Stonehenge Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concrete Prehistories: the Making of Megalithic Modernism 1901-1939

Concrete Prehistories: The Making of Megalithic Modernism Abstract After water, concrete is the most consumed substance on earth. Every year enough cement is produced to manufacture around six billion cubic metres of concrete1. This paper investigates how concrete has been built into the construction of modern prehistories. We present an archaeology of concrete in the prehistoric landscapes of Stonehenge and Avebury, where concrete is a major component of megalithic sites restored between 1901 and 1964. We explore how concreting changed between 1901 and the Second World War, and the implications of this for constructions of prehistory. We discuss the role of concrete in debates surrounding restoration, analyze the semiotics of concrete equivalents for the megaliths, and investigate the significance of concreting to interpretations of prehistoric building. A technology that mixes ancient and modern, concrete helped build the modern archaeological imagination. Concrete is the substance of the modern –”Talking about concrete means talking about modernity” (Forty 2012:14). It is the material most closely associated with the origins and development of modern architecture, but in the modern era, concrete has also been widely deployed in the preservation and display of heritage. In fact its ubiquity means that concrete can justifiably claim to be the single most dominant substance of heritage conservation practice between 1900 and 1945. This paper investigates how concrete has been built into the construction of modern pasts, and in particular, modern prehistories. As the pre-eminent marker of modernity, concrete was used to separate ancient from modern, but efforts to preserve and display prehistoric megaliths saw concrete and megaliths become entangled. -

WILTSHIRE Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph WILTSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. Parish Location Position WI_AMAV00 SU 15217 41389 UC road AMESBURY Church Street; opp. No. 41 built into & flush with churchyard wall Stonehenge Road; 15m W offield entrance 70m E jcn WI_AMAV01 SU 13865 41907 UC road AMESBURY A303 by the road WI_AMHE02 SU 12300 42270 A344 AMESBURY Stonehenge Down, due N of monument on the Verge Winterbourne Stoke Down; 60m W of edge Fargo WI_AMHE03 SU 10749 42754 A344 WINTERBOURNE STOKE Plantation on the Verge WI_AMHE05 SU 07967 43180 A344 SHREWTON Rollestone top of hill on narrow Verge WI_AMHE06 SU 06807 43883 A360 SHREWTON Maddington Street, Shrewton by Blind House against wall on Verge WI_AMHE09 SU 02119 43409 B390 CHITTERNE Chitterne Down opp. tank crossing next to tree on Verge WI_AMHE12 ST 97754 43369 B390 CODFORD Codford Down; 100m W of farm track on the Verge WI_AMHE13 ST 96143 43128 B390 UPTON LOVELL Ansty Hill top of hill,100m E of line of trees on Verge WI_AMHE14 ST 94519 42782 B390 KNOOK Knook Camp; 350m E of entrance W Farm Barns on bend on embankment WI_AMWH02 SU 12272 41969 A303 AMESBURY Stonehenge Down, due S of monument on the Verge WI_AMWH03 SU 10685 41600 A303 WILSFORD CUM LAKE Wilsford Down; 750m E of roundabout 40m W of lay-by on the Verge in front of ditch WI_AMWH05 SU 07482 41028 A303 WINTERBOURNE STOKE Winterbourne Stoke; 70m W jcn B3083 on deep verge WI_AMWH11 ST 990 364 A303 STOCKTON roadside by the road WI_AMWH12 ST 975 356 A303 STOCKTON 400m E of parish boundary with Chilmark by the road WI_AMWH18 ST 8759 3382 A303 EAST KNOYLE 500m E of Willoughby Hedge by the road WI_BADZ08 ST 84885 64890 UC road ATWORTH Cock Road Plantation, Atworth; 225m W farm buildings on the Verge WI_BADZ09 ST 86354 64587 UC road ATWORTH New House Farm; 25m W farmhouse on the Verge Registered Charity No 1105688 1 Entries in red - require a photograph WILTSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. -

Stonehenge and Avebury WHS Management Plan 2015 Summary

Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 1 Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site Vision The Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site is universally important for its unique and dense concentration of outstanding prehistoric monuments and sites which together form a landscape without parallel. We will work together to care for and safeguard this special area and provide a tranquil, rural and ecologically diverse setting for it and its archaeology. This will allow present and future generations to explore and enjoy the monuments and their landscape setting more fully. We will also ensure that the special qualities of the World Heritage Site are presented, interpreted and enhanced where appropriate, so that visitors, the local community and the whole world can better understand and value the extraordinary achievements © K020791 Historic England © K020791 Historic of the prehistoric people who left us this rich legacy. Avebury Stone Circle We will realise the cultural, scientific and educational potential of the World Heritage Site as well as its social and economic benefits for the community. © N060499 Historic England © N060499 Historic Stonehenge in summer 2 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 1 World Heritage Sites © K930754 Historic England © K930754 Historic Arable farming in the WHS below the Ridgeway, Avebury The Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site is internationally important for its complexes of outstanding prehistoric monuments. Stonehenge is the most architecturally sophisticated prehistoric stone circle in the world, while Avebury is Stonehenge and Avebury were inscribed as a single World Heritage Site in 1986 for their outstanding prehistoric monuments the largest. -

Stonehenge OCR Spec B: History Around Us

OCR HISTORY AROUND US Site Proposal Form Example from English Heritage The Criteria The study of the selected site must focus on the relationship between the site, other historical sources and the aspects listed in a) to n) below. It is therefore essential that centres choose a site that allows learners to use its physical features, together with other historical sources as appropriate, to understand all of the following: a) The reasons for the location of the site within its surroundings b) When and why people first created the site c) The ways in which the site has changed over time d) How the site has been used throughout its history e) The diversity of activities and people associated with the site f) The reasons for changes to the site and to the way it was used g) Significant times in the site’s past: peak activity, major developments, turning points h) The significance of specific features in the physical remains at the site i) The importance of the whole site either locally or nationally, as appropriate j) The typicality of the site based on a comparison with other similar sites k) What the site reveals about everyday life, attitudes and values in particular periods of history l) How the physical remains may prompt questions about the past and how historians frame these as valid historical enquiries m) How the physical remains can inform artistic reconstructions and other interpretations of the site n) The challenges and benefits of studying the historic environment 1 Copyright © OCR 2018 Site name: STONEHENGE Created by: ENGLISH HERITAGE LEARNING TEAM Please provide an explanation of how your site meets each of the following points and include the most appropriate visual images of your site. -

World Heritage 32 COM

World Heritage 32 COM Distribution Limited WHC-08/32.COM/8B.Add Paris, 25 June 2008 Original: English/French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Thirty second Session Quebec City, Canada 2 – 10 July 2008 Item 8B of the Provisional Agenda: Nominations to the World Heritage List Nominations to the World Heritage List SUMMARY This Addendum presents the Draft Decisions concerning 5 nominations of properties deferred or referred back by previous sessions of the World Heritage Committee, 21 minor modifications to the boundaries and 29 revisions of Statements of Significance or Statements of Outstanding Universal Value of already inscribed properties and 1 change of criteria to be examined by the World Heritage Committee at its 32nd session in 2008. Decision required: The Committee is requested to examine the Draft Decisions presented in this Addendum and take its Decisions in accordance with paragraphs 153, 155, 163 and 164 of the Operational Guidelines. I. Changes to criteria of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List The World Heritage Committee at its 30th session (Vilnius, 2006) approved 17 changes of criteria numbering for Natural and Mixed properties inscribed for geological values before 1994 (Document WHC- 06/30.COM/8D). For only two properties (see table below), in the group of properties that was inscribed under natural criteria (ii) before 1994, was no change in criteria numbering requested at that time, as the State Party asked for further time to consult the stakeholders concerned. Following consultations with the stakeholders and IUCN, it was agreed that the criteria should be as shown in the table here below. -

Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present

Parker Pearson, M 2013 Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present. Archaeology International, No. 16 (2012-2013): 72-83, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/ai.1601 ARTICLE Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present Mike Parker Pearson* Over the years archaeologists connected with the Institute of Archaeology and UCL have made substantial contributions to the study of Stonehenge, the most enigmatic of all the prehistoric stone circles in Britain. Two of the early researchers were Petrie and Childe. More recently, colleagues in UCL’s Anthropology department – Barbara Bender and Chris Tilley – have also studied and written about the monument in its landscape. Mike Parker Pearson, who joined the Institute in 2012, has been leading a 10-year-long research programme on Stonehenge and, in this paper, he outlines the history and cur- rent state of research. Petrie and Childe on Stonehenge William Flinders Petrie (Fig. 1) worked on Stonehenge between 1874 and 1880, publishing the first accurate plan of the famous stones as a young man yet to start his career in Egypt. His numbering system of the monument’s many sarsens and blue- stones is still used to this day, and his slim book, Stonehenge: Plans, Descriptions, and Theories, sets out theories and observations that were innovative and insightful. Denied the opportunity of excavating Stonehenge, Petrie had relatively little to go on in terms of excavated evidence – the previous dig- gings had yielded few prehistoric finds other than antler picks – but he suggested that four theories could be considered indi- vidually or in combination for explaining Stonehenge’s purpose: sepulchral, religious, astronomical and monumental. -

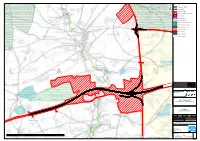

A303 Stonehenge PEIR Figures and Appendices Part 4

NOTES / LEGEND Proposed Carriageway ± Proposed Tunnel Public Right of Way Proposed draft DCO site boundary 1km Study Area Noise Important Area Scheduled Monument Special Site of Scientific Interest Special Area of Conservation Special Protection Area Community Facility Place of Worship Residential Building World Heritage Site River Till © Crown copyright and database rights 2017 Ordnance Survey 100030649. By Revision Details Date Suffix Check Purpose of issue FINAL Client Highways England 3528 Project Title 3527 A303 STONEHENGE AMESBURY TO BERWICK DOWN Drawing Title Winterbourne Stoke FIGURE 9.1 NOISE ASSESSMENT Designed Drawn Checked Approved Date HS GM/KD CC WB 13/12/17 Internal Project No. 60547200 Scale @ A3 Zone Berwick Down 1:25,000 SW THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN PREPARED PURSUANT TO AND SUBJECT TO THE TERMS OF AECOM'S APPOINTMENT BY ITS CLIENT. AECOM ACCEPTS NO LIABILITY FOR ANY USE OF THIS DOCUMENT OTHER THAN BY ITS ORIGINAL CLIENT OR FOLLOWING AECOM'S EXPRESS AGREEMENT TO SUCH USE, AND ONLY FOR THE PURPOSES FOR WHICH IT WAS PREPARED AND PROVIDED. Highways England Temple Quay House 2 The Square, Temple Quay Bristol BS1 6HA Drawing Number Rev Highways England PIN | Originator | Volume HE551506 AMW GEN 01 0.5 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 km Filename: pw:\\UKLON3AP114.aecomonline.local:PWAECOM_EU\Documents\60541439-A303 Stonehenge Technical Partner\0300 Non Deliverables\0330 Environmental Management Team\GIS\HE551506-AMW-DR-GI-00087.mxd SCHEME WIDE GN GI 00087 Location | Type | Role | Number NOTES / LEGEND Proposed Carriageway ± Proposed Tunnel Public Right of Way Proposed draft DCO site boundary 1km Study Area Noise Important Area Scheduled Monument Special Site of Scientific Interest Special Area of Conservation Special Protection Area Community Facility Educational Building Medical Building Place of Worship Residential Building River Avon World Heritage Site 12683 12682 © Crown copyright and database rights 2017 Ordnance Survey 100030649. -

Preliminary Outline Assessment of the Impact of A303 Improvements On

Preliminary Outline Assessment of the impact of A303 improvements on the Outstanding Universal Value of the Stonehenge Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage property Nicola Snashall BA MA PhD MIfA National Trust Christopher Young BA MA DPhil FSA Christopher Young Heritage Consultancy August 2014 ©English Heritage and The National Trust Preliminary Outline Impact Assessment of A303 improvements on the Outstanding Universal Value of the Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage property August 2014 Executive Summary The Government have asked the Highways Agency to prepare feasibility studies for the improvement of six strategic highways in the UK. One of these is the A303 including the single carriageway passing Stonehenge. This study has been commissioned by English Heritage and the National Trust to make an outline preliminary assessment of the potential impact of such road improvements on the Outstanding Universal Value of the World Heritage property. A full impact assessment, compliant with the ICOMOS guidance and with EU and UK regulations for Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) would be a much larger task than this preliminary assessment. It would be prepared by the promoter of a road scheme and would require more supporting material and more detailed analysis of impacts. The present study is an outline preliminary assessment intended to inform the advice provided by the National Trust and English Heritage to the Highways Agency and the Department for Transport. It deals only with impact on Outstanding Universal Value and does not examine impacts on nationally or locally significant heritage. The objectives of the study can be summarised as: 1. Review changes in international and national policy and in our understanding of the Outstanding Universal Value of the World Heritage property to set the context for the assessment of impact of potential options for improvement of the A303; 2. -

Pearson, M. P. & Al.: Stonehenge for the Ancestors, 1

PEARSON, M. P. & AL.: STONEHENGE FOR THE ANCESTORS, 1: LANDSCAPE AND MONUMENTS 1. Introduction The Stonehenge Riverside Project Background to the project Implications of the hypothesis Research aims M. Parker Pearson, J. Pollard, C. Richards, J. Thomas C. Tilley, K. Welham and P. Marshall 2. Fourth millennium BC beginnings: monuments in the landscape The landscape of the fourth millennium BC – (C. Tilley, W. Bennett and D. Field) Geophysical surveys of the Greater Cursus and Amesbury 42 long barrow – (K. Welham, C. Steele, L. Martin and A. Payne) 3. Fourth millennium BC beginnings: excavations of the Greater Cursus, Amesbury 42 long barrow and a tree-throw pit at Woodhenge The Greater Stonehenge Cursus – (J. Thomas) Amesbury 42 long barrow – (J. Thomas) Investigations of the buried soil beneath the mound of Amesbury 42 – (M.J. Allen) Stonehenge Lesser Cursus, Stonehenge Greater Cursus and the Amesbury 42 long barrow: radiocarbon dating – (P. D. Marshall, C. Bronk Ramsey and G. Cook) Antler artefact from the Greater Cursus and Amesbury 42 long barrow – (G. Davies) Pottery from the Greater Cursus and Amesbury 42 long barrow – (R. Cleal) Chalk artefact from the Greater Cursus – (A. Teather) Lithics from stratified contexts of the Greater Cursus – (B. Chan) Lithics from the ploughsoil of the Greater Cursus – (D. Mitcham) Lithics from stratified contexts of Amesbury 42 long barrow – (B. Chan) Human remains from Amesbury 42 long barrow and the Greater Cursus – (A. Chamberlain and C. Willis) Charred plant remains and wood charcoal from the Greater Cursus and Amesbury 42 long barrow – (E. Simmons) Woodhenge tree-throw pit – (J. Pollard) Pottery from the Woodhenge tree-throw pit – (Rosamund M.J. -

A303 Amesbury to Berwick Down

A303 Amesbury to Berwick Down TR010025 6.3 Environmental Statement Appendices Volume 1 6 Appendix 6.1 Annex 8 Influences of the monuments and landscape of the Stonehenge part of the World Heritage Site on literature and popular culture APFP Regulation 5(2)(a) Planning Act 2008 Infrastructure Planning (Applications: Prescribed Forms and Procedure) Regulations 2009 October 2018 HIA Annex 8 – Influences of the monuments and landscape of the Stonehenge part of the WHS on literature and popular culture Introduction Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage Site List in 1986, one of the original list of seven sites in the UK to be put forward for inscription. The Statement of Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) was adopted in 2013. The Statement of OUV notes that ‘the monuments and landscape have had an unwavering influence on architects, artists, historians and archaeologists’ (UNESCO 2013). The 2015 Management Plan (Simmonds & Thomas 2015) identifies seven Attributes of OUV for the entirety of the WHS, of which the seventh is: ‘The influence of the remains of the Neolithic and Bronze Age funerary and ceremonial monuments and their landscape setting on architects, artists, historians, archaeologists and others.’ The landscape around Stonehenge, comprising natural and cultural elements, is not just a physical environment, but an abstraction that is perceived by the human observer. Such observers have included literary writers, poets and travel writers, who have used their sense of the place as they experienced it to inspire their creative writing. The unique strength of Stonehenge is that the monument is an instantly recognisable structure which resembles no other and onto which a range of fantasies can be projected (Hutton 2009, 45). -

Ever Increasing Circles: the Sacred Geographies of Stonehenge and Its Landscape

Proceedings of the British Academy, 92, 167-202 Ever Increasing Circles: The Sacred Geographies of Stonehenge and its Landscape TIMOTHY DARVILL Introduction THE GREAT STONE CIRCLE standing on the rolling chalk downland of Salisbury Plain that we know today as Stonehenge, has, in the twentieth century AD, become a potent icon for the ancient world, and the focus of power struggles and contested authority in our own. Its reputation and stature as an archaeological monument are enormous, and sometimes almost threaten to overshadow both its physical proportions and our accumu- lated collective understanding of its construction and use. While considerable attention has recently been directed to the relevance, meaning and use of the site in the twentieth century AD (Chippindale 1983; 1986a; Chippindale et al. 1990; Bender 1992), the matter of its purpose, significance, and operation during Neolithic and Bronze Age times remains obscure. The late Professor Richard Atkinson was characteristically straightforward when he said that for questions about Stonehenge which begin with the word ‘why’: ‘there is one short, simple and perfectly correct answer: We do not know’ (1979, 168). Two of the most widely recognised and enduring interpretations of Stonehenge are, first, that it was a temple of some kind; and, second, that its orientation on the midsummer sunrise gave it some sort of astronomical role in the lives of its builders. Both interpre- tations, which are not mutually exclusive, have of course been taken to absurd lengths on occasion. During the eighteenth century, for example, William Stukeley became obses- sive about the role of the Druids at Stonehenge (Stukeley 1740). -

Stonehenge's Avenue and Bluestonehenge

Stonehenge’s Avenue and Bluestonehenge Michael J. Allen1, Ben Chan2, Ros Cleal3, Charles French4, Peter Marshall5, Joshua Pollard6, Rebecca Pullen7, Colin Richards8, Clive Ruggles9, David Robinson10, Jim Rylatt11, Julian Thomas8, Kate Welham12 & Mike Parker Pearson13,* Stonehenge has long been known to form part of a larger prehistoric landscape (Figure 1). In particular, it is part of a composite monument that includes the Stonehenge Avenue, first mapped in 1719–1723 by William Stukeley (1740) who recorded that it ran from Stonehenge’s northeast entrance for over a kilometre towards the River Avon, bending southeast and crossing King Barrow Ridge before disappearing under ploughed ground. He also noted that its initial 500m-long stretch from Stonehenge was aligned towards the midsummer solstice sunrise. Archaeological excavations during the 20th century revealed that the Avenue consists of two parallel banks with external, V-profile ditches, about 22m apart. The dating, phasing and extent of the Avenue, however, remained uncertain. Its length could be traced no closer than 200m from the River Avon (Smith 1973), and the question of whether the Avenue’s construction constituted a single event had not been entirely resolved (Cleal et al. 1995: 327). Our investigations were part of a re-evaluation of Stonehenge and its relationship to the River Avon in 2008–2009, involving the re-opening and extension of trenches previously dug across the Avenue during the 20th century and digging new trenches at West Amesbury beyond the then-known limit of the Avenue. The result of this work was the discovery of a new henge at West Amesbury, situated at the hitherto undiscovered east end of the Avenue beside the River Avon.