Observing Protest from a Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artists' Palettes

TECHNICAL ART HISTORY COLLOQUIUM Artists’ Palettes Images: details from Catharina van Hemessen, Self-portrait, c. 1527-28, Kunstmuseum Basel Cornelis Norbertus Gijsbrechts, A cabinet in the artist’s studio, 1670-71, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen Willem van Mieris, Self-portrait, c. 1705, Lakenhal, Leiden Date & Time: Thursday 12 March 2020 – 14:00-15:45 Location: Room B, Ateliergebouw, Hobbemastraat 22, Amsterdam Presentations: Céline Talon / Dr. Gianluca Pastorelli / Carol Pottasch Chair: Dr. Abbie Vandivere, University of Amsterdam / Mauritshuis Registration: Please send an email to [email protected] before 5 March The Technical Art History Colloquia are organised by Sven Dupré (Utrecht University and University of Amsterdam, PI ERC ARTECHNE), Arjan de Koomen (University of Amsterdam, Coordinator MA Technical Art History), Abbie Vandivere (University of Amsterdam, Coordinator MA Technical Art History & Paintings Conservator, Mauritshuis, The Hague), Erma Hermens (University of Amsterdam and Rijksmuseum) and Ann-Sophie Lehmann (University of Groningen). The Technical Art History Colloquia are a cooperation of the ARTECHNE Project (Utrecht University and University of Amsterdam), the Netherlands Institute for Conservation, Art and Science (NICAS), the University of Amsterdam and the Mauritshuis. The ARTECHNE project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 648718). Palettes and colour mixtures in Northern Renaissance painting technique Celine Talon, Paintings Conservator and Art Historian, Brussels Celine Talon will present the framework for her ongoing research into the palettes of Northern painters, as depicted in paintings and illuminations. The aspects she considers include their shape and size, as well as the variety of colours represented on them. -

Self-Portrait C

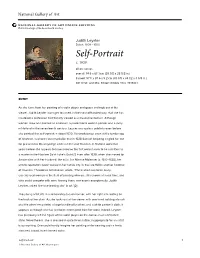

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Judith Leyster Dutch, 1609 - 1660 Self-Portrait c. 1630 oil on canvas overall: 74.6 x 65.1 cm (29 3/8 x 25 5/8 in.) framed: 97.5 x 87.6 x 9.2 cm (38 3/8 x 34 1/2 x 3 5/8 in.) Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss 1949.6.1 ENTRY As she turns from her painting of a violin player and gazes smilingly out at the viewer, Judith Leyster manages to assert, in the most offhanded way, that she has mastered a profession traditionally viewed as a masculine domain. Although women drew and painted as amateurs, a professional woman painter was a rarity in Holland in the seventeenth century. Leyster was quite a celebrity even before she painted this self-portrait in about 1630. Her proficiency, even at the tender age of nineteen, had been so remarkable that in 1628 Samuel Ampzing singled her out for praise in his Beschryvinge ende lof der stad Haerlem in Holland some five years before she appears to have become the first woman ever to be admitted as a master in the Haarlem Saint Luke’s Guild. [1] Even after 1636, when she moved to Amsterdam with her husband, the artist Jan Miense Molenaer (c. 1610–1668), her artistic reputation never waned in her native city. In the late 1640s another historian of Haarlem, Theodorus Schrevelius, wrote, “There also have been many experienced women in the field of painting who are still renowned in our time, and who could compete with men. -

Sign of the Times a Concise History of the Signature in Netherlandish Painting 1432-1575

SIGN OF THE TIMES A CONCISE HISTORY OF THE SIGNATURE IN NETHERLANDISH PAINTING 1432-1575 [Rue] [Date et Heure] Ruben Suykerbuyk Research Master’s Thesis 2012-2013 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. P.A. Hecht Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context Utrecht University – Faculty of Humanities (xxx)yyy-yyyy “Wenn eine Wissenschaft so umfassend, wie die Kunstgeschichte es tut und tun muß, von Hypothesen jeden Grades Gebrauch macht, so tut sie gut daran, die Fundamente des von ihr errichteten Gebäudes immer aufs neue auf ihre Tragfähigkeit zu prüfen. Im folgenden will ich an einigen Stellen mit dem Hammer anklopfen.” Dehio 1910, p. 55 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME I I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. PROLOGUE 9 III. DEVELOPMENTS IN ANTWERP 19 Some enigmatic letters 22 The earliest signatures 28 Gossart’s ‘humanistic’ signature 31 Increasing numbers 36 Proverbial exceptions 52 A practice spreads 54 IV. EPILOGUE 59 V. CONCLUSION 63 VI. BIBLIOGRAPHY 66 VOLUME II I. IMAGES II. APPENDICES Appendix I – Timeline Appendix II – Signatures Marinus van Reymerswale Appendix III – Authentication of a painting by Frans Floris (1576) Appendix IV – Signatures Michiel Coxcie I. INTRODUCTION 1 Investigating signatures touches upon the real core of art history: connoisseurship. The construction of oeuvres is one of the basic tasks of art historians. Besides documents, they therefore inevitably have to make use of signatures. However, several great connoisseurs – Berenson, Friedländer – emphasize that signatures are faked quite often. Consequently, an investigation of signature practices can easily be criticized for the mere fact that it is very difficult to be sure of the authenticity of all the studied signatures. -

Self-Portrait C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Judith Leyster Dutch, 1609 - 1660 Self-Portrait c. 1630 oil on canvas overall: 74.6 x 65.1 cm (29 3/8 x 25 5/8 in.) framed: 97.5 x 87.6 x 9.2 cm (38 3/8 x 34 1/2 x 3 5/8 in.) Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss 1949.6.1 ENTRY As she turns from her painting of a violin player and gazes smilingly out at the viewer, Judith Leyster manages to assert, in the most offhanded way, that she has mastered a profession traditionally viewed as a masculine domain. Although women drew and painted as amateurs, a professional woman painter was a rarity in Holland in the seventeenth century. Leyster was quite a celebrity even before she painted this self-portrait in about 1630. Her proficiency, even at the tender age of nineteen, had been so remarkable that in 1628 Samuel Ampzing singled her out for praise in his Beschryvinge ende lof der stad Haerlem in Holland some five years before she appears to have become the first woman ever to be admitted as a master in the Haarlem Saint Luke’s Guild.[1] Even after 1636, when she moved to Amsterdam with her husband, the artist Jan Miense Molenaer (c. 1610–1668), her artistic reputation never waned in her native city. In the late 1640s another historian of Haarlem, Theodorus Schrevelius, wrote, “There also have been many experienced women in the field of painting who are still renowned in our time, and who could compete with men. -

The Education of Women Artists in Northern Europe, 1500-1750

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar Student Research Submissions Spring 5-3-2019 The Education of Women Artists in Northern Europe, 1500-1750 Elayna Gladstone Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research Part of the German Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gladstone, Elayna, "The Education of Women Artists in Northern Europe, 1500-1750" (2019). Student Research Submissions. 274. https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research/274 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Submissions by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Die meisten Kuenstler aus der Renaissance und aus dem Barock, an die man sich heute erinnert, sind Maenner, und man hat viele schriftliche Berichte von ihrer Bildung. Viele Leute denken an maennliche Kuenstler, wenn historische Kunst erwaehnt wird, aber das bedeutet nicht, dass weibliche Kuenstlerinnen nicht existiert haben; es gab weniger, und Kuenstlerinnen mussten kämpfen, um an der Welt der Kunst teilzunehmen. Trotzdem konnten manche Frauen erfolgreich als Kuenstlerinnen sein, wenn sie genug Ausbildung und Privileg hatten. Catharina van Hemessen (1528-1580) und Adriaen Isenbrandt (gt. 1551) sind zwei flaemische Kuenstler der Renaissance, die Zeitgenossen waren. Beide Kuenstler arbeiteten mit Oelgemaelden und Platten oder Holz, weil diese die Medien der Wahl in Flandern statt Skulpturen oder Wandbilder1 waren. Beide Kuenstler waren Lehrlinge von Meisterkuenstlern. Ihre Werke waren von einer Anzahl von koeniglichen Hoefen ueberall in Europa sehr begehrt. Isenbrandt und van Hemessen hatten aenliche berufliche Geschichten, und sie waehlten auch aenliche Themen zu mahlen. -

Self-Portrait Guild of Saint Luke, the First Woman Admitted for Which an Oeuvre Can Be Cited, and in 1635 She Is C

show her to have been one of his closest and most Bibliography successful followers. Furthermore, other compari Ampzing 1628: 370. Schrevelius 1648: 290. sons suggest that she was also influenced by the Harms 1927. work of his brother, Dirck Hals (i 591 -1656). Should Hofrichter 1975. Leyster have been in either of their studios, it would Philadelphia 1984: 233-235. seem that she would have been there prior to 1629, Hofrichter 1989. Brown/MacLaren 1992: 226. the year she starts to sign and date her paintings, and Haarlem 1993. probably before 1628, when Ampzing implies that she was working as an independent artist. In the years following her return to Haarlem, Judith Leyster achieved a degree of professional suc 1949.6.1 (1050) cess that was quite remarkable for a woman of her time. By 1633 she was a member of the Haarlem Self-Portrait Guild of Saint Luke, the first woman admitted for which an oeuvre can be cited, and in 1635 she is c. 1630 Oil on canvas, 72.3 x 65.3 (29*6 x 25^) recorded as having three students. One of these, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss Willem Woutersz., subsequently defected to the studio of Hals, presumably without adequate warn Technical Notes: The support, a plain-woven fabric with ing, for Leyster went before the Guild of Saint Luke numerous slubs and weave imperfections, has been lined with the tacking margins trimmed. A large horizontal rec in October 1635 to make a (successful) demand for tangle of original canvas is missing from the bottom left in an payment from Woutersz.'s mother. -

Download?Doi=10.1.1.405.2460&Rep=Rep1&Type=Pdf (Accessed July 5, 2020) and Expanded in Wayne M

VENTI journal Air — Experience — Aesthetics venti-journal.com AIR BUBBLES Bubbles in Northern European Self-Portraits: Homo bulla est Liana Cheney | essay | 88 Volume One, Issue Two Fall 2020 Charles Henry Bennett and William Harry Rogers, Psalm CXIX. 37. Turn Away Mine Eyes From Beholding Vanity, 1861 engraving. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Looking at this engraving from 1861, a small figure of a court jester stands within a round frame surrounded by nat- ural decoration. Representing Psalm CXIX, “Turn away mine eyes from beholding vanity,” it declares as the young boy seems besotted with the floating orbs surrounding him. Perhaps he is caught up in a reflection of himself. Perhaps he is entranced by how the bubbles reflect the light around him. Liana Cheney examines a similar duality in a pair of Northern European self-portraits in her essay “Bubbles in Northern European Self-Portraiture: Homo est bulla est (The Individual is a Bubble).” The paintings by Clara Peeters and David Bailly mix the genres of self-portrait and still life, pairing the artists with various ephemera. With emblems of this period as a lens for these self-portraits with vanitas, Cheney examines the pictorial bubbles in these self-portraits for their multiplicity of meanings: refractors of lights; harbingers of the transitory nature of life; and reflections through which the artists can see themselves. Through examining the items on display and the bubbles that float above the scene, the artists relate attributes of their own, showing off their skill and thus their vanity. - The Editors BUBBLES IN NORTHERN EUROPEAN SELF-PORTRAITS: HOMO BULLA EST (THE INDIVIDUAL AS A BUBBLE) Liana De Girolami Cheney Northern European depictions of Homo bulla est (The Individual is a Bubble) derived from two emblematic and literary sources: one classical and one sixteenth century. -

![[In]Visible: Paintings by Women Artists in the National Gallery, London: An](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1586/in-visible-paintings-by-women-artists-in-the-national-gallery-london-an-10441586.webp)

[In]Visible: Paintings by Women Artists in the National Gallery, London: An

[In]Visible: Paintings by Women Artists in the National Gallery, London: An Interview with Letizia Treves and Francesca Whitlum-Cooper Susanna Avery-Quash, Letizia Treves, and Francesca Whitlum-Cooper The National Gallery’s recent acquisition of Artemisia Gentileschi’s Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria (Fig. 1) takes the number of works by female artists in the permanent collection to twenty-one.1 Artists repre- sented at the National Gallery include Henriette Browne, Berthe Morisot, Rachel Ruysch, Rosa Bonheur, Catharina van Hemessen, Elisabeth Louise Fig. 1: Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1615–17, oil on canvas, 71.4 × 69 cm. © National Gallery, London. 1 For more on Artemisia Gentileschi’s Self-Portrait, see <https://www.nationalgallery. org.uk/paintings/artemisia-gentileschi-self-portrait-as-saint-catherine-of-alexan- dria>; and <https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/rare-self-portrait-by-ar- temisia-gentileschi-now-on-display>. For videos about the painting’s conservation, see <https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLvb2y26xK6Y6F2GH6yosrsgGcCm gaNNjp>; they are also accessible via the painting’s page and special feature on the gallery’s website noted above [all accessed 4 March 2019]. 2 Vigée-Lebrun, Judith Leyster, Rosalba Carriera, Marie Blancour, Vivien Blackett, Madeleine Strindberg, Maggi Hambling, and Paula Rego. In this interview at the National Gallery, Susanna Avery-Quash (Senior Research Curator in the History of Collecting) asks Letizia Treves (The James and Sarah Sassoon Curator of Later Italian, Spanish, and French 17th-Century Paintings) and Francesca Whitlum-Cooper (The Myojin-Nadar Associate Curator of Paintings 1600–1800) about the expe- riences of women artists in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and how their work was received during their lifetimes and later. -

Catharina Van Hemessen (1528 - Na 1567)

Karolien De Clippel: Catharina van Hemessen (1528 - na 1567). Een monografische studie over een 'uytnemende wel geschickte vrouwe in de conste der schilderyen' (= Verhandelingen van de Koninklijke Vlaamse Academie van België voor Wetenschapen en Kunsten. Nieuwe reeks; nr. 11), Brussel: Koninklijke Vlaamse Academie van België voor Wetenschapen en Kunsten 2004, 183 S., 79 Abb., ISBN 90-6569-921-x, EUR 40,00 Rezensiert von: Ann Jensen Adams University of California at Santa Barbara Only thirteen signed works survive - nine portraits and four religious paintings - from the hand of the sixteenth-century artist whom, in his description of the Lowlands published in 1567, Ludovico Guicciardini called one of the "outstanding women in this art [of painting] who is still alive.". The following year Giorgio Vasari mentioned her, and her name remained in circulation a century later when in 1643 Johan van Beverwijck included her in his Van de Uitnementheyt des vrouwelicken geslachts (On the excellence of the female sex). After four and one-half centuries of being relegated to a few lines or at most a few pages in texts on other artists or subjects, 2004 witnessed the appearance of not one but two monographs on the Flemish artist Catharina van Hemessen (c. 1528 - after 1567). [1] In the exemplary monograph here under review, Karolien De Clippel divides her study into three chapters: The first two cover Catharina van Hemessen's life and work. The third chapter tracks a critical history of the artist and, in the process, provides a superb overview of the rhetoric and reality of the female artist in both art theory and in cultural practices. -

Copyright by Alexis Diane Slater 2019

Copyright by Alexis Diane Slater 2019 The Thesis Committee for Alexis Diane Slater Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Thesis: Mayken Verhulst: A Professional Woman Painter and Print Publisher in the Sixteenth-Century Low Countries APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Jeffrey Chipps Smith, Supervisor Joan A. Holladay Mayken Verhulst: A Professional Woman Painter and Print Publisher in the Sixteenth-Century Low Countries by Alexis Diane Slater Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank Dr. Jeffrey Chipps Smith for his positivity and support throughout not only this project, but for the duration of my master’s degree as well. Under your guidance, I know that I have grown exponentially as a scholar, and I cannot thank you enough. Thank you also to my second reader, Dr. Joan A. Holladay, whose attention to detail and generosity of time and effort I have greatly valued. To Sarah Farkas and Arianna Ray—having you two by my side to bemoan the struggles of graduate school and to delight over the oddities of the medieval and early modern world has been fantastic. I will miss you all as we go our separate ways. To my family—Mom, Dad, and JJ—thank you for your ceaseless encouragement from kindergarten until today. Knowing that you believe in what I am doing means the world to me. Many thanks also to Dr. -

Sofonisba Anguissola and Her Early Teachers

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Fall 1-5-2018 SOFONISBA ANGUISSOLA AND HER EARLY TEACHERS Lily Chin CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/276 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SOFONISBA ANGUISSOLA AND HER EARLY TEACHERS by Lily Chin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2017 Thesis Sponsor: December 18, 2017 Maria H. Loh Date Signature December 18, 2017 Nebahat Avcioglu Date Signature of Second Reader Copyright © 2017 by Lily Chin. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ii List of Illustrations iii Introduction 1 Chapter One: Beginnings 12 Chapter Two: The Birth of an Artist and Foundational Work 22 Chapter Three: The Emergence and Evolution of an Artist 41 Chapter Four: The Artist Forges Her Own Path 52 Conclusion: Anguissola’s Legacy 64 Bibliography 68 Illustrations 75 i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Working on this thesis has been a long journey for me. I wish to thank my advisor, Professor Loh, for helping me complete this journey. She is incredibly knowledgeable and supportive. I am grateful for the time that she spent with me on my thesis and for her suggestions. I truly feel lucky to have worked with her and to have her guidance and insight. -

April 2006 Journal

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 23, No. 1 www.hnanews.org April 2006 A New Acquisition for the Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp Cornelis De Vos, Portrait of Jan Vekemans (c. 1625) about to be reunited with the portraits of his parents, Joris Vekemans and Maria van Ghinderdeuren, his brother Frans and one of his sisters. Photo: Michel Ceuterick HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 1, April 2006 1 From the President HNA News With spring upon us – unless, of course, you live in Syracuse – HNA Conference, Washington-Baltimore there is much to look forward to as the year unfolds, not in the least of which will be our sixth fourth quadrennial conference. But before I November 8-12, 2006 discuss the latest news germane to Historians of Netherlandish Art, I This is the last Newsletter before the HNA conference. The would first like to thank Anne Lowenthal for having organized such a preliminary program, workshop sign-up sheet, registration and hotel stimulating series of lectures on the life and work of the eminent information will be posted on the website as well as sent out as scholar, Julius Held, which was our organization’s official session at hardcopy to all members in May. For further information, please the recent Annual Meeting of the College Art Association in Boston. contact the conference organizers Aneta Georgievska-Shine, It was good to see so many of you in attendance there, as well as at [email protected], and Quint Gregory, [email protected].