Te Wai Pounamu, New Zealand Circa 1769-1840

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Look Inside 10 Days in the Life of Auckland War Memorial Museum CONTENTS

Look inside 10 days in the life of Auckland War Memorial Museum CONTENTS Ka puāwai ngā mahi o tau kē, Year in Review Ka tōia mai ā tātou kaimātaki i ēnei rā, Ka whakatō hoki i te kākano mō āpōpō. Sharing our Highlights 2014/2015 6 Board Chairman, Taumata-ā-Iwi Chairman and Director’s Report 8 Building on our past, 10 Days in the Life of Auckland War Memorial Museum 10 Engaging with our audiences today, Investing for tomorrow. Governance Trust Board 14 We are pleased to present our Taumata-ā-Iwi 16 Annual Report 2014/2015. Executive Team 18 Pacific Advisory Group 20 Youth Advisory Group 21 Governance Statement 22 Board Committees and Terms of Reference 24 Partnerships Auckland Museum Institute 26 Auckland Museum Circle Foundation 28 Funders, Partners and Supporters 30 BioBlitz 2014 Tungaru: The Kiribati project Research Update 32 Performance Te Pahi Medal Statement of Service Performance 38 Auditor’s Report: Statement of Service Performance 49 Entangled Islands Contact Information 51 exhibition Illuminate projections onto the Museum Financial Performance Financial Statements 54 Dissection of Auditor’s Report: Financial Statements 88 Great White Shark Financial Commentary 90 Flying over the Antarctic This page and throughout: Nautilus Shell SECTION SECTION Year in Review 4 5 YEAR IN REVIEW YEAR IN REVIEW Sharing our Highlights 2014/2015 A strong, A compelling Accessible Active sustainable destination ‘beyond participant foundation the walls’ in Auckland 19% 854,177 1 million 8 scholars supported by the Museum to reduction in overall emissions -

Te Runanga 0 Ngai Tahu Traditional Role of the Rona!Sa

:I: Mouru Pasco Maaka, who told him he was the last Maaka. In reply ::I: William told Aritaku that he had an unmerried sister Ani, m (nee Haberfield, also Metzger) in Murihiku. Ani and Aritaku met and went on to marry. m They established themselves in the area of Waimarama -0 and went on to have many children. -a o Mouru attended Greenhills Primary School and o ::D then moved on to Southland Girls' High School. She ::D showed academic ability and wanted to be a journalist, o but eventually ended up developing photographs. The o -a advantage of that was that today we have heaps of -a beautiful photos of our tlpuna which we regard as o priceless taolsa. o ::D Mouru went on to marry Nicholas James Metzger ::D in 1932. Nick's grandfather was German but was o educated in England before coming to New Zealand. o » Their first son, Nicholas Graham "Tiny" was born the year » they were married. Another child did not follow until 1943. -I , around home and relished the responsibility. She Mouru had had her hopes pinned on a dainty little girl 2S attended Raetihi School and later was a boarder at but instead she gave birth to a 13lb 40z boy called Gary " James. Turakina Maori Girls' College in Marton. She learnt the teachings of both the Ratana and Methodist churches. Mouru went to her family's tlU island Pikomamaku In 1944 Ruruhira took up a position at Te Rahui nui almost every season of her life. She excelled at Wahine Methodist Hostel for Maori girls in Hamilton cooking - the priest at her funeral remarked that "she founded by Princess Te Puea Herangi. -

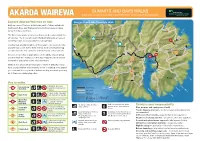

Summits and Bays Walks

DOC Information Centre Sumner Taylors Mistake Godley Head Halswell Akaroa Lyttelton Harbour 75km SUMMITSFerry AND BAYS WALKS AKAROA WAIREWA Explore the country around Akaroa and Little RiverPort Levy on these family friendly walks Explore Akaroa/Wairewa on foot Choose Your Banks Peninsula Walk Explore some of the less well-known parts of Akaroa Harbour,Tai Tapu Pigeon Bay the Eastern Bays and Wairewa (the Little River area) on these Little Akaloa family friendly adventures. Chorlton Road Okains Bay The three easy walks are accessed on sealed roads suitable for Te Ara P¯ataka Track Western Valley Road all vehicles. The more remote and harder tramps are accessed Te Ara P¯ataka Track Packhorse Hut Big Hill Road 3 Okains Bay via steep roads, most unsuitable for campervans. Road Use the map and information on this page to choose your route Summit Road Museum Rod Donald Hut and see how to get there. Then refer to the more detailed map 75 Le Bons Okains Bay Camerons Track Bay and directions to find out more and follow your selected route. Road Lavericks Ridge Road Hilltop Tavern 75 7 Duvauchelle Panama Road Choose a route that is appropriate for the ability of your group 1 4WD only Christchurch Barrys and the weather conditions on the day. Prepare using the track Bay 2 Little River Robinsons 6 Bay information and safety notes in this brochure. Reserve Road French O¯ nawe Kinloch Road Farm Lake Ellesmere / Okuti Valley Summit Road Walks in this brochure are arranged in order of difficulty. If you Te Waihora Road Reynolds Valley have young children or your family is new to walking, we suggest Little River Rail Trail Road Saddle Hill you start with the easy walk in Robinsons Bay and work your way Lake Forsyth / Akaroa Te Roto o Wairewa 4 Jubilee Road 4WD only up to the more challenging hikes. -

Management Guidelines for Surfing Resources

Management Guidelines for Surfing Resources Version History Version Date Comment Approved for release by Beta version release of Beta 1st October 2018 first edition for initial feedback period Ed Atkin Version 1 following V1 31st August 2019 feedback period Ed Atkin Please consider the environment before printing this document Management Guidelines for Surfing Resources This document was developed as part of the Ministry for Businesses, Innovation and Employment funded research project: Remote Sensing, Classification and Management Guidelines for Surf Breaks of National and Regional Significance. Disclaimer These guidelines have been prepared by researchers from University of Waikato, eCoast Marine Consulting and Research, and Hume Consulting Ltd, under the guidance of a steering committee comprising representation from: Auckland Council; Department of Conservation; Landcare Research; Lincoln University; Waikato Regional Council; Surfbreak Protection Society; and, Surf Life Saving New Zealand. This document has been peer reviewed by leading surf break management and preservation practitioners, and experts in coastal processes, planning and policy. Many thanks to Professor Andrew Short, Graeme Silver, Dr Greg Borne, Associate Professor Hamish Rennie, James Carley, Matt McNeil, Michael Gunson, Rick Liefting, Dr Shaun Awatere, Shane Orchard and Dr Tony Butt. The authors have used the best available information in preparing this document. Nevertheless, none of the organisations involved in its preparation accept any liability, whether direct, indirect or consequential, arising out of the provision of information in this report. While every effort has been made to ensure that these guidelines are clear and accurate, none of the aforementioned contributors and involved parties will be held responsible for any action arising out of its use. -

Autahi Istory

autahi a moko ises the art form ce of istory "re Tau case. gUlng I ityof apapa Sarah Sylvia lorraine Koher 1917-May 19, 2001 Earlier this year while i ton I visited a remarkable son of Ngai Tahu - Mi aSM. Papaki mai nga hau ate ao ki rungaAoraki, ka rewa nga Mick- from the Picton ~y family - did not have huka hei roimata, ka tere at wa Ki ta Moana- a high profile yet his is a story of extraordinary talent, of nui-a-Kiwa. Tahuri ornata t tf fa bravery, adve uer~d and a life of service to THE NGAI TAHU MAGAZINE 6u Kawai kei te Waipounamu Ngal TOahurf MakaririlWinter 2001 others. Ngati Huirapa, ki a Kati Waewae, Ngai Tahu, If Mickhad aI', he would have EDITOR Gabrielle Huria Mamoe, Waitaha nui tonu. Te hunaonga 0 Rewati Been one of the s Zealand sporting Tuhorouta Kohere raua ko Keita Kaikiri Paratene. Haruru scene. ASSISTANT Adrienne Anderson ana hoki te hinganga 0 te kaitiaki a Rangiatea. Haehae EDITOR At the onset ana te ngakau. Aue taukuri e. editorial playing first-class r CONTRIBUTORS Emalene Belczacki many to be one of Helen Brown GABRIELLE HURIA Black Douglas Waipapa (Flutey) Ross Caiman And so he war, Where in both Egypt and Cook Donald Couch Italy ha Wills resent the New Zealand Army Suzanne Ellison Jane Huria Tana koutou katoa. Ka nui taku mihi ki a koutou i tanei wa a te makariri. team In no He panui tenei ki a koutou. I hinga Blade Jones Wr Ta moko has experienced a renaissance in recent times. -

2013–2014 Annual Report

OTAGO MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2013–2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Chairperson’s Foreword 4 Director’s Review of the Year 5 Otago Museum Trust Board 6 Māori Advisory Committee 7 Honorary Curators 7 Association of Friends of the Otago Museum 7 Acknowledgements 8 Otago Museum Staff 9 Goal One – A World-class Collection 12 Goal Two – Engaging Our Community 17 Goal Three – Business Sustainability 21 Goal Four – An Outward-looking and Inclusive Culture 24 Visitor Comments 27 Looking Forward 28 Statement of Service Performance 29 Financial Statements 53 2 INTRODUCTION Leadership at the Otago Museum Each new director builds on the wider community, taking into account is generational, with each Museum legacy of those that have come the many varied functions of the director’s tenure being an average of before. Dr Ian Griffin, trained as a Museum and its obligations to service 18 years. This length of service scientist and physicist, has a passion its stakeholders and communities. invariably defines the culture and for science communication and organisational structure of the informal learning engagement. A strategy planning workshop held institution. Previous directors have He brings a new approach to, and in November 2013 was attended by placed emphasis on building and awareness of, the potential and many sectors of the Museum’s wider inspiring research into the collection, importance of the Museum, not only community, from Museum staff and communicating our region’s history as a visitor attraction but as a centre the Otago Museum Trust Board, to and inspiring our community. for learning. educators and academics, to City, District and Regional Councillors, For the past 20 years, the focus has Our aim is to develop a fit for purpose Kāi Tahu representatives, business been on building the Museum into a repository for the Museum’s collection, operators and community workers major visitor attraction and a strategy address the need to research history in the Otago region. -

H.D. Skinner's Use of Associates Within the Colonial

Tuhinga 26: 20–30 Copyright © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2015) H.D.Skinner’s use of associates within the colonial administrative structure of the Cook Islands in the development of Otago Museum’s Cook Islands collections Ian Wards National Military Heritage Charitable Trust, PO Box 6512, Marion Square, Wellington, New Zealand ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: During his tenure at Otago Museum (1919–57), H.D.Skinner assembled the largest Cook Islands collection of any museum in New Zealand. This paper shows that New Zealand’s colonial administrative structure was pivotal in the development of these collections, but that they were also the result of complex human interactions, motivations and emotions. Through an analysis of Skinner’s written correspondence, examples are discussed that show his ability to establish relationships where objects were donated as expressions of personal friendship to Otago Museum. The structure of the resulting collection is also examined. This draws out Skinner’s personal interest in typological study of adzes and objects made of stone and bone, but also highlights the increasing scarcity of traditional material culture in the Cook Islands by the mid-twentieth century, due in part to the activities of other collectors and museums. KEYWORDS: H.D.Skinner, Otago Museum, Cook Islands, colonialism, material culture. Introduction individuals, exchanges with museums, private donations and, significantly, the purchase by the New Zealand government During his tenure as ethnologist (1919–57) and, later, of the Oldman collection in 1948, Otago Museum’s Cook director of Otago Museum, Henry Devenish Skinner Islands collection grew to be the largest in New Zealand. -

Rod Donald Banks Peninsula Trust 2020–2030

Rod Donald Banks Peninsula Trust 2020–2030 Striding Forward | Hikoi Whakamua . STRATEGIC PLAN March 2020 TŌ TĀTOU TIROHANGA OUR VISION Ko te whakawhanake kaitiaki taiao nā te whakahōu ara hīkoi, ara paihikara, te whakaniko rerenga rauropi, te whakamana mātauranga me te mahi tahi ki ngā tāngata e kaingākau kaha ana ki Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū hoki. Developing environmental guardians of the future through improved public walking and biking access, enhancing biodiversity, promoting knowledge and working in partnership with others who share our commitment to Banks Peninsula. 2 Success Story 3 Reasons for our Success Christchurch City Council founded Rod Donald Banks Independence and We are highly cost The Trust has Peninsula Trust in 2010, as a our capital base are effective. maximised the charitable entity to support our core strengths Council investment. sustainable management, 1 enabling us to: 2 3 conservation and recreation on the peninsula. Capital from the sale of farms endowed • Attract highly skilled • Projects to date have • We estimate a five to earlier peninsula councils voluntary Trustees used only 35% of the fold gain on initial was transferred to the Trust to • Seize opportunities as original capital investment through facilitate this. they present • Staff work on partnerships The first step taken by the Trust was a • Form project projects, not funding • Our projects mean stocktake of other agencies and groups with partnerships applications the Council’s Public overlapping mandates working on Banks • Contractor based Open Space Strategy Peninsula. The objective was to identify gaps model keeps overheads is on track despite the in the work in progress and how, as a new low earthquakes entity, the Trust could best add value. -

Peter Entwisle, Behold the Moon: the European Occupation of the Dunedin District 1770-1848, Reviewed

B B REVIEWS (BOOKS) 103 B B Perhaps anxious to avoid concluding on such a grim and depressing note, Puckey instead ends by discussing the modern-day settlement of the Muriwhenua Treaty claims, B a process that has dragged out over more than two decades. The modest re-capitalisation B of far northern iwi is unlikely on its own to prove sufficient to reverse the socio-economic fortunes of Māori in the area. But understanding the origins of a problem can often prove crucial in overcoming it, and in this respect Puckey’s book should be required reading B for all those interested in the future fate of the Far North. B VINCENT O’MALLEY HistoryWorks B B Behold the Moon: The European Occupation of the Dunedin District 1770–1848 (revised edition). By Peter Entwisle. Port Daniel Press with the assistance of the Alfred and Isabel Reed Trust administered by the Otago Settlers’ Association, Dunedin, 2010. 300pp. B B Paperback: NZ price $49. ISBN: 978-0-473-17534-4. DERIVING ITS IMAGINATIVE NAME from a Māori chant transcribed by David Samwell at Queen Charlotte Sound during Cook’s third voyage there in 1777, this book is the B revised version of Peter Entwisle’s 1998 one of the same name. Both books have as their B initial frame of reference a brief contextual description of the wider socio-political and B cultural worlds of Europeans in the time leading up to the arrival of sealers, whalers, B traders and eventually missionaries in the South Island of New Zealand. Supporting B his thesis that the beginnings of the European occupation of the Dunedin district were B inextricably linked with the early arrival of small parties of such people in coastal Otago B and Southland, Entwisle describes their interaction and assimilation into small, dispersed B Māori communities that became nuclei for exchange. -

Review of the Archaeology of Foveaux Strait, New Zealand, by Chris Jacomb, Richard Walter and Chris

REVIEW OF THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF FOVEAUX STRAIT, NEW ZEALAND CHRIS JACOMB, RICHARD WALTER and CHRIS JENNINGS University of Otago The waters and shores of Foveaux Strait make up one of the coldest, windiest environments in New Zealand and, lying well outside the tropical horticulture zone, could not have been less like the environment of the Polynesian homelands. Yet they contain an extensive archaeological record which includes a low density but wide distribution of sites, as well as some rich artefact assemblages held in private and public collections. The record is not well dated but the few radiocarbon dates and the material culture and economy suggest that occupation commenced as early there as in any other part of the country. In considering why people moved so far south so early, Lockerbie (1959) rejected push factors such as demographic or resource pressures and argued that there must have been some serious attractors (pull factors) in play. Working today with a much shorter chronology, push motives seem even less likely but it is difficult to imagine what the pull factors might have been. Foveaux Strait settlement coincides with the expansion of moa hunting in southern New Zealand but there were never many moa (Dinornithiformes) along the south coast and moa bone is rare in south coast middens. There are resident populations of sea mammals including New Zealand fur seal (Arctocephalus forsterii) and sea lion (Phocarctos hookeri) but these were not restricted to Foveaux Strait (Smith 1989: 208), nor do the sites show high levels of sea mammal predation. Today, one of the most important seasonal resources is the sooty shearwater (mutton bird or titi(Puffinus) griseus) but again, there are no strong archaeological indicators of an early emphasis on mutton birding (Anderson 1995, 2001; Sutton and Marshall 1980). -

Harbour Northern Bays Eastern Bays Southern Bays Kaitorete Spit Akaroa Harbour

File Ref: C14043_007a_A3L_CE_NC_BanksP_20151201.mxd d n ge e L 1 2 Landscape Character Areas (2007) 1 District Plan Coastal Environment Northern Coastal Natural Character (NC) Port Outstanding NC Levy 2 Diamond Pigeon Bays Very High NC Harbour Bay 5 7 High NC 3 Harbour NC in Coastal Environment Charteris Bay Akaloa 4 9 3 6 ° 11 Okains 1 0 Bay 0 6 km 8 1:150,000 @ A3 Sources: Sourced from Topo50 Map Series. Crown Copyright Reserved 1 3 2 9 2 8 Projection: 1 2 NZGD 2000 New Zealand Transverse Mercator Hill 2 0 Le Bons Top Bay 2 6 1 4 River 3 0 Barrys PRE HEARING AMENDMENTS 2 7 Bay 1 9 MAP 2 Lake Takamatua 2 1 Hickory BANKS PENINSULA 1 5 LANDSCAPE STUDY REVIEW Ellesmere Bay Bay 2 5 Akaroa Coastal Natural Character - Evaluation of CNCL areas 2 2 Harbour Goughs 3 1 1 8 Bay Wainui Date: 01 December 2015 Fishermans Revision: 5 Kaitorete 1 6 Plan Prepared for CCC 2 4 Bay by Boffa Miskell Limited Project Manager: Yvonne Pfluger Spit 2 3 1 7 Stony Drawn: BMc | Checked: YP Te Oka Bay This graphic has been prepared by Boffa Miskell Limited on the specific instructions of our Client. It is solely for our Bay Clients use in accordance with the agreed scope of work. Any use or reliance by a third party is at that partys own risk. Peraki Where information has been supplied by the Client or Flea obtained from other external sources, it has been assumed Bay Eastern that it is accurate. -

TE-KARAKA-73.Pdf

ABOUT NGĀI TAHU–ABOUT NEW ZEALAND–ABOUT YOU KAHURU/AUTUMN 2017 $7.95 73 NOW AVAILABLE TO DOWNLOAD ON APPLE AND ANDROID DEVICES It will tell you the name of the artist and song title as it’s playing LIVE - you can even change the language to te reo Maori DOWNLOAD IT NOW ii TE KARAKA KAHURU 2017 KAHURU/AUTUMN 2017 73 10 WALKING THE TALK At the end of 2016, Tā Mark Solomon stepped down as Kaiwhakahaere NGĀ HAU of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. Kaituhi Adrienne Rewi, Mark Revington and E WHĀ David Slack reflect upon his 18 years of service. FROM THE EDITOR 10 In this issue we take the opportunity to acknowledge Tā Mark Solomon on his 18 years as Kaiwhakahaere o Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu (pages 10 - 15). We reflect upon his contribution to Ngāi Tahu, to Māoridom, and in fact to the whole of Aotearoa. Over the last 18 years he has been a constant presence, playing an instrumental role as Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu found its feet post- Settlement, forming strategic relationships with the Crown and other iwi, and guiding Ngāi Tahu through difficult times, such as the Christchurch earthquakes. The years he has dedicated to the iwi, and the affably humble way he has always carried himself, mean he will be missed by many. 16 TE WHAKA A TE WERA On pages 30 - 33 we discuss the issue Paterson Inlet off the coast of Rakiura is the largest mātaitai in the country, of whenua in Tūrangawaewae – Where using customary knowledge of mahinga kai to preserve the fisheries for future Do We Stand? Tūrangawaewae means “a generations.