Biodiversity in Central African Forests: an Overview of Knowledge, Main Challenges and Conservation Measures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Itombwe Massif, Democratic Republic of Congo: Biological Surveys and Conservation, with an Emphasis on Grauer's Gorilla and Birds Endemic to the Albertine Rift

Oryx Voi 33 No 4 October -.939 The Itombwe Massif, Democratic Republic of Congo: biological surveys and conservation, with an emphasis on Grauer's gorilla and birds endemic to the Albertine Rift llambu Omari, John A. Hart, Thomas M. Butynski, N. R. Birhashirwa, Agenonga Upoki, Yuma M'Keyo, Faustin Bengana, Mugunda Bashonga and Norbert Bagurubumwe Abstract In 1996, the first major biological surveys in species were recorded during the surveys, including the the Itombwe Massif in over 30 years revealed that sig- Congo bay owl Phodilus prigoginei, which was previously nificant areas of natural habitat and remnant faunal known from a single specimen collected in Itombwe populations remain, but that these are subject to ongo- nearly 50 years ago. No part of Itombwe is officially ing degradation and over-exploitation. At least 10 areas protected and conservation initiatives are needed ur- of gorilla Gorilla gorilla graueri occurrence, including gently. Given the remoteness and continuing political eight of 17 areas identified during the first survey of the instability of the region, conservation initiatives must species in the massif in 1959, were found. Seventy-nine collaborate with traditional authorities based in the gorilla nest sites were recorded and at least 860 gorillas massif, and should focus at the outset on protecting the were estimated to occupy the massif. Fifty-six species of gorillas and limiting further degradation of key areas. mammals were recorded. Itombwe supports the highest representation, of any area, of bird species endemic to Keywords Afromontane forests, Albertine Rift, Demo- the Albertine Rift highlands. Twenty-two of these cratic Republic of Congo, endemic avifauna, gorillas. -

Albertine Rift Nov04

africa & madagascar "meeting the challenge" Albertine Rift Montane Forests Ecoregion Programme 1. Background Duration: The Albertine Rift Montane Forests Ecoregion is an area of Current phase is 5 exceptional faunal and floral endemism. These afromontane years, from 2001 to forests also support many endangered species such as the 2005. Mountain and Eastern Lowland gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei and G. b. graueri ), which are among the most charismatic Funding Status: flagship species in Africa, and an effective target for much of the Partly funded by WWF- current conservation investment in the area. DK and SE (25%); the remaining is yet to be The mountain chain comprising the Albertine Rift straddles the funded (currently borders of five different nations: Democratic Republic of Congo covered through Direct (over 70% of the Ecoregion), Uganda (20%), Rwanda (6%), Burundi Cost Recovery). (3%) and Tanzania (1%). Executing Agency: The Albertine Rift has been identified by all key international WWF Eastern Africa conservation NGOs as a top priority area for biodiversity Regional Programme conservation in Africa and the Ecoregion is a priority Ecoregion for Office (WWF EARPO). WWF-International. 2. Goal and Objectives The Goal of the Albertine Rift Ecoregion Programme is to ensure the long-term conservation of the Albertine Rift Montane Forests and other important interconnected ecosystems. The objectives are: ? To develop a strategic framework for conservation efforts in the ecoregion with a wide variety of stakeholders ? To implement and co-ordinate a set of comprehensive and inter-related field projects in the Albertine Rift ? To support national authorities in the planning and management of protected areas and buffer zones 3. -

Virunga Landscape

23. Virunga Landscape Th e Landscape in brief Coordinates: 1°1’29’’N – 1°44’21’’S – 28°56’11’’E – 30°5’2’’E. Area: 15,155 km2 Elevation: 680–5,119 m Terrestrial ecoregions: Ecoregion of the Afroalpine barrens of Ruwenzori-Virunga Ecoregion of the Afromontane forests of the Albertine Rift Ecoregion of the forest-savannah mosaic of Lake Victoria Aquatic ecoregions: Mountains of the Albertine Rift Lakes Kivu, Edward, George and Victoria Protected areas: Virunga National Park, DRC, 772,700 ha, 1925 Volcans National Park, Rwanda, 16,000 ha, 1925 Rutshuru Hunting Domain, 64,200 ha, 1946 added Bwindi-Impenetrable National Park situ- ated a short distance away from the volcanoes in southwest Uganda. Th is complex functions as a single ecosystem and many animals move across the borders, which permits restoration of the populations1. Physical environment Relief and altitude Th e Landscape is focused on the central trough of the Albertine Rift, occupied by Lake Figure 23.1. Map of Virunga Landscape (Sources: CARPE, Edward (916 m, 2,240 km²), and vast plains DFGFI, JRC, SRTM, WWF-EARPO). at an altitude of between 680 and 1,450 m. Its western edge stretches along the eastern bluff of Location and area the Mitumba Mountain Range forming the west- ern ridge of the rift. In the northeast, it includes he Virunga Landscape covers 15,155 km² the western bluff of the Ruwenzori horst (fault Tand includes two contiguous national parks, block) with its active glaciers, whose peak reaches Virunga National Park in DRC and Volcans a height of 5,119 m and whose very steep relief National Park in Rwanda, the Rutshuru Hunting comprises numerous old glacial valleys (Figure Zone and a 10 km-wide strip at the edge of the 23.2). -

Dja Faunal Reserve Cameroon

DJA FAUNAL RESERVE CAMEROON This is one of the largest and best-protected rainforests in Africa, almost completely surrounded by the Dja river which forms its boundary. 90% of its area is still undisturbed. It is one of IUCN’s fifteen critical zones for the conservation of central African biodiversity and as a result of its inaccessibility, its transitional climate, floristic diversity and borderline location retains a rich vertebrate fauna with 109 species of mammals and a wide variety of primates. Threats to the site: Inadequate management has resulted in erosion of biodiversity, a growth of forest exploitation, agricultural clearance and potential pollution from a cobalt mine. COUNTRY Cameroon NAME Dja Faunal Reserve (La Réserve de Faune du Dja) NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SITE 1987: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under Natural Criteria ix and x. INTERNATIONAL DESIGNATION 1981: Designated a Biosphere Reserve under the UNESCO Man & Biosphere Programme (526,000 ha). IUCN MANAGEMENT CATEGOCATEGORYRYRYRY VI: Managed Resource Protected Area BIOGEOGRAPHICAL PROVINCE Congo Rain Forest (3.2.1) GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION On and nearly surrounded by the Dja River in the Centre-Sud and Est Provinces of Cameroon, 243 km south-east of the capital, Yaoundé, and 5 km west of Lomié. The river forms a natural boundary except to the northeast. Coordinates: 2 °49'-3°23'N, 12 °25'-13 °35'E. DATES AND HISTORY OF ESTABLISHMENT 1932: The area received some protection. In 1947 certain species within Dja were protected by Decree 2254 which regulated hunting in the French African territories; 1950: Protected as a Réserve de Faune et de Chasse by Arrêté 75/50; 1973: Protected as a Réserve de Faune (623,619 ha) under National Forestry Act Ordinance 73/18. -

Namibia & the Okavango

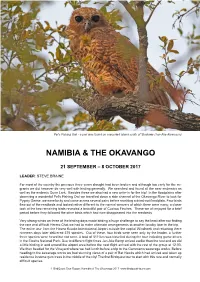

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

International Gorilla Conservation Programme Greater Virunga Transboundary Collaboration

International Gorilla Conservation Programme Greater Virunga Transboundary Collaboration Anna Behm Masozera Email: [email protected] Phone: +250 782332280 (voice messages can be left at +1 802 999 4958) www.greatervirunga.org www.igcp.org Central Albertine Rift: Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, and Uganda. Size: Mountain gorilla habitat = 796.4 km2 Protected Areas in the Greater Virunga Landscape = 11,826.7 km2 Page 1 of 6 Participants in coordinating the ongoing transboundary cooperation: National Government: • Ministry of Environment Nature Conservation, and Tourism (DRC) • Ministry of Trade and Industry (Rwanda) • Ministry of Tourism, Wildlife and Antiquities (Uganda) Local Government: • North Kivu Province and Orientale Province (DRC) • many Districts (Uganda and Rwanda) Protected area administration: • Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature (DRC) • Rwanda Development Board (Rwanda) • Uganda Wildlife Authority (Uganda) International NGOs: • Wildlife Conservation Society • WWF • International Gorilla Conservation Programme (coalition of Fauna & Flora International and WWF) • Mountain Gorilla Veterinary Project/Gorilla Doctors, • Diane Fossey Gorilla Fund International Objectives: 1) To promote and coordinate conservation of biodiversity and related socio-cultural values within the Greater Virunga protected area network; 2) To develop strategies for collaborative management of biodiversity; 3) To promote and ensure coordinated planning, monitoring, and evaluation of implementation of transboundary conservation and development -

Historical Background: Early Exploration in the East African Rift--The Gregory Rift Valley

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 26, 2021 SIR PETER KENT Historical background: Early exploration in the East African Rift--The Gregory Rift Valley In relation to modern lines of communication it seems surprising that the Gregory Rift Valley was the last part of the system to become known. Much of the earlier exploration had however been centred on the problem of the sources of the Nile, and in consequence the Western or Albertine Rift was explored by Samuel Baker as early as 1862/63 (Baker 1866). Additionally there was a strong tendency to use the convenient base at Zanzibar Island for journeys inland by the Arab slave trading routes from Pangani and Bagamoyo; these led to the Tanganyika Rift and Nyasaland rather than to the area of modern Kenya. The first penetrations into the Gregory Rift area were in I883; Joseph Thomson made an extensive journey into Central Kenya which he described in his book of 1887, 'Through Masai Land' which had as a subtitle, 'a journey of exploration among the snowclad volcanic mountains and strange tribes of Eastern Equatorial Africa--being the narrative of the Royal Geographical Society's Expedition to Mount Kenya and Lake Victoria Nyanza i883-84'. In his classic journey Thomson practically encircled the lower slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro and reached the Gregory Rift wall near the Ngong Hills. He then went north to Lake Baringo and westwards to Lake Victoria, before returning to his starting point at Mombasa. His observations on the geology were of good standard for the time. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Comparative Phylogeography of Three Endemic Rodents from the Albertine Rift, East Central Africa

Molecular Ecology (2007) 16, 663–674 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03153.x ComparativeBlackwell Publishing Ltd phylogeography of three endemic rodents from the Albertine Rift, east central Africa MICHAEL H. HUHNDORF,*† JULIAN C. KERBIS PETERHANS†‡ and SABINE S. LOEW*† *Department of Biological Sciences, Behaviour, Ecology, Evolution and Systematics Section, Illinois State University, Normal, Illinois 61790-4120, USA, †Department of Zoology, The Field Museum, Chicago, Illinois, 60605-2496, USA, ‡University College, Roosevelt University, Chicago, Illinois, 60605, USA Abstract The major aim of this study was to compare the phylogeographic patterns of codistributed rodents from the fragmented montane rainforests of the Albertine Rift region of east central Africa. We sampled individuals of three endemic rodent species, Hylomyscus denniae, Hybomys lunaris and Lophuromys woosnami from four localities in the Albertine Rift. We analysed mitochondrial DNA sequence variation from fragments of the cytochrome b and con- trol region genes and found significant phylogeographic structuring for the three taxa examined. The recovered phylogenies suggest that climatic fluctuations and volcanic activity of the Virunga Volcanoes chain have caused the fragmentation of rainforest habitat during the past 2 million years. This fragmentation has played a major role in the diversification of the montane endemic rodents of the region. Estimation of the divergence times within each species suggests a separation of the major clades occurring during the mid to late Pleistocene. Keywords: Africa, Albertine Rift, control region, cytochrome b, phylogeography, rodent Received 26 May 2006; revision accepted 1 September 2006 The Albertine Rift is the western branch of the Great Rift Introduction Valley in central and east Africa. -

Why Eat Wild Meat?

May 2021 Why Eat Wild Meat? Local food choices, food security and desired design features of wild meat alternative projects in Cameroon Author information Stephanie Brittain is a postdoctoral researcher in the Interdisciplinary Centre for Conservation Science (ICCS) at the University of Oxford. [email protected] About the project For more information about the Why Eat Wild Meat? project, visit www.iied.org/why-eat-wild-meat Acknowledgements With thanks to colleagues from the Why Eat Wild Meat? project for their inputs, including Mama Mouamfon (FCTV), Cédric Thibaut Kamogne Tagne (FCTV), E J Milner-Gulland (ICCS), Francesca Booker (IIED), Dilys Roe (IIED), and Neil Maddison (The Conservation Foundation). IIED is a policy and action research organisation. We promote sustainable development to improve livelihoods and protect the environments on which these livelihoods are built. We specialise in linking local priorities to global challenges. IIED is based in London and works in Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and the Pacific, with some of the world’s most vulnerable people. We work with them to strengthen their voice in the decision- making arenas that affect them — from village councils to international conventions. Published by IIED, May 2021 http://pubs.iied.org/20176IIED Citation: Brittain S (2021) Why Eat Wild Meat? Local food choices, food security and desired design features of wild meat alternative projects in Cameroon. Project Report. IIED, London All graphics were created for this report. International Institute for Environment and Development 235 High Holborn, London WC1V 7LE Tel: +44 (0)20 3463 7399 Fax: +44 (0)20 3514 9055 www.iied.org @iied www.facebook.com/theIIED Download more publications at http://pubs.iied.org IIED publications may be shared and republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). -

Iucn Summary 4071 Dja Faunal Reserve

WORLD KERlTAGE NOMINATION -- IUCN SUMMARY 4071 DJA FAUNAL RESERVE (CAMERON) Summary prepared by IUCN (April 1987) based on the original nomination submitted by Cameroon. This original and all documents presented in support of this nomination will be available for consultation at the meetings of the Bureau and the Committee. 1. LOCATION, On the Dja River in the Central-Southern and Eastern Provinces of Cameroon, 243km south-east of Yaoundg, and 5km west of Lomie. 2'49'-3'23'N, 12'25'-13'35'E. 2. JURIDICAL DATA: Protected as a 'rgserve de faune et de chasse' in 1950, and then as a IrEserve de faune' under the National Forestry Act Ordinance 1973. Accepted as a Biosphere Reserve in 1981. Proposed as a National Park. Asea is 526,000 ha. 3. IDENTIFICATIONI The Dja reserve is virtually encircled by the Dja River which flows west along the long northern boundary of the reserve, and then along the southern boundary, before flowing southeast as a tributary to the Congo. Cliffs run along the course of the river in the south for some 6Okm, and are associated with a section of the river broken up by rapids and waterfalls. Except in the south-east of the reserve, the relief is fairly flat and consists of a succession of round-topped hills. The vegetation mainly comprises dense evergreen Congo rainforest with a main canopy at 30-40m rising to 60m. Some 43 species of tree form the canopy, with legumes being particulary common. The area is known to have a wide range of primate species including lowland gorilla, greater white-nosed guenon, moustached guenon, crowned guenon, talapoin, white-collared mangabey, white-cheeked mangabey, agile mangabey, drill, mandrill, potto, Demdorff's galago, black and white colobus monkey and chimpanzee. -

Rift-Valley-1.Pdf

R E S O U R C E L I B R A R Y E N C Y C L O P E D I C E N T RY Rift Valley A rift valley is a lowland region that forms where Earth’s tectonic plates move apart, or rift. G R A D E S 6 - 12+ S U B J E C T S Earth Science, Geology, Geography, Physical Geography C O N T E N T S 9 Images For the complete encyclopedic entry with media resources, visit: http://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/rift-valley/ A rift valley is a lowland region that forms where Earth’s tectonic plates move apart, or rift. Rift valleys are found both on land and at the bottom of the ocean, where they are created by the process of seafloor spreading. Rift valleys differ from river valleys and glacial valleys in that they are created by tectonic activity and not the process of erosion. Tectonic plates are huge, rocky slabs of Earth's lithosphere—its crust and upper mantle. Tectonic plates are constantly in motion—shifting against each other in fault zones, falling beneath one another in a process called subduction, crashing against one another at convergent plate boundaries, and tearing apart from each other at divergent plate boundaries. Many rift valleys are part of “triple junctions,” a type of divergent boundary where three tectonic plates meet at about 120° angles. Two arms of the triple junction can split to form an entire ocean. The third, “failed rift” or aulacogen, may become a rift valley.