The Effect of School Closure On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dc Nº 360-2018.Pdf

. ,T, • ,-:;:/f; I/ .17' ?I' //1/{-11/..1/Ir• // 4/ (;;-,71/ ,./V /1://"Ve DECLARACIÓN CAMARAL N° 360/2018-2019 EL PLENO DE LA CÁMARA DE SENADORES, CONSIDERANDO: Que, la Provincia Aroma es una de las veinte provincias del Departamento de La Paz, limita al norte con las provincias Ingavi y Murillo, al este con la Provincia José Ramón Loayza, al sur con la Provincia Gualberto Villarroel y el Departamento de Oruro y al oeste con la Provincia Pacajes; cuenta con una superficie de 4.510 kilómetros y una población de 98.205 habitantes, según el Censo de Población y Vivienda del año 2012. La provincia está dividida en 7 municipios, su capital provincial es Sica Sica. La Provincia Aroma está compuesta por los municipios de Sica Sica, Umala, Ayo Ayo, Calamarca, Patacamaya, Colquencha y Collana. Que, la Provincia Aroma fue creada el 23 de noviembre de 1945, durante la presidencia de Gualberto Villarroel. La historia refiere que la apropiación de tierras comunitarias llevó al surgimiento de caudillos como Tupac Katari y Bartolina Sisa, en homenaje a ellos erigieron un monumento de granito en la plaza principal de Sica Sica, lugar en el que también descansan los restos de quienes protagonizaron la Batalla de Aroma, una de las batallas que permitió la independencia de Bolivia. Que, las principales actividades económicas en la Provincia Aroma, son la ganadería ovina y vacuna y la producción lechera; asimismo, su potencial agrícola se basa en el cultivo de la quinua y la cebada. Que, entre los atractivos turísticos de la Provincia Aroma, destacan el circuito de las iglesias coloniales, las ferias realizadas en cada sección y las aguas termales del balneario de Viscachani. -

Evaluación De Manejo De Suelos Productivos, Influenciados

UNIVERSIDAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRÉS FACULTAD DE AGRONOMÍA CARRERA DE INGENIERÍA EN PRODUCCIÓN Y COMERCIALIZACIÓN AGROPECUARIA TESIS DE GRADO EVALUACIÓN DE MANEJO DE SUELOS PRODUCTIVOS, INFLUENCIADOS POR LA PRESIÓN DEL MERCADO Y CAMBIO DEL CLIMA, EN COMUNIDADES DEL MUNICIPIO DE UMALA DEL DEPARTAMENTO DE LA PAZ PRESENTADO POR: Obispo Lara Villca La Paz – Bolivia 2016 UNIVERSIDAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRÉS FACULTAD DE AGRONOMÍA CARRERA DE INGENIERÍA DE PRODUCCIÓN Y COMERCIALIZACIÓN AGROPECUARIA EVALUACIÓN DE MANEJO DE SUELOS PRODUCTIVOS, INFLUENCIADOSPOR LA PRESIÓN DEL MERCADO Y CAMBIO DEL CLIMA, ENCOMUNIDADES DEL MUNICIPIO DE UMALA DEL DEPARTAMENTODE LA PAZ Tesis de Grado presentado como requisito Parcial para optar el título de Ingeniero en Producción y Comercialización Agropecuaria OBISPO LARA VILLCA Asesores: Ing. Ph.D. Roberto Miranda Casas …..…..…………………………… Ing. M.Sc. Edwin Eusebio Yucra Sea …………………………………… Comité Revisor: Ing. M.Sc. Brígido Moisés Quiroga Sossa ….......…………………………… Ing. Rolando Céspedes Paredes ….………….……………………. Ing. M.Sc. Rubén Jacobo Trigo Riveros ..…………………………………. Aprobada Presidente Tribunal Examinador: …………………………………… -2016- Dedicatoria: A mi amado Señor Jesucristo y a DIOS todo Poderoso que me da un día más de Vida. A mis papitos Teodoro Lara Delgado (†) y Gregoria Villca Choque (†) que ellos en vida me guiaron mi camino con mucho amor y fortaleza aquel día, por ellos estoy donde estoy y siempre les recordare, los quiero mucho. A mis queridos hermanos(as) por su comprensión, paciencia y apoyo incondicional. O. L. V. AGRADECIMIENTOS Mi sincero agradecimiento a Dios, por su infinito amor y misericordia, por haberse revelado a mi vida con fidelidad, puesto que fue mi alto refugio y fortaleza en todo momento, gracias por haberme bendecido con una familia y amigos(as) que llegué a conocer. -

Collana Conflicto Por La Tierra En El Altiplano 2 CONFLICTO POR LA TIERRA EN EL ALTIPLANO 3

1 Collana Conflicto por la tierra en el Altiplano 2 CONFLICTO POR LA TIERRA EN EL ALTIPLANO 3 Collana Conflicto por la tierra en el Altiplano 4 CONFLICTO POR LA TIERRA EN EL ALTIPLANO Esta publicación cuenta con el auspicio de: IDRC: Centro Internacional de Investigación y Desarrollo DFID: Departamento de Desarrollo Internacional ICCO: Organización Intereclesiástica para la Cooperación al Desarrollo EED: Servicio de las Iglesias Evangélicas de Alemania para el Desarrollo Editor: FUNDACIÓN TIERRA Calle Hermanos Manchego N° 2576 Telfs. (591 - 2) 243 0145 - 243 2263 La Paz-Bolivia. Cuidado de Edición: Daniela Otero Diseño de Tapa: Plural Editores Fotografía: José Luis Quintana © FUNDACIÓN TIERRA Primera edición, septiembre de 2003. ISBN: 99905-0-399-0 DL: 4-1-1251-03 Producción: Plural editores Rosendo Gutiérrez 595 esq. Ecuador Teléfono 2411018 / Casilla 5097, La Paz - Bolivia Email: [email protected] Impreso en Bolivia 5 Índice Presentación El conflicto por la tierra ...................................................................... 7 Primera parte Capítulo 1 Collana: la perla codiciada del Altiplano Daniela Otero ......................................................................................... 15 Capítulo 2 Tras las huellas de la historia Rossana Barragán y Florencia Durán .................................................... 27 Capítulo 3 El despojo en el marco de la ley Rossana Barragán y Florencia Durán .................................................... 37 Capítulo 4 Cuando el azar se mezcla con la política Daniela -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 14490-BO STAFF APPRAISAL REPORT BOLIVIA Public Disclosure Authorized RURAL WATER AND SANITATION PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized DECEMBER 15, 1995 Public Disclosure Authorized Country Department III Environment and Urban Development Division Latin America and the Caribbean Regional Office Currency Equivalents Currency unit = Boliviano US$1 = 4.74 Bolivianos (March 31, 1995) All figures in U.S. dollars unless otherwise noted Weights and Measures Metric Fiscal Year January 1 - December 31 Abbreviations and Acronyms DINASBA National Directorate of Water and Sanitation IDB International Development Bank NFRD National Fund for Regional Development NSUA National Secretariat for Urban Affairs OPEC Fund Fund of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries PROSABAR Project Management Unit within DINASBA UNASBA Departmental Water and Sanitation Unit SIF Social Investment Fund PPL Popular Participation Law UNDP United Nations Development Programme Bolivia Rural Water and Sanitation Project Staff Appraisal Report Credit and Project Summary .................................. iii I. Background .................................. I A. Socioeconomic setting .................................. 1 B. Legal and institutional framework .................................. 1 C. Rural water and sanitation ............................. , , , , , , . 3 D. Lessons learned ............................. 4 II. The Project ............................. 5 A. Objective ............................ -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Report No: ISR3102 Implementation Status & Results Bolivia Expanding Access to Reduce Health Inequities Project (APL III)--Former Health Sector Reform - Third Phase (APL III) (P101206) Operation Name: Expanding Access to Reduce Health Inequities Project (APL Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 10 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: III)--Former Health Sector Reform - Third Phase (APL III) (P101206) Public Disclosure Authorized Country: Bolivia Approval FY: 2008 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: LATIN AMERICA AND CARIBBEAN Lending Instrument: Adaptable Program Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Ministry of Health and Sports, Social Investment and Productive Fund (SPF) Public Disclosure Copy Key Dates Board Approval Date 24-Jan-2008 Original Closing Date 31-Jan-2014 Planned Mid Term Review Date 26-Mar-2012 Last Archived ISR Date 22-Feb-2011 Effectiveness Date 19-Jun-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Jan-2014 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The development objectives for APL III are the same as those of the previous two phases: increasing access to good quality and culturally appropriate health services to improve the health of the population in general and to mothers and children in particular. As a medium-term objective, the APL series pursues reducing the infant and maternal mortality rates by one-third, as per the proposed indicators for the Program. Public Disclosure Authorized Under APLs I and II an important set of policies and interventions were developed to strengthen the performance of the public health services. These policies and interventions aimed to improve child and maternal health status, including expansion of the insurance system (the Universal maternal and child insurance, SUMI, at present), the investments in primary health care, and the strengthening of cost-effective health interventions (PAI, IMCI). -

4.4 Charana Achiri Santiago De Llallagua Is. Taquiri General Gonzales 3.0 3.1 2.9

N ULLA ULLA TAYPI CUNUMA CAMSAYA CALAYA KAPNA OPINUAYA CURVA LAGUNILLA GRAL. J.J. PEREZ CHULLINA STA. ROSA DE CAATA CHARI GRAL. RAMON CARIJANA GONZALES 2.0 CAMATA AMARETEGENERAL GONZALES MAPIRI VILLA ROSARIO DE WILACALA PUSILLANI CONSATA MARIAPU INICUA BAJO MOCOMOCO AUCAPATA SARAMPIUNI TUILUNI AYATA HUMANATA PAJONAL CHUMA VILAQUE ITALAQUE SUAPI DE ALTO BENI SAN JUAN DE CANCANI LIQUISANI COLLABAMBA GUANAY COTAPAMPA TEOPONTE PUERTO ACOSTA CHINAÑA 6 SANTA ROSA DE AGOSTO ANANEA CARGUARANI PAUCARES CHAJLAYA BELEN SANTA ANA DEL TAJANI PTO. ESCOMA 130 PANIAGUA ALTO BENI PARAJACHI ANBANA TACACOMA YANI QUIABAYA TIPUANI COLLASUYO PALOS BLANCOS V. PUNI SANTA ROSA DE CHALLANA SAN MIGUEL CALLAPATA CALAMA EDUARDO AVAROA DE YARICOA TIMUSI OBISPO BOSQUE SOCOCONI VILLA ELEVACION PTO. CARABUCO CARRASCO LA RESERVA CHUCHULAYA ANKOMA SAPUCUNI ALTO ILLIMANI ROSARIO 112 SORATA CARRASCO ENTRE RIOS PTO. COMBAYA 115 CHAGUAYA ILABAYA ALCOCHE SAN PABLO SOREJAYA SANTA FE CHIÑAJA CARANAVI VILLA MACA MACA CHEJE MILLIPAYA ANCORAIMES SANTA ANA DE CARANAVI PAMPA UYUNENSE CAJIATA FRANZ TAMAYO PTO.RICO SOTALAYA TAYPIPLAYA WARISATA CHOJÑA COTAPATA SAN JUAN DE CHALLANA INCAHUARA DE CKULLO CUCHU ACHACACHI SAN JOSE V. SAN JUAN DE EL CHORO SANTIAGO AJLLATA V. ASUNCION DE CHACHACOMANI ZAMPAYA CORPAPUTO KALAQUE DE HUATA GRANDE CHARIA JANCKO AMAYA CHUA HUARINA MURURATA LA ASUNTA COPACABANA COCANI KERANI TITO YUPANKI CHUA SONCACHI CALATA VILASAYA HUATAJATA LOKHA DE S. M. SAN PABLO PEÑAS VILLA ASUNCION HUAYABAL DE T. COPANCARA TURGQUIA ZONGO KARHUISA COROICO CALISAYA CHAMACA V. AMACIRI2.9 PACOLLO SANTIAGO DE IS. TAQUIRI YANAMAYU SURIQUI HUANCANE OJJE PTO. ARAPATA COLOPAMPA GRANDE PEREZ VILLA BARRIENTOS LA CALZADA CASCACHI HUAYNA POTOSI LAS BATALLAS MERCEDES CORIPATA V. -

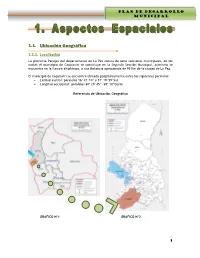

1.1. Ubicación Geográfica

PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL G.M. CAQUIAVIRI 1.1. Ubicación Geográfica 1.1.1. Localización La provincia Pacajes del departamento de La Paz consta de ocho secciones municipales, de los cuales el municipio de Caquiaviri se constituye en la Segunda Sección Municipal, asimismo se encuentra en la llanura altiplánica, a una distancia aproximada de 95 Km de la ciudad de La Paz. El municipio de Caquiaviri se encuentra ubicado geográficamente entre los siguientes paralelos: Latitud austral: paralelos 16º 47´10” y 17º 19´59”Sur Longitud occidental: paralelos 68º 29´45”- 69º 10”Oeste Referencia de Ubicación Geográfica GRAFICO Nº1 GRAFICO Nº2 1 PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL G.M. CAQUIAVIRI Ubicación del Municipio Caquiaviri en la Provincia Pacajes GRAFICO Nº3 1.1.2. Límites Territoriales El municipio de Caquiaviri tiene la siguiente delimitación: Límite Norte; Municipios de Jesús de Machaca y San Andrés de Machaca de la provincia Ingavi y el Municipio Nazacara de Pacajes que es la Séptima Sección de la provincia Pacajes del departamento de La Paz. Límite Sur; Municipios Coro Coro, Calacoto y Charaña que son Primera, Tercera y Quinta Sección de la provincia Pacajes del departamento de La Paz. Límite Este; Municipio Comanche que es Cuarta Sección de la provincia Pacajes del departamento de La Paz. Límite Oeste; Municipio de Santiago de Machaca de la provincia José Manuel Pando del departamento de La Paz. 1.1.3. Extensión La Provincia Pacajes posee una extensión total de 10.584 km², de la cual la Segunda Sección Municipal Caquiaviri representa el 14 % del total de la provincia, lo que equivale a una superficie de 1.478 Km². -

Departamento De La Paz

DEPARTAMENTO DE LA PAZ N E D L A R R U T I IXIAMAS LEGEND TUMUPASA Department Province SAN JOSE DE Capital of Canton CHUPUAMONAS RURRENABAQUE LEGEND SAN BUENA F R A N Z VENTURA T/L 230kV(Exist. 2000) T/L 115kV(Exist. 2000) PATA SAN MOJOS ANTONIO T/L 69kv(Exist. 2000) SANTA CRUZ DEL T/L 34.5kv(Exist. 2000) VALLE AMENO T A M A Y T/L 24.9kv(Exist. 2000) T/L 19.9kv(Exist. 2000) O T/L 14.4kv(Exist. 2000) APOLO PELECHUCO SUCHES PULI ANTAQUILA DE IMPLEMENTATION PLAN BY RENEWABLE ENERGY PLAN BY RENEWABLE IMPLEMENTATION COPACABANA ATEN JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY COOPERATION INTERNATIONAL JAPAN ULLA ULLA THE STUDY ON RURA TAYPI CUNUMA CAMSAYA CALAYA KAPNA OPINUAYA CURVA LAGUNILLASAAVEDRA GRAL. J.J. PEREZ CHULLINA STA. ROSA DE CAATA CHARI GRAL. RAMON CARIJANA IN THE REPUBLIC OF BOLIVIA GONZALES CAMATA YUCUMO AMARETE MAPIRI VILLA ROSARIO CAMAC DE WILACALA PUSILLANI CONSATA MARIAPU INICUA BAJO MOCOMOCO AUCAPATA SARAMPIUNI TUILUNI AYATA HUMANATA PAJONAL CHUMA VILAQUE ITALAQUE SUAPI DE ALTO BENI SAN JUAN DE CANCANI LIQUISANI COLLABAMBA GUANAY COTAPAMPA TEOPONTE PUERTO ACOSTA CHINAÑA 6 SANTA ROSA DE AGOSTO ANANEA CARGUARANI PAUCARES CHAJLAYA BELEN SANTA ANA DEL TAJANI PTO. ESCOMA MUÑECAS130 PANIAGUA ALTO BENI ANBANA TACACOMA PARAJACHI YANI H QUIABAYA LARECAJATIPUANI PALOS BLANCOS L V. PUNI SANTA ROSA DE CHALLANA COLLASUYO SAN MIGUELO CALAMA I EDUARDO AVAROA ELECTRIFIC DE YARICOA TIMUSI OBISPO BOSQUE CALLAPATA SOCOCONI VILLA ELEVACION PTO. CARABUCO CARRASCO LA RESERVAV CHUCHULAYA ANKOMA SAPUCUNI ALTO ILLIMANI ROSARIO 112 SORATA CARRASCO ENTRE RIOS PTO. COMBAYA 115 SAN PABLO CHAGUAYA ILABAYA ALCOCHE NA CHIÑAJA SOREJAYA SANTA FE CARANAVI S VILLA OM A MACA MACA MILLIPAYA ANCORAIMES CHEJE UYUNENSE PAMPA SANTA ANAR DE CARANAVI CAJIATAASFRANZ TAMAYO PTO.RICO SOTALAYA TAYPIPLAYA WARISATA CHOJÑA UYOS COTAPATA SAN JUAN DE CHALLANA CA INCAHUARA DE CKULLO CUCHU ACHACACHI SAN JOSE A V. -

BIBLIOGRAPHIC INPUT SHEET Agricultural Economics

FOR AID USE ONLY AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT WASHINGTON. D. C. 20523 BIBLIOGRAPHIC INPUT SHEET A. PRIMARY I.SUBJECT Economics CLASSI- B. SECONDARY FICATION Agricultural Economics 2. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Optimal allocation of agricultural resources in the development area of Patacamaya,Boliviaa linear programming approach 3. AUTHOR(S) Pou,Claudio 4. DOCUMENT DATE 5 . NUMBER OF PAGES 1. AlC NUg9ER 1972 479p. ARC L-.2. ,- 2 7. REFERENCE ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS Iowa State University Department of Economics Ames Iowa 8. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES (Sponnoting Organization, Publiahere, Availability) 9. ABSI RACT Economic questions such as farm sizes and profits are considered. Farm size is defined as the number of persons on the cooperative farm, actual size of the farm, and the degree of mechanization. The farm size providing the highest income per person in the cooperative is about fourteen bectares per person. If a loss of ten percent income is acceptable, the farm size can be reduced to seven hectares per person. It is more advantageous to raise crops thar sheep, because sheep raising yields lower profits and requires a higher use of labor. Partial mechanization is better for smaller farms, while full mechanization is more profitable in larger farms. This pattern evolves because the smaller farms have a higher land-to-land ratio. Recommendations suggest the renting of land, upgrading of managerial and mechanical skills, standardized record keeping, and availability of an agricultural economists, 10. CONTROL NUMBER II. PRICE OF DOCUMENT Pi-Aa-/ ________ ___ 12. DESCRIPTORS 13. PROJECT NUMBER Farm sizes, Profits, Mechanization, Crops, Sheep, Labor, 931-11-140-124 Land Rental, Record-Keeping, Management 14. -

Bolivia, Su Historia1

Dr. Waldo Albarracín Sánchez RECTOR M.Sc. Alberto Quevedo Iriarte VICERRECTOR M.Sc. Cecilia Salazar de la Torre DIRECTORA - CIDES Obrajes, Av. 14 de Septiembre Nº 4913, esquina Calle 3 Telf/Fax: 591-2-2786169 / 591-2-2784207 591-2-2782361 / 591-2-2785071 [email protected] www.cides.edu.bo Umbrales Nº 29 Bolivianistas La Revista “Umbrales” es una publicación semestral del Postgrado en Ciencias del Desarro- llo, unidad dependiente del Vicerrectorado de la Universidad Mayor de San Andrés. Tiene como misión contribuir al debate académico e intelectual en Bolivia y América Latina, en el marco del rigor profesional y el pluralismo teórico y político, al amparo de los compromisos democráticos, populares y emancipatorios de la universidad pública boliviana. Consejo editorial: Carmen Soliz Cecilia Salazar de la Torre Patricia Urquieta Crespo Coordinadora de la publicación: Carmen Soliz Cuidado de la edición: Patricia Urquieta C. Portada e ilustraciones interiores: Tapa: “Pucara” (Potosí), lámina 15 Interiores: “República Boliviana. Potosí. Indios de Porco y Chayanta. Chola”, lámina 29 (fragmento); “República Boliviana. Potosí. Serro Mineral”, lámina 28. Album de paisajes, tipos humanos y costumbres de Bolivia (1841-1869). Biblioteca Nacional de Bolivia, 1991. © CIDES-UMSA, 2015 Primera edición: diciembre 2015 D.L.: 4-3-27-12 ISSN: 1994-4543 Umbrales (La Paz) ISSN: 1994-4543 Umbrales (La Paz. En línea) Producción: Plural editores Impreso en Bolivia Índice A modo de introducción Carmen Soliz .......................................................................................... 7 Conchos, colores y castas de metales: El lenguaje de la ciencia colonial en la región andina Allison Margaret Bigelow ....................................................................... 15 Los aimaras en la guerra civil de 1899: ¿enemigos o aliados del Partido Liberal? Gabrielle Kuenzli ................................................................................... -

PDTI-Final-2017.Pdf

GOBIERNO AUTÓNOMO DEPARTAMENTAL DE LA PAZ SECRETARIA DEPARTAMENTAL DE PLANIFICACIÓN DEL DESARROLLO DIRECCIÓN DE PLANIFICACIÓN ESTRATÉGICA TERRITORIAL Gobierno Autónomo Departamental de La Paz D.L.: 4-1-551-17 P.O. Félix Patzi Paco, Ph.D. Gobernador del Departamento de La Paz Ricardo Mamani Ortega Secretario General Lic. Héctor Aguilera Ignacio Secretario Departamental de Planificación del Desarrollo Edición Final: Lic. Francisco Agramont Botello Director de Planificación Estratégica Territorial (DPET) Lic. Tania Quilali Erazo Planificadora de Desarrollo Territorial Equipo Técnico de Apoyo: Lic, Javier Angel Flores Valdez Consultor de Línea - Planificador del Desarrollo Lic. Turkel Castedo Berbery Consultor en Línea - Evaluación de Programas y Proyectos de inversión Ing. David Ramiro Quisbert Mujica Profesional 1 VERSIÓN COMPATIBILIZADA Y CONCORDADA CON EL EL PLAN DE DESARROLLO ECONÓMICO Y SOCIAL POR EL MINISTERIO DE PLANIFICACIÓN DEL DESARROLLO (MPD). Publicado por el Servicio Departamental de Autonomías de La Paz - SEDALP AMANECER DE LA CIUDAD DE LA PAZ FOTOGRAFIA: DIRECCIÓN DE COMUNICACIÓN - GADLP PRESENTACIÓN La promulgación de la nueva Ley del Sistema de Planificación Integral del Estado (SPIE) N° 777 elaborada por el Ministerio de Planificación del Desarrollo y promulgada el 21 de enero de 2016 sorprendió no sólo a las distintas Entidades Territoriales Autónomas (ETAs) sino al conjunto de instituciones públicas en general, por la inoportuna sanción de la misma pues la promulgación se la realizó en una etapa en la que ya habían concluido los procesos de elaboración de los planes operativos anuales (POAs) para la gestión 2016 y cuando las ETAs habían comprometido todos sus recursos. La nueva Ley del SPIE impone a todas las ETAs la tarea de elaborar nuevos planes de desarrollo denominados esta vez como Planes Territoriales de Desarrollo Integral (PTDI) para el periodo 2016 -2020 y simultáneamente, obliga a la elaboración de nuevos Planes Estratégicos Institucionales (PEI) en un plazo de 180 días para ambos documentos. -

Educación Superior Y Pueblos Indígenas Y Afrodescendientes En América Latina

www.flacsoandes.edu.ec EDUCACIÓN SUP E RIOR Y PU E BLO S INDÍG E NA S Y AFROD es C E NDI E NT es E N AMÉRICA LATINA NORMA S , POLÍTICA S Y PRÁCTICA S DANI E L MATO COORDINADOR Segunda edición ampliada Caracas 2012 Servicio de Información y Documentación. IESALC-UNESCO. Catalogación en fuente. Educación Superior y Pueblos Indígenas y Afrodescendientes en América Latina. Normas, Políticas y Prácticas / coordinado por Daniel Mato. Segunda edición ampliada. Caracas: IESALC-UNESCO, 2012 1. Argentina. 2. Bolivia. 3. Brasil. 4. Chile. 5. Colombia. 6. Ecuador. 7. Guatemala. 8. México. 9. Nicaragua. 10. Perú I. Mato, Daniel, Coord. © IESALC-UNESCO, 2012 Los resultados, interpretaciones y conclusiones que se expresan en esta publicación corresponden a los autores y no reflejan los puntos de vista oficiales del IESALC-UNESCO. Los términos empleados, así como la presentación de datos, no implican ninguna toma de decisión del Secretariado de la Organización sobre el estatus jurídico de tal o cual país, territorio, ciudad o región, sobre sus autoridades, ni tampoco en lo referente a la delimitación de las fronteras nacionales. Este libro está disponible en el sitio del IESALC-UNESCO: www.iesalc.unesco.org.ve, de donde puede ser descargado de manera gratuita en versión idéntica a la impresa. Instituto Internacional para la Educación Superior en América Latina y el Caribe Javier Botero, Presidente del Consejo de Administración Pedro Henríquez Guajardo, Director Dirección: Edificio Asovincar Av. Los Chorros c/c Calle Acueducto, Altos de Sebucán Apartado Postal 68.394 Caracas 1062-A, Venezuela Teléfono: 58 212 2861020 Fax: 58 212 2860326 Correo electrónico: [email protected] Sitio web: http://www.iesalc.unesco.org.ve Apoyo Técnico: Minerva D’Elía Diseño de carátula: Anhelo M.