Matter of Privilege Referred by the Speaker on 15 April 2020 Relating

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Criminal Law Reform with the Hon Jarrod Bleijie

The Great Leap Backward: Criminal Law Reform with the Hon Jarrod Bleijie Andrew Trotter∗ and Harry Hobbs† Abstract On 3 April 2012, the Honourable Member for Kawana, Jarrod Bleijie MP, was sworn in as Attorney-General for Queensland and Minister for Justice. In the period that followed, Queensland’s youngest Attorney-General since Sir Samuel Griffith in 1874 has implemented substantial reforms to the criminal law as part of a campaign to ‘get tough on crime’. Those reforms have been heavily and almost uniformly criticised by the profession, the judiciary and the academy. This article places the reforms in their historical context to illustrate that together they constitute a great leap backward that unravels centuries of gradual reform calculated to improve the state of human rights in criminal justice. I Introduction Human rights in the criminal law were in a fairly dire state in the Middle Ages.1 Offenders were branded with the letters of their crime to announce it to the public, until that practice was replaced in part by the large scarlet letters worn by some criminals by 1364.2 The presumption of innocence, although developed in its earliest forms in Ancient Rome, does not appear to have crystallised into a recognisable form until 1470.3 During the 16th and 17th centuries, it was common to charge the families of a prisoner sentenced to death a fee for their execution, but ∗ BA LLB (Hons) QUT; Solicitor, Doogue O’Brien George. † BA LLB (Hons) ANU; Human Rights Legal and Policy Adviser, ACT Human Rights Commission. The authors thank Professor the Hon William Gummow AC for his helpful comments on earlier drafts and the editors and anonymous reviewers for their assistance in the final stages. -

Ap2 Final 16.2.17

PALASZCZUK’S SECOND YEAR AN OVERVIEW OF 2016 ANN SCOTT HOWARD GUILLE ROGER SCOTT with cartoons by SEAN LEAHY Foreword This publication1 is the fifth in a series of Queensland political chronicles published by the TJRyan Foundation since 2012. The first two focussed on Parliament.2 They were written after the Liberal National Party had won a landslide victory and the Australian Labor Party was left with a tiny minority, led by Annastacia Palaszczuk. The third, Queensland 2014: Political Battleground,3 published in January 2015, was completed shortly before the LNP lost office in January 2015. In it we used military metaphors and the language which typified the final year of the Newman Government. The fourth, Palaszczuk’s First Year: a Political Juggling Act,4 covered the first year of the ALP minority government. The book had a cartoon by Sean Leahy on its cover which used circus metaphors to portray 2015 as a year of political balancing acts. It focussed on a single year, starting with the accession to power of the Palaszczuk Government in mid-February 2015. Given the parochial focus of our books we draw on a limited range of sources. The TJRyan Foundation website provides a repository for online sources including our own Research Reports on a range of Queensland policy areas, and papers catalogued by policy topic, as well as Queensland political history.5 A number of these reports give the historical background to the current study, particularly the anthology of contributions The Newman Years: Rise, Decline and Fall.6 Electronic links have been provided to open online sources, notably the ABC News, Brisbane Times, The Guardian, and The Conversation. -

2015 Statistical Returns

STATE GENERAL ELECTION Held on Saturday 31 January 2015 Evaluation Report and Statistical Return 2015 State General Election Evaluation Report and Statistical Return Electoral Commission of Queensland ABN: 69 195 695 244 ISBN No. 978-0-7242-6868-9 © Electoral Commission of Queensland 2015 Published by the Electoral Commission of Queensland, October 2015. The Electoral Commission of Queensland has no objection to this material being reproduced, made available online or electronically but only if it is recognised as the owner of the copyright and this material remains unaltered. Copyright enquiries about this publication should be directed to the Electoral Commission of Queensland, by email or in writing: EMAIL [email protected] POST GPO Box 1393, BRISBANE QLD 4001 CONTENTS Page No. Part 1: Foreword ..........................................................................................1 Part 2: Conduct of the Election ....................................................................5 Part 3: Electoral Innovation .......................................................................17 Part 4: Improvement Opportunities............................................................25 Part 5: Statistical Returns ..........................................................................31 Part 6: Ballot Paper Survey .....................................................................483 PART 1 FOREWORD 1 2 PART 1: FOREWORD Foreword The Electoral Commission of Queensland is an independent body charged with responsibility for the impartial -

Human Rights Bill Committee Report

Human Rights Bill 2018 Report No. 26, 56th Parliament Legal Affairs and Community Safety Committee February 2019 Legal Affairs and Community Safety Committee Chair Mr Peter Russo MP, Member for Toohey Deputy Chair Mr James Lister MP, Member for Southern Downs Members Mr Stephen Andrew MP, Member for Mirani Mr Jim McDonald MP, Member for Lockyer Mrs Melissa McMahon MP, Member for Macalister1 Ms Corinne McMillan MP, Member for Mansfield Committee Secretariat Telephone +61 7 3553 6641 Fax +61 7 3553 6699 Email [email protected] Technical Scrutiny +61 7 3553 6601 Secretariat Committee Web Page www.parliament.qld.gov.au/lacsc Acknowledgements The committee acknowledges the assistance provided by the Department of Justice and Attorney- General and the Queensland Parliamentary Library. 1 On 1 November 2018, the Leader of the House appointed the Member for Capalaba, Don Brown MP, as a substitute member of the committee for the Member for Macalister, Melissa McMahon MP, to attend the committee’s public briefing held on Monday 12 November 2018. Human Rights Bill 2018 Contents Abbreviations iii Chair’s foreword v Recommendation vi Introduction 1 Role of the committee 1 Inquiry process 1 Policy objectives of the Bill 1 Government consultation on the Bill 2 Should the Bill be passed? 2 Examination of the Bill 3 Objects of the Act 3 2.1.1 The dialogue model 3 Interpretation 8 2.2.1 Meaning of public entity and when a function is of a public nature 8 2.3 Application of human rights 13 2.3.1 Who has human rights 13 2.3.2 Human rights may be -

Louise Rollman Thesis

CURATING THE CITY: UNPACKING CONTEMPORARY ART PRODUCTION AND SPATIAL POLITICS IN BRISBANE Louise Rollman BA (Visual Arts) (Hons), Queensland University of Technology Principal Supervisor: Professor Andrew McNamara Associate Supervisors: Dr Emma Felton External Associate Supervisor: Dr Gretchen Coombs Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Visual Arts, Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology 2018 Keywords Contemporary art; public art; commissioning for the public realm; curatorial practice; Henri Lefebvre, the right to the city and the right to imagine the city; arts policy infrastructure and institutionalization; cultural history. Curating the City: unpacking contemporary art production and spatial politics in Brisbane i Abstract Contemporary art and exhibition-making is increasingly deployed in the urban development and marketing of cities for political-economic benefit, yet the examination of the aesthetic and cultural aspects of urban life is curiously limited. In probing the unique political conditions of Brisbane, Australia, this thesis contrasts two periods — 1985-1988 and 2012-2015 — in order to more fully understand the critical pressures impacting upon the production of contemporary aesthetic projects. While drawing upon Henri Lefebvre's right to the city, and insisting upon a right to imagine the city, this thesis concludes that a consistent re-articulation of critical pressure, which anticipates oppositional positions, is necessary. Curating the City: unpacking -

Superior Court of California in and for the County of Placer

Superior Court of California in and for the County of Placer Case Index Date Range: 1/1/2020 to 6/30/2020 Index Run Date: 10/30/2020 Case Number Case Type Case Name Party Name Party Type status Confid StatusendDate 2020 Adoptions Adoption (Adult) S-AD-0003890 Adoptions Confidential Case Confidential Case Confidential Case 2/28/2020 2 Adoption (Adult) S-AD-0003890 Adoptions Confidential Case Confidential Case Confidential Case 2/28/2020 2 Adoption (Adult) S-AD-0003896 Adoptions Confidential Case Confidential Case Confidential Case 1/15/2020 2 Adoption (Adult) S-AD-0003901 Adoptions Confidential Case Confidential Case Confidential Case 3/3/2020 2 Adoption (Adult) S-AD-0003901 Adoptions Confidential Case Confidential Case Confidential Case 3/3/2020 2 Adoption (Adult) S-AD-0003902 Adoptions Confidential Case Confidential Case Confidential Case 3/3/2020 2 Adoption (Adult) S-AD-0003902 Adoptions Confidential Case Confidential Case Confidential Case 3/3/2020 2 Adoption (Adult) S-AD-0003951 Adoptions Confidential Case Confidential Case Confidential Case 6/8/2020 2 Adoption (Adult) Adoption (Family) S-AD-0003886 Adoptions Confidential Case Confidential Case Confidential Case 2/7/2020 2 Adoption (Family) S-AD-0003886 Adoptions Confidential Case Confidential Case Confidential Case 2/7/2020 2 Adoption (Family) S-AD-0003887 Adoptions Confidential Case Confidential Case Confidential Case 2/10/2020 2 Adoption (Family) S-AD-0003887 Adoptions Confidential Case Confidential Case Confidential Case 2/10/2020 2 Adoption (Family) S-AD-0003889 Adoptions Confidential -

The Role of Committees in Rights Protection in Federal and State Parliaments in Australia I Introduction

40 UNSW Law Journal Volume 41(1) 3 THE ROLE OF COMMITTEES IN RIGHTS PROTECTION IN FEDERAL AND STATE PARLIAMENTS IN AUSTRALIA LAURA GRENFELL* AND SARAH MOULDS** This article offers a snapshot of how Australian parliamentary committees scrutinise Bills for their rights-compliance in circumstances where the political stakes are high and the rights impacts strong. It tests the assumption that parliamentary models of rights protection are inherently flawed when it comes to Bills directed at electorally unpopular groups such as bikies and terrorists by analysing how parliamentary committees have scrutinised rights-limiting anti-bikie Bills and counter-terrorism Bills. Through these case studies a more nuanced picture emerges, with evidence that, in the right circumstances, parliamentary scrutiny of ‘law and order’ can have a discernible rights-enhancing impact. The article argues that when parliamentary committees engage external stakeholders they can contribute to the development of an emerging culture of rights-scrutiny. While this emerging culture may not yet work to prevent serious intrusions into individual rights, at the federal level there are signs it may at least be capable of moderating these intrusions. I INTRODUCTION Australia has a parliamentary model of rights protection which means that, outside of the protections provided by the Constitution and the common law, most Parliaments in Australia have almost exclusive responsibility for directly protecting the rights of all members of the community. Only in two Australian Parliaments, those of Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory, is this direct * Dr Laura Grenfell is an Associate Professor at the University of Adelaide Law School where she teaches and researches public law and human rights. -

China an Opportunity for Local Businesses

2/10/2019 China an opportunity for local businesses OPPORTUNITY awaits Hinchinbrook businesses in China if they are willing to put the time and effort in to forging strong trade ties, says Hinchinbrook MP Nick Dametto. Speaking after a week-long visit to Shanghai as part of a parliamentary trade delegation, Mr Dametto said there was an “extraordinary” demand for high quality, premium products from Australia in which local businesses could potentially capitalise on. “Instead of selling out to Chinese investors, there is a real opportunity to produce here and partner with Chinese import/distribution companies to fully capitalise on this growing market,” he said. “But you have to be ready to invest in building relationships with the Chinese. Spend your time carefully picking the right business to partner with, and be willing to invest significantly in marketing and packaging and most of all, be ready to supply your product if it takes off. “Although difficult, it’s not impossible to crack the market and is very rewarding with a middle class of an estimated 400 million people. To throw some figures around this, it is said if your new business or product launch isn’t seeing triple figure growth in the first four to five years, that can be interpreted as a floundering or failing product.” Mr Dametto met with representatives from Austrade, Trade and Investment Queensland (TIQ) and multinational e-commerce business Alibaba during his trip, which marked 30 years of the sister-state relationship between Queensland and Shanghai. “Those discussions made it clear to me that the Chinese do not appreciate foreigners who view them as a modern day cash cow and you will have far more success if you treat them as a friend,” he said. -

221284 Law Journal Text

LEARNING FROM EXPERIENCE: INTERPRETING THE INTERPRETIVE PROVISIONS IN AUSTRALIAN HUMAN RIGHTS LEGISLATION * BENEDICT COXON Human rights legislation in the Australian Capital Territory (‘ACT’), Victoria and Queensland contains interpretive provisions to the effect that legislation is to be interpreted consistently or compatibly with the rights set out in the relevant statute. This article is an attempt to analyse these interpretive provisions as a matter of statutory interpretation; that is, the rules of statutory interpretation are applied to the interpretive provisions. Courts in the ACT and Victoria have interpreted the provisions as conferring modest powers, similar to the common law principle of legality. As a matter of the application of the principles of statutory interpretation, this appears to be the correct approach. Queensland courts may be expected to follow their ACT and Victorian counterparts in this respect. I INTRODUCTION The Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld) (‘QHRA’) came fully into force on 1 January 2020.1 The QHRA is modelled on the Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic) (‘Charter’) and the Australian Capital Territory’s Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT) (‘ACTHRA’).2 Each of these statutes contains an interpretive provision to the effect that legislation is to be interpreted consistently or compatibly with the rights set out in the statute.3 There is as yet little literature on the QHRA.4 The literature on the Victorian and Australian Capital Territory (‘ACT’) legislation tends to adopt the perspective * Honorary Research Fellow, University of Western Australia Law School. 1 Proclamation, Subordinate Legislation 2019 No 224 (14 November 2019). Certain provisions came into force earlier, on 1 July 2019: Proclamation, Subordinate Legislation 2019 No 97 (13 June 2019). -

Electoral (Voter's Choice) Amendment Bill 2019

Electoral (Voter's Choice) Amendment Bill 2019 Report No. 62, 56th Parliament Legal Affairs and Community Safety Committee March 2020 Legal Affairs and Community Safety Committee Chair Mr Peter Russo MP, Member for Toohey Deputy Chair Mr James Lister MP, Member for Southern Downs Members Mr Stephen Andrew MP, Member for Mirani Mr Jim McDonald MP, Member for Lockyer Mrs Melissa McMahon MP, Member for Macalister Ms Corrine McMillan MP, Member for Mansfield Committee Secretariat Telephone +61 7 3553 6641 Fax +61 7 3553 6699 Email [email protected] Technical Scrutiny +61 7 3553 6601 Secretariat Committee Web Page www.parliament.qld.gov.au/lacsc Acknowledgements The committee acknowledges the assistance provided by Mr David Janetzki MP, Member for Toowoomba South, Shadow Attorney-General and Shadow Minister for Justice. Electoral (Voter's Choice) Amendment Bill 2019 Contents Abbreviations iii Chair’s foreword v Recommendation vi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Role of the committee 1 1.2 Inquiry process 1 1.3 Policy objective of the Bill 1 1.4 Private Member consultation on the Bill 2 1.5 Should the Bill be passed? 2 2 History of voting systems in Queensland 3 2.1 Types of voting systems 3 2.1.1 First-past-the-post 3 2.1.2 Optional preferential 3 2.1.3 Full (compulsory) preferential 4 2.2 Queensland’s history of voting systems 4 2.2.1 1860-1892 4 2.2.2 1892-1942 4 2.2.3 1942-1962 4 2.2.4 1962-1992 5 2.2.5 1992-2016 5 2.2.6 2016-present 5 3 Examination of the Bill 6 3.1 Background 6 3.2 The Bill 6 3.3 Advantages of optional preferential voting -

6451 George Street @Queensland Parliamentary Service Brisbane Qld 4000 Email: [email protected]

ETHICS COMMITTEE REPORT NO. 198 MATTER OF PRIVILEGE REFERRED BY THE REGISTRAR ON 16 OCTOBER 2019 RELATING TO AN ALLEGED FAILURE TO REGISTER AN INTEREST IN THE REGISTER OF MEMBERS’ INTERESTS Introduction and background 1. The Ethics Committee (the committee) is a statutory committee of the Queensland Parliament established under section 102 of the Parliament of Queensland Act 2001 (‘the POQA’). The current committee was appointed by resolution of the Legislative Assembly on 15 February 2018. 2. The committee’s area of responsibility includes dealing with complaints about the ethical conduct of particular members and dealing with alleged breaches of parliamentary privilege by members of the Assembly and other persons.1 The committee investigates and reports on matters of privilege and possible contempts of Parliament referred to it by the Speaker, the Registrar, or the House. 3. This report concerns a referral from the Registrar regarding a possible contempt of Parliament by the Member for Broadwater, Mr David Crisafulli MP for failing to declare interests on the Register of Members’ Interests. The referral 4. On 15 October 2019, the Leader of the House, Hon Yvette D’Ath MP wrote to the Registrar (the Clerk of the Parliament) alleging that the Member for Broadwater, Mr David Crisafulli MP, failed to declare, within the required timeframe, that he was director of Revalot Pty Ltd on the Register of Members’ Interests (‘the Register’). It was further alleged that he failed to declare, whatsoever, that he was secretary of Revalot Pty Ltd. 5. The Leader of the House also noted a property at Lannercost had recently appeared on the Member for Broadwater’s statement of interests, and queried if it had been declared within the required time frame. -

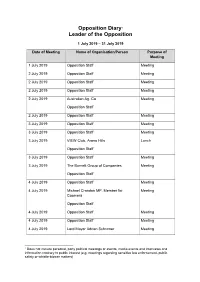

Extracts from the Leader of the Opposition Diary

Opposition Diary1 Leader of the Opposition 1 July 2019 – 31 July 2019 Date of Meeting Name of Organisation/Person Purpose of Meeting 1 July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 2 July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 2 July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 2 July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 2 July 2019 Australian Ag. Co Meeting Opposition Staff 2 July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 3 July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 3 July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 3 July 2019 VIEW Club, Arana Hills Lunch Opposition Staff 3 July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 3 July 2019 The Burnett Group of Companies Meeting Opposition Staff 4 July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 4 July 2019 Michael Crandon MP, Member for Meeting Coomera Opposition Staff 4 July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 4 July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 4 July 2019 Lord Mayor Adrian Schrinner Meeting 1 Does not include personal, party political meetings or events, media events and interviews and information contrary to public interest (e.g. meetings regarding sensitive law enforcement, public safety or whistle-blower matters) Date of Meeting Name of Organisation/Person Purpose of Meeting Opposition Staff 4 July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 4 July 2019 Auscript Meeting Opposition Staff 4 July 2019 Granite Belt Irrigation Project Steering Meeting Committee James Lister MP, Member for Southern Downs Opposition Staff 5 July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 6 July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 6 July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 7July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 8 July 2019 Opposition Staff Meeting 9 July