TOC 0334 CD Booklet.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Print 110774Bk Levitzki

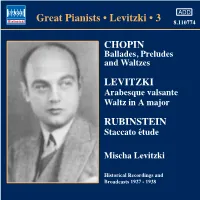

110774bk Levitzki 8/7/04 8:02 pm Page 5 Mischa Levitzki: Piano Recordings Vol. 3 Also available on Naxos ADD Gramophone Company Ltd., 1927-1933 RACHMANINOV: CHOPIN: @ Prelude in G minor, Op. 23, No. 5 3:22 Great Pianists • Levitzki • 3 8.110774 1 Prelude in C major, Op. 28 0:55 Recorded 21st November 1929 2 Prelude in A major, Op. 28, No. 7 0:55 Matrix Cc 18200-1a; Cat. D 1809 3 Prelude in F major, Op. 28, No. 23 1:24 Recorded 21st November 1929 RCA Victor, 1938 Matrix Bb 18113-3a; Cat.DA1223 LEVITZKI: 4 Waltz No. 8 in A flat major, Op. 64, No. 3 3:00 # Waltz in A major, Op. 2 1:46 CHOPIN Recorded 19th November 1928 Recorded 5th May 1938; Matrix Cc 14770-1; Cat.ED18 Matrices BS 023101-1, BS 023101-1A (NP), Ballades, Preludes BS 023101-2, BS 023101-2A (NP); Cat. 2008-A 5 Waltz No. 11 in G flat major, $ Arabesque valsante, Op. 6 3:23 and Waltzes Op. 70, No. 1 2:26 Recorded 5th May 1938; Recorded 19th November 1928 Matrices BS 023100-1, BS 023100-1A (NP), Matrix Cc 14769-3; Cat.ED18 BS 023100-2, BS 023100-2A (NP), BS 023100-3, 6 Ballade No. 3 in A flat major, Op. 47 6:26 BS023100-3A (NP); Cat. 2008-B Recorded 22nd November 1928 Broadcasts LEVITZKI Matrices Bb 11786-5 and 11787-5; Cat.EW64 26th January, 1935: 7 Nocturne No. 5 in F sharp major, CHOPIN: Arabesque valsante Op. 15, No. -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

The-Piano-Teaching-Legacy-Of-Solomon-Mikowsky.Pdf

! " #$ % $%& $ '()*) & + & ! ! ' ,'* - .& " ' + ! / 0 # 1 2 3 0 ! 1 2 45 3 678 9 , :$, /; !! < <4 $ ! !! 6=>= < # * - / $ ? ?; ! " # $ !% ! & $ ' ' ($ ' # % %) %* % ' $ ' + " % & ' !# $, ( $ - . ! "- ( % . % % % % $ $ $ - - - - // $$$ 0 1"1"#23." 4& )*5/ +) * !6 !& 7!8%779:9& % ) - 2 ; ! * & < "-$=/-%# & # % %:>9? /- @:>9A4& )*5/ +) "3 " & :>9A 1 The Piano Teaching Legacy of Solomon Mikowsky by Kookhee Hong New York City, NY 2013 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by Koohe Hong .......................................................3 Endorsements .......................................................................3 Comments ............................................................................5 Part I: Biography ................................................................12 Part II: Pedagogy................................................................71 Part III: Appendices .........................................................148 1. Student Tributes ....................................................149 2. Student Statements ................................................176 -

Chopin: Poet of the Piano

GOING BEHIND THE NOTES: EXPLORING THE GREAT PIANO COMPOSERS AN 8-PART LECTURE CONCERT SERIES CHOPIN: POET OF THE PIANO Dr. George Fee www.dersnah-fee.com Performance: Nocturne in E Minor, Op. 72, No. 1 (Op. Posth.) Introduction Early Life Performance: Polonaise in G minor (1817) Paris and the Polish Community in Paris Performance: Mazurkas in G-sharp Minor and B Minor, Op. 33, Nos. 1 and 4 Scherzo in C-sharp Minor, Op. 39 The Man Chopin (1810-1849) Parisian Society and Chopin as Teacher Chopin’s Performing and More on his Personality Performance: Waltz in A-flat Major, Op. 42 10 MINUTE BREAK Chopin’s Playing Performance: Nocturne in D-flat Major, Op. 27, No. 2 Chopin’s Music Performance: Mazurka in C-sharp Minor, Op. 50, No. 3 Chopin’s Teaching and Playing Chopin Today Chopin’s Relationship with Aurore Dupin (George Sand) Final Years Performance: Mazurka in F Minor, Op .68 No.4 Polonaise in A-flat Major Op. 53 READING ON CHOPIN Atwood, William G. The Parisian Worlds of Frédéric Chopin. Yale University Press, 1999. Eigeldinger, Jean-Jacques. Chopin: pianist and teacher as seen by his pupils. Cambridge University Press, 1986. Marek, George R. Chopin. Harper and Row, 1978. Methuen-Campbell, James. Chopin Playing: From the Composer to the Present Day. Taplinger Publishing Co., 1981. Siepmann, Jeremy. Chopin: The Reluctant Romanic. Victor Gollancz, 1995. Szulc, Tad. Chopin in Paris: The Life and Times of the Romantic Composer. Da Capo Press, 1998. Walker, Alan. Fryderyk Chopin: A Life and Times. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018. -

Review of “22 Chopin Studies” by Leopold Godowsky by OPUS KLASSIEK , Published on 25 February 2013

Review of “22 Chopin Studies” by Leopold Godowsky by OPUS KLASSIEK , published on 25 February 2013 Leopold Godowsky (Zasliai, Litouwen 1870 - New York 1938) was sailing with the tide around 1900: the artistic and culturally rich turn of the century was a golden age for pianists. They were given plenty of opportunities to expose their pianistic and composing virtuosity (if they didn't demand the opportunities outright), both on concert stages as well as in the many music salons of the wealthy. Think about such giants as Anton Rubinstein, Jan Paderewski, Josef Hoffmann, Theodor Leschetizky, Vladimir Horowitz, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Ferruccio Busoni and Ignaz Friedman. The era of that other great piano virtuoso, Franz Liszt, was actually not even properly past. Liszt, after all, only returned from his last, very successful, but long and exhausting concert tour in the summer of 1886. The tour, through England and France, most likely did him in. (He died shortly afterwards, on the 31st of July 1886, at the age of seventy-four). Leopold Godowsky Godowsky's contemporaries called him the 'Buddha' of the piano, and he left a legacy of more than four hundred compositions, which make it crystal-clear that he knew the piano inside and out. Even more impressive, he shows in his compositions that as far as the technique of playing he had more mastery than his great contemporary Rachmaninoff, which clearly means something! It was by the way the very same Rachmaninoff who saw in Godowsky the only musician that made a lasting contribution to the development of the piano. -

The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes In

THE USE OF THE POLISH FOLK MUSIC ELEMENTS AND THE FANTASY ELEMENTS IN THE POLISH FANTASY ON ORIGINAL THEMES IN G-SHARP MINOR FOR PIANO AND ORCHESTRA OPUS 19 BY IGNACY JAN PADEREWSKI Yun Jung Choi, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Jeffrey Snider, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Choi, Yun Jung, The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes in G-sharp Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 19 by Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2007, 105 pp., 5 tables, 65 examples, references, 97 titles. The primary purpose of this study is to address performance issues in the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, by examining characteristics of Polish folk dances and how they are incorporated in this unique work by Paderewski. The study includes a comprehensive history of the fantasy in order to understand how Paderewski used various codified generic aspects of the solo piano fantasy, as well as those of the one-movement concerto introduced by nineteenth-century composers such as Weber and Liszt. Given that the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, as well as most of Paderewski’s compositions, have been performed more frequently in the last twenty years, an analysis of the combination of the three characteristic aspects of the Polish Fantasy, Op.19 - Polish folk music, the generic rhetoric of a fantasy and the one- movement concerto - would aid scholars and performers alike in better understanding the composition’s engagement with various traditions and how best to make decisions about those traditions when approaching the work in a concert setting. -

OWN BRAND Many Great Composers Are Decent Pianists, but Great Pianists Who Write Substantially for Themselves to Perform Tend to Be Taken Less Seriously As Composers

PIANIST-COMPOSERS OWN BRAND Many great composers are decent pianists, but great pianists who write substantially for themselves to perform tend to be taken less seriously as composers. Benjamin Ivry celebrates the achievements of these pianist-composers, and highlights some works that throw light on their inspiration and artistry at the keyboard OMPOSERS WHO PLAY THE PIANO FOR PRACTICAL recognised composer/orator/statesman as well as pianist, Liszt purposes and pianists who write music from inner pupil Emil von Sauer (1862-1942) produced the witty miniature necessity are different beings: composer-pianists and Music Box (Boîte à musique), catnip for such performers as Karol Cpianist-composers. If we disqualify pieces by those principally Szreter (although rather more po-faced in Sauer’s own recording). known asc composers, glitzy display works, and didactic études, Sauer’s Aspen Leaf (Espenlaub) is a more earnest assertion of music written by pianist-composers can be compelling and humanity, better suited to the pianist’s temperament, like the sometimes overlooked, perhaps in part because they are not taken elegant nostalgia of his Echo from Vienna (Echo aus Wien) and so seriously as those by full-time composers. Concert Galop, giving the impression that Sauer had witnessed Unlike the authors of most compositions performed in concert, the can-can being danced in French estaminets during the pianist-composers are alive and present, adding vivacity to the Belle Époque. occasion. Recitals can become uniquely personal statements. In Unlike the massive landscape of Carnaval de Vienne by Moriz the 19th century, Clara Schumann (1819-1896) wrote a Piano Rosenthal (1862-1946), an arrangement of Johann Strauss, Trio, Op 17 (1846) that is an ardent triangular conversation. -

Phd April 2019 Pp

The University of Adelaide Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts Revisiting George Enescu’s 1921 Bucharest Recital Series: a performance-based investigation with recordings and exegesis. by Elizabeth Layton submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Adelaide, April 2019 Table of Contents Abstract 5 Declaration 6 Acknowledgements 7 List of Musical Examples 8 List of Tables 11 Introduction 12 PART A: Sound recordings 22 A.1 CD 1 Tracks 1-4 Pierre de Bréville, Sonata no. 1 in C # minor 39:17 Tracks 5-8 Gabriel Fauré, Sonata no. 1 in A major, Op. 13 26:14 A.2 CD 2 Tracks 1-4 André Gédalge, Sonata no. 1 in G major, Op. 12 23:39 Tracks 5-7 Claude Debussy, Sonata in G minor (performance 1) 13:44 Tracks 8-10 Claude Debussy, Sonata in G minor (performance 2) 13:36 A.3 CD 3 Tracks 1-3 Ferruccio Busoni, Sonata no. 2 in E minor, Op. 36a 34:25 Tracks 4-7 Zygmunt Stojowski, Sonata no. 2 in E minor, Op. 37 29:30 A.4 CD 4 Tracks 1-4 Louis Vierne, Sonata in G minor, Op. 23 32:44 Tracks 5-7 Stan Golestan, Sonata in E flat major 26:56 Tracks 8-10 George Enescu, Sonata in F minor, Op. 6 22:34 PART B: Exegesis Chapter 1 George Enescu: Musician, and his path to the 1921 Bucharest Recital Series 27 1.1 Understanding the context and motivation behind the series 35 2 Chapter 2 The 1921 Bucharest Recital Series 38 2.1 Recital 1: Haydn, d’Indy, Bertelin 38 2.2 Recital 2: Mozart, Busoni, Vierne 39 2.3 Recital 3: Sjögren, Schubert, Lauweryns 41 2.4 Recital 4: Weingartner, Stojowski, Beethoven 42 2.5 Recital 5: Bargiel, Haydn, Golestan 42 2.6 Recital 6: Le Boucher, Mozart, Saint-Saëns 43 2.7 Recital 7: Gédalge, Dvorák, Debussy, Schumann 44 2.8 Recital 8: Huré, Bach, Lekeu 45 2.9 Recital 9: Beethoven, Fauré, Franck 46 2.10 Recital 10: Gallon, de Bréville, Beethoven 48 2.11 Recital 11: Magnard, Le Flem, Brahms 49 2.12 Recital 12: Franck, Enescu, Beethoven 49 Chapter 3 Performance notes on nine sonatas selected from the 1921 Bucharest Recital Series 3.1 Pierre de Bréville, Sonata no. -

The Baton: Vol. 8, No. 7

Published by THE INSTITUTE OF MUSICAL ART OF THE JUILLIARD SCHOOL OF MUSIC FRANK DAMROSCH, DEAN Vol. VIII, No. 7 15 CENTS A COPY THE BATON THE BATON endeavors to recommend the operas, concerts and recitals of especial worth and interest to music students. Appearances of faculty members, alumni and pupils arc featured FORTISSIMO in these columns. BEFORE THE PUBLIC EORGE A. WEDGE, who was in charge of music, so gloriously rendered. And if you are only the annual Alumni concert held this year on one-quarter part as glad to see me as I am to see e April 29th at the Institute, is to be hailed as you, I am fully content. the stage manager of a very enjoyable evening. The When I wrote to Dr. Damrosch a few days ago Musical Art Quartet played the Beethoven Quartet to inform him of my impending visit, I begged him in G major and the Debussy Quartet in G minor. to keep it a secret. I gave a number of humbug ex- Dr. Damrosch told of plans for a new building to cuses for this, but what I really meant was that if be begun soon in our block which will be the home it became generally known that I was to be here, of both the Juilliard Graduate School and the Insti- not a soul would come here—and that would not have tute of Musical Art. It will please all those who are suited me at all, for I wanted you to be here so that or have been students here to know that our Recital I could see you. -

S Twenty-Fourth Caprice, Op. 1 by Busoni, Friedman, and Muczynski

AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE VARIATIONS ON THE THEME OF PAGANINI’S TWENTY-FOURTH CAPRICE, OP. 1 BY BUSONI, FRIEDMAN, AND MUCZYNSKI, A LECTURE RECITAL, TOGETHER WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS BY BACH, BEETHOVEN, CHOPIN, DEBUSSY, HINDEMITH, KODÁLY, PROKOFIEV, SCRIABIN, AND SILOTI Kwang Sun Ahn, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2000 APPROVED: Joseph Banowetz, Major Professor Gene J. Cho, Minor Professor Steven Harlos, Committee Member Adam J. Wodnicki, Committee Member William V. May, Dean of the College of Music C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Ahn, Kwang Sun, An Analytical Study of the Variations on the Theme of Paganini’s Twenty-fourth Caprice, Op. 1 by Busoni, Friedman, and Muczynski. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2000, 94 pp., 66 examples, 9 tables, bibliography, 71 titles. The purpose of this study is to analyze sets of variations on Paganini’s theme by three twentieth-century composers: Ferruccio Busoni, Ignaz Friedman, and Robert Muczynski, in order to examine, identify, and trace different variation techniques and their applications. Chapter 1 presents the purpose and scope of this study. Chapter 2 provides background information on the musical form “theme and variations” and the theme of Paganini’s Twenty-fourth Caprice, Op. 1. Chapter 2 also deals with the question of which elements have made this theme so popular. Chapters 3,4, and 5 examine each of the three sets of variations in detail using the following format: theme, structure of each variation, harmony and key, rhythm and meter, tempo and dynamics, motivic development, grouping of variations, and technical problems. -

Download Booklet

110690 bk Friedman3 EC 5|12|02 3:35 PM Page 5 Ignaz Friedman 8 Mazurka, Op. 7, No. 2 in A minor 2:30 Appendix: ADD Complete Recordings, Volume 3 ( Friedman speaks on Chopin 5:11 English Columbia 1928-1930 9 Mazurka, Op. 33, No. 2 in D major 2:04 Recorded November 1940 Great Pianists • Friedman 8.110690 Recorded 13th September 1930 New Zealand Radio transcription disc 1928 Matrix 5211-5 (Catalogue LX99) Gluck/Brahms: Discographic information taken from 1 Gavotte 2:47 0 Mazurka, Op. 33, No. 4 in B minor 4:08 “Ignaz Friedman: A Discography, Part 1”, Recorded 9th February 1928 Recorded 13th September 1930 compiled by D.H. Mason and Gregor Benko. CHOPIN Matrix WA6943-1 (Catalogue D1651) Matrix 5209-5 (Catalogue LX100) Please thank: Donald Manildi and Gluck/Friedman: ! Mazurka, Op. 24, No. 4 in B flat major 3:44 Raymond Edwards. Mazurkas 2 Menuet (Judgement of Paris) 2:55 Recorded 13th September 1930 Recorded 10th February 1928 Matrix 5208-6 (Catalogue LX100) Polonaise in B flat Matrix WA6945-2 (Catalogue D1640) @ Mazurka, Op. 41, No. 1 in C sharp minor 3:02 Schubert/Liszt: Recorded 10th October 1929 3 Hark, hark, the lark 2:55 Matrix 5207-2 Recorded 10th February 1928 (issued only in U.S. Catalogue 67950) SCHUBERT Matrix WA6947-1 (Catalogue D1636) # Mazurka, Op. 41, No. 1 in C sharp minor 3:00 Hark, hark the lark Schubert/Friedman: Recorded 17th September 1930 4 Alt Wien 7:08 Matrix 5207-9 (Catalogue LX101) Recorded 2nd March 1928 Alt Wien Matrix WAX3341-1, 3342-2 (Catalogue L2107) $ Mazurka, Op. -

2Nd Stanisław Moniuszko International Competition of Polish Music

2nd Stanisław Moniuszko International Competition of Polish Music Konkurs należy do organizacji Alink-Argerich Foundation program 2 11–18 WRZEŚNIA 2021 II Międzynarodowy Konkurs Muzyki Polskiej im. Stanisława Moniuszki 11–18 września 2021 roku II Międzynarodowy Konkurs Muzyki Polskiej im. Stanisława Moniuszki 11–18 września 2021 roku Misja i cele Konkursu Celem Międzynarodowego Konkursu Muzyki Polskiej im. Stanisła- wa Moniuszki jest popularyzacja polskiej muzyki na świecie oraz utrwalenie w świadomości odbiorców znaczenia twórczości zarówno Stanisława Moniuszki, jak i wielu wybitnych polskich kompozytorów. Konkurs promuje dorobek muzyki polskiej XIX i XX wieku, zwłaszcza tej, która została zapomniana lub jest mniej popularna w praktyce koncertowej. Ma się przyczynić do tego, by szeroka publiczność poznała na nowo odkrywane utwory, a niesłusznie zaniedbana spuścizna doczekała się należytego opracowania i nowych edycji. Równie ważnym celem konkursu jest promowanie utalentowanych muzyków, którzy zdecydują się włączyć do swojego repertuaru mniej znane dzieła polskich kompozytorów. Organizacja konkursu to tak- że promocja Polski jako miejsca, gdzie odbywają się wydarzenia artystyczne o międzynarodowym zasięgu. Podstawowe założenia Konkurs odbywa się co dwa lata i może być przeznaczony dla róż- nych składów wykonawczych. Druga edycja konkursu odbędzie się w dwóch kategoriach – fortepian i zespoły kameralne. W kon- kursie mogą uczestniczyć muzycy-instrumentaliści zgłaszający się indywidualnie oraz jako zespoły kameralne (od duetów po składy dwunastoosobowe). W konkursie nie ma ograniczeń ze względu na wiek i obywatelstwo uczestników. II MIĘDZYNARODOWY KONKURS MUZYKI POLSKIEJ 5 Uczestnicy będą prezentować utwory 56 polskich kompozytorów, tworzących głównie w XIX i XX wieku. Przesłuchania konkursowe odbędą się w Filharmonii Podkarpackiej im. Artura Malawskiego w Rzeszowie od 11 do 18 września 2021 roku.