State Irormal School of Colorado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ballads of the Southern Mountains and the Escape from Old Europe

B AR B ARA C HING Happily Ever After in the Marketplace: The Ballads of the Southern Mountains and the Escape from Old Europe Between 1882 and 1898, Harvard English Professor Francis J. Child published The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, a five volume col- lection of ballad lyrics that he believed to pre-date the printing press. While ballad collections had been published before, the scope and pur- ported antiquity of Child’s project captured the public imagination; within a decade, folklorists and amateur folk song collectors excitedly reported finding versions of the ballads in the Appalachians. Many enthused about the ‘purity’ of their discoveries – due to the supposed isolation of the British immigrants from the corrupting influences of modernization. When Englishman Cecil Sharp visited the mountains in search of English ballads, he described the people he encountered as “just English peasant folk [who] do not seem to me to have taken on any distinctive American traits” (cited in Whisnant 116). Even during the mid-century folk revival, Kentuckian Jean Thomas, founder of the American Folk Song Festival, wrote in the liner notes to a 1960 Folk- ways album featuring highlights from the festival that at the close of the Elizabethan era, English, Scotch, and Scotch Irish wearied of the tyranny of their kings and spurred by undaunted courage and love of inde- pendence they braved the perils of uncharted seas to seek freedom in a new world. Some tarried in the colonies but the braver, bolder, more venturesome of spirit pressed deep into the Appalachians bringing with them – hope in their hearts, song on their lips – the song their Anglo-Saxon forbears had gathered from the wander- ing minstrels of Shakespeare’s time. -

INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, Day Department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 Points)

The elective discipline «INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, day department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 points) Task: Select one British folk ballad from the list below, write your name, perform your individual scientific research paper in writing according to the given scheme and hand your work in to the teacher: Titles of British Folk Ballads Students’ Surnames 1. № 58: “Sir Patrick Spens” 2. № 13: “Edward” 3. № 84: “Bonny Barbara Allen” 4. № 12: “Lord Randal” 5. № 169:“Johnie Armstrong” 6. № 243: “James Harris” / “The Daemon Lover” 7. № 173: “Mary Hamilton” 8. № 94: “Young Waters” 9. № 73:“Lord Thomas and Annet” 10. № 95:“The Maid Freed from Gallows” 11. № 162: “The Hunting of the Cheviot” 12. № 157 “Gude Wallace” 13. № 161: “The Battle of Otterburn” 14. № 54: “The Cherry-Tree Carol” 15. № 55: “The Carnal and the Crane” 16. № 65: “Lady Maisry” 17. № 77: “Sweet William's Ghost” 18. № 185: “Dick o the Cow” 19. № 186: “Kinmont Willie” 20. № 187: “Jock o the Side” 21. №192: “The Lochmaben Harper” 22. № 210: “Bonnie James Campbell” 23. № 37 “Thomas The Rhymer” 24. № 178: “Captain Car, or, Edom o Gordon” 25. № 275: “Get Up and Bar the Door” 26. № 278: “The Farmer's Curst Wife” 27. № 279: “The Jolly Beggar” 28. № 167: “Sir Andrew Barton” 29. № 286: “The Sweet Trinity” / “The Golden Vanity” 30. № 1: “Riddles Wisely Expounded” 31. № 31: “The Marriage of Sir Gawain” 32. № 154: “A True Tale of Robin Hood” N.B. You can find the text of the selected British folk ballad in the five-volume edition “The English and Scottish Popular Ballads: five volumes / [edited by Francis James Child]. -

01 Prelude | | |--02 City of Refuge | | |--03 Bring Me My Queen

|--Abigail Washburn | |--City of Refuge | | |--01 Prelude | | |--02 City of Refuge | | |--03 Bring Me My Queen | | |--04 Chains | | |--05 Ballad of Treason | | |--06 Last Train | | |--07 Burn Thru | | |--08 Corner Girl | | |--09 Dreams Of Nectar | | |--10 Divine Bell | | |--11 Bright Morning Stars | | |--cover | | `--folder | |--Daytrotter Studio | | |--01 City of Refuge | | |--02 Taiyang Chulai | | |--03 Bring Me My Queen | | |--04 Chains | | |--06 What Are They Doing | | `--07 Keys to the Kingdom | |--Live at Ancramdale | | |--01 Main Stageam Set | | |--02 Intro | | |--03 Fall On My Knees | | |--04 Coffee’s Cold | | |--05 Eve Stole The Apple | | |--06 Red & Blazey | | |--07 Journey Home | | |--08 Key To The Kingdom | | |--09 Sometime | | |--10 Abigail talks about the trip to Tibet | | |--11 Song Of The Traveling Daughter | | |--12 Crowd _ Band Intros | | |--13 The Sparrow Watches Over Me | | |--14 Outro | | |--15 Master's Workshop Stage pm Set | | |--16 Tuning, Intro | | |--17 Track 17 of 24 | | |--18 Story about Learning Chinese | | |--19 The Lost Lamb | | |--20 Story About Chinese Reality TV Show | | |--21 Deep In The Night | | |--22 Q & A | | |--23 We’re Happy Working Under The Sun | | |--24 Story About Trip To China | | |--index | | `--washburn2006-07-15 | |--Live at Ballard | | |--01 Introduction | | |--02 Red And Blazing | | |--03 Eve Stole The Apple | | |--04 Free Internet | | |--05 Backstep Cindy_Purple Bamboo | | |--06 Intro. To The Lost Lamb | | |--07 The Lost Lamb | | |--08 Fall On My Knees | | |--Aw2005-10-09 | | `--Index -

The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border

*> THE MINSTRELSY OF THE SCOTTISH BORDER — A' for the sake of their true loves : I ot them they'll see nae mair. See />. 4. The ^Minstrelsy of the Scottish "Border COLLECTED BY SIR WALTER SCOTT EDITED AND ARRANGED WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY ALFRED NOYES AND SIX ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOHN MACFARLANE NEW YORK FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY PUBLISHERS • • * « * TO MARGARET AND KATHARINE BRUCE THIS EDITION OF A FAMOUS BOOK OF THEIR COUNTRY IS DEDICATED WITH THE BEST WISHES OF ITS EDITOR :593:3£>3 CONTENTS l'AGE Sir Patrick Spens I 6 The Wife of Usher's Well Clerk Saunders . 9 The Tvva Corbies 15 Barthram's Dirge 16 The Broom of Cowdenknows iS The Flowers of the Forest 23 25 The Laird of Muirhead . Hobbie Noble 26 Graeme and Bewick 32 The Douglas Tragedy . 39 The Lament of the Border Widow 43 Fair Helen 45 Fause Foodrage . 47 The Gay Goss-Hawk 53 60 The Silly Blind Harper . 64 Kinmont Willie . Lord Maxwell's Good-night 72 The Battle of Otterbourne 75 O Tell Me how to Woo Thee 81 The Queen's Marie 83 A Lyke-Wake Dirge 88 90 The Lass of Lochroyan . The Young Tamlane 97 vii CONTENTS PACE 1 The Cruel Sister . 08 Thomas the Rhymer "3 Armstrong's Good-night 128 APPENDIX Jellon Grame 129 Rose the Red and White Lilly 133 O Gin My Love were Yon Red Rose 142 Annan Water 143 The Dowie Dens of Yarrow .46 Archie of Ca'field 149 Jock o' the Side . 154 The Battle of Bothwell Bridge 160 The Daemon-Lover 163 Johnie of Breadislee 166 Vlll LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS "A' for the sake of their true loves ;") ^ „, .,,/". -

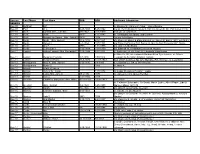

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P

Section Last Name First Name DOB DOD Additional Information BEEMAN Bee-09 Huffman E.P. m. Eleanor R. Clark 5-21-1866; stone illegible Bee-09 Purl J. C. 8-25-1898 5-25-1902 s/o Dr. Henry Bosworth & Laura Purl; b/o Aileen B. (Dr. Purl buried in CA) Bee-10 Buck Cynthia (Mrs. John #2) 2-6-1842 11-6-1930 2nd wife of John Buck Bee-10 Buck John 1807 3-25-1887 m.1st-Magdalena Spring; 2nd-Cynthia Bee-10 Buck Magdalena Spring (Mrs. John #1) 1805 1874 1st w/o John Buck Bee-10 Burris Ida B. (Mrs. James) 11-6-1858 2/12/1927 d/o Moses D. Burch & Efamia Beach; m. James R. Burris 1881; m/o Ora F. Bee-10 Burris James I. 5-7-1854 11/8/1921 s/o Robert & Pauline Rich Burris; m. Ida; f/o Son-Professor O.F. Burris Bee-10 Burris Ora F. 1886 2-11-1975 s/o James & Ida Burris Bee-10 Burris Zelma Ethel 7-15-1894 1-18-1959 d/o Elkanah W. & Mahala Ellen Smith Howard Bee-11 Lamkin Althea Leonard (Mrs. Benjamin F.) 7-15-1844 3/17/1931 b. Anderson, IN; d/o Samuel & Amanda Eads Brown b. Ohio Co, IN ; s/o Judson & Barbara Ellen Dyer Lamkin; m. Althea Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Franklin 1-7-1836 1/30/1914 Leonard; f/o Benjamin Franklin Lamkin Bee-11 Lamkin Benjamin Frank 11-9-1875 12-17-1943 Son of B.F. & Althea; Sp. Am. War Mo., Pvt. -

Medieval Ballads Instructor

Topic: Medieval Ballads Instructor: Mrs. Tincher Date: 26 Sept. 2011 Age Level: 17 to 18 yrs. Old English Level: English IV and Honors English IV Sources “The Ballad.” Grinnell College. Erik Simpson. 18 September 2011. Web. “Early Child Ballads.” PBM. Greg Lindahl. 18 September 2011. Web. Prentice Hall Literature: The British Tradition. Penguin Edition. 1 vol. New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc, 2007. Print. Rationale The NCSCoS requires that we explore British literature, and medieval ballads were an important part of the evolution of British literature. Also, studying ballads gives us, as readers, insight into the lives of those living in the medieval time period much like studying music from our own culture gives us insight into the workings of our own society. Focus & Review Journal: One hundred years from now a historian is given songs from today to analyze and learn how we lived as a society. What kinds of songs would they look at? What assumptions do you think the historian would make about our society? Do you think that the songs would give them a good idea of what life is like today? Objectives Students will understand the history and composition of ballads and how they relate to medieval history. NCSCoS Standards 1.02 Respond to texts so that the audience will: make connections between the learner's life and the text reflect on how cultural or historical perspectives may have influenced these responses 2.02 Analyze general principles at work in life and literature by: discovering and defining principles at work in personal experience and in literature. -

Resisting Radical Energies:Walter Scott's Minstrelsy of the Scottish

Cycnos 18/06/2014 10:38 Cycnos | Volume 19 n°1 Résistances - Susan OLIVER : Resisting Radical Energies:Walter Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Borderand the Re-Fashioning of the Border Ballads Texte intégral Walter Scott conceived of and began his first major publication, the Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, in the early 1790s. Throughout that decade and into the first three years of the nineteenth century, he worked consistently at accumulating the substantial range of ballad versions and archival material that he would use to produce what was intended to be an authoritative and definitive print version of oral and traditional Borders ballad culture. For the remainder of his life Scott continued to write and speak with affection of his “Liddesdale Raids,” the ballad collecting and research trips that he made into the Borders country around Liddesdale mainly during the years 1792–99. J. G. Lockhart, his son-in-law and biographer, describes the period spent compiling the Minstrelsy as “a labour of love truly, if ever there was,” noting that the degree of devotion was such that the project formed “the editor’s chief occupation” during the years 1800 and 1801. 1 At the same time, Lockhart takes particular care to state that the ballad project did not prevent Scott from attending the Bar in Edinburgh or from fulfilling his responsibilities as Sheriff Depute of Selkirkshire, a post he was appointed to on 16th December 1799. 2 The initial two volumes of the Minstrelsy, respectively sub-titled “Historical Ballads” and “Romantic Ballads,” were published in January 1802. 3 A third volume, supplementary to the first two, was published in May 1803. -

English 577.02 Folklore 2: the Traditional Ballad (Tu/Th 9:35AM - 10:55AM; Hopkins Hall 246)

English 577.02 Folklore 2: The Traditional Ballad (Tu/Th 9:35AM - 10:55AM; Hopkins Hall 246) Instructor: Richard F. Green ([email protected]; phone: 292-6065) Office Hours: Wednesday 11:30 - 2:30 (Denney 529) Text: English and Scottish Popular Ballads, ed. F.J. Child, 5 vols (Cambridge, Mass.: 1882- 1898); available online at http://www.bluegrassmessengers.com/the-305-child-ballads.aspx.\ August Thurs 22 Introduction: “What is a Ballad?” Sources Tues 27 Introduction: Ballad Terminology: “The Gypsy Laddie” (Child 200) Thurs 29 “From Sir Eglamour of Artois to Old Bangum” (Child 18) September Tues 3 Movie: The Songcatcher Pt 1 Thurs 5 Movie: The Songcatcher Pt 2 Tues 10 Tragic Ballads Thurs 12 Twa Sisters (Child 10) Tues 17 Lord Thomas and Fair Annet (Child 73) Thurs 19 Romantic Ballads Tues 24 Young Bateman (Child 53) October Tues 1 Fair Annie (Child 62) Thurs 3 Supernatural Ballads Tues 8 Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight (Child 4) Thurs 10 Wife of Usher’s Well (Child 79) Tues 15 Religious Ballads Thurs 17 Cherry Tree Carol (Child 54) Tues 22 Bitter Withy Thurs 24 Historical & Border Ballads Tues 29 Sir Patrick Spens (Child 58) Thurs 31 Mary Hamilton (Child 173) November Tues 5 Outlaw & Pirate Ballads Thurs 7 Geordie (Child 209) Tues 12 Henry Martin (Child 250) Thurs 14 Humorous Ballads Tues 19 Our Goodman (Child 274) Thurs 21 The Farmer’s Curst Wife (Child 278) S6, S7, S8, S9, S23, S24) Tues 24 American Ballads Thurs 26 Stagolee, Jesse James, John Hardy Tues 28 Thanksgiving (PAPERS DUE) Jones, Omie Wise, Pretty Polly, &c. -

Learning Lineage and the Problem of Authenticity in Ozark Folk Music

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1-1-2020 Learning Lineage And The Problem Of Authenticity In Ozark Folk Music Kevin Lyle Tharp Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Recommended Citation Tharp, Kevin Lyle, "Learning Lineage And The Problem Of Authenticity In Ozark Folk Music" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1829. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1829 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LEARNING LINEAGE AND THE PROBLEM OF AUTHENTICITY IN OZARK FOLK MUSIC A Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music The University of Mississippi by KEVIN L. THARP May 2020 Copyright Kevin L. Tharp 2020 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Thorough examination of the existing research and the content of ballad and folk song collections reveals a lack of information regarding the methods by which folk musicians learn the music they perform. The centuries-old practice of folk song and ballad performance is well- documented. Many Child ballads and other folk songs have been passed down through the generations. Oral tradition is the principal method of transmission in Ozark folk music. The variants this method produces are considered evidence of authenticity. Although alteration is a distinguishing characteristic of songs passed down in the oral tradition, many ballad variants have persisted in the folk record for great lengths of time without being altered beyond recognition. -

A BOOK of OLD BALLADS Selected and with an Introduction

A BOOK OF OLD BALLADS Selected and with an Introduction by BEVERLEY NICHOLS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The thanks and acknowledgments of the publishers are due to the following: to Messrs. B. Feldman & Co., 125 Shaftesbury Avenue, W.C. 2, for "It's a Long Way to Tipperary"; to Mr. Rudyard Kipling and Messrs. Methuen & Co. for "Mandalay" from _Barrack Room Ballads_; and to the Executors of the late Oscar Wilde for "The Ballad of Reading Gaol." "The Earl of Mar's Daughter", "The Wife of Usher's Well", "The Three Ravens", "Thomas the Rhymer", "Clerk Colvill", "Young Beichen", "May Collin", and "Hynd Horn" have been reprinted from _English and Scottish Ballads_, edited by Mr. G. L. Kittredge and the late Mr. F. J. Child, and published by the Houghton Mifflin Company. The remainder of the ballads in this book, with the exception of "John Brown's Body", are from _Percy's Reliques_, Volumes I and II. CONTENTS FOREWORD MANDALAY THE FROLICKSOME DUKE THE KNIGHT AND SHEPHERD'S DAUGHTER KING ESTMERE KING JOHN AND THE ABBOT OF CANTERBURY BARBARA ALLEN'S CRUELTY FAIR ROSAMOND ROBIN HOOD AND GUY OF GISBORNE THE BOY AND THE MANTLE THE HEIR OF LINNE KING COPHETUA AND THE BEGGAR MAID SIR ANDREW BARTON MAY COLLIN THE BLIND BEGGAR'S DAUGHTER OF BEDNALL GREEN THOMAS THE RHYMER YOUNG BEICHAN BRAVE LORD WILLOUGHBEY THE SPANISH LADY'S LOVE THE FRIAR OF ORDERS GRAY CLERK COLVILL SIR ALDINGAR EDOM O' GORDON CHEVY CHACE SIR LANCELOT DU LAKE GIL MORRICE THE CHILD OF ELLE CHILD WATERS KING EDWARD IV AND THE TANNER OF TAMWORTH SIR PATRICK SPENS THE EARL OF MAR'S DAUGHTER EDWARD, -

The Creighton-Senior Collaboration, 1932-51

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Athabasca University Library Institutional Repository The Creighton-Senior Collaboration, 1932-51 The arrival of Doreen Senior in Halifax in the book, and she was looking for a new collaborator summer of 1932 was a fortuitous event for Canadian who could note the melodies while she wrote down folksong collecting. Doreen, a friend and disciple of the words. In her autobiography, A Life in Folklore, Maud Karpeles, was a folk and country dance she recalled her first meeting with Doreen in the instructor, trained by the English Folk Dance Society, following terms: who anticipated a career as a music teacher making good use of Cecil Sharp's published collections of For years the Nova Scotia Summer School had Folk Songs for Schools. She was aware that Maud been bringing interesting people here, and one day I was invited to meet a new teacher, Miss had recently undertaken two successful collecting Doreen Senior of the English Folk Song and trips to Newfoundland (in 1929 and 1930), and was Dance Society. She liked people and they liked curious to see if Nova Scotia might similarly afford her to such an extent that whenever I met one of interesting variants of old English folksongs and her old summer school students in later years, ballads, or even songs that had crossed the Atlantic they would always ask about her. She was a and subsequently disappeared in their more urban and musician with the gift of perfect pitch and she industrialized land of origin. -

English Ballads and Turkish Turkus a Comparative Study

British Journal of Arts and Social Sciences ISSN: 2046-9578, Vol.11 No.I (2012) ©BritishJournal Publishing, Inc. 2012 http://www.bjournal.co.uk/BJASS.aspx English Ballads and Turkish Turkus a Comparative Study Elmas Sahin Assist. Prof. Elmas Sahin, Cag University, The Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Turkey, [email protected], Tel: +90 324 651 48 00, fax: +90 324 651 48 11 Abstract Although "ballad" whose origins based on the medieval period in the Western World; derived from Latin, and Italian word 'ballata' (ballare :/ = dance) to “turku” occurring approximately in the same centuries in the Eastern World, whose sources of the'' Turkish'' word sung by melodies in spoken tradition of Anatolia, a term given for folk poetry /songs "Turks" emerged in different nations and different cultures appear in similar directions. When both Ballads and folk songs as products of different cultures in terms of topics, motifs, structures and forms were analyzed are similar in many respects despite of exceptions. Here we will handle and evaluate the ballads and turkus, folk songs, being the products of different countries and cultures, according to the Comparative Literature and Criticism, and its theory by focusing the selected works, by means of a pluralistic approach. In this context these two literary genres having literary values, similar and different aspects in structure and content will be evaluated compared and contrasted in light of various methods as formal ,structural, reception and historical approaches. Keywords: ballad, turku, folk songs, folk poems, comparative literature 33 British Journal of Arts and Social Sciences ISSN: 2046-9578, Introduction Although both Ballad and Türkü are the products of different countries and cultures, except for some unimportant differences, they have similar aspects in terms of their subject, theme, motive, structure and form.