Right Place, Right Time: an Informal Memoir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Life Stories an Oral History of British

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES AN ORAL HISTORY OF BRITISH SCIENCE Professor Bob Dickson Interviewed by Dr Paul Merchant C1379/56 © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk This interview and transcript is accessible via http://sounds.bl.uk . © The British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB United Kingdom +44 (0)20 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators. © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk British Library Sound Archive National Life Stories Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref no: C1379/56 Collection title: An Oral History of British Science Interviewee’s surname: Dickson Title: Professor Interviewee’s forename: Bob Sex: Male Occupation: oceanographer Date and place of birth: 4th December, 1941, Edinburgh, Scotland Mother’s occupation: Housewife , art Father’s occupation: Schoolmaster teacher (part time) [chemistry] Dates of recording, Compact flash cards used, tracks [from – to]: 9/8/11 [track 1-3], 16/12/11 [track 4- 7], 28/10/11 [track 8-12], 14/2/13 [track 13-15] Location of interview: CEFAS [Centre for Environment, Fisheries & Aquaculture Science], Lowestoft, Suffolk Name of interviewer: Dr Paul Merchant Type of recorder: Marantz PMD661 Recording format : 661: WAV 24 bit 48kHz Total no. -

The History Group's Silver Jubilee

History of Meteorology and Physical Oceanography Special Interest Group Newsletter 2, 2009 A VIEW FROM THE CHAIR arranges meetings which are full of interest. We need especially to convince students that the The following review of 2008, by the Group’s origins and growth of the atmospheric and Chairman, Malcolm Walker, was presented at oceanic sciences are not only fascinating but the History Group’s Annual General Meeting also important. All too many research students on 28 March 2009. are now discouraged from reading anything Without an enthusiastic and conscientious more than ten years old and, moreover, do not committee, there would be no History Group. My appear to want to read anything that is not on thanks to all who have served on the committee the Web. To this end, historians of science are this past year. Thanks especially to our fighting back. A network of bodies concerned Secretary, Sara Osman, who has not only with the history of science, technology, prepared the paperwork for committee meetings mathematics, engineering and medicine has and written the minutes but also edited and been formed and our Group is one of the produced the newsletter (and sent you network’s members. An issue taken up by the subscription reminders!). She left the Met Office network during the past year is the withdrawal of in January 2008 and has since worked in the Royal Society funding from the National library of Kingston University. Unfortunately, she Cataloguing Unit for the Archives of now wishes to relinquish the post of Secretary Contemporary Scientists, which is based in the and is stepping down after today’s meeting. -

Journal of Marine Research, Sears Foundation for Marine Research

The Journal of Marine Research is an online peer-reviewed journal that publishes original research on a broad array of topics in physical, biological, and chemical oceanography. In publication since 1937, it is one of the oldest journals in American marine science and occupies a unique niche within the ocean sciences, with a rich tradition and distinguished history as part of the Sears Foundation for Marine Research at Yale University. Past and current issues are available at journalofmarineresearch.org. Yale University provides access to these materials for educational and research purposes only. Copyright or other proprietary rights to content contained in this document may be held by individuals or entities other than, or in addition to, Yale University. You are solely responsible for determining the ownership of the copyright, and for obtaining permission for your intended use. Yale University makes no warranty that your distribution, reproduction, or other use of these materials will not infringe the rights of third parties. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Journal of Marine Research, Sears Foundation for Marine Research, Yale University PO Box 208118, New Haven, CT 06520-8118 USA (203) 432-3154 fax (203) 432-5872 [email protected] www.journalofmarineresearch.org The subtropical recirculation of Mode Waters by Michael S. McCartney1 ABSTRACT A "Mode Water" is a particular type of water mass characterized by its vertical homogeneity. -

In Pdf Format

COLD WIND TWO GYRES A Tribute To VAL WORTHINGTON by a few of his friends in honor of his forty-one years of activity in oceanography Publication costs for this supplementary issue have been subsidized by the National Science Foundation, by the Office of Naval Research, and by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Printed in U.S.A. for the Sears Foundation for Marine Research, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, 06520, U.S.A. Van Dyck Printing Company, North Haven, Connecticut, 06473, U.S.A. EDITORIAL PREFACE Val Worthington has worked in oceanography for forty-one years. In honor of his long career, and on the occasion of his sixty-second birthday and retirement from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, we offer this collection of forty-one papers by some of his friends. The subtitle for the volume, “Cold Wind- Two Gyres,” is a free translation of his Japanese nickname, given him by Hideo Kawai and Susumu Honjo. It refers to two of his more controversial interpretations of the general circulation of the North Atlantic. The main emphasis of the collection is physical oceanography; in particular the general circulation of "his ocean," the North Atlantic (ten papers). Twenty-nine papers deal with physical oceanographic studies in other regions, modeling and techniques. There is one paper on the “Worthington effect” in paleo oceanography and one on fishes – this last being a topic dear to Val's heart, but one on which his direct influence has been mainly on population levels in Vineyard Sound. Many more people would like to have contributed to the volume but were prevented by the tight time table, the editorial and referee process, or the paper limit of forty-one. -

NEWSLETTER March 1982 WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION

NEWSLETTER March 1982 WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION WHOI MICROBIOLOGIST WINS FISHER AWARD Senior Scientist Holger Jannasch of the Biology Department has been chosen the 1982 r~cipient of the Fisher Scientific Comp3ny Award for Applied and Environmental Microbiology. The award is given to s timulate research and development in these fields and consists of a plaque and $1,000, which was presented to Holger early this month at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology (ASH) in Atlanta. In announcing Holger's selection for the Fisher Award, the ASH stated: "For th~ past 20 years Holger Jannasch has maintained an inventive program of research devoted to the quantitative understanding of the occurrence and metabolism of bacteria in the marine environment and their role within the complex matrix of assimilatory and dissimilatory transformations that found the marine food chain. His r esearch in mi crobial activity has been strongly based in the :NSTITUTION SCIENTIST WINS HONORS laboratory, where the elucidation o f 0F A DIFFERENT SORr! fundamental principles has permitted intelligent and meaningful direction for Senior Scientist Dave Ross of the quantitative s tudies in the field." :eology and Geophysics Department brought a The Society also noted his work on rather unusual honor to the Institution microbiology at hydrothermal vents : "Dr. 'ecently when he was named "best poker Jannasch is a t the forefront of research in llaye r on Cape Cod ." Dave was one of 100 the ecology and metabolism of the micro individuals to participate In an e limination organisms driving this unique ecosystem. He ~ournament February 26-27 at the Sheraton possesses not only the ingenuity but also a lnn, Falmouth, sponsored by the Falmouth ca r eful systematic approach to science that ~ions Club. -

Chapter 9 Physics Alumni 1851–1961

Chapter 9 Physics Alumni 1851–1961 Students 1871–76 The first student to graduate with a Victoria University (Owens College) degree in physics was Albert Griffiths in 1890. From 1867 until 1890, students registered for full time or part time courses and in some cases, proceeded to study for degree courses elsewhere. Schuster’s colleagues [6] listed some of the past students who had been connected with the Physical Laboratories, admitting that the list was not complete. 1867–72 John Henry Poynting 1868–70 Ernest Howard Griffiths 1871–76 Joseph John Thomson 1884–87 Charles Thomson Rees Wilson 1879–81 William Stroud 1880–82 Henry Stroud 1875–77 Arthur Mason Worthington Graduates 1890–1951 & Student group Photographs The degrees of PhD and DSc were first introduced in Manchester in 1918 and it was the norm before this time and for a period thereafter, for BSc 748 graduates to follow up with a one year MSc course. 1890 First Class: Albert Griffiths. Third Class: Ernest Edward Dentith Davies. Albert Griffiths Assoc. Owens 1890, MSc 1893, DSc 1899. After graduating, Albert Griffiths was a research student, fellow, demonstrator and lecturer at Owens between 1892 and 1898, in between posts at Freiburg, Southampton and Sheffield. He became Head of the Physics Department at Birkbeck in 1900. E E D Davies, born on the Isle of Man, obtained a BSc in mathematics in 1889, an MSc in 1892, a BA in 1893 before becoming a Congregational Minister in 1895. Joseph Thompson lists him [246], as a student at the Lancashire Independent College in 1893. -

Book Reviews

book reviews Crop Yields and Climate Change to the Year 2000, Volume I. By the questionable record in facing up to regional droughts with that tech- Research Directorate of the National Defense University. 1980. nology. While the study does consider a spectrum of annual cli- 128 pages, n.p. Paperbound. U.S. Government Printing Office, mates, it does not consider runs of extreme years which often lead to Washington, D.C. serious regional droughts and economic upsets. The elements of the report are well prepared and presented, but This innovative work will interest a wide audience, particularly their assembly and frequent references to important materials in among those concerned with the future capability of the world's other volumes tend to break reading continuity. A foreword, ab- agriculture to meet changing societal needs and changing climates. stract, preface, and summary precede the chapters of the report. The report is identified as the second phase of a climate impact Each is well done, and collectively they provide the setting for this assessment. Its purpose is to show how major world crop yields volume and help serve the dichotomous readership for which the re- would be affected by specified climate changes, assuming constant port is intended. The preface and summary state the problem, back- agricultural technology. It is a companion study to others which as- ground methodology, and results in a manner that will interest sess the nature of possible climate changes and the policy implica- policy-oriented and general readers. The ensuing chapters are more tions of related altered productivity. The combined effort is a sig- technical, detailing methodology, technology, and yields obtained nificant contribution to the development of impact assessment for different scenarios as model output. -

De Morgan Association NEWSLETTER

UCL DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS NEWSLETTER 2016/17 De Morgan Association NEWSLETTER UCL Mathematics Department The department is proud to recruit excellent in which a departments’ teaching and learning undergraduate students who, having typically provision are reviewed every 5-7 years. A team of achieved A*A*A at A-level (with the A*s in assessors visited the department early 2016 and Mathematics and Further Mathematics), are conducted a thorough review of our teaching- among the highest qualified entering UCL. That related practices and met with both students we do so in large numbers, annually recruiting a and staff. The IQR team reported that “overall first year cohort in excess of 200 students to our Mathematics operated effectively in delivering undergraduate programmes, is impressive and high quality undergraduate and postgraduate also makes the department one of the largest programmes as demonstrated by the design of at UCL in terms of numbers of undergraduate its programmes, its responsiveness to industry, students. and the high levels of satisfaction expressed by staff and students.’’ To sustain such large numbers of well-qualified students it is important that the department The IQR highlighted several items of good teaches well. This means many things of practice including our commitment to both course e.g. presenting mathematics clearly and student transition to higher education thoroughly, even inspiringly, in lectures; providing and to widening participation. The Undergraduate timely and useful feedback; offering a broad Colloquium was also singled out for praise. range of mathematically interesting modules In this activity, undergraduate students, with and projects; and providing effective support for support from the department, arrange their own students. -

North Atlantic's Transformation Pipeline Chills and Redistributes

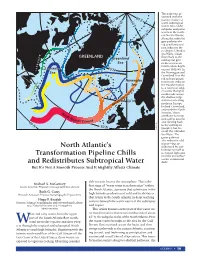

The pathways as- 60˚E sociated with the 30˚E transformation of 60˚W warm subtropical waters into colder 30˚W subpolar and polar waters in the north- ern North Atlantic. 80˚N Along the subpolar gyre pathway the red to yellow transi- tion indicates the cooling to Labrador Sea Water, which R GREENLAND flows back to the Greenland subtropical gyre Sea in the west as an intermediate depth Labrador 70˚N current (yellow). In L A B R A D O Sea the Norwegian and N Greenland Seas the EW FO U N red to blue/purple D LA N Norwegian D transitions indicate Sea the transformation t to a variety of cold- n e er waters that spill rr u southwards across C n the shallow ridge ia eg 60˚N system connecting rw northern Europe, No Iceland, Greenland, and northern North America. These No rth overflows form up A into a deep current tlant 40˚N ic Current IRELAND also flowing back 50˚N to the subtropics Jack Cook (purple), but be- neath the Labrador Sea Water. The green pathway also indicates cold waters—but so North Atlantic’s influenced by con- tinental runnoff as to remain light and Transformation Pipeline Chills near the sea surface on the continental and Redistributes Subtropical Water shelf. But It’s Not A Smooth Process And It Mightily Affects Climate able oceanic heat to the atmosphere. This is the Michael S. McCartney Senior Scientist, Physical Oceanography Department first stage of “warm water transformation” within the North Atlantic, a process that culminates in the Ruth G. -

V22n04 1981-04To05.Pdf (1.266Mb)

, • ] i• • i NEWSLETTER " ." April- May 1981 WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION WOMEN ' S COMM ITTEE TO SPONSOR CAREER WORKSHOP The WHOI Women's Committee is planning to sponsor a Women in Science Career Work shop in October to introduce advanced high school , undergraduate and graduate women students to the diversity of career options available in the ocean sciences. The one-day workshop will include an opening address by Evelyn Murphy, former Massachusetts Secretary for Environmental Affairs now at MIT, and eight morning and afternoon panel s representing the various scientific disciplines and supporting fields in ocean science. As part of the workshop activity the Women's Committee is also planning to develop an audio-visual program depicting women employed at all levels in oceanog raphy. The program will be made available to high schools, colleges , and other career placement services. It wasn't all that long ago that ASTERIAS HOUSING OFFICE NEEDS LISTINGS had problems getting through the ice in Eel Pond channel to her berth near Red The Housing Office needs listings of field. This photo, by Shelley Lauzon , was houses, apartments , rooms, etc. for the taken in late January. many fellows and students who will be re Siding here during the summer season. If you have suitable accommodations available, ?HYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHY DEPARTMENT contact the Hou sing Office , ext. 2215 . CHAIRMAN APPOINTED Director John Steele announced April ASSOCIATES ' DINNERS PLANNED 15 the appointment of Nick Fofonoff as Physical oceanography Department Chairman. Former ambassador and Cabinet member ~ick will succeed Val Worthington in Novem Elliot Richardson was the guest speaker )er. -

The Jesus College Record 2017

RECORD 2017 CONTENTS FROM THE EDITOR 3 THE PRINCIPAL’S REPORT 7 FELLOWS AND COLLEGE LECTURERS 18 NON-ACADEMIC STAFF 27 FELLOWS’ AND LECTURERS’ NEWS 30 THE FOWLER LECTURE 2018 38 A GEOGRAPHER AT JESUS 40 WRITING COLLEGE HISTORY 48 JESUS COLLEGE AND GUERNSEY 54 IN MEMORIAM – JEREMY DICKSON 58 UBU TRUMP 62 A TRIBUTE TO CHARLOTTE ‘LOTTIE’ FULLERTON 64 TRAVEL AWARDS REPORTS 66 TRAVEL AWARDS 74 THE COLLEGE’S CHINA ROOTS 76 A TRIBUTE TO JOHN BURROW 86 FRANK HELIER: THE OTHER LAWRENCE 90 F FOR FACSIMILE 94 GOOD TIMES: REMEMBERING RAYMOND HIDE 100 COLLEGE PEOPLE – THE CATERING TEAM 104 A YEAR IN ACCESS 107 A YEAR IN THE JCR 109 A YEAR IN THE MCR 111 A YEAR IN DEVELOPMENT 113 A YEAR IN CHAPEL 116 SPORTS REPORTS 120 PRIZES, AWARDS & ELECTIONS 127 DOCTORATES AWARDED 135 OLD MEMBERS’ OBITUARIES AND MEMORIAL NOTICES 138 SELECTED PUBLICATIONS 167 HONOURS, AWARDS AND QUALIFICATIONS 173 APPOINTMENTS, BIRTHS, MARRIAGES, IN MEMORIAM 175 USEFUL INFORMATION 181 2 FROM THE EDITOR PROFESSOR ARMAND D’ANGOUR There was a young man who said “God Must find it exceedingly odd To think that the tree Should continue to be When there’s no one about in the quad.” Esse est percipi – ‘to exist is to be perceived’ – sums up the empiri- cist philosophy of Bishop George Berkeley (1685-1753), whose name is now perhaps most famil- iar (and, I learn, pronounced in its original manner, ‘Bark-’ being a later English affectation) from the university in California named after him. Berkeley argued that things have being only insofar as they are perceived; the above limerick, allegedly penned by a Balliol undergraduate, sums up Photo: Ander McIntyre. -

Stanley Keith Runcorn FRS ( 1922-1995)

Catalogue of the papers and correspondence of Stanley Keith Runcorn FRS ( 1922-1995) VOLUME I General Introduction Section A: Biographical Section B: University of Manchester Section C: University of Newcastle Section D: Research Section E: Publications Section F: Lectures by Timothy E. Powell and Caroline Thibeaud NCUACS catalogue no. 104/3/02 S.K. Runcorn NCUACS 104/3/02 Title: Catalogue of the papers and correspondence of Stanley Keith Runcorn FRS (1922-1995), geophysicist Compiled by: Timothy E. Powel! and Peter Harper Description level: Fonds Date of material: 1936-1995 Extent of material: 100 boxes, ca 2,800 items Deposited in: College Archives, Imperial College London Reference code: GB 0098 B/RUNCORN © 2002 National Cataloguing Unit for the Archives of Contemporary Scientists, University of Bath. NCUACS catalogue no. 104/3/02 S.K. Runcorn 2 NCUACS 104/3/02 The work of the National Cataloguing Unit for the Archives of Contemporary Scientists, and the production of this catalogue, are made possible by the support of the following societies and organisations: Friends of the Center for History of Physics, American Institute of Physics The British Computer Society The British Crystallographic Association The Geological Society The Institute of Physics The Royal Society The Royal Astronomical Society The Royal Society of Chemistry The Wellcome Trust S.K. Runcorn 3 NCUACS 104/3/02 NOT ALL THE MATERIAL IN THIS COLLECTION MAY YET BE AVAILABLE FOR CONSULTATION. ENQUIRIES SHOULD BE ADDRESSED IN THE FIRST INSTANCE TO: THE COLLEGE ARCHIVIST