Judith Leyster: a Study of Extraordinary Expression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art from the Ancient Mediterranean and Europe Before 1850 Gallery 15

Art from the Ancient Mediterranean and Europe before 1850 Gallery 15 QUESTIONS? Contact us at [email protected] ACKLAND ART MUSEUM The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 101 S. Columbia Street Chapel Hill, NC 27514 Phone: 919-966-5736 MUSEUM HOURS Wed - Sat 10 a.m. - 5 p.m. Sun 1 - 5 p.m. Closed Mondays & Tuesdays. Closed July 4th, Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, & New Year’s Day. 1 Domenichino Italian, 1581 – 1641 Landscape with Fishermen, Hunters, and Washerwomen, c. 1604 oil on canvas Ackland Fund, 66.18.1 About the Art • Italian art criticism of this period describes the concept of “variety,” in which paintings include multiple kinds of everything. Here we see people of all ages, nude and clothed, performing varied activities in numerous poses, all in a setting that includes different bodies of water, types of architecture, land forms, and animals. • Wealthy Roman patrons liked landscapes like this one, combining natural and human-made elements in an orderly structure. Rather than emphasizing the vast distance between foreground and horizon with a sweeping view, Domenichino placed boundaries between the foreground (the shoreline), middle ground (architecture), and distance. Viewers can then experience the scene’s depth in a more measured way. • For many years, scholars thought this was a copy of a painting by Domenichino, but recently it has been argued that it is an original. The argument is based on careful comparison of many of the picture’s stylistic characteristics, and on the presence of so many figures in complex poses. At this point in Domenichino’s career he wanted more commissions for narrative scenes and knew he needed to demonstrate his skill in depicting human action. -

Sztuki Piękne)

Sebastian Borowicz Rozdział VII W stronę realizmu – wiek XVII (sztuki piękne) „Nikt bardziej nie upodabnia się do szaleńca niż pijany”1079. „Mistrzami malarstwa są ci, którzy najbardziej zbliżają się do życia”1080. Wizualna sekcja starości Wiek XVII to czas rozkwitu nowej, realistycznej sztuki, opartej już nie tyle na perspektywie albertiańskiej, ile kepleriańskiej1081; to również okres malarskiej „sekcji” starości. Nigdy wcześniej i nigdy później w historii europejskiego malarstwa, wyobrażenia starych kobiet nie były tak liczne i tak różnicowane: od portretu realistycznego1082 1079 „NIL. SIMILIVS. INSANO. QVAM. EBRIVS” – inskrypcja umieszczona na kartuszu, w górnej części obrazu Jacoba Jordaensa Król pije, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wiedeń. 1080 Gerbrand Bredero (1585–1618), poeta niderlandzki. Cyt. za: W. Łysiak, Malarstwo białego człowieka, t. 4, Warszawa 2010, s. 353 (tłum. nieco zmienione). 1081 S. Alpers, The Art of Describing – Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, Chicago 1993; J. Friday, Photography and the Representation of Vision, „The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism” 59:4 (2001), s. 351–362. 1082 Np. barokowy portret trumienny. Zob. także: Rembrandt, Modląca się staruszka lub Matka malarza (1630), Residenzgalerie, Salzburg; Abraham Bloemaert, Głowa starej kobiety (1632), kolekcja prywatna; Michiel Sweerts, Głowa starej kobiety (1654), J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Monogramista IS, Stara kobieta (1651), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wiedeń. 314 Sebastian Borowicz po wyobrażenia alegoryczne1083, postacie biblijne1084, mitologiczne1085 czy sceny rodzajowe1086; od obrazów o charakterze historycznodokumentacyjnym po wyobrażenia należące do sfery historii idei1087, wpisujące się zarówno w pozy tywne1088, jak i negatywne klisze kulturowe; począwszy od Prorokini Anny Rembrandta, przez portrety ubogich staruszek1089, nobliwe portrety zamoż nych, starych kobiet1090, obrazy kobiet zanurzonych w lekturze filozoficznej1091 1083 Bernardo Strozzi, Stara kobieta przed lustrem lub Stara zalotnica (1615), Музей изобразительных искусств им. -

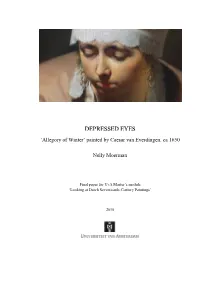

Depressed Eyes

D E P R E S S E D E Y E S ‘ Allegory of Winter’ painted by Caesar van Everdingen, c a 1 6 5 0 Nelly Moerman Final paper for UvA Master’s module ‘Looking at Dutch Seventeenth - Century Paintings’ 2010 D EPRESSED EYES || Nelly Moerman - 2 CONTENTS page 1. Introduction 3 2. ‘Allegory o f Winter’ by Caesar van Everdingen, c. 1650 3 3. ‘Principael’ or copy 5 4. Caesar van Everdingen (1616/17 - 1678), his life and work 7 5. Allegorical representations of winter 10 6. What is the meaning of the painting? 11 7. ‘Covering’ in a psychological se nse 12 8. Look - alike of Lady Winter 12 9. Arguments for the grief and sorrow theory 14 10. The Venus and Adonis paintings 15 11. Chronological order 16 12. Conclusion 17 13. Summary 17 Appendix I Bibliography 18 Appendix II List of illustrations 20 A ppen dix III Illustrations 22 Note: With thanks to the photographic services of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam for supplying a digital reproduction. Professional translation assistance was given by Janey Tucker (Diesse, CH). ISBN/EAN: 978 - 90 - 805290 - 6 - 9 © Copyright N. Moerman 2010 Information: Nelly Moerman Doude van Troostwijkstraat 54 1391 ET Abcoude The Netherlands E - mail: [email protected] D EPRESSED EYES || Nelly Moerman - 3 1. Introduction When visiting the Rijksmuseum, it seems that all that tourists w ant to see is Rembrandt’s ‘ Night W atch ’. However, before arriving at the right spot, they pass a painting which makes nearly everybody stop and look. What attracts their attention is a beautiful but mysterious lady with her eyes cast down. -

Gabriel Metsu (Leiden 1629 – 1667 Amsterdam)

Gabriel Metsu (Leiden 1629 – 1667 Amsterdam) How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Gabriel Metsu” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/gabriel- metsu/ (accessed September 28, 2021). A PDF of every version of this biography is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Gabriel Metsu Page 2 of 5 Gabriel Metsu was born sometime in late 1629. His parents were the painter Jacques Metsu (ca. 1588–1629) and the midwife Jacquemijn Garniers (ca. 1590–1651).[1] Before settling in Leiden around 1615, Metsu’s father spent some time in Gouda, earning his living as a painter of patterns for tapestry manufacturers. No work by Jacques is known, nor do paintings attributed to him appear in Leiden inventories.[2] Both of Metsu’s parents came from Southwest Flanders, but when they were still children their families moved to the Dutch Republic. When the couple wed in Leiden in 1625, neither was young and both had previously been married. Jacquemijn’s second husband, Guilliam Fermout (d. ca. 1624) from Dordrecht, had also been a painter. Jacques Metsu never knew his son, for he died eight months before Metsu was born.[3] In 1636 his widow took a fourth husband, Cornelis Bontecraey (d. 1649), an inland water skipper with sufficient means to provide well for Metsu, as well as for his half-brother and two half-sisters—all three from Jacquemijn’s first marriage. -

Studienraum Study A

B i o - B i BL i o g R a F i s c H e s L e x i Ko n B i o g R a PH i c a L a n d B i BL i o g R a PH i c a L L e x i c o n Kurt Badt concentration camp in Dachau in 1933. Dismissed Paul Frankl Nach künstlerischem Studium an den Kunstge- des Zweiten Weltkrieges 15-monatige Internierung Ruth Kraemer, geb. schweisheimer in 1971 and worked at the Bibliotheca Hertziana Studied art history in Berlin, Heidelberg, Munich, at the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin until 1935. Dis- VERÖFFENTLICHUNGEN \ PUBLICATIONS: Museen, 1932 Habilitation bei Pinder. 1933 Ent- Studied art history from 1918–1921 in Munich after geb. 03.03.1890 in Berlin, from the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum in 1935 by b. 01/02/1878 in Prague; werbeschulen in München und Halle 1928–1933 unter dem Vichy-Regime. 1964 verstarb Heinemann geb. 27.08.1908 in München, in Rome. Received the honorary citizenship of the and Leipzig. Gained doctorate in 1924 under Pinder. missed in 1935 by the National Socialist authorities. Augustin Hirschvogel. Ein Meister der Deutschen lassung als Privatdozent durch die nationalsozia- active service in World War I. Gained doctorate in gest. 22.11.1973 in Überlingen am Bodensee the National Socialist authorities. Emigrated to the d. 04/22/1962 in Princeton, NJ (USA) Studium der Kunstgeschichte in München. 1933 über den sich seit 1957 hinziehenden Entschädi- gest. 27.09.2005 in New York, NY (USA) city of Rome shortly before his death. -

The Collecting, Dealing and Patronage Practices of Gaspare Roomer

ART AND BUSINESS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NAPLES: THE COLLECTING, DEALING AND PATRONAGE PRACTICES OF GASPARE ROOMER by Chantelle Lepine-Cercone A thesis submitted to the Department of Art History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (November, 2014) Copyright ©Chantelle Lepine-Cercone, 2014 Abstract This thesis examines the cultural influence of the seventeenth-century Flemish merchant Gaspare Roomer, who lived in Naples from 1616 until 1674. Specifically, it explores his art dealing, collecting and patronage activities, which exerted a notable influence on Neapolitan society. Using bank documents, letters, artist biographies and guidebooks, Roomer’s practices as an art dealer are studied and his importance as a major figure in the artistic exchange between Northern and Sourthern Europe is elucidated. His collection is primarily reconstructed using inventories, wills and artist biographies. Through this examination, Roomer emerges as one of Naples’ most prominent collectors of landscapes, still lifes and battle scenes, in addition to being a sophisticated collector of history paintings. The merchant’s relationship to the Spanish viceregal government of Naples is also discussed, as are his contributions to charity. Giving paintings to notable individuals and large donations to religious institutions were another way in which Roomer exacted influence. This study of Roomer’s cultural importance is comprehensive, exploring both Northern and Southern European sources. Through extensive use of primary source material, the full extent of Roomer’s art dealing, collecting and patronage practices are thoroughly examined. ii Acknowledgements I am deeply thankful to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Sebastian Schütze. -

20-A Richard Diebenkorn, Cityscape I, 1963

RICHARD DIEBENKORN [1922–1993] 20a Cityscape I, 1963 Although often derided by those who embraced the native ten- no human figure in this painting. But like it, Cityscape I compels dency toward realism, abstract painting was avidly pursued by us to think about man’s effect on the natural world. Diebenkorn artists after World War II. In the hands of talented painters such leaves us with an impression of a landscape that has been as Jackson Pollack, Robert Motherwell, and Richard Diebenkorn, civilized — but only in part. abstract art displayed a robust energy and creative dynamism Cityscape I’s large canvas has a composition organized by geo- that was equal to America’s emergence as the new major metric planes of colored rectangles and stripes. Colorful, boxy player on the international stage. Unlike the art produced under houses run along a strip of road that divides the two sides of the fascist or communist regimes, which tended to be ideological painting: a man-made environment to the left, and open, pre- and narrowly didactic, abstract art focused on art itself and the sumably undeveloped, land to the right. This road, which travels pleasure of its creation. Richard Diebenkorn was a painter who almost from the bottom of the picture to the top, should allow moved from abstraction to figurative painting and then back the viewer to scan the painting quickly, but Diebenkorn has used again. If his work has any theme it is the light and atmosphere some artistic devices to make the journey a reflective one. of the West Coast. -

November 2012 Newsletter

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 29, No. 2 November 2012 Jan and/or Hubert van Eyck, The Three Marys at the Tomb, c. 1425-1435. Oil on panel. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. In the exhibition “De weg naar Van Eyck,” Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, October 13, 2012 – February 10, 2013. HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey (2009–2013) Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny (2009–2013) Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Contents Board Members President's Message .............................................................. 1 Paul Crenshaw (2012-2016) HNA News ............................................................................1 Wayne Franits (2009-2013) Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Martha Hollander (2012-2016) Exhibitions ............................................................................ 3 Henry Luttikhuizen (2009 and 2010-2014) -

De Verandering Van Kleur in Het Oeuvre Van Abraham Bloemaert

De verandering van kleur in het oeuvre van Abraham Bloemaert Noëlle Schoonderwoerd Masterscriptie Kunstgeschiedenis Universiteit van Amsterdam Dr. E. Kolfin Contents Inleiding ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 1. De verandering van het kleurenpalet van de zestiende naar de zeventiende eeuw. ................................ 4 De dood van Niobe’s kinderen (1591) .................................................................................................... 5 Mercurius, Argos en Io (1592) ................................................................................................................. 6 Judith toont het hoofd van Holofernes aan het volk (1593) .................................................................. 6 Mozes slaat water uit de rots (1596) ......................................................................................................... 7 Jozef en zijn broers (1595-1600) ............................................................................................................... 8 De aanbidding van de herders (1612) ..................................................................................................... 9 Maria Magdalena (1619) ........................................................................................................................ 10 De Emmaüsgangers (1622) ................................................................................................................... -

Rolin Madonna" and the Late-Medieval Devotional Portrait Author(S): Laura D

Surrogate Selves: The "Rolin Madonna" and the Late-Medieval Devotional Portrait Author(s): Laura D. Gelfand and Walter S. Gibson Source: Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, Vol. 29, No. 3/4 (2002), pp. 119-138 Published by: Stichting voor Nederlandse Kunsthistorische Publicaties Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3780931 . Accessed: 17/09/2014 15:52 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Stichting voor Nederlandse Kunsthistorische Publicaties is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 146.201.208.22 on Wed, 17 Sep 2014 15:52:43 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions I 19 Surrogateselves: the Rolin Madonna and the late-medieval devotionalportrait* LauraD. Gel/andand Walter S. Gibson TheMadonna of Chancellor Rolin (fig. i), paintedby Jan vanEyck omitted in thefinal painting, for what reason van Eyckabout I435, has longattracted great interest, we can onlyspeculate.3 Hence, it has been generally notonly for its spellbinding realism and glowingcolor, supposedthat Rolin's pious demeanor, his prayer book, butalso for the chancellor's apparent temerity in having and his audiencewith the Queen of Heaven and her himselfdepicted as prominentlyas the Virginand Child representlittle more than an elaborateeffort at Child,kneeling in their presence unaccompanied by the self-promotiondesigned to counter the negative reputa- usualpatron saint. -

Artists' Palettes

TECHNICAL ART HISTORY COLLOQUIUM Artists’ Palettes Images: details from Catharina van Hemessen, Self-portrait, c. 1527-28, Kunstmuseum Basel Cornelis Norbertus Gijsbrechts, A cabinet in the artist’s studio, 1670-71, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen Willem van Mieris, Self-portrait, c. 1705, Lakenhal, Leiden Date & Time: Thursday 12 March 2020 – 14:00-15:45 Location: Room B, Ateliergebouw, Hobbemastraat 22, Amsterdam Presentations: Céline Talon / Dr. Gianluca Pastorelli / Carol Pottasch Chair: Dr. Abbie Vandivere, University of Amsterdam / Mauritshuis Registration: Please send an email to [email protected] before 5 March The Technical Art History Colloquia are organised by Sven Dupré (Utrecht University and University of Amsterdam, PI ERC ARTECHNE), Arjan de Koomen (University of Amsterdam, Coordinator MA Technical Art History), Abbie Vandivere (University of Amsterdam, Coordinator MA Technical Art History & Paintings Conservator, Mauritshuis, The Hague), Erma Hermens (University of Amsterdam and Rijksmuseum) and Ann-Sophie Lehmann (University of Groningen). The Technical Art History Colloquia are a cooperation of the ARTECHNE Project (Utrecht University and University of Amsterdam), the Netherlands Institute for Conservation, Art and Science (NICAS), the University of Amsterdam and the Mauritshuis. The ARTECHNE project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 648718). Palettes and colour mixtures in Northern Renaissance painting technique Celine Talon, Paintings Conservator and Art Historian, Brussels Celine Talon will present the framework for her ongoing research into the palettes of Northern painters, as depicted in paintings and illuminations. The aspects she considers include their shape and size, as well as the variety of colours represented on them. -

Jan Steen: the Drawing Lesson

Jan Steen THE DRAWING LESSON Jan Steen THE DRAWING LESSON John Walsh GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Los ANGELES For my teacher Julius S. Held in gratitude Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Jan Steen (Dutch, 1626-1679). The Drawing Lesson, circa 1665 (detail). Oil on panel, Mollie Holtman, Editor 49.3 x 41 cm. (i93/s x i6î/4 in.). Los Angeles, Stacy Miyagawa, Production Coordinator J. Paul Getty Museum (83.PB.388). Jeffrey Cohen, Designer Lou Meluso, Photographer Frontispiece: Jan Steen. Self-Portrait, circa 1665. © 1996 The J. Paul Getty Museum Oil on canvas, 73 x 62 cm (283/4 x 243/ in.). 17985 Pacific Coast Highway 8 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum (sK-A-383). Malibu, California 90265-5799 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs Mailing address: provided) courtesy of the owners unless other- P.O. BOX 2112 wise indicated. Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 Typography by G & S Typesetting, Inc., Library of Congress Austin, Texas Cataloging-in-Publication Data Printed by Typecraft, Inc., Pasadena, California Walsh, John, 1937- Bound by Roswell Bookbinding, Phoenix, Jan Steen : the Drawing lesson / John Walsh, Arizona p. cm.—(Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographic references. ISBN 0-89326-392-4 1. Steen, Jan, 1626-1679 Drawing lesson. 2. Steen, Jan, 1626-1679—Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series. ND653.S8A64 1996 759.9492—dc20 96-3913 CIP CONTENTS Introduction i A Familiar Face 5 Picturing the Workshop 27 The Training of a Painter 43 Another Look Around 61 Notes on the Literature 78 Acknowledgments 88 Final page folds out, providing a reference color plate of The Drawing Lesson INTRODUCTION In a spacious vaulted room a painter leans over to correct a drawing by one of his two pupils, a young boy and a beautifully dressed girl, who look on [FIGURE i and FOLDOUT].