International Studies on Sparrows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House Sparrow

House Sparrow Passer domesticus Description FUN FACTS The House Sparrow is a member of the Old World sparrow family native to most of The House Sparrow is part of the weaver Europe and Asia. This little bird has fol- finch family of birds which is not related lowed humans all over the world and has to North American native sparrows. been introduced to every continent ex- cept Antarctica. In North America, the birds were intentionally introduced to the These birds have been in Alberta for United States from Britain in the 1850’s as about 100 years, making themselves at they were thought to be able to help home in urban environments. with insect control in agricultural crops. Being a hardy and adaptable little bird, the House Sparrow has spread across the continent to become one of North Amer- House Sparrows make untidy nests in ica’s most common birds. However, in many different locales and raise up to many places, the House Sparrow is con- three broods a season. sidered to be an invasive species that competes with, and has contributed to the decline in, certain native bird spe- These birds usually travel, feed, and roost cies. The males have a grey crown and in assertive, noisy, sociable groups but underparts, white cheeks, a black throat maintain wariness around humans. bib and black between the bill and eyes. Females are brown with a streaked back (buff, black and brown). If you find an injured or orphaned wild ani- mal in distress, please contact the Calgary Wildlife Rehabilitation Society hotline at 403- 214-1312 for tips, instructions and advice, or visit the website for more information www.calgarywildlife.org Photo Credit: Lilly Hiebert Contact Us @calgarywildlife 11555—85th Street NW, Calgary, AB T3R 1J3 [email protected] @calgarywildlife 403-214-1312 calgarywildlife.org @Calgary_wildlife . -

Natural Epigenetic Variation Within and Among Six Subspecies of the House Sparrow, Passer Domesticus Sepand Riyahi1,*,‡, Roser Vilatersana2,*, Aaron W

© 2017. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2017) 220, 4016-4023 doi:10.1242/jeb.169268 RESEARCH ARTICLE Natural epigenetic variation within and among six subspecies of the house sparrow, Passer domesticus Sepand Riyahi1,*,‡, Roser Vilatersana2,*, Aaron W. Schrey3, Hassan Ghorbani Node4,5, Mansour Aliabadian4,5 and Juan Carlos Senar1 ABSTRACT methylation is one of several epigenetic processes (such as histone Epigenetic modifications can respond rapidly to environmental modification and chromatin structure) that can influence an ’ changes and can shape phenotypic variation in accordance with individual s phenotype. Many recent studies show the relevance environmental stimuli. One of the most studied epigenetic marks is of DNA methylation in shaping phenotypic variation within an ’ DNA methylation. In the present study, we used the methylation- individual s lifetime (e.g. Herrera et al., 2012), such as the effect of sensitive amplified polymorphism (MSAP) technique to investigate larval diet on the methylation patterns and phenotype of social the natural variation in DNA methylation within and among insects (Kucharski et al., 2008). subspecies of the house sparrow, Passer domesticus. We focused DNA methylation is a crucial process in natural selection on five subspecies from the Middle East because they show great and evolution because it allows organisms to adapt rapidly to variation in many ecological traits and because this region is the environmental fluctuations by modifying phenotypic traits, either probable origin for the house sparrow’s commensal relationship with via phenotypic plasticity or through developmental flexibility humans. We analysed house sparrows from Spain as an outgroup. (Schlichting and Wund, 2014). -

Download Report

BTO Research Report 384 The London Bird Project Authors Dan Chamberlain, Su Gough, Howard Vaughan, Graham Appleton, Steve Freeman, Mike Toms, Juliet Vickery, David Noble A report to The Bridge House Estates Trust January 2005 © British Trust for Ornithology British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk IP24 2PU Registered Charity No. 216652 British Trust for Ornithology The London Bird Project BTO Research Report No. 384 Dan Chamberlain, Su Gough, Howard Vaughan, Graham Appleton, Steve Freeman, Mike Toms, Juliet Vickery, David Noble Published in January 2005 by the British Trust for Ornithology The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk, IP24 2PU, UK Copyright © British Trust for Ornithology 2005 ISBN 1-904870-18-X All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables .........................................................................................................................................3 List of Figures........................................................................................................................................5 List of Appendices.................................................................................................................................7 Executive Summary ..............................................................................................................................9 -

Correspondence Seen on 31 January 2020, During the Annual Bird Census of Pong Lake (Ranganathan 2020), and Eight on 16 February 2020 (Sharma 2020)

150 Indian BIRDS VOL. 16 NO. 5 (PUBL. 26 NOVEMBER 2020) photographs [142]. At the same place, 15 Sind Sparrows were Correspondence seen on 31 January 2020, during the Annual Bird Census of Pong Lake (Ranganathan 2020), and eight on 16 February 2020 (Sharma 2020). About one and a half kilometers from this place (31.97°N, 75.89°E), I recorded two males and one female Sind The status of the Sind Sparrow Passer pyrrhonotus, Sparrow, feeding on a village road, on 09 March 2020. When Spanish Sparrow P. hispaniolensis, and Eurasian Tree disturbed they took cover in nearby Lantana sp., scrub [143]. Sparrow P. montanus in Himachal Pradesh On 08 August 2020, Piyush Dogra and I were birding on the Five species of Passer sparrows are found in the Indian opposite side of Shah Nehar Barrage Lake (31.94°N, 75.91°E). Subcontinent. These are House Sparrow Passer domesticus, We saw and photographed three Sind Sparrows, sitting on a wire, Spanish Sparrow P. hispaniolensis, Sind Sparrow P. pyrrhonotus, near the reeds. Russet Sparrow P. cinnamomeus, and Eurasian Tree Sparrow P. montanus (Praveen et al. 2020). All of these, except the Sind Sparrow, have been reported from Himachal Pradesh (Anonymous 1869; Grimmett et al. 2011). The Russet Sparrow and the House Sparrow are common residents (den Besten 2004; Dhadwal 2019). In this note, I describe my records of the Sind Sparrow (first for the state) and Spanish Sparrows from Himachal Pradesh. I also compile other records of these three species from Himachal Pradesh. Sind Sparrow Passer pyrrhonotus On 05 February 2017, I visited Sthana village, near Shah Nehar Barrage, Kangra District, Himachal Pradesh, which lies close to C. -

The Use of Nest-Boxes by Two Species of Sparrows (Passer Domesticus and P

Intern. Stud. Sparrows 2012, 36: 18-29 Andrzej WĘGRZYNOWICZ Museum and Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Science Wilcza 64, 00-679 Warsaw e-mail: [email protected] THE USE OF NEST-BOXES BY TWO SPECIES OF SPARROWS (PASSER DOMESTICUS AND P. MONTANUS) WITH OPPOSITE TRENDS OF ABUNDANCE – THE STUDY IN WARSAW ABSTRACT The occupation of nest-boxes by House- and Tree Sparrow in Warsaw was investigated in 2005-2009 and in 2012 . Riparian forests, younger and older parks in downtown, and housing estates were included in the study as 4 types of habitats corresponding to the urbanization gradient of Warsaw . 1035 inspections of nest-boxes suitable for both spe- cies (type A) were carried out during the breeding period and 345 nest-boxes of other types were inspected after the breeding period . In order to determine the importance of nest-boxes for both species on different plots, obtained data were analyzed using Nest-box Importance Coefficient (NIC) . This coefficient describes species-specific rate of occupation of nest-boxes as well as the contribution of the pairs nesting in them . Tree Sparrow occupied a total of 33% of A-type nest-boxes, its densities were positively correlated with the number of nest-boxes, and seasonal differences in occupation rate were low for this species . The NIC and the rate of nest-box occupation for Tree Sparrow decreased along an urbanization gradient . House Sparrow used nest-boxes very rarely, only in older parks and some housing estates . Total rate of nest-box occupation for House Sparrow in studied plots was 4%, and NIC was relatively low . -

The First Record of Yellow-Throated Sparrow Gymnoris Xanthocollis in Egypt MASSIMILIANO DETTORI & István Moldován

The first record of Yellow-throated Sparrow Gymnoris xanthocollis in Egypt MASSIMILIANO DETTORI & ISTVÁN MOLDOVÁN The Yellow-throated Sparrow Gymnoris xanthocollis breeds in southeast Turkey, through Iraq, Iran, United Arab Emirates, Oman, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India (Porter & Aspinall 2010, Rasmussen & Anderton 2005). It has been recorded as a vagrant, three records, in Israel (Perlman & Meyrav 2009). On 5 June 2010, on the Egyptian Red sea coast 17 km north of Marsa Alam city, while birding in the garden of Brayka Bay resort, MD noted a calling Yellow-throated Sparrow in the top of a palm tree (Google Earth GPS coordinates 25° 12’ 59.92” N 34° 47’ 58.23” E). The bird was easily detected as its continuous calling had brought it to the attention of MD. The call was very like that of a House Sparrow Passer domesticus, but because no House Sparrows had been seen or heard in the resort, MD investigated further. During the observation, the bird also uttered a guttural low-tone short song while perched on top of the tree. Through binoculars, the yellow throat-patch, chestnut-coloured feathers on the edge of the scapulars and white median-covert bar were immediately obvious, sufficiently so to identify the bird without any doubt as a Yellow-throated Sparrow. Regarding its behaviour, MD noted that it was very shy, but when its call was imitated by MD, the bird came closer to him and perched on a nearby eucalyptus tree. The bird was observed 07.10–07.30 h before it flew away. Next day (6 June) the bird was seen again at 07.45 h for 10 minutes. -

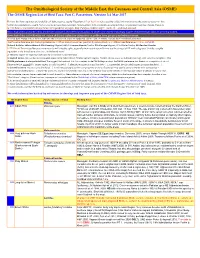

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

The House Sparrow Is Disappearing from Many of Our Cities and Towns

AKHILESH KUMAR, AMITA KANAUJIA, SONIKA KUSHWAHA AND ADESH KUMAR TORY S OVER C The House sparrow is disappearing from many of our cities and towns. We can resurrect their numbers by simple steps like providing alternative nesting sites for these little chirping birds. among the fi rst animals to develop a close surveys conducted by ornithologists and association with humans. This led it to researchers suggest that the dramatic HE gentle chirruping of the small bird being given the name Passer domesticus. decline in population of the sparrow is an Tis slowly vanishing. As the House The House sparrow is also commonly unfortunate reality. sparrow loses its living space to other known as Gauriya. Scientists and researchers aggressive birds and also to humans, it is Unfortunately, the species has been suggest several causes responsible disappearing in large parts of the world. declining since the early 1980s in several for the diminishing population like In the last few years the bird has gone parts of the world. There has also been unavailability of nesting space, decrease completely missing from most urban noticeable decline in the number of in food availability, changes in human neighbourhoods. House sparrows in several parts of India lifestyle, pollution, electromagnetic As humans settled down to particularly across Bangalore, Mumbai, radiation from mobile phone towers agriculture and set up permanent Hyderabad, Punjab, Haryana, West (obsolete theory now) and diseases. settlements, the House sparrow was Bengal, Delhi and other cities. Several -

House Sparrow Control

Fact Sheet: House Sparrow Control The North American Bluebird Society is providing this information on House Sparrow control to let you know that there are options available when dealing with sparrow problems. Given the widespread problems caused by House Sparrows, NABS advises that it is the responsibility of every nest box trail operator to ensure that no House Sparrows fledge from their boxes. It is better to have no nest box than to have one which fledges sparrows. HOUSE SPARROWS House Sparrows are the most abundant songbirds in North America and the most widely distributed birds on the planet. House Sparrows are not actually sparrows, but are Old World Weaver Finches, a family of birds noted for their ingenious nest-building abilities. HISTORY House Sparrows were introduced into North America from England in the 1850s on the mistaken premise that they would help reduce crop insect pests. At first, the new immigrants welcomed this little bird of their homeland. Within 25 years, however, they realized the seriousness of their mistake: the House Sparrow PASSIVE CONTROL population had increased at an explosive and alarming rate, and the birds were causing extensive damage to 1. BOX LOCATION crops and fruit trees. They were also taking over the Box location is the most crucial factor in controlling nesting sites of native cavity-nesting birds. sparrows on a bluebird trail. The House Sparrow's Latin name, Passer domesticus, aptly describes its LIFE AND HABITS preferred nesting habits - around houses. Avoid The breeding season for House Sparrows begins early placing boxes near farmsteads, feedlots, barns, old in the spring or even in midwinter, and each pair may out-buildings, etc. -

Sparrow, House

592 Old World Sparrows — Family Passeridae Old World Sparrows — Family Passeridae House Sparrow Passer domesticus No bird on earth is as completely a commensal of man as the House Sparrow. A native of Eurasia, it was introduced repeatedly from England to the United States in the 19th century, then transplant- ed within this country. Transplantation to San Francisco allowed the birds to spread to southern California; they arrived in San Diego in 1913 and quickly proliferated. Now few clusters of buildings of any consequence lack House Sparrows, but in southern California the birds seldom spread into undeveloped natural habitats. Breeding distribution: The House Sparrow’s distribution Photo by Anthony Mercieca in San Diego County follows the limits of built-up areas almost exactly. Even isolated desert communities and campgrounds have their colonies; indeed, numbers in such places can be quite large (75 at Ocotillo Wells, I28, even many of these. House Sparrows are largely absent 26 April 2001, J. R. Barth). The Anza–Borrego Desert also above 4500 feet elevation, although there may be build- furnished our largest one-day estimate of House Sparrow ings that would attract them elsewhere. numbers in the breeding season, 200 in the Club Circle Nesting: House Sparrows most typically nest in a crevice area of Borrego Springs (G24) 15 April 2001 (L. and M. in buildings, filling the cavity with grass and trash. In Polinsky). The apparent gaps in a few squares with appre- southern California, the birds commonly use the gaps ciable urban development were likely due to atlas observ- under curved Spanish roof tiles, so much so that build- ers’ concentrating on natural habitats at the expense of ers now attempt to exclude House Sparrows—not always developed areas. -

Investigation Into the Causes of the Decline of Starlings and House Sparrows in Great Britain

BTO Research Report No 290 Investigation into the causes of the decline of Starlings and House Sparrows in Great Britain Edited by Humphrey Q. P. Crick, Robert A. Robinson, Graham F. Appleton, Nigel A. Clark & Angela D. Rickard A report to the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs by A consortium led by the British Trust for Ornithology Consortium Members: British Trust for Ornithology Central Science Laboratory Royal Society for the Protection of Birds/University of Oxford & WildWings Bird Management July 2002 © Copyright: Consortium Members British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk, IP24 2PU Registered Charity No. 216652 Editors' Note [added after report was produced] Starlings Sturnus vulgaris and House Sparrows Passer domesticus are amongst the most widespread and abundant bird species in the world. This is due, in large part, to the fact that both species are highly commensal with man and appear to benefit from the presence of towns and farms. For many years in Britain and elsewhere, both Starlings and House Sparrows have been considered as disease-carrying or agricultural pests and both species also gather in large urban roosts where fouling of pavements and buildings can be a significant problem. In the 1990s, it became clear that both species were undergoing rapid declines (greater than 50% over 25 years) in Britain, such that they had become candidate species for inclusion on the Red List of Species of Conservation Concern and as Priority Species under Britain’s Biodiversity Action Plan. The reasons for these declines in the wider countryside were unknown and there were indications that they were also declining in urban situations. -

International Studies on Sparrows

Intern. Stud. Sparrows 2007, 32: 5-14 ISSN 1734-624X FACULTY OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES, UNIVERSITY OF ZIELONA GÓRA INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR ECOLOGY WORKING GROUP ON GRANIVOROUS BIRDS – INTECOL ___________________________________________________________________ INTERNATIONAL STUDIES ON SPARROWS _________________________________________________________________________ Vol. 32 University of Zielona Góra Zielona Góra 2007 Edited by Working Group on Granivorous Birds – INTECOL Editor: Jan Pinowski, Prof. Dr. (CES PAS, PL) Co-editors: Leszek Jerzak, Dr. habil. (University of Zielona Góra, PL) Brendan Kavanagh, Associate Prof. Dr. (RCSI Medical University of Bahrain) Piotr Tryjanowski, Prof. Dr. (Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, PL) Address to Editor: Prof. Dr. Jan Pinowski, ul. Daniłowskiego 1/33, PL 01-833 Warszawa e-mail: [email protected] „International Studies on Sparrows” since 1967 Address: Faculty of Biological Sciences, University of Zielona Góra ul. prof. Z. Szafrana 1, PL 65-516 Zielona Góra e-mail: [email protected] (Funded by the Faculty of Biological Sciences, University of Zielona Góra) 2 Contents Jan PINOWSKI – History of the Working Group on Granivorous Birds Productivity Terrestrial Section of the International Biological Programme (later International Association for Ecology) .............................................................................................. 5 Jörg BÖHNER, Klaus WITT – Distribution, abundance and dynamics of the House Sparrow Passer domesticus in Berlin: a review .......................................15