The Game of Go: Speculations on Its Origins and Symbolism in Ancient China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laozi Zhongjing)

A Study of the Central Scripture of Laozi (Laozi zhongjing) Alexandre Iliouchine A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts, Department of East Asian Studies McGill University January 2011 Copyright Alexandre Iliouchine © 2011 ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements......................................................................................... v Abstract/Résumé............................................................................................. vii Conventions and Abbreviations.................................................................... viii Introduction..................................................................................................... 1 On the Word ―Daoist‖............................................................................. 1 A Brief Introduction to the Central Scripture of Laozi........................... 3 Key Terms and Concepts: Jing, Qi, Shen and Xian................................ 5 The State of the Field.............................................................................. 9 The Aim of This Study............................................................................ 13 Chapter 1: Versions, Layers, Dates............................................................... 14 1.1 Versions............................................................................................. 15 1.1.1 The Transmitted Versions..................................................... 16 1.1.2 The Dunhuang Version........................................................ -

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 3 • Issue 1 January/February 2012 Chess Gambits Chess Gambits The Immortal Game Canada and Chess Anderssen- Vs. -Kieseritzky Bill Wall’s Top 10 Chess software programs C Seraphim Press White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents Editorial~ “My Move” 4 contents Feature~ Chess and Canada 5 Article~ Bill Wall’s Top 10 Software Programs 9 INTERACTIVE CONTENT ________________ Feature~ The Incomparable Kasparov 10 • Click on title in Table of Contents Article~ Chess Variants 17 to move directly to Unorthodox Chess Variations page. • Click on “White Feature~ Proof Games 21 Knight Review” on the top of each page to return to ARTICLE~ The Immortal Game 22 Table of Contents. Anderssen Vrs. Kieseritzky • Click on red type to continue to next page ARTICLE~ News Around the World 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW~ Kasparov on Kasparov Pt. 1 25 • Click on email to Pt.One, 1973-1985 open up email program Feature~ Chess Gambits 26 • Click up URLs to go to websites. ANNOTATED GAME~ Bareev Vs. Kasparov 30 COMMENTARY~ “Ask Bill” 31 White Knight Review January/February 2012 White Knight Review January/February 2012 Feature My Move Editorial - Jerry Wall [email protected] Well it has been over a year now since we started this publication. It is not easy putting together a 32 page magazine on chess White Knight every couple of months but it certainly has been rewarding (maybe not so Review much financially but then that really never was Chess E-Magazine the goal). -

2.) COMMUNITY COLLEGE: Maricopa Co

GENERAL STUDIES COURSE PROPOSAL COVER FORM (ONE COURSE PER FORM) 1.) DATE: 3/26/19 2.) COMMUNITY COLLEGE: Maricopa Co. Comm. College District 3.) PROPOSED COURSE: Prefix: GST Number: 202 Title: Games, Culture, and Aesthetics Credits: 3 CROSS LISTED WITH: Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: ; Prefix: Number: . 4.) COMMUNITY COLLEGE INITIATOR: KEITH ANDERSON PHONE: 480-654-7300 EMAIL: [email protected] ELIGIBILITY: Courses must have a current Course Equivalency Guide (CEG) evaluation. Courses evaluated as NT (non- transferable are not eligible for the General Studies Program. MANDATORY REVIEW: The above specified course is undergoing Mandatory Review for the following Core or Awareness Area (only one area is permitted; if a course meets more than one Core or Awareness Area, please submit a separate Mandatory Review Cover Form for each Area). POLICY: The General Studies Council (GSC) Policies and Procedures requires the review of previously approved community college courses every five years, to verify that they continue to meet the requirements of Core or Awareness Areas already assigned to these courses. This review is also necessary as the General Studies program evolves. AREA(S) PROPOSED COURSE WILL SERVE: A course may be proposed for more than one core or awareness area. Although a course may satisfy a core area requirement and an awareness area requirement concurrently, a course may not be used to satisfy requirements in two core or awareness areas simultaneously, even if approved for those areas. With departmental consent, an approved General Studies course may be counted toward both the General Studies requirements and the major program of study. -

1999/1 Layout

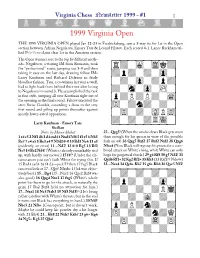

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #1 1 1999 Virginia Open THE 1999 VIRGINIA OPEN played Jan 22-24 in Fredricksburg, saw a 3-way tie for 1st in the Open section between Adrian Negulescu, Emory Tate & Leonid Filatov. Each scored 4-1. Lance Rackham tal- 1 1 lied 5 ⁄2- ⁄2 to claim clear 1st in the Amateur section. The Open winners rose to the top by different meth- ‹óóóóóóóó‹ ods. Negulescu, a visiting IM from Rumania, took õÏ›‹Ò‹ÌÙ›ú the “professional” route, jumping out 3-0 and then taking it easy on the last day, drawing fellow IMs õ›‡›‹›‹·‹ú Larry Kaufman and Richard Delaune in fairly bloodless fashion. Tate, a co-winner last year as well, õ‹›‹·‹›‡›ú had to fight back from behind this time after losing to Negulescu in round 3. He accomplished the task õ›‹Â‹·‹„‹ú in fine style, jumping all over Kaufman right out of õ‡›fi›fi›‹Ôú the opening in the final round. Filatov executed the semi Swiss Gambit, conceding a draw in the very õfl‹›‰›‹›‹ú first round and piling up points thereafter against mostly lower-rated opposition. õ‹fl‹›‹Áfiflú õ›‹›‹›ÍÛ‹ú Larry Kaufman - Emory Tate Sicilian ‹ìììììììì‹ Notes by Macon Shibut 25...Qxg5! (When the smoke clears Black gets more 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 f3 e5 6 Nb3 than enough for his queen in view of the possible Be7 7 c4 a5 8 Be3 a4 9 N3d2 0-0 10 Bd3 Nc6 11 a3 fork on e4) 26 Qxg5 Rxf2 27 Rxf2 Nxf2 28 Qxg6 (evidently an error) 11...Nd7! 12 0-0 Bg5 13 Bf2 Nfxe4 (Now Black will regroup his pieces for a com- Nc5 14 Bc2 Nd4! (White is already remarkably tied bined attack on White’s king, while White can only up, with hardly any moves.) 15 f4!? (Under the cir- hope for perpetual check.) 29 g4 Rf8 30 g5 Nd2! 31 cumstances you can’t fault White for trying this. -

Religion in China BKGA 85 Religion Inchina and Bernhard Scheid Edited by Max Deeg Major Concepts and Minority Positions MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.)

Religions of foreign origin have shaped Chinese cultural history much stronger than generally assumed and continue to have impact on Chinese society in varying regional degrees. The essays collected in the present volume put a special emphasis on these “foreign” and less familiar aspects of Chinese religion. Apart from an introductory article on Daoism (the BKGA 85 BKGA Religion in China prototypical autochthonous religion of China), the volume reflects China’s encounter with religions of the so-called Western Regions, starting from the adoption of Indian Buddhism to early settlements of religious minorities from the Near East (Islam, Christianity, and Judaism) and the early modern debates between Confucians and Christian missionaries. Contemporary Major Concepts and religious minorities, their specific social problems, and their regional diversities are discussed in the cases of Abrahamitic traditions in China. The volume therefore contributes to our understanding of most recent and Minority Positions potentially violent religio-political phenomena such as, for instance, Islamist movements in the People’s Republic of China. Religion in China Religion ∙ Max DEEG is Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Cardiff. His research interests include in particular Buddhist narratives and their roles for the construction of identity in premodern Buddhist communities. Bernhard SCHEID is a senior research fellow at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. His research focuses on the history of Japanese religions and the interaction of Buddhism with local religions, in particular with Japanese Shintō. Max Deeg, Bernhard Scheid (eds.) Deeg, Max Bernhard ISBN 978-3-7001-7759-3 Edited by Max Deeg and Bernhard Scheid Printed and bound in the EU SBph 862 MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.) RELIGION IN CHINA: MAJOR CONCEPTS AND MINORITY POSITIONS ÖSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE SITZUNGSBERICHTE, 862. -

Handling of Out-Of-Vocabulary Words in Japanese-English

International Journal of Asian Language Processing 29(2):61-86 61 The Syntactic Evolvement of the Chinese Word “Wei” Yan Li School of Foreign Languages, Shaanxi Normal University Xi’an, China, 710062 [email protected] Abstract Based on Beijing University CCL corpus, this article investigated the functions and meanings of the word “Wei”(维) in different dynasties. “维” could be a word in ancient times while it functions as verb, noun, pronoun, preposition, auxiliary word, etc.. But from West Jin Dynasty there appeared disyllabic words including “维” and the situation of co-existing of monosyllabic words and disyllabic words lasted till the Republic of China. Now “维” as a word disappeared and only as a morpheme in disyllabic or multisyllabic words. The transformation from a monosyllabic word to a monosyllabic morpheme is a very common phenomenon in Chinese. Keywords “Wei”(维), syntactic evolvement, morphemization 1. Introduction The word “Wei”(维) is a very common morpheme in modern Chinese, but its evolution is of specialty which is worth exploring. In Chinese history, a morpheme has ever been a word which could be used independently, but in modern Chinese, many monosyllabic words lower their status to monosyllabic morphemes (Dong Xiufang, 2004). “维”was a word in ancient times, which is pictophonetic while its character from 糸(mì)and 隹(zhuī). “糸” means “rope, string”. The combination of “糸”and “隹” means ‘to draw forth more than three ropes from a higher place to the ground and enclose a hollow cone’. The original meaning is “rope” which is used to form a cone. -

Life Cycle Patterns of Cognitive Performance Over the Long

Life cycle patterns of cognitive performance over the long run Anthony Strittmattera,1 , Uwe Sundeb,1,2, and Dainis Zegnersc,1 aCenter for Research in Economics and Statistics (CREST)/Ecole´ nationale de la statistique et de l’administration economique´ Paris (ENSAE), Institut Polytechnique Paris, 91764 Palaiseau Cedex, France; bEconomics Department, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat¨ Munchen,¨ 80539 Munchen,¨ Germany; and cRotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University, 3062 PA Rotterdam, The Netherlands Edited by Robert Moffit, John Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Jose A. Scheinkman September 21, 2020 (received for review April 8, 2020) Little is known about how the age pattern in individual perfor- demanding tasks, however, and are limited in terms of compara- mance in cognitively demanding tasks changed over the past bility, technological work environment, labor market institutions, century. The main difficulty for measuring such life cycle per- and demand factors, which all exhibit variation over time and formance patterns and their dynamics over time is related to across skill groups (1, 19). Investigations that account for changes the construction of a reliable measure that is comparable across in skill demand have found evidence for a peak in performance individuals and over time and not affected by changes in technol- potential around ages of 35 to 44 y (20) but are limited to short ogy or other environmental factors. This study presents evidence observation periods that prevent an analysis of the dynamics for the dynamics of life cycle patterns of cognitive performance of the age–performance profile over time and across cohorts. over the past 125 y based on an analysis of data from profes- An additional problem is related to measuring productivity or sional chess tournaments. -

The AGA Song Book up to Date

3rd Edition Songs, Poems, Stories and More! Edited by Bob Felice Published by The American Go Association P.O. Box 397, Old Chelsea Station New York, N.Y., 10113-0397 Copyright 1998, 2002, 2006 in the U.S.A. by the American Go Association, except where noted. Cover illustration by Jim Rodgers. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without prior written permission of the copyright holder, except for brief quotations used as part of a critical review. Introductions Introduction to the 1st Edition When I attended my first Go Congress three years ago I was astounded by the sheer number of silly Go songs everyone knew. At the next Congress, I wondered if all these musical treasures had ever been printed. Some research revealed that the late Bob High had put together three collections of Go songs, but the last of these appeared in 1990. Very few people had these song books, and some, like me, weren’t even aware that they existed. While new songs had been printed in the American Go Journal, there was clearly a need for a new collection of Go songs. Last year I decided to do whatever I could to bring the AGA Song Book up to date. I wanted to collect as many of the old songs as I could find, as well as the new songs that had been written since Bob High’s last song book. You are holding in your hands the book I was looking for two years ago. -

Mythical Image of “Queen Mother of the West” and Metaphysical Concept of Chinese Jade Worship in Classic of Mountains and Seas

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 21, Issue11, Ver. 6 (Nov. 2016) PP 39-46 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Mythical Image of “Queen Mother of the West” and Metaphysical Concept of Chinese Jade Worship in Classic of Mountains and Seas Juan Wu1 (School of Foreign Language,Beijing Institute of Technology, China) Abstract: This paper focuses on the mythological image, the Queen Mother of the West in Classic of Mountains and Seas, to explore the hiding history and mental reality behind the fantastic literary images, to unveil the origin of jade worship, which plays an significant role in the 8000-year-old history of Eastern Asian jade culture, to elucidate the genetic mechanism of the jade worship budded in the Shang and Zhou dynasties, so that we can have an overview of the tremendous influence it has on Chinese civilization, and illustrate its psychological role in molding the national jade worship and promoting the economic value of jade business. Key words: Mythical Image, Mythological Concept, Jade Worship, Classic of Mountains and Seas I. WHITE JADE RING AND QUEEN MOTHER OF THE WEST As for the foundation and succession myths of early Chinese dynasties, Allan holds that “Ancient Chinese literature contains few myths in the traditional sense of stories of the supernatural but much history” (Allan, 1981: ix) and “history, as it appears in the major texts from the classical period of early China (fifth-first centuries B.C.),has come to function like myth” (Allan, 1981: 10). While “the problem of myth for Western philosophers is a problem of interpreting the meaning of myths and the phenomenon of myth-making” as Allan remarks, “the problem of myth for the sinologist is one of finding any myths to interpret and of explaining why there are so few.” (Allen, 1991: 19) To decode why white jade enjoys a prominent position in the Chinese culture, the underlying conceptual structure and unique culture genes should be investigated. -

Lesson Plans for Go in Schools

Go Lesson Plans 1 Lesson Plans for Go in Schools By Gordon E. Castanza, Ed. D. October 19, 2011 Published By Rittenberg Consulting Group 7806 108th St. NW Gig Harbor, WA 98332 253-853-4831 ©Gordon E. Castanza, Ed. D. 10/19/11 DRAFT Go Lesson Plans 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 4 Purpose/Rationale ........................................................................................................................... 5 Lesson Plan One ............................................................................................................................. 7 Basic Ideas .................................................................................................................................. 7 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 11 The Puzzle ................................................................................................................................. 13 Surround to Capture .................................................................................................................. 14 First Capture Go ........................................................................................................................ 16 Lesson Plan Two ........................................................................................................................... 19 Units & -

The Burden of Choice, the Complexity of the World and Its Reduction: the Game of Go/Weiqi As a Practice of "Empirical Metaphysics"

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330509941 The Burden of Choice, the Complexity of the World and Its Reduction: The Game of Go/Weiqi as a Practice of "Empirical Metaphysics" Article in Avant · January 2019 DOI: 10.26913/avant.2018.03.05 CITATIONS READS 0 76 1 author: Andrzej Wojciech Nowak Adam Mickiewicz University 27 PUBLICATIONS 18 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Metrological Sovereignity, Suwerenność metrologiczna View project Ontological Politics View project All content following this page was uploaded by Andrzej Wojciech Nowak on 20 January 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. AVANT, Vol. IX, No. 3/2018 ISSN: 2082-6710 avant.edu.pl/en DOI: 10.26913/avant.2018.03.05 The Burden of Choice, the Complexity of the World and Its Reduction: The Game of Go/Weiqi as a Practice of “Empirical Metaphysics” Andrzej W. Nowak Institute of Philosophy Adam Mickiewicz Univesity in Poznań, Poland andrzej.w.nowak @ gmail.com Received 27 October 2018, accepted 28 November 2018, published in the winter 2018/2019. Abstract The main aim of the text is to show how a game of Go (Weiqi, baduk, Igo) can serve as a model representation of the ontological-metaphysical aspect of the actor–network theory (ANT). An additional objective is to demonstrate in return that this ontological-meta- physical aspect of ANT represented on Go/Weiqi game model is able to highlight the key aspect of this theory—onto-methodological praxis. -

FUEGO—An Open-Source Framework for Board Games and Go Engine Based on Monte Carlo Tree Search Markus Enzenberger, Martin Müller, Broderick Arneson, and Richard Segal

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL INTELLIGENCE AND AI IN GAMES, VOL. 2, NO. 4, DECEMBER 2010 259 FUEGO—An Open-Source Framework for Board Games and Go Engine Based on Monte Carlo Tree Search Markus Enzenberger, Martin Müller, Broderick Arneson, and Richard Segal Abstract—FUEGO is both an open-source software framework with new algorithms that would not be possible otherwise be- and a state-of-the-art program that plays the game of Go. The cause of the cost of implementing a complete state-of-the-art framework supports developing game engines for full-information system. Successful previous examples show the importance of two-player board games, and is used successfully in a substantial open-source software: GNU GO [19] provided the first open- number of projects. The FUEGO Go program became the first program to win a game against a top professional player in 9 9 source Go program with a strength approaching that of the best Go. It has won a number of strong tournaments against other classical programs. It has had a huge impact, attracting dozens programs, and is competitive for 19 19 as well. This paper gives of researchers and hundreds of hobbyists. In Chess, programs an overview of the development and current state of the UEGO F such as GNU CHESS,CRAFTY, and FRUIT have popularized in- project. It describes the reusable components of the software framework and specific algorithms used in the Go engine. novative ideas and provided reference implementations. To give one more example, in the field of domain-independent planning, Index Terms—Computer game playing, Computer Go, FUEGO, systems with publicly available source code such as Hoffmann’s man-machine matches, Monte Carlo tree search, open source soft- ware, software frameworks.