Rationale, Design and Performance of the Hydra Multiprocessor 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Organization and Architecture Designing for Performance Ninth Edition

COMPUTER ORGANIZATION AND ARCHITECTURE DESIGNING FOR PERFORMANCE NINTH EDITION William Stallings Boston Columbus Indianapolis New York San Francisco Upper Saddle River Amsterdam Cape Town Dubai London Madrid Milan Munich Paris Montréal Toronto Delhi Mexico City São Paulo Sydney Hong Kong Seoul Singapore Taipei Tokyo Editorial Director: Marcia Horton Designer: Bruce Kenselaar Executive Editor: Tracy Dunkelberger Manager, Visual Research: Karen Sanatar Associate Editor: Carole Snyder Manager, Rights and Permissions: Mike Joyce Director of Marketing: Patrice Jones Text Permission Coordinator: Jen Roach Marketing Manager: Yez Alayan Cover Art: Charles Bowman/Robert Harding Marketing Coordinator: Kathryn Ferranti Lead Media Project Manager: Daniel Sandin Marketing Assistant: Emma Snider Full-Service Project Management: Shiny Rajesh/ Director of Production: Vince O’Brien Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Managing Editor: Jeff Holcomb Composition: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Production Project Manager: Kayla Smith-Tarbox Printer/Binder: Edward Brothers Production Editor: Pat Brown Cover Printer: Lehigh-Phoenix Color/Hagerstown Manufacturing Buyer: Pat Brown Text Font: Times Ten-Roman Creative Director: Jayne Conte Credits: Figure 2.14: reprinted with permission from The Computer Language Company, Inc. Figure 17.10: Buyya, Rajkumar, High-Performance Cluster Computing: Architectures and Systems, Vol I, 1st edition, ©1999. Reprinted and Electronically reproduced by permission of Pearson Education, Inc. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Figure 17.11: Reprinted with permission from Ethernet Alliance. Credits and acknowledgments borrowed from other sources and reproduced, with permission, in this textbook appear on the appropriate page within text. Copyright © 2013, 2010, 2006 by Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Prentice Hall. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. -

Trends in Electrical Efficiency in Computer Performance

ASSESSING TRENDS IN THE ELECTRICAL EFFICIENCY OF COMPUTATION OVER TIME Jonathan G. Koomey*, Stephen Berard†, Marla Sanchez††, Henry Wong** * Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Stanford University †Microsoft Corporation ††Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory **Intel Corporation Contact: [email protected], http://www.koomey.com Final report to Microsoft Corporation and Intel Corporation Submitted to IEEE Annals of the History of Computing: August 5, 2009 Released on the web: August 17, 2009 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Information technology (IT) has captured the popular imagination, in part because of the tangible benefits IT brings, but also because the underlying technological trends proceed at easily measurable, remarkably predictable, and unusually rapid rates. The number of transistors on a chip has doubled more or less every two years for decades, a trend that is popularly (but often imprecisely) encapsulated as “Moore’s law”. This article explores the relationship between the performance of computers and the electricity needed to deliver that performance. As shown in Figure ES-1, computations per kWh grew about as fast as performance for desktop computers starting in 1981, doubling every 1.5 years, a pace of change in computational efficiency comparable to that from 1946 to the present. Computations per kWh grew even more rapidly during the vacuum tube computing era and during the transition from tubes to transistors but more slowly during the era of discrete transistors. As expected, the transition from tubes to transistors shows a large jump in computations per kWh. In 1985, the physicist Richard Feynman identified a factor of one hundred billion (1011) possible theoretical improvement in the electricity used per computation. -

Computer Performance Evaluation and Benchmarking

Computer Performance Evaluation and Benchmarking EE 382M Dr. Lizy Kurian John Evolution of Single-Chip Microprocessors 1970’s 1980’s 1990’s 2010s Transistor Count 10K- 100K-1M 1M-100M 100M- 100K 10 B Clock Frequency 0.2- 2-20MHz 20M- 0.1- 2MHz 1GHz 4GHz Instruction/Cycle < 0.1 0.1-0.9 0.9- 2.0 1-100 MIPS/MFLOPS < 0.2 0.2-20 20-2,000 100- 10,000 Hot Chips 2014 (August 2014) AMD KAVERI HOT CHIPS 2014 AMD KAVERI HOTCHIPS 2014 Hotchips 2014 Hotchips 2014 - NVIDIA Power Density in Microprocessors 10000 Sun’s Surface 1000 Rocket Nozzle ) 2 Nuclear Reactor 100 Core 2 8086 10 Hot Plate 8008 Pentium® Power Density (W/cm 8085 4004 386 Processors 286 486 8080 1 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Source: Intel Why Performance Evaluation? • For better Processor Designs • For better Code on Existing Designs • For better Compilers • For better OS and Runtimes Design Analysis Lord Kelvin “To measure is to know.” "If you can not measure it, you can not improve it.“ "I often say that when you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it; but when you cannot measure it, when you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a meagre and unsatisfactory kind; it may be the beginning of knowledge, but you have scarcely in your thoughts advanced to the state of Science, whatever the matter may be." [PLA, vol. 1, "Electrical Units of Measurement", 1883-05-03] Designs evolve based on Analysis • Good designs are impossible without good analysis • Workload Analysis • Processor Analysis Design Analysis Performance Evaluation -

Performance Scalability of N-Tier Application in Virtualized Cloud Environments: Two Case Studies in Vertical and Horizontal Scaling

PERFORMANCE SCALABILITY OF N-TIER APPLICATION IN VIRTUALIZED CLOUD ENVIRONMENTS: TWO CASE STUDIES IN VERTICAL AND HORIZONTAL SCALING A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty by Junhee Park In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Computer Science Georgia Institute of Technology May 2016 Copyright c 2016 by Junhee Park PERFORMANCE SCALABILITY OF N-TIER APPLICATION IN VIRTUALIZED CLOUD ENVIRONMENTS: TWO CASE STUDIES IN VERTICAL AND HORIZONTAL SCALING Approved by: Professor Dr. Calton Pu, Advisor Professor Dr. Shamkant B. Navathe School of Computer Science School of Computer Science Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Professor Dr. Ling Liu Professor Dr. Edward R. Omiecinski School of Computer Science School of Computer Science Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Professor Dr. Qingyang Wang Date Approved: December 11, 2015 School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Louisiana State University To my parents, my wife, and my daughter ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My Ph.D. journey was a precious roller-coaster ride that uniquely accelerated my personal growth. I am extremely grateful to anyone who has supported and walked down this path with me. I want to apologize in advance in case I miss anyone. First and foremost, I am extremely thankful and lucky to work with my advisor, Dr. Calton Pu who guided me throughout my Masters and Ph.D. programs. He first gave me the opportunity to start work in research environment when I was a fresh Master student and gave me an admission to one of the best computer science Ph.D. -

An Algorithmic Theory of Caches by Sridhar Ramachandran

An algorithmic theory of caches by Sridhar Ramachandran Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY. December 1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1999. All rights reserved. Author Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Jan 31, 1999 Certified by / -f Charles E. Leiserson Professor of Computer Science and Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Arthur C. Smith Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students MSSACHUSVTS INSTITUT OF TECHNOLOGY MAR 0 4 2000 LIBRARIES 2 An algorithmic theory of caches by Sridhar Ramachandran Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineeringand Computer Science on Jan 31, 1999 in partialfulfillment of the requirementsfor the degree of Master of Science. Abstract The ideal-cache model, an extension of the RAM model, evaluates the referential locality exhibited by algorithms. The ideal-cache model is characterized by two parameters-the cache size Z, and line length L. As suggested by its name, the ideal-cache model practices automatic, optimal, omniscient replacement algorithm. The performance of an algorithm on the ideal-cache model consists of two measures-the RAM running time, called work complexity, and the number of misses on the ideal cache, called cache complexity. This thesis proposes the ideal-cache model as a "bridging" model for caches in the sense proposed by Valiant [49]. A bridging model for caches serves two purposes. It can be viewed as a hardware "ideal" that influences cache design. On the other hand, it can be used as a powerful tool to design cache-efficient algorithms. -

02 Computer Evolution and Performance

Computer Architecture Faculty Of Computers And Information Technology Second Term 2019- 2020 Dr.Khaled Kh. Sharaf Computer Architecture Chapter 2: Computer Evolution and Performance Computer Architecture LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. A Brief History of Computers. 2. The Evolution of the Intel x86 Architecture 3. Embedded Systems and the ARM 4. Performance Assessment Computer Architecture 1. A BRIEF HISTORY OF COMPUTERS The First Generation: Vacuum Tubes Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer (ENIAC) - Designed and constructed at the University of Pennsylvania, was the world’s first general purpose - Started 1943 and finished 1946 - Decimal (not binary) - 20 accumulators of 10 digits - Programmed manually - 18,000 vacuum tubes by switches - 30 tons -15,000 square feet - 140 kW power consumption - 5,000 additions per second Computer Architecture The First Generation: Vacuum Tubes VON NEUMANN MACHINE • Stored Program concept • Main memory storing programs and data • ALU operating on binary data • Control unit interpreting instructions from memory and executing • Input and output equipment operated by control unit • Princeton Institute for Advanced Studies • IAS • Completed 1952 Computer Architecture Structure of von Neumann machine Structure of the IAS Computer Computer Architecture IAS - details • 1000 x 40 bit words • Binary number • 2 x 20 bit instructions Set of registers (storage in CPU) 1 • Memory buffer register (MBR): Contains a word to be stored in memory or sent to the I/O unit, or is used to receive a word from memory or from the I/O unit. • • Memory address register (MAR): Specifies the address in memory of the word to be written from or read into the MBR. • • Instruction register (IR): Contains the 8-bit opcode instruction being executed. -

Measurement and Rating of Computer Systems Performance

U'Dirlewanger 06.11.2006 14:39 Uhr Seite 1 About this book Werner Dirlewanger ISO has developed a new method to describe and measure performance for a wide range of data processing system types and applications. This solves the pro- blems arising from the great variety of incompatible methods and performance terms which have been proposed and are used. The method is presented in the International Standard ISO/IEC 14756. This textbook is written both for perfor- mance experts and beginners, and academic users. On the one hand it introdu- ces the latest techniques of performance measurement, and on the other hand it Measurement and Rating is a guide on how to apply the standard. The standard also includes additionally two advanced aspects. Firstly, it intro- of duces a rating method to compute those performance values which are actually required by the user entirety (reference values) and a process which compares Computer Systems Performance the reference values with the actual measured ones. This answers the question whether the measured performance satisfies the user entirety requirements. and of Secondly, the standard extends its method to assess the run-time efficiency of software. It introduces a method for quantifying and measuring this property both Software Efficiency for application and system software. Each chapter focuses on a particular aspect of performance measurement which is further illustrated with exercises. Solutions are given for each exercise. An Introduction to the ISO/ IEC 14756 As measurement cannot be performed manually, software tools are needed. All needed software is included on a CD supplied with this book and published by Method and a Guide to its Application the author under GNU license. -

Computer Performance Factors

Advanced Computer Architecture (0630561) Lecture 7 Computer Performance Factors Prof. Kasim M. Al-Aubidy Computer Eng. Dept. ACA-Lecture Objective: ACA-Lecture Performance Metrics: ACA-Lecture Performance Metrics: ACA-Lecture CPU Performance Equation: ACA-Lecture CPU Performance Equation: ACA-Lecture Execution Time (T): T = Ic *CPI *t T: CPU time (seconds/program) needed to execute a program. Ic: Number of Instructions in a given program. CPI: Cycle per Instruction. t: Cycle time. t=1/f, f=clock rate. • The CPI can be divided into TWO component terms; - processor cycles (p) - memory cycles (m) • The instruction cycle may involve (k) memory references, for example; k=4; one for instruction fetch, two for operand fetch, and one for store result. T = Ic *( p + m*k)*t ACA-Lecture System Attributes: T =Ic *(p+m*k)*t The above five performance factors (Ic, p, m, k & t) are influenced by these attributes: FACTORS Ic p m k t Instruction set architecture. X X Compiler technology. X X X CPU implementation & control X X Cache & memory hierarchy X X •The instruction set architecture affects program length and p. •Compiler design affects the values of IC, p & m. •The CPU implementation & control determine the total processor time= p*t •The memory technology & hierarchy design affect the memory access time= k*t 7 ACA-Lecture MIPS Rate: • The processor speed is measured in terms of million instructions per seconds. • MIPS rate varies with respect to: – Clock rate (f). – Instruction count ( Ic ). – CPI of a given machine. I f f * I MIPS = c = = c T *106 CPI *106 N *106 Where N is the total number of clock cycles needed to execute a given program. -

A Review of High Performance Computing

IOSR Journal of Computer Engineering (IOSR-JCE) e-ISSN: 2278-0661, p- ISSN: 2278-8727Volume 16, Issue 1, Ver. VII (Feb. 2014), PP 36-43 www.iosrjournals.org A review of High Performance Computing 1 2 3 G.Sravanthi , B.Grace , V.kamakshamma 1 2 3Department of Computer Science, PBR Visvodaya Institute of Science And Technology, India Abstract: Current high performance computing (HPC) applications are found in many consumers, industrial and research fields. There is a great deal more to remote sensing data than meets the eye, and extracting that information turns out to be a major computational challenges, so the high performance computing (HPC) infrastructure such as MPP (massive parallel processing), clusters, distributed networks or specialized hardware devices are used to provide important architectural developments to accelerate the computations related with information extraction in remote sensing. The focus of HPC has shifted towards enabling the transparent and most efficient utilization of a wide range of capabilities made available over networks. In this paper we review the fundamentals of High Performance Computing (HPC) in a way which is easy to understand and sketch the way to standard computers and supercomputers work, as well as discuss distributed computing and essential aspects to take into account when running scientific calculations in computers. Keywords: High Performance Computing, scientific supercomputing, simulation, computer architecture, MPP, distributed computing, clusters, parallel calculations. I. Introduction High Performance Computing most generally refers to the practice of aggregating computing power in a way that delivers much higher performance than one could get out of a typical desktop computer or workstation in order to solve large problems in science, engineering, or business. -

Performance of a Computer (Chapter 4) Vishwani D

ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Computer Architecture and Design Fall 2013 Performance of a Computer (Chapter 4) Vishwani D. Agrawal & Victor P. Nelson epartment of Electrical and Computer Engineering Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849 ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Performance Fall 2013 . Lecture 1 What is Performance? Response time: the time between the start and completion of a task. Throughput: the total amount of work done in a given time. Some performance measures: MIPS (million instructions per second). MFLOPS (million floating point operations per second), also GFLOPS, TFLOPS (1012), etc. SPEC (System Performance Evaluation Corporation) benchmarks. LINPACK benchmarks, floating point computing, used for supercomputers. Synthetic benchmarks. ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Performance Fall 2013 . Lecture 2 Small and Large Numbers Small Large 10-3 milli m 103 kilo k 10-6 micro μ 106 mega M 10-9 nano n 109 giga G 10-12 pico p 1012 tera T 10-15 femto f 1015 peta P 10-18 atto 1018 exa 10-21 zepto 1021 zetta 10-24 yocto 1024 yotta ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Performance Fall 2013 . Lecture 3 Computer Memory Size Number bits bytes 210 1,024 K Kb KB 220 1,048,576 M Mb MB 230 1,073,741,824 G Gb GB 240 1,099,511,627,776 T Tb TB ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Performance Fall 2013 . Lecture 4 Units for Measuring Performance Time in seconds (s), microseconds (μs), nanoseconds (ns), or picoseconds (ps). Clock cycle Period of the hardware clock Example: one clock cycle means 1 nanosecond for a 1GHz clock frequency (or 1GHz clock rate) CPU time = (CPU clock cycles)/(clock rate) Cycles per instruction (CPI): average number of clock cycles used to execute a computer instruction. -

Central Processing Unit (CPU) the CPU Or Processor Is the "Brain" of the Computer

DAY 13 Processor AKA: central processing unit (CPU) The CPU or processor is the "brain" of the computer. It performs all the operations that the computer does, from simple encoding of text to complex rendering of video. So, the faster the speed of your processor, the faster your computer will run. MEASUREMENTS: • SPEED: GHz example: 3.5GHz • CORES: number of example: quad core BRAND NAMES: • Intel • AMD Objective: • Learn the parts of a computer DAY 18 Memory AKA: Random-access memory (RAM) Usually referred to as "memory", RAM is second to the CPU in determining your computer's performance. It temporarily stores your computer's activities until they are transferred and stored permanently in your hard disk when you shut down or restart MEASUREMENTS: • SIZE: GB (Gigabyte) example: 4GB NOTE: • The more memory your computer has, • the faster it will respond. Objective: • Learn the parts of a computer DAY 18 Hard Drive The hard disk drive, more commonly known as the hard drive or hard disk, is where all data and programs are stored in your computer permanently, unless you delete them. Generally speaking, a hard disk with a higher capacity is always better. MEASUREMENTS: • SIZE: GB or TB (terabyte) example: 500GB or 2TB • TYPES: Disk or Solid State Objective: • Learn the parts of a computer DAY 18 Motherboard The motherboard is where all the other devices in your computer such as the processor, memory, hard disk, and CD/DVD drives are connected. To prevent problems that may lead to loss of data in the future, choose a good quality motherboard. -

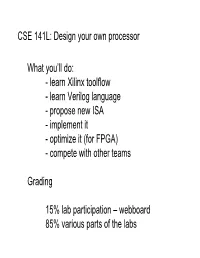

CSE 141L: Design Your Own Processor What You'll

CSE 141L: Design your own processor What you’ll do: - learn Xilinx toolflow - learn Verilog language - propose new ISA - implement it - optimize it (for FPGA) - compete with other teams Grading 15% lab participation – webboard 85% various parts of the labs CSE 141L: Design your own processor Teams - two people - pick someone with similar goals - you keep them to the end of the class - more on the class website: http://www.cse.ucsd.edu/classes/sp08/cse141L/ Course Staff: 141L Instructor: Michael Taylor Email: [email protected] Office Hours: EBU 3b 4110 Tuesday 11:30-12:20 TA: Saturnino Email: [email protected] ebu 3b b260 Lab Hours: TBA (141 TA: Kwangyoon) Æ occasional cameos in 141L http://www-cse.ucsd.edu/classes/sp08/cse141L/ Class Introductions Stand up & tell us: -Name - How long until graduation - What you want to do when you “hit the big time” - What kind of thing you find intellectually interesting What is an FPGA? Next time: (Tuesday) Start working on Xilinx assignment (due next Tuesday) - should be posted Sat will give a tutorial on Verilog today Check the website regularly for updates: http://www.cse.ucsd.edu/classes/sp08/cse141L/ CSE 141: 0 Computer Architecture Professor: Michael Taylor UCSD Department of Computer Science & Engineering RF http://www.cse.ucsd.edu/classes/sp08/cse141/ Computer Architecture from 10,000 feet foo(int x) Class of { .. } application Physics Computer Architecture from 10,000 feet foo(int x) Class of { .. } application An impossibly large gap! In the olden days: “In 1942, just after the United States entered World War II, hundreds of women were employed around the country as Physics computers...” (source: IEEE) The Great Battles in Computer Architecture Are About How to Refine the Abstraction Layers foo(int x) { .