221284 Law Journal Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life Education Queensland 2019 Annual Report

Life Education Queensland ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Empowering our children and young people to make safer and healthier choices through education Contents Our patrons 1 From the chairman 2 From the CEO 3 About Life Education 5 Our reach 6 Face-to-face delivery 8 Our programs 10 Indigenous communities 16 School & community partnerships 17 Our impact 18 Media coverage 22 Educator reflections 24 40-year celebration 26 Our fundraising 28 Our committees 30 Our ambassadors 34 Our partners 36 Our governance 37 Our team 38 Our financials 39 LIFE EDUCATION QUEENSLAND Annual Report 2019 Our patrons The Honourable Robert Borbidge AO The Honourable Dr Anthony Lynham The Honourable Robert Borbidge AO was the 35th premier of The Honourable Dr Anthony Lynham is the Minister for Queensland and served in the State Parliament as Member for Natural Resources, Mines and Energy. Before entering Surfers Paradise for more than 20 years. parliament as the Member for Brisbane seat of Stafford in 2014, Dr Lynham worked as a maxillofacial surgeon. As During this time, he held several senior positions including a surgeon who continuously dealt with the aftermath of senior ministries, deputy leader of the Opposition, leader of the violence, Dr Lynham was a prominent advocate of policies Opposition and premier. to minimise alcohol-fuelled violence, prior to entering Since his resignation from parliament in 2001, he has held parliament. numerous board positions in both private and publicly-listed Dr Lynham graduated in medicine from the University companies. of Newcastle and completed his maxillofacial surgery In 2006 Mr Borbidge was appointed an Officer of the Order training in Queensland. -

Extracts from the Leader of the Opposition Diary

Opposition Diary1 Leader of the Opposition 1 November 2020 – 30 November 2020 Date of Meeting Name of Organisation/Person Purpose of Meeting Following the result of the general election on 31 October 2020, a new Leader of the Opposition was elected on 12 November 2020. 15 November 2020 David Janetzki MP, Deputy Leader of the Meeting Opposition, Shadow Treasurer, Shadow Minister for Investment and Trade, Member for Toowoomba South Laura Gerber MP, Shadow Assistant Minister for Justice, Shadow Assistant Minister for Youth, Shadow Assistant Minister for the Night-time Economy, Shadow Assistant Minister for Cultural Development, Member for Currumbin Amanda Camm MP, Shadow Minister for Child Protection, Shadow Minister for the Prevention of Domestic, Family and Sexual Violence, Member for Whitsunday Sam O’Connor MP, Shadow Minister for Environment and the Great Barrier Reef, Shadow Minister for Science and Innovation, Shadow Minister for Youth, Member for Bonney Brent Mickelberg MP, Shadow Minister for Employment, Small Business and Training, Shadow Minister for Open Data, Member for Buderim Opposition Staff 16 November 2020 Jarrod Bleijie MP, Shadow Minister for Meeting Finance, Shadow Minister for Industrial Relations, Manager of Opposition Business, Member for Kawana 1 Does not include personal, party political meetings or events, media events and interviews and information contrary to public interest (e.g. meetings regarding sensitive law enforcement, public safety or whistle-blower matters) Date of Meeting Name of Organisation/Person -

2015 Statistical Returns

STATE GENERAL ELECTION Held on Saturday 31 January 2015 Evaluation Report and Statistical Return 2015 State General Election Evaluation Report and Statistical Return Electoral Commission of Queensland ABN: 69 195 695 244 ISBN No. 978-0-7242-6868-9 © Electoral Commission of Queensland 2015 Published by the Electoral Commission of Queensland, October 2015. The Electoral Commission of Queensland has no objection to this material being reproduced, made available online or electronically but only if it is recognised as the owner of the copyright and this material remains unaltered. Copyright enquiries about this publication should be directed to the Electoral Commission of Queensland, by email or in writing: EMAIL [email protected] POST GPO Box 1393, BRISBANE QLD 4001 CONTENTS Page No. Part 1: Foreword ..........................................................................................1 Part 2: Conduct of the Election ....................................................................5 Part 3: Electoral Innovation .......................................................................17 Part 4: Improvement Opportunities............................................................25 Part 5: Statistical Returns ..........................................................................31 Part 6: Ballot Paper Survey .....................................................................483 PART 1 FOREWORD 1 2 PART 1: FOREWORD Foreword The Electoral Commission of Queensland is an independent body charged with responsibility for the impartial -

Human Rights Bill Committee Report

Human Rights Bill 2018 Report No. 26, 56th Parliament Legal Affairs and Community Safety Committee February 2019 Legal Affairs and Community Safety Committee Chair Mr Peter Russo MP, Member for Toohey Deputy Chair Mr James Lister MP, Member for Southern Downs Members Mr Stephen Andrew MP, Member for Mirani Mr Jim McDonald MP, Member for Lockyer Mrs Melissa McMahon MP, Member for Macalister1 Ms Corinne McMillan MP, Member for Mansfield Committee Secretariat Telephone +61 7 3553 6641 Fax +61 7 3553 6699 Email [email protected] Technical Scrutiny +61 7 3553 6601 Secretariat Committee Web Page www.parliament.qld.gov.au/lacsc Acknowledgements The committee acknowledges the assistance provided by the Department of Justice and Attorney- General and the Queensland Parliamentary Library. 1 On 1 November 2018, the Leader of the House appointed the Member for Capalaba, Don Brown MP, as a substitute member of the committee for the Member for Macalister, Melissa McMahon MP, to attend the committee’s public briefing held on Monday 12 November 2018. Human Rights Bill 2018 Contents Abbreviations iii Chair’s foreword v Recommendation vi Introduction 1 Role of the committee 1 Inquiry process 1 Policy objectives of the Bill 1 Government consultation on the Bill 2 Should the Bill be passed? 2 Examination of the Bill 3 Objects of the Act 3 2.1.1 The dialogue model 3 Interpretation 8 2.2.1 Meaning of public entity and when a function is of a public nature 8 2.3 Application of human rights 13 2.3.1 Who has human rights 13 2.3.2 Human rights may be -

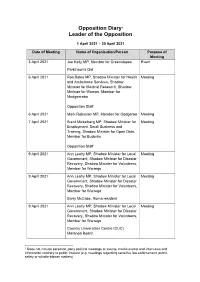

Extracts from the Leader of the Opposition Diary

Opposition Diary1 Leader of the Opposition 1 April 2021 – 30 April 2021 Date of Meeting Name of Organisation/Person Purpose of Meeting 3 April 2021 Joe Kelly MP, Member for Greenslopes Event Parkinson’s Qld 6 April 2021 Ros Bates MP, Shadow Minister for Health Meeting and Ambulance Services, Shadow Minister for Medical Research, Shadow Minister for Women, Member for Mudgeeraba Opposition Staff 6 April 2021 Mark Robinson MP, Member for Oodgeroo Meeting 7 April 2021 Brent Mickelberg MP, Shadow Minister for Meeting Employment, Small Business and Training, Shadow Minister for Open Data, Member for Buderim Opposition Staff 9 April 2021 Ann Leahy MP, Shadow Minister for Local Meeting Government, Shadow Minister for Disaster Recovery, Shadow Minister for Volunteers, Member for Warrego 9 April 2021 Ann Leahy MP, Shadow Minister for Local Meeting Government, Shadow Minister for Disaster Recovery, Shadow Minister for Volunteers, Member for Warrego Barry McCabe, Roma resident 9 April 2021 Ann Leahy MP, Shadow Minister for Local Meeting Government, Shadow Minister for Disaster Recovery, Shadow Minister for Volunteers, Member for Warrego Country Universities Centre (CUC) Maranoa Board 1 Does not include personal, party political meetings or events, media events and interviews and information contrary to public interest (e.g. meetings regarding sensitive law enforcement, public safety or whistle-blower matters) Date of Meeting Name of Organisation/Person Purpose of Meeting 9 April 2021 Ann Leahy MP, Shadow Minister for Local Meeting Government, Shadow -

1 Queensland 57Th Parliament 2020-2024 Information Taken From

1 Queensland 57th Parliament 2020-2024 Information taken from: https://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/members/current See also: the Ministerial Charter Letters (MCL) outlining the Government’s priorities, that each Minister (and Assistant Minister) is responsible for delivering over this term of government, were uploaded to the QLD Government website on 1 December 2020. The Ministerial Charter Letters’ also include the election commitments that each Minister (and Assistant Minister) is responsible for delivering. Link: https://cabinet.qld.gov.au/ministers/charter-letters.aspx Ministerial Portfolios Shadow Minister Portfolios Name & Address Email & Phone ALP Name & Address Email & Phone LNP Portfolio Electorate Portfolio Electorate Hon PO Box Phone: 3719 7000 Inala Mr David PO Box Phone: (07) 3838 6767 Broadwater Annastacia 15185, Crisafulli 15057 Palasczuk City East Email: Leader of the CITY EAST Email: Premier & Qld 4002 [email protected] Opposition & QLD 4002 [email protected] Minister for u Shadow Minister for Tourism Trade Mr David Janetzki [email protected] Shadow Minister for Investment and Trade Hon Dr Steven PO Box Phone: (07) 3719 7100 Murrumba Mr David Janetzki PO Box Phone: (07) 5351 6100 Lockyer Miles 15009 Fax: n/a Deputy Leader of 3005 Fax: n/a Deputy CITY EAST Email: the Opposition, TOOWOOM Email: Premier and QLD 4002 deputy.premier@Bleijieministeri Ms Fiona BA QLD [email protected] Minister for al.qld.gov.au Simpson Shadow 4350 State Minister for State Development, Development -

Electoral (Voter's Choice) Amendment Bill 2019

Electoral (Voter's Choice) Amendment Bill 2019 Report No. 62, 56th Parliament Legal Affairs and Community Safety Committee March 2020 Legal Affairs and Community Safety Committee Chair Mr Peter Russo MP, Member for Toohey Deputy Chair Mr James Lister MP, Member for Southern Downs Members Mr Stephen Andrew MP, Member for Mirani Mr Jim McDonald MP, Member for Lockyer Mrs Melissa McMahon MP, Member for Macalister Ms Corrine McMillan MP, Member for Mansfield Committee Secretariat Telephone +61 7 3553 6641 Fax +61 7 3553 6699 Email [email protected] Technical Scrutiny +61 7 3553 6601 Secretariat Committee Web Page www.parliament.qld.gov.au/lacsc Acknowledgements The committee acknowledges the assistance provided by Mr David Janetzki MP, Member for Toowoomba South, Shadow Attorney-General and Shadow Minister for Justice. Electoral (Voter's Choice) Amendment Bill 2019 Contents Abbreviations iii Chair’s foreword v Recommendation vi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Role of the committee 1 1.2 Inquiry process 1 1.3 Policy objective of the Bill 1 1.4 Private Member consultation on the Bill 2 1.5 Should the Bill be passed? 2 2 History of voting systems in Queensland 3 2.1 Types of voting systems 3 2.1.1 First-past-the-post 3 2.1.2 Optional preferential 3 2.1.3 Full (compulsory) preferential 4 2.2 Queensland’s history of voting systems 4 2.2.1 1860-1892 4 2.2.2 1892-1942 4 2.2.3 1942-1962 4 2.2.4 1962-1992 5 2.2.5 1992-2016 5 2.2.6 2016-present 5 3 Examination of the Bill 6 3.1 Background 6 3.2 The Bill 6 3.3 Advantages of optional preferential voting -

VAD Law Reform Hangs in the Balance STATEMENT by the MY LIFE MY Sound Evidence for VAD Laws, CHOICE COALITION PARTNERS: What We Asked

MY LIFE MY CHOICE QUEENSLAND STATE ELECTION CANDIDATES’ ATTITUDES TO VOLUNTARY ASSISTED DYING 19 OCTOBER 2020 VAD law reform hangs in the balance STATEMENT BY THE MY LIFE MY sound evidence for VAD laws, CHOICE COALITION PARTNERS: What we asked...... would be invaluable to any future debate. So too would the This report canvasses the results other Health Committee MPs of a survey by the My Life My The My Life My Choice partners asked candidates two questions who supported the majority Choice coalition which attempted findings: Joan Pease (Lytton); to determine the strength of to record attitudes to voluntary Michael Berkman (Maiwar); and their support for voluntary assisted dying (VAD) law reform Barry O’Rourke (Rockhampton). assisted dying. held by close to 600 candidates it is too late after polls close for standing at the 31 October Our belief in the value of having voters to discover that their MP QUESTION 1: Do you, as a Queensland election. present in parliament MPs for 2020-2024 will not support a matter of principle support involved in an inquiry into Several factors mean the survey VAD Bill. the right of Queenslanders matters of vital public policy is to have the choice of had a less than full response. We The passage of any VAD Bill will validated by an examination of seeking access to a system recognise that candidates can be depend on having a majority the fate of the inquiry into of voluntary assisted dying inundated with surveys before among 93 MPs willing to palliative care conducted by the elections. -

Industrial Relations Fair Work (Restoring Fairness and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2015 No 4 2015 55Th Parliamentary Debate

INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS FAIR WORK (RESTORING FAIRNESS AND OTHER LEGISLATION AMENDMENT BILL 2015 NO 4 2015 55TH PARLIAMENTARY DEBATE MP SPEAKERS FOR MP SPEAKERS AGAINST CURTIS PITT MP (MEMBER FOR MULGRAVE) ALP IAN WALKER MP (MEMBER FOR MANSFIELD) LNP DI FARMER MP (MEMBER FOR BULIMBA) ALP FIONA SIMPSON MP (MEMBER FOR MAROOCHYDORE) LNP JENNIFER HOWARD MP (MEMBER FOR IPSWICH) ALP VERITY BARTON MP (MEMBER FOR BROADWATER) LNP GRACE GRACE MP (MEMBER FOR BRISBANE CENTRAL) ALP PAT WEIR MP (MEMBER FOR CONDAMINE) LNP CRAIG CRAWFORD MP (MEMBER FOR BARRON RIVER) ALP CHRISTIAN ROWAN MP (MEMBER FOR MOGGILL) LNP BRUCE SAUNDERS MP (MEMBER FOR MARYBOROUGH) ALP ANTHONY PERRETT MP (MEMBER FOR GYMPIE) LNP CHRIS WHITING MP (MEMBER FOR MURRUMBA) ALP DEBORAH FRECKLINGTON MP (MEMBER FOR NANANGO) LNP SHANNON FENTIMAN MP (MEMBER FOR WATERFORD) ALP TIM MANDER MP (MEMBER FOR EVERTON) LNP ROBERT PYNE MP (MEMBER FOR CAIRNS) ALP JAN STUCKEY MP (MEMBER FOR CURRUMBIN) LNP LEANNE LINARD MP (MEMBER FOR NUDGEE) ALP GLEN ELMES MP (MEMBER FOR NOOSA) LNP CAMERON DICK MP (MEMBER FOR WOODRIDGE) ALP MARK MCCARDLE MP (MEMBER FOR CALOUNDRA) LNP SCOTT STEWART MP (MEMBER FOR TOWNSVILLE) ALP TARNYA SMITH MP (MEMBER FOR MT OMMANEY) LNP DUNCAN PEGG MP (MEMBER FOR STRETTON) ALP LAWRENCE SPRINGBORG MP (OPPOSITION LEADER AND MEMBER FOR SOUTHERN DOWNS) LNP DON BROWN MP (MEMBER FOR CAPALABA) ALP JOE KELLY MP (MEMBER FOR GREENSLOPES) ALP STEVEN MILES MP (MEMBER FOR MT COOTHA) ALP NIKKI BOYD MP (MEMBER FOR PINE RIVERS) ALP BILLY GORDON MP (MEMBER FOR COOK) IND MARK FURNER MP (MEMBER FOR FERNY -

Parliamentary Committee's Inquiry Into the Strategic Review of the Office Of

Inquiry into the Strategic Review of the Office of the Queensland Ombudsman Report No. 25, 56th Parliament Legal Affairs and Community Safety Committee November 2018 Legal Affairs and Community Safety Committee Chair Mr Peter Russo MP, Member for Toohey, Chair Deputy Chair Mr James Lister MP, Member for Southern Downs, Deputy Chair Members Mr Stephen Andrew MP, Member for Mirani Mr Jim McDonald MP, Member for Lockyer Mrs Melissa McMahon MP, Member for Macalister Ms Corrine McMillan MP, Member for Mansfield Committee Secretariat Telephone +61 7 3553 6641 Fax +61 7 3553 6699 Email [email protected] Committee webpage www.parliament.qld.gov.au/lacsc Acknowledgements The committee acknowledges the assistance provided by the Reviewer, Ms Simone Webbe, and the Queensland Ombudsman and the staff of the Office of the Queensland Ombudsman. Inquiry into the Strategic Review of the Office of the Queensland Ombudsman Contents Abbreviations ii Chair’s foreword iii Recommendation iv 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The committee 1 1.2 Strategic reviews of the Office of the Ombudsman 1 1.3 2017 strategic review 1 1.3.1 Scope 1 1.3.2 Methodology 2 1.3.3 Strategic review report 3 1.3.4 Response of the Ombudsman to the strategic review report 4 1.4 The committee’s inquiry into the strategic review report 4 2 The strategic review report 5 2.1 Proposed legislative change supported by Reviewer and Ombudsman 5 2.1.1 Widening the scope of preliminary inquiries beyond complaints 5 2.1.2 Ability to formally refer a matter and monitor an investigation undertaken by -

The Lnp Shadow Cabinet 2020

THE LNP SHADOW CABINET 2020 David Crisafulli - Leader of the Opposition, Shadow Minister for Tourism Previously: Shadow Minister for Environment, Science and the Great Barrier Reef and Shadow Minister for Tourism David Janetzki - Deputy Leader of the Opposition, Shadow Treasurer, Shadow Minister for Investment and Trade Previously: Shadow Attorney-General, Shadow Minister for Justice Ros Bates - Shadow Minister for Health and Ambulance Services, Shadow Minister for Medical Research, Shadow Minister for Women Previously: Shadow Minister for Health and Ambulance Services, Shadow Minister for Women Jarrod Bleijie - Shadow Minister for Finance, Shadow Minister for Industrial Relations, Manager of Opposition Business Previously: Shadow Minister for Education, Shadow Minister for Industrial Relations, Manager of Opposition Business Fiona Simpson - Shadow Minister for Integrity in Government, Shadow Minister for State Development and Planning Previously: Shadow Minister for Employment and Small Business, Shadow Minister for Training and Skills Development Dale Last - Shadow Minister for Police and Corrective Services, Shadow Minister for Fire and Emergency Services, Shadow Minister for Rural and Regional Affairs Previously: Shadow Minister for Natural Resources and Mines, Shadow Minister for North Queensland Steve Minnikin - Shadow Minister for Customer Service, Shadow Minister for Transport and Main Roads Previously: Shadow Minister for Transport and Main Roads Tim Nicholls - Shadow Attorney-General, Shadow Minister for Justice Previously: -

Report Template

Consideration of the recommendations of the strategic review of the Queensland Audit Office Report No. 51, 55th Parliament Finance and Administration Committee October 2017 Finance and Administration Committee Chair Mr Peter Russo MP, Member for Sunnybank Deputy Chair Mr Ray Stevens MP, Member for Mermaid Beach Members Mr David Janetzki MP, Member for Toowoomba South Mrs Jo-Ann Miller MP, Member for Bundamba Mr Steve Minnikin MP, Member for Chatsworth Mr Linus Power MP, Member for Logan Committee Secretariat Telephone +61 7 3553 6637 Fax +61 7 3553 6699 Email [email protected] Technical Scrutiny +61 7 3553 6601 Secretariat Committee Web Page www.parliament.qld.gov.au/FAC Acknowledgements The committee acknowledges the assistance provided by Ms Philippa Smith and Mr Graham Carpenter, current and former staff of the Queensland Audit Office and the Treasurer. Consideration of the recommendations of the strategic review of the Queensland Audit Office Contents Abbreviations ii Chair’s foreword iii Recommendations iv 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Role of the committee 1 2 The Queensland Audit Office 1 2.1 Financial audit 2 2.2 Performance audit 2 3 Strategic review of the Queensland Audit Office 3 3.1 Committee consideration of the strategic review report 5 4 Strategic recommendations 6 4.1 Relationship with audit clients 7 4.2 Resources – financial audit 9 Financial audit – fees 10 Impacts upon staff 11 4.3 Performance audit 13 Strategic audit planning 15 Implementation of performance audit recommendations 16 4.4 The QAO’s ability to recruit,