WHOI After the Big Ships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Life Stories an Oral History of British

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES AN ORAL HISTORY OF BRITISH SCIENCE Professor Bob Dickson Interviewed by Dr Paul Merchant C1379/56 © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk This interview and transcript is accessible via http://sounds.bl.uk . © The British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB United Kingdom +44 (0)20 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators. © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk British Library Sound Archive National Life Stories Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref no: C1379/56 Collection title: An Oral History of British Science Interviewee’s surname: Dickson Title: Professor Interviewee’s forename: Bob Sex: Male Occupation: oceanographer Date and place of birth: 4th December, 1941, Edinburgh, Scotland Mother’s occupation: Housewife , art Father’s occupation: Schoolmaster teacher (part time) [chemistry] Dates of recording, Compact flash cards used, tracks [from – to]: 9/8/11 [track 1-3], 16/12/11 [track 4- 7], 28/10/11 [track 8-12], 14/2/13 [track 13-15] Location of interview: CEFAS [Centre for Environment, Fisheries & Aquaculture Science], Lowestoft, Suffolk Name of interviewer: Dr Paul Merchant Type of recorder: Marantz PMD661 Recording format : 661: WAV 24 bit 48kHz Total no. -

Journal of Marine Research, Sears Foundation for Marine Research

The Journal of Marine Research is an online peer-reviewed journal that publishes original research on a broad array of topics in physical, biological, and chemical oceanography. In publication since 1937, it is one of the oldest journals in American marine science and occupies a unique niche within the ocean sciences, with a rich tradition and distinguished history as part of the Sears Foundation for Marine Research at Yale University. Past and current issues are available at journalofmarineresearch.org. Yale University provides access to these materials for educational and research purposes only. Copyright or other proprietary rights to content contained in this document may be held by individuals or entities other than, or in addition to, Yale University. You are solely responsible for determining the ownership of the copyright, and for obtaining permission for your intended use. Yale University makes no warranty that your distribution, reproduction, or other use of these materials will not infringe the rights of third parties. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Journal of Marine Research, Sears Foundation for Marine Research, Yale University PO Box 208118, New Haven, CT 06520-8118 USA (203) 432-3154 fax (203) 432-5872 [email protected] www.journalofmarineresearch.org The subtropical recirculation of Mode Waters by Michael S. McCartney1 ABSTRACT A "Mode Water" is a particular type of water mass characterized by its vertical homogeneity. -

In Pdf Format

COLD WIND TWO GYRES A Tribute To VAL WORTHINGTON by a few of his friends in honor of his forty-one years of activity in oceanography Publication costs for this supplementary issue have been subsidized by the National Science Foundation, by the Office of Naval Research, and by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Printed in U.S.A. for the Sears Foundation for Marine Research, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, 06520, U.S.A. Van Dyck Printing Company, North Haven, Connecticut, 06473, U.S.A. EDITORIAL PREFACE Val Worthington has worked in oceanography for forty-one years. In honor of his long career, and on the occasion of his sixty-second birthday and retirement from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, we offer this collection of forty-one papers by some of his friends. The subtitle for the volume, “Cold Wind- Two Gyres,” is a free translation of his Japanese nickname, given him by Hideo Kawai and Susumu Honjo. It refers to two of his more controversial interpretations of the general circulation of the North Atlantic. The main emphasis of the collection is physical oceanography; in particular the general circulation of "his ocean," the North Atlantic (ten papers). Twenty-nine papers deal with physical oceanographic studies in other regions, modeling and techniques. There is one paper on the “Worthington effect” in paleo oceanography and one on fishes – this last being a topic dear to Val's heart, but one on which his direct influence has been mainly on population levels in Vineyard Sound. Many more people would like to have contributed to the volume but were prevented by the tight time table, the editorial and referee process, or the paper limit of forty-one. -

NEWSLETTER March 1982 WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION

NEWSLETTER March 1982 WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION WHOI MICROBIOLOGIST WINS FISHER AWARD Senior Scientist Holger Jannasch of the Biology Department has been chosen the 1982 r~cipient of the Fisher Scientific Comp3ny Award for Applied and Environmental Microbiology. The award is given to s timulate research and development in these fields and consists of a plaque and $1,000, which was presented to Holger early this month at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology (ASH) in Atlanta. In announcing Holger's selection for the Fisher Award, the ASH stated: "For th~ past 20 years Holger Jannasch has maintained an inventive program of research devoted to the quantitative understanding of the occurrence and metabolism of bacteria in the marine environment and their role within the complex matrix of assimilatory and dissimilatory transformations that found the marine food chain. His r esearch in mi crobial activity has been strongly based in the :NSTITUTION SCIENTIST WINS HONORS laboratory, where the elucidation o f 0F A DIFFERENT SORr! fundamental principles has permitted intelligent and meaningful direction for Senior Scientist Dave Ross of the quantitative s tudies in the field." :eology and Geophysics Department brought a The Society also noted his work on rather unusual honor to the Institution microbiology at hydrothermal vents : "Dr. 'ecently when he was named "best poker Jannasch is a t the forefront of research in llaye r on Cape Cod ." Dave was one of 100 the ecology and metabolism of the micro individuals to participate In an e limination organisms driving this unique ecosystem. He ~ournament February 26-27 at the Sheraton possesses not only the ingenuity but also a lnn, Falmouth, sponsored by the Falmouth ca r eful systematic approach to science that ~ions Club. -

Book Reviews

book reviews Crop Yields and Climate Change to the Year 2000, Volume I. By the questionable record in facing up to regional droughts with that tech- Research Directorate of the National Defense University. 1980. nology. While the study does consider a spectrum of annual cli- 128 pages, n.p. Paperbound. U.S. Government Printing Office, mates, it does not consider runs of extreme years which often lead to Washington, D.C. serious regional droughts and economic upsets. The elements of the report are well prepared and presented, but This innovative work will interest a wide audience, particularly their assembly and frequent references to important materials in among those concerned with the future capability of the world's other volumes tend to break reading continuity. A foreword, ab- agriculture to meet changing societal needs and changing climates. stract, preface, and summary precede the chapters of the report. The report is identified as the second phase of a climate impact Each is well done, and collectively they provide the setting for this assessment. Its purpose is to show how major world crop yields volume and help serve the dichotomous readership for which the re- would be affected by specified climate changes, assuming constant port is intended. The preface and summary state the problem, back- agricultural technology. It is a companion study to others which as- ground methodology, and results in a manner that will interest sess the nature of possible climate changes and the policy implica- policy-oriented and general readers. The ensuing chapters are more tions of related altered productivity. The combined effort is a sig- technical, detailing methodology, technology, and yields obtained nificant contribution to the development of impact assessment for different scenarios as model output. -

North Atlantic's Transformation Pipeline Chills and Redistributes

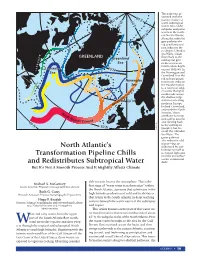

The pathways as- 60˚E sociated with the 30˚E transformation of 60˚W warm subtropical waters into colder 30˚W subpolar and polar waters in the north- ern North Atlantic. 80˚N Along the subpolar gyre pathway the red to yellow transi- tion indicates the cooling to Labrador Sea Water, which R GREENLAND flows back to the Greenland subtropical gyre Sea in the west as an intermediate depth Labrador 70˚N current (yellow). In L A B R A D O Sea the Norwegian and N Greenland Seas the EW FO U N red to blue/purple D LA N Norwegian D transitions indicate Sea the transformation t to a variety of cold- n e er waters that spill rr u southwards across C n the shallow ridge ia eg 60˚N system connecting rw northern Europe, No Iceland, Greenland, and northern North America. These No rth overflows form up A into a deep current tlant 40˚N ic Current IRELAND also flowing back 50˚N to the subtropics Jack Cook (purple), but be- neath the Labrador Sea Water. The green pathway also indicates cold waters—but so North Atlantic’s influenced by con- tinental runnoff as to remain light and Transformation Pipeline Chills near the sea surface on the continental and Redistributes Subtropical Water shelf. But It’s Not A Smooth Process And It Mightily Affects Climate able oceanic heat to the atmosphere. This is the Michael S. McCartney Senior Scientist, Physical Oceanography Department first stage of “warm water transformation” within the North Atlantic, a process that culminates in the Ruth G. -

V22n04 1981-04To05.Pdf (1.266Mb)

, • ] i• • i NEWSLETTER " ." April- May 1981 WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION WOMEN ' S COMM ITTEE TO SPONSOR CAREER WORKSHOP The WHOI Women's Committee is planning to sponsor a Women in Science Career Work shop in October to introduce advanced high school , undergraduate and graduate women students to the diversity of career options available in the ocean sciences. The one-day workshop will include an opening address by Evelyn Murphy, former Massachusetts Secretary for Environmental Affairs now at MIT, and eight morning and afternoon panel s representing the various scientific disciplines and supporting fields in ocean science. As part of the workshop activity the Women's Committee is also planning to develop an audio-visual program depicting women employed at all levels in oceanog raphy. The program will be made available to high schools, colleges , and other career placement services. It wasn't all that long ago that ASTERIAS HOUSING OFFICE NEEDS LISTINGS had problems getting through the ice in Eel Pond channel to her berth near Red The Housing Office needs listings of field. This photo, by Shelley Lauzon , was houses, apartments , rooms, etc. for the taken in late January. many fellows and students who will be re Siding here during the summer season. If you have suitable accommodations available, ?HYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHY DEPARTMENT contact the Hou sing Office , ext. 2215 . CHAIRMAN APPOINTED Director John Steele announced April ASSOCIATES ' DINNERS PLANNED 15 the appointment of Nick Fofonoff as Physical oceanography Department Chairman. Former ambassador and Cabinet member ~ick will succeed Val Worthington in Novem Elliot Richardson was the guest speaker )er. -

Journal of Marine Research, Sears Foundation for Marine Research, Yale University PO Box 208118, New Haven, CT 06520-8118 USA (2

The Journal of Marine Research is an online peer-reviewed journal that publishes original research on a broad array of topics in physical, biological, and chemical oceanography. In publication since 1937, it is one of the oldest journals in American marine science and occupies a unique niche within the ocean sciences, with a rich tradition and distinguished history as part of the Sears Foundation for Marine Research at Yale University. Past and current issues are available at journalofmarineresearch.org. Yale University provides access to these materials for educational and research purposes only. Copyright or other proprietary rights to content contained in this document may be held by individuals or entities other than, or in addition to, Yale University. You are solely responsible for determining the ownership of the copyright, and for obtaining permission for your intended use. Yale University makes no warranty that your distribution, reproduction, or other use of these materials will not infringe the rights of third parties. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Journal of Marine Research, Sears Foundation for Marine Research, Yale University PO Box 208118, New Haven, CT 06520-8118 USA (203) 432-3154 fax (203) 432-5872 [email protected] www.journalofmarineresearch.org Low-frequency temperature fluctuations between Ocean Station Echo and Bermuda 1 1 by W. Sturges and Alan Summy , 2 ABSTRACT Hydrographic data at Ocean Station Echo (35N, 48W) form an almost continuous 6-year series ending in 1973. -

Circulation Oceanus REPORTS on RESEARCH at the WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION

REPORTS ON RESEARCH AT THE WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION Volume 37, Number 1 Spring 1994 Atlantic Ocean * .,' I Circulation Oceanus REPORTS ON RESEARCH AT THE WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION Vol. 37, No. 1 Spring 1994 ISSN 0029-8182 Atlantic Ocean Circulation The Atlantic Ocean 1 Progress in Describing and Interpreting Its Circulation By Michael S. McCartney A Primer on Ocean Currents 3 Mi'i'i^iiri'ii/fi/tK <niil Lin/in nfriii/xicn/ Oceanographers Towards a Model of Atlantic Ocean Circulation 5 The Plumbing of the Cl/ii/nlr's Rnil/u/m- : By MichaelS. Mri''nrli/i // Dynamics and Modeling of Marginal Sea Outflows 9 Out They Go, Doini, and Around tin' \\brlil By James F. Price Meddies, Eddies, Floats, and Boats 12 1 How Do Mediterranean ni/d Atlantic Waters .l/ii .-' By Amy Bower Where Currents Cross 16 Interarlnni the and the Western Current t CiilfSln'am >i i nuii'< is published semi-annually by the Woods Hole of Deep Boundary Rolinl S. P/,i;iil Oceanographic Institution. Woods Hole. MA (C~i4:i By 508-457-2 i.cxi 271H Giant Eddies of South Atlantic Water Invade the North 19 iii-ciniiix and its logo are Registered Trademarks ol the Woods Hole Oceanographio Institution, All Rights Reserved Disrupted Flou- andSwiriing H'ati'n By Philip L Richardann In North America, an Oceanns Package. including<Vivj//.s magazine, Woods Hole Currents la l^-pagc tabloid-size The Deep Basin Experiment 22 1 ) .mil 1,; nu i ( neusletiei l-:.i/ilnr, an 8-page junior-high-selnm! How Does the \\'<iii-i F/<>/i in tin' l>,r/> Si</ith Mini/tie? educational publu :iin.n ) IN axailable for a sj.'i in In- Single Nelson Hogg I By ilples lit Drvr/HI/.v rust M 1)11 pills S| Illl shipping Outside \iirth America, the annual fee fur fii-fniiin, uK is S:;ii. -

Journal of Marine Research, Sears Foundation For

The Journal of Marine Research is an online peer-reviewed journal that publishes original research on a broad array of topics in physical, biological, and chemical oceanography. In publication since 1937, it is one of the oldest journals in American marine science and occupies a unique niche within the ocean sciences, with a rich tradition and distinguished history as part of the Sears Foundation for Marine Research at Yale University. Past and current issues are available at journalofmarineresearch.org. Yale University provides access to these materials for educational and research purposes only. Copyright or other proprietary rights to content contained in this document may be held by individuals or entities other than, or in addition to, Yale University. You are solely responsible for determining the ownership of the copyright, and for obtaining permission for your intended use. Yale University makes no warranty that your distribution, reproduction, or other use of these materials will not infringe the rights of third parties. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Journal of Marine Research, Sears Foundation for Marine Research, Yale University PO Box 208118, New Haven, CT 06520-8118 USA (203) 432-3154 fax (203) 432-5872 [email protected] www.journalofmarineresearch.org Weakly depth-dependent segments -

Informal Memoir. a Working Draft

1 Informal Memoir. A Working Draft 2 Carl Wunsch∗ Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences Harvard University Cambridge MA 02138 email: [email protected] 3 August 26, 2021 4 1Introductory 1 5 This sketch memoir was originally stimulated by a podcast interview of me by Michael White 6 (16 May 2018), geoscience editor of Nature. He asked some questions about my life and career 7 that I hadn’t thought would interest anyone else. But I then thought to record them in writing 8 before my memory goes altogether. If anyone feels obligated to write a memorial of my work, 9 maybe it will be of some assistance. As an overview, my life is almost a cliche of the story of 10 Jewish immigrants to the US circa 1900, and their striving for success via their children and 11 grandchildren in the professions, academic, and otherwise. An earlier, condensed, version of 12 this memoir was published by Annual Review of Marine Science (2021). At best, much of what 13 follows will likely be of interest only to my immediate family. To some extent, my life has 14 been boringly simple: I’ve had one wife, one job, two rewarding children, and apart from short 15 intervals such as sabbaticals, have lived for over 60 years in one city. 16 Parents 17 My parents were both the children of recent immigrants. My mother, Helen Gellis, was 18 born in 1910 Dover NJ the daughter of Morris Gellis and Minnie Bernstein Gellis who had 19 emigrated from near Vilna, Lithuania and near Minsk in White Russia respectively around 20 1908. -

V15n06 1974-06.Pdf

P-s- ... /(' 0 '" ~ :z: '".... NEWSLETTER ..... '" c: Volume 15 Number 6 0 ,... "0 June 1974 ~ ~ 1930 WORTHINGTON NAMED NEW CHAIRMAN TRUSTEES AND CORPORATION TO MEET, OF PHYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHY DEPARTMENT ESL TO BE DEDICATED ON JUNE 20 Val Worthington has been named chairman of the Dedication of the Environmental Systems Laboratory Physical Oceanography Department. He has been (ESL) on the Quisseti Campus is sched uled for June 20 associated with the Institution, except for three years in at 2:30 p.m. to coincide with the meeting day of the the Navy, since 194 1. Institution Corporation and Trustees. An open house Worthington succeeds Ferris Webster, who was for Oceanographic employees will follow the dedication. appointed Associate Director for Research last spring Shuttle buses to ESL will run from the School street and has bee n filling both positions since then. side of Redfield Building beginn ing at 1: 45 p.m. Worthington studied at Princeton University from Dedication speaker will be Athelstan Spilhaus, mete 1938 to 1941 when he came to the Institution as a orologist, oceanographer, NOAA consultant, former technician, but he is a member of the Society of stafT member and current member of the W.H.O.l. Subprofessional Oceanographers. an exclusive organ· Corporation. He is also the inventor of the bathy ization with membership limited to oceanographers who thermograph and the Spilhaus space clock. have " limited educational qualifications". (The other members are Fritz Fuglister and Hank Stommel. ) Degree or not, Worthington is a respected ocean ••• OCEANOGRAPHIC SHIP NOTES ••• ographer, who is well -known particularly for work on Atl antic circulati on.