Buried Child Study Guide – Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI As of 3/1/2017

University of Northern Colorado School of Theatre Arts and Dance DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI as of 3/1/2017 Broadway – 25 Performers (55 Productions) Josh Buscher – West Side Story 2009 (OC), Pricilla Queen of the Desert (OC), Big Fish (OC) Ryan Dinning – Machinal (OC) Jenny Fellner – Wicked, Mamma Mia, The Boyfriend, Pal Joey (OC) Scott Foster – Forbidden Broadway (Alive and Kicking) 2013, Brooklyn (OC), Forbidden Broadway (Alive and Kicking) 2014 Greg German – Assassins (OC), Biloxi Blues (OC), Boeing/Boeing Patty Goble – Bye Bye Birdie 2009 (OC), Curtains (OC), The Woman in White (OC), La Cage Aux Follies 2004 (OC), Kiss Me Kate 1999 (OC), Ragtime (OC), Phantom of the Opera Derek Hanson – Anything Goes (Sutton Foster), Side Show (2014 Revival), An American in Paris (2016), Tamara Hayden – Les Miz, Cabaret Autumn Hulbert – Legally Blonde Aisha Jackson – Beautiful: The Carol King Musical, Waitress (OC) Ryan Jesse – Jersey Boys Patricia Jones – Buried Child (OC), Indiscretions (w/Kathleen Turner) Andy Kelso – Mamma Mia, Kinky Boots (OC) Beth Malone – Ring of Fire (OC), Fun Home (OC)+ Victoria Matlock – Million Dollar Quartet (OC) Jason Olazabal – Julius Caesar (OC) (w/Denzel Washington) Laura Ryan – Country Roads The John Denver Musical (OC) Lisa Simms – A Chorus Line Andrea Dora Smith – Tarzan, Motown (OC) Erica Sweany – Honeymoon in Vegas – The Musical (OC) Jason Veasey – The Lion King Jason Watson – Mamma Mia Aléna Watters – Sister Act (OC), Adams Family Musical (OC), West Side Story 2009, Wysandria Woolsey – Chess, Parade, Beauty and the -

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

CLONES, BONES and TWILIGHT ZONES: PROTECTING the DIGITAL PERSONA of the QUICK, the DEAD and the IMAGINARY by Josephj

CLONES, BONES AND TWILIGHT ZONES: PROTECTING THE DIGITAL PERSONA OF THE QUICK, THE DEAD AND THE IMAGINARY By JosephJ. Beard' ABSTRACT This article explores a developing technology-the creation of digi- tal replicas of individuals, both living and dead, as well as the creation of totally imaginary humans. The article examines the various laws, includ- ing copyright, sui generis, right of publicity and trademark, that may be employed to prevent the creation, duplication and exploitation of digital replicas of individuals as well as to prevent unauthorized alteration of ex- isting images of a person. With respect to totally imaginary digital hu- mans, the article addresses the issue of whether such virtual humans should be treated like real humans or simply as highly sophisticated forms of animated cartoon characters. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN TR O DU C T IO N ................................................................................................ 1166 II. CLONES: DIGITAL REPLICAS OF LIVING INDIVIDUALS ........................ 1171 A. Preventing the Unauthorized Creation or Duplication of a Digital Clone ...1171 1. PhysicalAppearance ............................................................................ 1172 a) The D irect A pproach ...................................................................... 1172 i) The T echnology ....................................................................... 1172 ii) Copyright ................................................................................. 1176 iii) Sui generis Protection -

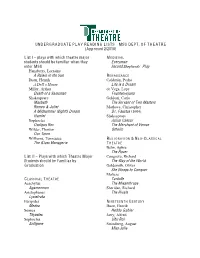

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

April 2021 New Titles List University of Dubuque

April 2021 New Titles List University of Dubuque Local Item Call Local Item Permanent Number Author Name Title Publisher NamePublication Date Edition Language Name Material Format Material Subformat Shelving Location N/A Neonatology today. Neonatology Today,2006 N/A English JOURNALS/MAGAZIN EJOURNALS/EMAGA ES ZINES Parkman, Francis, A half century of Little, Brown, and Co.,1899 Frontenac English BOOKS PRINTBOOK conflict / edition. Schur, Michael,Scanlon, The Good Place. Universal 2019 N/A English VIDEOS DVDS Claire,Miller, Beth Television,Shout! Factory, McCarthy,Holland, Dean,Bell, Kristen,Danson, Ted,Harper, William Jackson,Jamil, Jameela,Carden, D'Arcy,Jacinto, Manny,; Shout! Factory (Firm),Universal Television (Firm), AM151 .T54 2019 Garcia, Tristan,Normand, Theater, garden, ÉCAL/University of Art 2019 N/A English BOOKSPRINTBOOK New Book Collection: Vincent,; École cantonale bestiary :a and Design Lausanne 1st Floor d'art de Lausanne,Haute materialist history of ;Sternberg Press, école spécialisée de exhibitions / Suisse occidentale. BF789.C7 P3713 Pastoureau, Michel,; Green :the history of Princeton University 2014 N/A English BOOKSPRINTBOOK New Book Collection: 2014 Gladding, Jody, a color / Press, 1st Floor BJ1521 .H76 2020 Miller, Christian B.,West, Integrity, honesty, Oxford University Press,2020 N/A English BOOKSPRINTBOOK New Book Collection: Ryan, and truth seeking / 1st Floor BR65.A9 W47 Wessel, Susan, On compassion, Bloomsbury Academic,2020 N/A English BOOKSPRINTBOOK New Book Collection: 2020 healing, suffering, 1st Floor and the purpose of the emotional life / BS195 .R48 2019 Wansbrough, Henry, The Revised New Image,2019 First U.S. edition. English BOOKSPRINTBOOK New Book Collection: Jerusalem Bible 1st Floor :study edition / BS2553 .R83 Ruden, Sarah, The Gospels / Modern Library,2021 First edition. -

Jessica Lange Regis Dialogue Formatted

Jessica Lange Regis Dialogue with Molly Haskell, 1997 Bruce Jenkins: Let me say that these dialogues have for the better part of this decade focused on that part of cinema devoted to narrative or dramatic filmmaking, and we've had evenings with actors, directors, cinematographers, and I would say really especially with those performers that we identify with the cutting edge of narrative filmmaking. In describing tonight's guest, Molly Haskell spoke of a creative artist who not only did a sizeable number of important projects but more importantly, did the projects that she herself wanted to see made. The same I think can be said about Molly Haskell. She began in the 1960s working in New York for the French Film Office at that point where the French New Wave needed a promoter and a writer and a translator. She eventually wrote the landmark book From Reverence to Rape on women in cinema from 1973 and republished in 1987, and did sizable stints as the film reviewer for Vogue magazine, The Village Voice, New York magazine, New York Observer, and more recently, for On the Issues. Her most recent book, Holding My Own in No Man's Land, contains her last two decades' worth of writing. I'm please to say it's in the Walker bookstore, as well. Our other guest tonight needs no introduction here in the Twin Cities nor in Cloquet, Minnesota, nor would I say anyplace in the world that motion pictures are watched and cherished. She's an internationally recognized star, but she's really a unique star. -

Sam Shepard One Acts: War in Heaven (Angel’S Monologue), the Curse of the Raven’S Black Feather, Hail from Nowhere, Just Space Rhythm

Sam Shepard One Acts: War in Heaven (Angel’s Monologue), The Curse of the Raven’s Black Feather, Hail from Nowhere, Just Space Rhythm Resource Guide for Teachers Created by: Lauren Bloom Hanover, Director of Education 1 Table of Contents About Profile Theatre 3 How to Use This Resource Guide 4 The Artists 5 Lesson 1: Who is Sam Shepard? Classroom Activities: 1) Biography and Context 6 2) Shepard in His Own Words 6 3) Shepard Adjectives 7 Lesson 2: Influences on Shepard Classroom Activities 1) Exploring Similar Themes in O’Neill and Shepard 16 2) Exploring Similar Styles in Beckett and Shepard 17 3) Exploring the Influence of Music on Shepard 18 Lesson 3: Inspired by Shepard Classroom Activities 1) Reading Samples of Shepard 28 2) Creative Writing Inspired by Shepard 29 3) Directing One’s Own Work 29 Lesson 4: What Are You Seeing Classroom Activities 1) Pieces Being Performed 33 2) Statues 34 3) Staging a Monologue 36 Lesson 5: Reflection Classroom Activities 1) Written Reflection 44 2) Putting It All Together 45 2 About Profile Theatre Profile Theatre was founded in 1997 with the mission of celebrating the playwright’s contribution to live theater. To that end, Profile programs a full season of the work of a single playwright. This provides our community with the opportunity to deeply engage with the work of our featured playwright through performances, readings, lectures and talkbacks, a unique experience in Portland. Our Mission realized... Profile invites our audiences to enter a writer’s world for a full season of plays and events. -

William and Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM AND MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Exploring Films About Ethical Leadership: Can Lessons Be Learned?

EXPLORING FILMS ABOUT ETHICAL LEADERSHIP: CAN LESSONS BE LEARNED? By Richard J. Stillman II University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center Public Administration and Management Volume Eleven, Number 3, pp. 103-305 2006 104 DEDICATED TO THOSE ETHICAL LEADERS WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE 9/11 TERROIST ATTACKS — MAY THEIR HEORISM BE REMEMBERED 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 106 Advancing Our Understanding of Ethical Leadership through Films 108 Notes on Selecting Films about Ethical Leadership 142 Index by Subject 301 106 PREFACE In his preface to James M cG regor B urns‘ Pulitzer–prizewinning book, Leadership (1978), the author w rote that ―… an im m ense reservoir of data and analysis and theories have developed,‖ but ―w e have no school of leadership.‖ R ather, ―… scholars have worked in separate disciplines and sub-disciplines in pursuit of different and often related questions and problem s.‖ (p.3) B urns argued that the tim e w as ripe to draw together this vast accumulation of research and analysis from humanities and social sciences in order to arrive at a conceptual synthesis, even an intellectual breakthrough for understanding of this critically important subject. Of course, that was the aim of his magisterial scholarly work, and while unquestionably impressive, his tome turned out to be by no means the last word on the topic. Indeed over the intervening quarter century, quite to the contrary, we witnessed a continuously increasing outpouring of specialized political science, historical, philosophical, psychological, and other disciplinary studies with clearly ―no school of leadership‖with a single unifying theory emerging. -

David Rabe's Good for Otto Gets Star Studded Cast with F. Murray Abraham, Ed Harris, Mark Linn-Baker, Amy Madigan, Rhea Perl

David Rabe’s Good for Otto Gets Star Studded Cast With F. Murray Abraham, Ed Harris, Mark Linn-Baker, Amy Madigan, Rhea Perlman and More t2conline.com/david-rabes-good-for-otto-gets-star-studded-cast-with-f-murray-abraham-ed-harris-mark-linn-baker-amy- madigan-rhea-perlman-and-more/ Suzanna January 30, 2018 Bowling F. Murray Abraham (Barnard), Kate Buddeke (Jane), Laura Esterman (Mrs. Garland), Nancy Giles (Marci), Lily Gladstone (Denise), Ed Harris (Dr. Michaels), Charlotte Hope (Mom), Mark Linn- Baker (Timothy), Amy Madigan (Evangeline), Rileigh McDonald (Frannie), Kenny Mellman (Jerome), Maulik Pancholy (Alex), Rhea Perlman (Nora) and Michael Rabe (Jimmy), will lite up the star in the New York premiere of David Rabe’s Good for Otto. Rhea Perlman took over the role of Nora, after Rosie O’Donnell, became ill. Directed by Scott Elliott, this production will play a limited Off-Broadway engagement February 20 – April 1, with Opening Night on Thursday, March 8 at The Pershing Square Signature Center (The Alice Griffin Jewel Box Theatre, 480 West 42nd Street). Through the microcosm of a rural Connecticut mental health center, Tony Award-winning playwright David Rabe conjures a whole American community on the edge. Like their patients and their families, Dr. Michaels (Ed Harris), his colleague Evangeline (Amy Madigan) and the clinic itself teeter between breakdown and survival, wielding dedication and humanity against the cunning, inventive adversary of mental illness, to hold onto the need to fight – and to live. Inspired by a real clinic, Rabe finds humor and compassion in a raft of richly drawn characters adrift in a society and a system stretched beyond capacity. -

Sam Shepard's Dramaturgical Strategies Susan

Fall 1988 71 Estrangement and Engagement: Sam Shepard's Dramaturgical Strategies Susan Harris Smith Current scholarship reveals an understandable preoccupation with and confusion over Sam Shepard's most prominent characteristics, his language and imagery, both of which are seminal features of his technical innovation. In their attempts to describe or define Shepard's idiosyncratic dramaturgy, critics variously have called it absurdist, surrealistic, mythic, Brechtian, and even Artaudian. Most critics, too, are concerned primarily with his themes: physical violence, erotic dynamism, and psychological dissolution set against the cultural wasteland of modern America (Marranca, ed.). But in focusing on Shepard's imagery, language, and themes, some critics ignore theatrical performance. Beyond observing that many of Shepard's role-playing characters engage in power struggles with each other, few critics have concerned themselves with Shepard's structural strategies or with the ways in which he manipulates his audience. One who has addressed the issue, Bonnie Marranca, writes: Characters often engage in, "performance": they create roles for themselves and dialogue, structuring new realities. ... It might be called an aesthetics of actualism. In other words, the characters act themselves out, even make them• selves up, through the transforming power of their imagina• tion. An Assistant Professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh and the author of Masks in Modern Drama, Susan Harris Smith is currently working on a book on American drama. A shorter version of this article was presented at the South• eastern Modern Languages Association in 1985. 72 Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism Because the characters are so free of fixed reality, their imagination plays a key role in the narratives.