in the twentieth century AD, become a potent icon for the ancient world, and the focus of power struggles and contested authority in our own. Its reputation and stature as an archaeological monument are enormous, and sometimes almost threaten to overshadow both its physical proportions and our accumu- lated collective understanding of its construction and use. While considerable attention has recently been directed to the relevance, meaning and use of the site in the twentieth century AD (Chippindale 1983; 1986a; Chippindale et al. 1990; Bender 1992), the matter of its purpose, significance, and operation during Neolithic and Bronze Age times remains obscure. The late Professor Richard Atkinson was characteristically straightforward when he said that for questions about Stonehenge which begin with the word ‘why’: ‘there is one short, simple and perfectly correct answer: We do not know’ (1979, 168). Two of the most widely recognised and enduring interpretations of Stonehenge are, first, that it was a temple of some kind; and, second, that its orientation on the midsummer sunrise gave it some sort of astronomical role in the lives of its builders. Both interpre- tations, which are not mutually exclusive, have of course been taken to absurd lengths on occasion. During the eighteenth century, for example, William Stukeley became obses- sive about the role of the Druids at Stonehenge (Stukeley 1740). -

Circular Route from Durrington Walls to Stonehenge

Circular route from Durrington Walls 3 Stonehenge Cottages, King to Stonehenge Barrows, Amesbury, Wiltshire SP4 7DD This walk explores two major historic monuments, Durrington TRAIL Walls and Stonehenge, in Walking the heart of the Stonehenge World Heritage Site. On this GRADE circular walk you will discover the Moderate landscape in its full glory from the Bronze Age barrows to the First DISTANCE World War military railway track, 5 miles (7.6km) as well as its diverse wildlife and plants. TIME 4 hours Terrain OS MAP Landranger 184; This circular walk follows hard tracks and gently sloping downs. Surfaces can be uneven, with potholes Explorer 130 or long tussocky grass. Dogs welcome on a lead and under control, as sheep and cattle graze the fields and there are ground-nesting birds. Contact Things to see 01980 664780 [email protected] Facilities Durrington Walls The old railway track The Avenue Have a look around you and Stonehenge Landscape has a This impressive bank and ditch http://nationaltrust.org.uk/walks appreciate the nature of this rich military history. The Lark Hill earthwork is more than 1.5 henge as an enclosed valley. Military Light Railway (LMLR) miles (2.5km) long. It may have If you were here over 4,500 line, ran through the landscape been the ceremonial route and years ago you would have seen from Amesbury to Larkhill and on entrance to the stone circle and In partnership with several shrines around the to the Stonehenge aerodrome recent excavations suggest it slopes, and Neolithic houses from 1914 until 1929.