Cultural Evolution in the Eurasian Tree Sparrow: Divergence Between

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mt. Tabor Park Breeding Bird Survey Results 2009

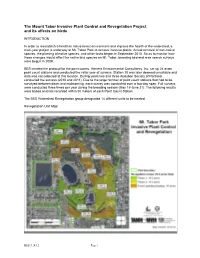

The Mount Tabor Invasive Plant Control and Revegetation Project and its affects on birds INTRODUCTION In order to reestablish a healthier native forest environment and improve the health of the watershed, a multi-year project is underway at Mt. Tabor Park to remove invasive plants. Actual removal of non-native species, the planting of native species, and other tasks began in September 2010. So as to monitor how these changes would affect the native bird species on Mt. Tabor, breeding bird and area search surveys were begun in 2009. BES created the protocol for the point counts. Herrera Environmental Consultants, Inc. set up 24 avian point count stations and conducted the initial year of surveys. Station 10 was later deemed unsuitable and data was not collected at this location. During years two and three Audubon Society of Portland conducted the surveys (2010 and 2011). Due to the large number of point count stations that had to be surveyed between dawn and midmorning, each survey was conducted over a two-day span. Full surveys were conducted three times per year during the breeding season (May 15-June 31). The following results were based on birds recorded within 50 meters of each Point Count Station. The BES Watershed Revegetation group designated 14 different units to be treated. Revegetation Unit Map: BES 3.14.12 Page 1 Point Count Station Location Map: The above map was created by Herrera and shows where the point count stations are located. Point Count Stations are fairly evenly dispersed around Mt. Tabor in a variety of habitats. -

Innovative Foraging by the House Sparrow Passer Domesticus

46 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2005, 22, 46--47 Innovative Foraging by the House Sparrow Passer domesticus NEIL SHELLEY 16 Birdrock Avenue, Mount Martha, Victoria 3934 (Email: [email protected]) Summary This note describes an incidental observation of House Sparrows Passer domesticus foraging for insects trapped within the engine bay of motor vehicles in south-eastern Australia. Introduction The House Sparrow Passer domesticus is commensal with man and its global range has increased significantly recently, closely following human settlement on most continents and many islands (Long 1981, Cramp 1994). It is native to Eurasia and northern Africa (Cramp 1994) and was introduced to Australia in the mid 19th century (Biakers et al. 1984, Schodde & Tidemann 1997, Pizzey & Knight 1999). It is now common in cities and towns throughout eastern Australia (Biakers et al. 1984, Schodde & Tidemann 1997, Pizzey & Knight 1999, Barrett et al. 2003), particularly in association with human habitation (Schodde & Tidemann 1997), but is decreasing nationally (Barrett et al. 2003). Observation On 13 January 2003 at c. 1745 h Eastern Summer Time, a small group of House Sparrows was observed foraging in the street outside a restaurant in Port Fairy, on the south-western coast of Victoria (38°23' S, 142°14' E). Several motor vehicles were angle-parked in the street, nose to the kerb, adjacent to the restaurant. The restaurant had a few tables and chairs on the footpath for outside dining. The Sparrows appeared to be foraging only for food scraps, when one of them entered the front of a parked vehicle and emerged shortly after with an insect, which it then consumed. -

An Annotated List of Birds Wintering in the Lhasa River Watershed and Yamzho Yumco, Tibet Autonomous Region, China

FORKTAIL 23 (2007): 1–11 An annotated list of birds wintering in the Lhasa river watershed and Yamzho Yumco, Tibet Autonomous Region, China AARON LANG, MARY ANNE BISHOP and ALEC LE SUEUR The occurrence and distribution of birds in the Lhasa river watershed of Tibet Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China, is not well documented. Here we report on recent observations of birds made during the winter season (November–March). Combining these observations with earlier records shows that at least 115 species occur in the Lhasa river watershed and adjacent Yamzho Yumco lake during the winter. Of these, at least 88 species appear to occur regularly and 29 species are represented by only a few observations. We recorded 18 species not previously noted during winter. Three species noted from Lhasa in the 1940s, Northern Shoveler Anas clypeata, Solitary Snipe Gallinago solitaria and Red-rumped Swallow Hirundo daurica, were not observed during our study. Black-necked Crane Grus nigricollis (Vulnerable) and Bar-headed Goose Anser indicus are among the more visible species in the agricultural habitats which dominate the valley floors. There is still a great deal to be learned about the winter birds of the region, as evidenced by the number of apparently new records from the last 15 years. INTRODUCTION limited from the late 1940s to the early 1980s. By the late 1980s the first joint ventures with foreign companies were The Lhasa river watershed in Tibet Autonomous Region, initiated and some of the first foreign non-governmental People’s Republic of China, is an important wintering organisations were allowed into Tibet, enabling our own area for a number of migratory and resident bird species. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Phylogeography of Finches and Sparrows

In: Animal Genetics ISBN: 978-1-60741-844-3 Editor: Leopold J. Rechi © 2009 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 1 PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF FINCHES AND SPARROWS Antonio Arnaiz-Villena*, Pablo Gomez-Prieto and Valentin Ruiz-del-Valle Department of Immunology, University Complutense, The Madrid Regional Blood Center, Madrid, Spain. ABSTRACT Fringillidae finches form a subfamily of songbirds (Passeriformes), which are presently distributed around the world. This subfamily includes canaries, goldfinches, greenfinches, rosefinches, and grosbeaks, among others. Molecular phylogenies obtained with mitochondrial DNA sequences show that these groups of finches are put together, but with some polytomies that have apparently evolved or radiated in parallel. The time of appearance on Earth of all studied groups is suggested to start after Middle Miocene Epoch, around 10 million years ago. Greenfinches (genus Carduelis) may have originated at Eurasian desert margins coming from Rhodopechys obsoleta (dessert finch) or an extinct pale plumage ancestor; it later acquired green plumage suitable for the greenfinch ecological niche, i.e.: woods. Multicolored Eurasian goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) has a genetic extant ancestor, the green-feathered Carduelis citrinella (citril finch); this was thought to be a canary on phonotypical bases, but it is now included within goldfinches by our molecular genetics phylograms. Speciation events between citril finch and Eurasian goldfinch are related with the Mediterranean Messinian salinity crisis (5 million years ago). Linurgus olivaceus (oriole finch) is presently thriving in Equatorial Africa and was included in a separate genus (Linurgus) by itself on phenotypical bases. Our phylograms demonstrate that it is and old canary. Proposed genus Acanthis does not exist. Twite and linnet form a separate radiation from redpolls. -

Goldfinches and Finch Food!

A Purple Finch (left) en- Frequently Asked Questions joys Sunflower Hearts and About Finch FOOD: an American goldfinch (right, in winter plumage) B i r d s - I - V i e w munches on a 50/50 blend Q. What do Finches eat? of Sunflower heart chips A. Finches utilize many small grass seeds and and Nyjer Seed . flower seed in nature and are built to shell tiny Frequently Asked Questions seeds easily. At Backyard Bird feeders they will Q. Do Goldfinches migrate in winter? FAQ consume Nyjer Seed (traditionally referred to as A. In much of the US, including the Mid- “thistle” in the bird feeding industry, but now west, Goldfinch are year-round residents. about more correctly referred to as “Nyjer”). They also There are areas of the US that only experi- consume Black Oil sunflower Seed and LOVE ence Goldfinch in the Winter and parts of Goldfinches and Sunflower HEARTS whether whole or in fine northern US and Canada only have them chips. In recent years, more and more backyard during breeding season. Check out the nota- Finch Food! birders are feeding Sunflower hearts (which ble difference between the Goldfinch’s does not have a shell) either alone or combined plumage in the winter and during breeding with the traditional Nyjer seed (which DOES season on the cover of this brochure! Q. What other finches can I see at feeders used by Goldfinch? A. Year-round House Finch as well as non- finch family birds like chickadees, tufted Titmouse, and Downy Woodpecker will en- joy your finch feeder. -

International Studies on Sparrows

1 ISBN 1734-624X INSTITUTE OF BIOTECHNOLOGY & ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION, UNIVERSITY OF ZIELONA GÓRA INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR ECOLOGY WORKING GROUP ON GRANIVOROUS BIRDS – INTECOL INTERNATIONAL STUDIES ON SPARROWS Vol. 30 University of Zielona Góra Zielona Góra 2 Edited by Working Group on Granivorous Birds – INTECOL Editor: Prof. Dr. Jan Pinowski (CES PAS) Co-editors: Prof. Dr. David T. Parkin (Queens Med. Centre, Nottingham), Dr. hab. Leszek Jerzak (University of Zielona Góra), Dr. hab. Piotr Tryjanowski (University of Poznań) Ass. Ed.: M. Sc. Andrzej Haman (CES PAS) Address to Editor: Prof. Dr. Jan Pinowski, ul. Daniłowskiego 1/33, PL 01-833 Warszawa e-mail: [email protected] “International Studies on Sparrows” since 1967 Address: Institute of Biotechnology & Environmental Protection University of Zielona Góra ul. Monte Cassino 21 b, PL 65-561 Zielona Góra e-mail: [email protected] (Financing by the Institute of Biotechnology & Environmental Protection, University of Zielona Góra) 3 CONTENTS Preface ................................................................................................. 5 1. Andrei A. Bokotey, Igor M. Gorban – Numbers, distribution, ecology of and the House Sparrow in Lvov (Ukraine) ...................... 7 2. J. Denis Summers-Smith – Changes in the House Sparrow population in Britain ...................................................................... 23 3. Marcin Bocheński – Nesting of the sparrows Passer spp. in the White Stork Ciconia ciconia nests in a stork colony in Kłopot (W Poland) .................................................................... 39 5 PREFACE The Institute of Ecology of the Polish Academy of Science has financed the journal “International Studies on Sparrow”. Unfortunately, publica- tion was liquidated for financial reasons. The Editing Board had prob- lems continuing with the last journal. Thanks to a proposal for editing and financing the “ISS” from the Institute of Biotechnology and Environmental Protection UZ, the journal will now be edited by University of Zielona Góra beginning in 2005. -

House Sparrow

House Sparrow Passer domesticus Description FUN FACTS The House Sparrow is a member of the Old World sparrow family native to most of The House Sparrow is part of the weaver Europe and Asia. This little bird has fol- finch family of birds which is not related lowed humans all over the world and has to North American native sparrows. been introduced to every continent ex- cept Antarctica. In North America, the birds were intentionally introduced to the These birds have been in Alberta for United States from Britain in the 1850’s as about 100 years, making themselves at they were thought to be able to help home in urban environments. with insect control in agricultural crops. Being a hardy and adaptable little bird, the House Sparrow has spread across the continent to become one of North Amer- House Sparrows make untidy nests in ica’s most common birds. However, in many different locales and raise up to many places, the House Sparrow is con- three broods a season. sidered to be an invasive species that competes with, and has contributed to the decline in, certain native bird spe- These birds usually travel, feed, and roost cies. The males have a grey crown and in assertive, noisy, sociable groups but underparts, white cheeks, a black throat maintain wariness around humans. bib and black between the bill and eyes. Females are brown with a streaked back (buff, black and brown). If you find an injured or orphaned wild ani- mal in distress, please contact the Calgary Wildlife Rehabilitation Society hotline at 403- 214-1312 for tips, instructions and advice, or visit the website for more information www.calgarywildlife.org Photo Credit: Lilly Hiebert Contact Us @calgarywildlife 11555—85th Street NW, Calgary, AB T3R 1J3 [email protected] @calgarywildlife 403-214-1312 calgarywildlife.org @Calgary_wildlife . -

Lhasa and the Tibetan Plateau Cumulative

Lhasa and the Tibetan Plateau Cumulative Bird List Column A: Total number of tours (out of 6) that the species was recorded Column B: Total number of days that the species was recorded on the 2016 tour Column C: Maximum daily count for that particular species on the 2016 tour Column D: H = Heard Only; (H) = Heard more than seen Globally threatened species as defined by BirdLife International (2004) Threatened birds of the world 2004 CD-Rom Cambridge, U.K. BirdLife International are identified as follows: EN = Endangered; VU = Vulnerable; NT = Near- threatened. A B C D 6 Greylag Goose 2 15 Anser anser 6 Bar-headed Goose 4 300 Anser indicus 3 Whooper Swan 1 2 Cygnus cygnus 1 Common Shelduck Tadorna tadorna 6 Ruddy Shelduck 8 700 Tadorna ferruginea 3 Gadwall 2 3 Anas strepera 1 Eurasian Wigeon Anas penelope 5 Mallard 2 8 Anas platyrhynchos 2 Eastern Spot-billed Duck Anas zonorhyncha 1 Indian or Eastern Spot-billed Duck Anas poecilorhynchos or A. zonorhyncha 1 Northern Shoveler Anas clypeata 1 Northern Pintail Anas acuta 1 Garganey 2 15 Anas querquedula 4 Eurasian Teal 2 50 Anas crecca 6 Red-crested Pochard 3 2000 Netta rufina 6 Common Pochard 2 200 Aythya ferina 3 Ferruginous Duck NT 1 8 Aythya nyroca 6 Tufted Duck 2 200 Aythya fuligula 5 Common Goldeneye 2 11 Bucephala clangula 4 Common Merganser 3 51 Mergus merganser 5 Chinese Grouse NT 2 1 Tetrastes sewerzowi 4 Verreaux's Monal-Partridge 1 1 H Tetraophasis obscurus 5 Tibetan Snowcock 1 5 H Tetraogallus tibetanus 4 Przevalski's Partridge 1 1 Alectoris magna 1 Daurian Partridge Perdix dauurica 6 Tibetan Partridge 2 11 Perdix hodgsoniae ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. -

First Records of the Common Chaffinch Fringilla Coelebs and European Greenfinch Carduelis Chloris from Lord Howe Island

83 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2004, 2I , 83- 85 First Records of the Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and European Greenfinch Carduelis chloris from Lord Howe Island GLENN FRASER 34 George Street, Horsham, Victoria 3400 Summary Details are given of the first records of two species of finch from Lord Howe Island: the Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and the European Greenfinch Carduelis chloris. These records, from the early 1980s, have been quoted in several papers without the details hav ing been published. My Common Chaffinch records are the first for the species in Australian territory. Details of my records and of other published records of other European finch es on Lord Howe Island are listed, and speculation is made on the origin of these finches. Introduction This paper gives details of the first records of the Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and the European Greenfinch Carduelis chloris for Lord Howe Island. The Common Chaffinch records are the first for any Australian territory and although often quoted (e.g. Boles 1988, Hutton 1991, Christidis & Boles 1994), the details have not yet been published. Other finches, the European Goldfinch C. carduelis and Common Redpoll C. fiammea, both rarely reported from Lord Howe Island, were also recorded at about the same time. Lord Howe Island (31 °32'S, 159°06'E) lies c. 800 km north-east of Sydney, N.S.W. It is 600 km from the nearest landfall in New South Wales, and 1200 km from New Zealand. Lord Howe Island is small (only 11 km long x 2.8 km wide) and dominated by two mountains, Mount Lidgbird and Mount Gower, the latter rising to 866 m above sea level. -

The Relationships of the Hawaiian Honeycreepers (Drepaninini) As Indicated by Dna-Dna Hybridization

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE HAWAIIAN HONEYCREEPERS (DREPANININI) AS INDICATED BY DNA-DNA HYBRIDIZATION CH^RrES G. SIBLEY AND Jo• E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--Twenty-twospecies of Hawaiian honeycreepers(Fringillidae: Carduelinae: Drepaninini) are known. Their relationshipsto other groups of passefineswere examined by comparing the single-copyDNA sequencesof the Apapane (Himationesanguinea) with those of 5 speciesof carduelinefinches, 1 speciesof Fringilla, 15 speciesof New World nine- primaried oscines(Cardinalini, Emberizini, Thraupini, Parulini, Icterini), and members of 6 other families of oscines(Turdidae, Monarchidae, Dicaeidae, Sylviidae, Vireonidae, Cor- vidae). The DNA-DNA hybridization data support other evidence indicating that the Hawaiian honeycreepersshared a more recent common ancestorwith the cardue!ine finches than with any of the other groupsstudied and indicate that this divergenceoccurred in the mid-Miocene, 15-20 million yr ago. The colonizationof the Hawaiian Islandsby the ancestralspecies that radiated to produce the Hawaiian honeycreeperscould have occurredat any time between 20 and 5 million yr ago. Becausethe honeycreeperscaptured so many ecologicalniches, however, it seemslikely that their ancestor was the first passefine to become established in the islands and that it arrived there at the time of, or soon after, its separationfrom the carduelinelineage. If so, this colonist arrived before the present islands from Hawaii to French Frigate Shoal were formed by the volcanic"hot-spot" now under the island of Hawaii. Therefore,the ancestral drepaninine may have colonizedone or more of the older Hawaiian Islandsand/or Emperor Seamounts,which also were formed over the "hot-spot" and which reachedtheir present positions as the result of tectonic crustal movement. -

Factors Influencing Numbers of Syntopic House Sparrows and Eurasian Tree Sparrows on Farms

382 ShortCommunications and Commentaries [Auk, Vol. 110 The Auk 110(2):382-385, 1993 Factors Influencing Numbers of Syntopic House Sparrows and Eurasian Tree Sparrows on Farms PEDROJ. CORDERO InstitutoPirenaico de Ecologœa,Consejo Superior de InvestigacionesCient•ficas, Apartado202, 50080 Zaragoza,Spain The House Sparrow(Passer domesticus) and the Eur- was mappedand classifiedinto agriculturalland, in- asianTree Sparrow(P. montanus)show differencesin cluding: (FORAGE)orchards, cereals and associated habitat use. The former is predominantly an urban natural vegetationwhere sparrowsforaged; (FOR- and suburbanspecies, while the EurasianTree Spar- EST)woodlands, including Mediterranean oak, pine row is more rural (Summers-Smith 1963, Pinowski forestand Mediterranean scrub;and (GARDEN) gar- 1967, Lack 1971, Cody 1974, Dyer et al. 1977). How- dens, including groves of several tree speciesand ever, they often coexistalong suburban-ruralgradi- ornamentalshrubs where the sparrowsdid not forage. ents (Cody 1974), where extensivediet overlap (An- Open fields supportedagricultural activities, mostly derson1978, 1984) and nest-sitesegregation (Anderson intensivevegetable growing (89%),with the rest in 1978,Cordero and Rodriguez-Teijeiro1990) have been alfalfa, wheat, barley and maize. found. Some ecological(Pinowski 1967, Anderson To evaluate livestock I considered cattle equiva- 1978)and geographical(Summers-Smith 1963, 1988) lents of domestic animal biomass (LIVESIND; Table evidence suggeststhat habitat differences,in part, 1). To obtain this, total