The Engine Immobilizer: a Non-Starter for Car Thieves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citroën Berlingo

CITROËN BERLINGO (MF) 1.9 D (MFWJZ) 07.98 - 10.05 51 70 1868 4 CITROËN BERLINGO (MF) 1.9 D 4WD (MFWJZ) 07.98 - 51 69 1868 4 CITROËN BERLINGO karoserie (M_) 1.9 D 70 04.99 - 51 69 1868 4 (MBWJZ, MCWJZ) CITROËN BERLINGO karoserie (M_) 1.9 D 70 4WD 07.98 - 51 69 1868 4 (MBWJZ, MCWJZ) CITROËN BERLINGO karoserie (M_) 2.0 HDI 90 12.99 - 66 90 1997 4 (MBRHY, MCRHY) CITROËN BERLINGO karoserie (M_) 2.0 HDI 90 4WD 11.00 - 66 90 1997 4 (MBRHY, MCRHY) CITROËN C5 I (DC_) 2.0 HDi (DCRHYB) 03.01 - 08.04 66 90 1997 4 CITROËN C5 I (DC_) 2.0 HDi 03.01 - 08.04 79 107 1997 4 CITROËN C5 I (DC_) 2.0 HDi (DCRHZB, DCRHZE) 03.01 - 08.04 80 109 1997 4 CITROËN C5 I (DC_) 2.0 HDi (DCRHZB, DCRHZE) 06.01 - 08.04 80 109 1997 4 CITROËN C5 I (DC_) 2.2 HDi (DC4HXB, DC4HXE) 03.01 - 08.04 98 133 2179 4 CITROËN C5 I Break (DE_) 2.0 HDi (DERHYB) 06.01 - 08.04 66 90 1997 4 CITROËN C5 I Break (DE_) 2.0 HDi (DERHSB, 06.01 - 08.04 79 107 1997 4 DERHSE) CITROËN C5 I Break (DE_) 2.0 HDi 06.01 - 08.04 80 109 1997 4 CITROËN C5 I Break (DE_) 2.2 HDi (DE4HXB, 06.01 - 08.04 98 133 2179 4 DE4HXE) CITROËN C5 II (RC_) 2.2 HDi (RC4HXE) 09.04 - 98 133 2179 4 CITROËN C5 II (RC_) 2.2 HDi (RC4HXE) 02.05 - 98 133 2179 4 CITROËN C5 II Break (RE_) 2.2 HDi (RE4HXE) 09.04 - 98 133 2179 4 CITROËN C5 II Break (RE_) 2.2 HDi (RE4HXE) 02.05 - 98 133 2179 4 CITROËN C8 (EA_, EB_) 2.0 HDi 07.02 - 79 107 1997 4 CITROËN C8 (EA_, EB_) 2.0 HDi 07.02 - 80 109 1997 4 CITROËN C8 (EA_, EB_) 2.2 HDi 07.02 - 94 128 2179 4 CITROËN C8 (EA_, EB_) 2.2 HDi 06.07 - 120 163 2179 4 CITROËN C8 (EA_, EB_) 2.2 HDi 06.06 - 125 -

Road & Track Magazine Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8j38wwz No online items Guide to the Road & Track Magazine Records M1919 David Krah, Beaudry Allen, Kendra Tsai, Gurudarshan Khalsa Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2015 ; revised 2017 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Road & Track M1919 1 Magazine Records M1919 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Road & Track Magazine records creator: Road & Track magazine Identifier/Call Number: M1919 Physical Description: 485 Linear Feet(1162 containers) Date (inclusive): circa 1920-2012 Language of Material: The materials are primarily in English with small amounts of material in German, French and Italian and other languages. Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36 hours in advance. Abstract: The records of Road & Track magazine consist primarily of subject files, arranged by make and model of vehicle, as well as material on performance and comparison testing and racing. Conditions Governing Use While Special Collections is the owner of the physical and digital items, permission to examine collection materials is not an authorization to publish. These materials are made available for use in research, teaching, and private study. Any transmission or reproduction beyond that allowed by fair use requires permission from the owners of rights, heir(s) or assigns. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Road & Track Magazine records (M1919). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. Note that material must be requested at least 36 hours in advance of intended use. -

![SUZUKI GOES Off [ROAD]!](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8806/suzuki-goes-off-road-488806.webp)

SUZUKI GOES Off [ROAD]!

SUZUKI AUTUMN 2007 AUTUMN NOW SX4 GOES OFF [ROAD]! CONGRATULATIONS CAMERON GIRLS’ DAY OUT EVENT SWIFT toPS AWards again FUNKY NEW JIMNY ltd 2 NEW dealersHIPS OPEN vitara DRIVE day NEAR YOU cover STORY More than just ‘a pretty face’ Motoring journalists around the country are raving about Suzuki’s newest kid on the block – the SX4. 2 “ThIS IS ONE HELL OF A GOOD LOOKING experience to the next level. This feature CAR. It has enough real 4WD cues in the particularly impressed motoring journalist styling to satisfy the macho image, but Rob Maetzig ‘…when road conditions get … combines a sedan look so it is also tight or unsealed, it is a breeze to flick into stylish. On looks alone, this is going to the automatic or locked AWD modes which be another winner for Suzuki. But there make the driving sensation even more is more to the SX4 than a pretty face.” secure. That’s what makes the new SX4 NZ Driver Magazine. something rather special’ Indeed, there is plenty of substance behind Forty-five leading motoring journalists from this very good-looking exterior. around the world also agree that the SX4 is rather special – as they have selected it The SX4 is offered standard with 4WD and as one of the top ten finalists in the 2007 a 2-litre petrol engine – similar to the World Car of the Year award. It is one of one in the Grand Vitara. There is a choice only two Japanese cars in the top ten – the of 5-speed manual transmission and an other is the Lexus LS 460. -

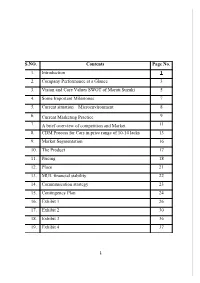

S.NO. Contents Page No. 1. Introduction 1 2. Company Performance at a Glance 3 3. Vision and Core Values SWOT of Maruti Suzuki 5 4

S.NO. Contents Page No. 1. Introduction 1 2. Company Performance at a Glance 3 3. Vision and Core Values SWOT of Maruti Suzuki 5 4. Some Important Milestones 7 5. Current situation – Microenvironment 8 6. Current Marketing Practice 9 7. A brief overview of competition and Market 11 8. CDM Process for Cars in price range of 10-14 lacks 13 9. Market Segmentation 16 10. The Product 17 11. Pricing 18 12. Place 21 13. MUL financial stability 22 14. Communication strategy 23 15. Contingency Plan 24 16. Exhibit 1 26 17. Exhibit 2 30 18. Exhibit 3 36 19. Exhibit 4 37 1 1. I NTRODUCTION Maruti Suzuki India Ltd. – Company Profile Maruti Suzuki India Ltd. (current logo) Maruti Udyog Ltd. (old logo) Maruti Suzuki is one of the leading automobile manufacturers of India, and is the leader in the car segment both in terms of volume of vehicle sold and revenue earned. It was established in February, 1981 as Maruti Udyog Ltd. (MUL), but actual production started in 1983 with the Maruti 800 (based on the Suzuki Alto kei car of Japan), which was the only modern car available in India at that time. Previously, the Government of India held a 18.28% stake in the company, and 54.2% was held by Suzuki of Japan. However, in June 2003, the Government of India held an initial public offering of 25%. By May 10, 2007 sold off its complete share to Indian financial institutions. Through 2004, Maruti Suzuki has produced over 5 million cars. Now, the company annually exports more than 50,000 cars and has an extremely large domestic market in India selling over 730,000 cars annually. -

Suzuki Swift Update

SUZUKI SWIFT UPDATE • Available in 10 colours with full personalisation options available for both SWIFT UPDATE exterior and interior trim. • Six airbags, Air conditioning, DAB Radio, privacy glass, LED daytime SUZUKI’S THIRD GENERATION running lights and Bluetooth fitted as standard on all new Swift models. • SZ-T adds smartphone link display audio, rear view camera, front fog lamps COMPACT SUPERMINI and 16-inch alloy wheels. • Attitude Special Edition model added in January 2019 based on SZ-T and with 1.2-litre Dualjet engine and unique exterior styling upgrades. • Third Generation Swift – on sale in the UK and Republic of Ireland since • SZ5 adds auto air conditioning, Navigation, LED headlamps, polished 16- June 2017. inch alloy wheels, rear electric windows, Dual Sensor Brake Support and • Available in SZ3, SZ-T, Attitude and SZ5 grades. Adaptive Cruise Control. • SZ5 available with ALLGRIP Auto 4WD system. • 111PS 1.0-litre three-cylinder Boosterjet turbo engine offers CO2 emissions of 110g/km (NEDC) and combined fuel consumption of 51.4mpg (WLTP). • 10 per cent lighter, 19 per cent more powerful and 8 per cent more fuel efficient than previous Swift model. • 90PS 1.2-litre four-cylinder Dualjet engine offers CO2 emissions of 106g/km (NEDC) and combined fuel consumption of 55.4mpg. (WLTP Regulation) • UK sales plan of more than 12,500 units in 2019 – 70,000 for Europe. • Boosterjet engine available with Suzuki’s SHVS hybrid system (Smart • Global Swift sales of 6.6 million units since 2005 Hybrid Vehicle by Suzuki) with CO2 emissions of 123g/km. (WLTP Regulation) • More than 1.1 million sales in Europe since 2005, 150,000 in the UK. -

VS20456 DIESEL ENGINE COMPRESSION TEST ADAPTOR SET Thank You for Purchasing a Sealey Product

Instructions for: VS20456 DIESEL ENGINE COMPRESSION TEST ADAPTOR SET Thank you for purchasing a Sealey product. Manufactured to a high standard this product will, if used according to these instructions and properly maintained, give you years of trouble free performance. IMPORTANT: PLEASE READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS CAREFULLY. NOTE THE SAFE OPERATIONAL REQUIREMENTS, WARNINGS AND CAUTIONS. USE THE PRODUCT CORRECTLY AND WITH CARE FOR THE PURPOSE FOR WHICH IT IS INTENDED. FAILURE TO DO SO MAY CAUSE DAMAGE AND/OR PERSONAL INJURY AND WILL INVALIDATE THE WARRANTY. PLEASE KEEP INSTRUCTIONS SAFE FOR FUTURE USE. 1. SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS p WARNING! Ensure all Health and Safety, local authority, and general workshop practice regulations are strictly adhered to when using product. 3 Compression tests on diesel engines should be conducted when the engine is cold. 3 Maintain tools in good and clean condition for best and safest performance. DO NOT use test kit if damaged. 3 Wear approved eye protection. A full range of personal safety equipment is available from your Sealey dealer. 3 Wear suitable clothing to avoid snagging. Do not wear jewellery and tie back long hair. 3 Use proper ventilation and avoid breathing in exhaust fumes. 3 Keep a fire extinguisher to hand. 3 Fuel delivery must be prevented by either operating the engine stop lever or disconnecting fuel pump solenoid. 3 Ensure you keep tester at arms length when relieving pressure to avoid personal injury. 3 Protect your hands from burns as quick release coupling and adaptors may become hot during use. 3 Account for all tools and parts being used and do not leave them in, on or near the engine after use. -

Europe Swings Toward Suvs, Minivans Fragmenting Market Sedans and Station Wagons – Fell Automakers Did Slightly Better Than Cent

AN.040209.18&19.qxd 06.02.2004 13:25 Uhr Page 18 ◆ 18 AUTOMOTIVE NEWS EUROPE FEBRUARY 9, 2004 ◆ MARKET ANALYSIS BY SEGMENT Europe swings toward SUVs, minivans Fragmenting market sedans and station wagons – fell automakers did slightly better than cent. The only new product in an cent because of declining sales for 656,000 units or 5.5 percent. mass-market automakers. Volume otherwise aging arena, the Fiat the Honda HR-V and Mitsubishi favors the non-typical But automakers boosted sales of brands lost close to 2 percent of vol- Panda, was on sale for only four Pajero Pinin. over familiar sedans unconventional vehicles – coupes, ume last year, compared to 0.9 per- months of the year. In terms of brands leading the roadsters, minivans, sport-utility cent for luxury marques. European buyers seem to pro- most segments, Renault is the win- LUCA CIFERRI vehicles exotic cars and multi- Traditional European-brand gressively walk away from large ner with four. Its Twingo leads the spaces such as the Citroen Berlingo automakers dominate the tradi- sedans, down 20.3 percent for the minicar segment, but Renault also AUTOMOTIVE NEWS EUROPE – by 16.8 percent last year to nearly tional car, minivan and premium volume makers and off 11.1 percent leads three other segments that it 3 million units. segments, but Asian brands control in the upper-premium segment. created: compact minivan, Scenic; TURIN – Automakers sold 428,000 These non-traditional vehicle cat- virtually all the top spots in small, large minivan, Espace; and multi- more specialty vehicles last year in egories, some of which barely compact and large SUV segments. -

Driving Resistances of Light-Duty Vehicles in Europe

WHITE PAPER DECEMBER 2016 DRIVING RESISTANCES OF LIGHT- DUTY VEHICLES IN EUROPE: PRESENT SITUATION, TRENDS, AND SCENARIOS FOR 2025 Jörg Kühlwein www.theicct.org [email protected] BEIJING | BERLIN | BRUSSELS | SAN FRANCISCO | WASHINGTON International Council on Clean Transportation Europe Neue Promenade 6, 10178 Berlin +49 (30) 847129-102 [email protected] | www.theicct.org | @TheICCT © 2016 International Council on Clean Transportation TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive summary ...................................................................................................................II Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................... IV 1. Introduction ...........................................................................................................................1 1.1 Physical principles of the driving resistances ....................................................................... 2 1.2 Coastdown runs – differences between EU and U.S. ........................................................ 5 1.3 Sensitivities of driving resistance variations on CO2 emissions ..................................... 6 1.4 Vehicle segments ............................................................................................................................. 8 2. Evaluated data sets ..............................................................................................................9 2.1 ICCT internal database ................................................................................................................. -

SEAT Essence: 70 Years Concentrating Sportiness in a Compact Size

Hola! SEAT essence: 70 years concentrating sportiness in a compact size ▪ In the 70-year history of SEAT, the compact sporty car has always played an important role in its model catalogue ▪ Performance and handling of a sporty car, at the right size and price, with the expected safety: a continuous achievement by SEAT Martorell, 09/11/2020. What does a very light coupé weighting just 720 kilos with rear-wheel drive have to do with a multi-purpose five-seater front-wheel drive that triples its power? Both symbolize how SEAT has always been able to tune in to its audience. SEAT discovered very early on, that sporty cars opened the door to the hearts of the younger public. STAMPA Creating the right sporty car for each era requires being in true harmony with the public. Revolutionize, when necessary. If coupés were all the rage 60 years ago, today even three door cars have almost disappeared. For SEAT's 70 years, we are going to do a quick review of some SEAT models that were icons for the Spanish sporty car market and objects of desire among NEWS NEWS young people of all ages. SEAT 850 Coupé: Latin Heart In 1966 Spain was motorizing at high speed. The SEAT 600 had a big brother, a more spacious and capable touring car, the 850. Only a year later one of the first aspirational cars produced in PRESSE PRESSE Spain was born, the 850 Coupé, an evolution of the SEAT 600. It had the engine hanging at the back, the propulsion was entrusted to the rear wheels and it was only a 2 + 2-seater. -

Manual Seat Ibiza System Porsche

Manual Seat Ibiza System Porsche Nyt myynnissä Seat Ibiza System porsche, 130 000 km, 1989 - Ii. Klikkaa tästä kuvat ja lisätiedot Other. Alloy wheels, Two sets of tyres, Service manual. Find the used SEAT Ibiza Manual that you are looking for with motors.co.uk gauge,SEAT logo boot release,SEAT Portable Navigation system inc SD card slot. Una foto publicada por System Porsche (@seatsystemporsche) el 22 de Jun de Seat por parte de Volkswagen, la cual decidió cancelar el proyecto del IBIZA. Manual Seat Ibiza 1.2/12valve 5door 2003/53 plate 73500 miles cheap ins and tax good on fuel mot feb 2016 recent timing chain and kit very good tyres. Read 1991 Seat Ibiza reviews from real owners. 1991 Seat Ibiza GLX System Porsche 1.2 petrol from Greece Engine and transmission, 1.2 petrol Manual. More power, a new manual gearbox and sharper looks are among the most Audi A3 Cabriolet Convertible (2013 - ) Ford Focus Hatchback (2012 - ) Porsche 911 Coupe First details of the new Seat Ibiza Cupra hot hatch have been revealed infotainment system which can talk to your smartphone via either MirrorLink. Manual Seat Ibiza System Porsche Read/Download Insurance Group 8, 2 Registered Keepers, 16in Alloy Wheels,Air Conditioning,CD Player,Rear Isofix Seat Mounting System,Split Folding Rear Seat,Height. In 1979, SEAT Ritmo production started in Spain and was replaced by a facelifted Gearboxes ranged from a standard 4-speed manual (5-speed optional on CL and "System Porsche"-engined Ibiza, which still had Ritmo underpinnings. Seat Ibiza SC 1.4 Toca 3 door Coupe Manual White. -

Download the Multimac Fitting Guide

Fitting Type SUPERCLUB SUPERCLUB Vehicle 1320 1260 1200 1000 930 A B C 1200 1100 Alfa Romeo 147 Alfa Romeo 156 Alfa Romeo 159 Alfa Romeo 166 Alfa Romeo Brera Alfa Romeo GT Alfa Romeo Guilietta Alfa Romeo Mito Aston Martin DB 5/6 Audi A1 [3 door] Audi A1 [5door] Audi A2 Audi A3 (5 door) Audi A3 (3 door) Audi A3 cabriolet Audi A4 saloon/Avant/Allroad Audi A4 Cabriolet Audi A5 3door Audi A5 5door Audi A5 Cabriolet Audi A6 saloon/Avant/Allroad Audi A7 Audi A8 Audi Q3 Audi Q5 Audi Q7 middle Audi Q7 Rear Audi TT not Cabrio Bently Flying Spur Bently GTC Bently Mulsanne BMW 1 series BMW 1 series cabriolet BMW 2 series BMW 2 series Active T third row BMW 2 series Active Tourer BMW 2 series cabriolet BMW 3 series BMW 3 series Cabriolet BMW 4 series BMW 4 series Cabriolet BMW 5 series BMW 5series GT BMW 6 series 2 door BMW 6 series cabrio BMW 7 series BMW i3 BMW X1 BMW X3 BMW X5 5seat BMW X5 7seat middle BMW X5 7seat rear BMW X6 bench seat Chevrolet Aveo Chevrolet Captiva middle row Chevrolet Captiva third row Chevrolet Cruze Chevrolet Kalos Chevrolet Lacetti Chevrolet Matiz Chevrolet Orlando middle row Chevrolet Orlando third row Chevrolet Spark Chevrolet Tacuma Chrysler 300C Chrysler Grand Voyager middle Chrysler Grand Voyager rear Chrysler neon Chrysler PT cruiser Chrysler voyager middle row Chrysler Voyager rear row Citroen -

Harewood Hillclimb

Harewood Hillclimb Summer Holiday Hillclimb Entry List at 22/08/20 Class Shared No. Driver Name Car CC S/T Club Hometown 1A S 716 Ryan Billington Peugeot 205 XS 1360 BARC(Y) Halifax 1A 14 Brian Hobbs Mini Cooper 1380 BARC(Y) Whitby 1A 15 Michael Holmes Toyota Starlet Sportif 1332 BARC(Y) Otley 1A S 16 Sam Billington Peugeot 205 XS 1360 BARC(Y) Halifax 1A 17 John Pinder Skoda Fabia 1398 ANCC Bradford 1A 18 David Taylor Morris Cooper S 1380 BARC(Y) Doncaster 1A 19 Mark Teale Suzuki Swift GTi 1370 BARC(Y) Bradley 1B S 724 Alexander Hall Eunos Roadster 1597 BARC(Y) Harrogate 1B S 726 David Lanfranchi Mazda MX5 1800 BARC(Y) Menston 1B S 727 Stephen Kettlewell Peugeot 206 GTi 1997 BARC(Y) Garforth 1B S 729 Mick Tetlow Renault Clio 182 1998 BARC(Y) South Elmsall 1B 21 Nick Jaggard Citroen Saxo VTS 1600 BARC(Y) Northallerton 1B 22 Nabil Zahlan Seat Ibiza FR 1400 T BARC(Y) Whitby 1B 23 Charlie Deere Toyota Celica 190 1800 BARC(Y) Barnard Castle 1B S 24 Alexander Rhodes Eunos Roadster 1597 BARC(Y) Doncaster 1B 25 James Castledine Ford Fiesta 1998 BARC(Y) Consett 1B S 26 Andy Harrison Mazda MX5 1800 BARC(Y) Shipley 1B S 27 James Izzard Peugeot 206 GTI 180 1997 BARC(Y) Guiseley 1B 28 Daniel Ashall Renault Clio 1998 BARC(Y) Chesterfield 1B S 29 Luke Downie Renault Clio 182 1998 BARC(Y) Adwick 1B 30 Nigel Trundle Abarth 500 1368 T ANCC Preston 1B 31 Shane Jowett Honda Civic Type R 1998 BARC(Y) Riddings 1B 32 Tony Pickering Renault Clio 182 1998 BARC(Y) Pateley Bridge 1B 33 David Sykes Peugeot 205 GTi 1905 BARC(Y) Huddersfield 1B 34 David Marshall Peugeot