The Persian Leopard Prowls Its Way to Survival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carnivores of Syria 229 Doi: 10.3897/Zookeys.31.170 RESEARCH ARTICLE Launched to Accelerate Biodiversity Research

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 31: 229–252 (2009) Carnivores of Syria 229 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.31.170 RESEARCH ARTICLE www.pensoftonline.net/zookeys Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Carnivores of Syria Marco Masseti Department of Evolutionistic Biology “Leo Pardi” of the University of Florence, Italy Corresponding author: Marco Masseti (marco.masseti@unifi .it) Academic editors: E. Neubert, Z. Amr | Received 14 April 2009 | Accepted 29 July 2009 | Published 28 December 2009 Citation: Masseti, M (2009) Carnivores of Syria. In: Neubert E, Amr Z, Taiti S, Gümüs B (Eds) Animal Biodiversity in the Middle East. Proceedings of the First Middle Eastern Biodiversity Congress, Aqaba, Jordan, 20–23 October 2008. ZooKeys 31: 229–252. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.31.170 Abstract Th e aim of this research is to outline the local occurrence and recent distribution of carnivores in Syria (Syrian Arab Republic) in order to off er a starting point for future studies. The species of large dimensions, such as the Asiatic lion, the Caspian tiger, the Asiatic cheetah, and the Syrian brown bear, became extinct in historical times, the last leopard being reputed to have been killed in 1963 on the Alauwit Mountains (Al Nusyriain Mountains). Th e checklist of the extant Syrian carnivores amounts to 15 species, which are essentially referable to 4 canids, 5 mustelids, 4 felids – the sand cat having been reported only recently for the fi rst time – one hyaenid, and one herpestid. Th e occurrence of the Blandford fox has yet to be con- fi rmed. Th is paper is almost entirely the result of a series of fi eld surveys carried out by the author mainly between 1989 and 1995, integrated by data from several subsequent reports and sightings by other authors. -

Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis for the Caspian Sea

TRANSBOUNDARY DIAGNOSTIC ANALYSIS FOR THE CASPIAN SEA Volume Two THE CASPIAN ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME BAKU, AZERBAIJAN September 2002 Caspian Environment Programme Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis Table of Contents Volume Two 1.0 THE CASPIAN SEA AND ITS SOCIAL, ECONOMIC AND LEGAL SETTINGS ..... 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 PHYSICAL AND BIOGEOCHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE CASPIAN SEA ...................... 3 1.3 SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND DEVELOPMENT SETTING .............................................................. 23 1.4 LEGAL AND REGULATORY SETTING .................................................................................. 39 2.0 MAJOR TRANSBOUNDARY PERCEIVED PROBLEMS AND ISSUES .................... 50 2.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 50 2.2 STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS ................................................................................................ 51 2.3 DECLINE IN CERTAIN COMMERCIAL FISH STOCKS, INCLUDING STURGEON: STRONGLY TRANSBOUNDARY. ............................................................................................................ 59 2.4 DEGRADATION OF COASTAL LANDSCAPES AND DAMAGE TO COASTAL HABITATS: STRONGLY TRANSBOUNDARY. ........................................................................................... 69 2.5 THREATS TO BIODIVERSITY: STRONGLY TRANSBOUNDARY. ............................................. -

Pre-Feasibility Study on the Possible Restoration of the Caspian Tiger in the Amu Darya Delta By

Pre-Feasibility Study on the Possible Restoration of the Caspian Tiger in the Amu Darya Delta by Hartmut Jungius, Yuri Chikin, Oleg Tsaruk, Olga Pereladova 2009 Contents Executive Summary I: Introduction 1. Study Methods 2. Basic Considerations for Restoration of Wildlife Populations II: Species Distribution, Habitat and Biology 1. Former Distribution 2. Decline 3. Tiger Habitats in Central Asia with Particular Reference to Amu Darya 3.1 Central Asia 3.2 Amu Darya Delta 4. Climate 5. Fauna with Particular Reverence to the Tiger 6. Human Use of the Amu Darya Delta 6.1 Dams and Polders 6.2 Agriculture 6.3 Hunting 6.4 Fisheries 6.5 Oil and Gas 6.6 Tourism 6.7 Protected Area and Nature Conservation 7. The Biology of the Caspian Tiger 7.1 Habitat Requirements 7.2 Behavior 7.3 Food 7.4 Home Range III: Discussion and Conclusions IV: Recommendations V: Acknowledgements VI: References VII: Annexes Annex 1: Survey Route and Sites Visited Annex 2: Former Distribution of the Tiger in Central Asia Annex 3: Priority Sites in the Amu Darya Delta for Habitat and Wildlife Restoration Annex 4: Lake System of the Amu Darya Delta Annex 5: Aral Sea Basin, Duststorm Annex 6: Photos Executive Summary: The Caspian tigers occurred in eastern Turkey, the southern Caucasus, in northern Iran, Iraq, and in isolated pocket throughout Central Asia until northwestern China. In Central Asia the tiger was found along floodplains of rivers and in tall grass and reed beds along rivers and lakes. This type of riparian forest is called “Tugai” and used to be widespread throughout the region. -

Turkey's First Wildlife Corridor Links Bear, Wolf

1/22/13 Turkey’s First Wildlife Corridor Links Bear, Wolf and Lynx Populations to the Caucasus Forests – News Watch News Watch » Top 25 Photographs from the Wilderness… Jan. 11, 2013 (17) News Watch » New Great Lakes Map Highlights Environmental… Jan. 10, 2013 (6) News Watch » PrevNext News Watch Home StarStruck Digital Diversity Explorers Journal Water Currents Pop Omnivore Ocean Views Weird & Wild Voice for Elephants Change Reaction Phenomena Turkey’s First Wildlife Corridor Links Bear, Wolf and Lynx Populations to the Caucasus Forests Posted by Çağan Şekercioğlu of University of Utah & KuzeyDoğa Society on February 13, 2012 (3) Like 169 84 7 More » Dr. Çağan Şekercioğlu is a National Geographic Emerging Explorer. A professor of conservation biology, ecology and ornithology at the University of Utah Department of Biology, he also directs the Turkish environmental organization KuzeyDoğa. newswatch.nationalgeographic.com/2012/02/13/turkeys-first-wildlife-corridor-links-bear-wolf-and-lynx-populations-to-the-caucasus-forests/ 5/13 1/22/13 Turkey’s First Wildlife Corridor Links Bear, Wolf and Lynx Populations to the Caucasus Forests – News Watch A gray wolf (Canis lupus) photographed by one of KuzeyDoğa‘s camera traps in Kars Turkey (Türkiye) is the only country covered almost entirely by three of the world’s 34 global biodiversity hotspots: the Caucasus, Irano-Anatolian,and the Mediterranean. At the nexus of Europe, the Middle East, Central Asia and Africa, Turkey’s location, mountains, and its encirclement by four seas (Black, Marmara, Aegean, and Mediterrenean) have resulted in spectacular biodiversity, making Turkey “the biodiversity superpower of Europe“. Of over 9000 native vascular plant species known from Turkey, one third are endemic. -

Tiger in Iran

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 10 | Autumn 2016 CatsCAT in Iran news 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, a component Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the International Union Co-chairs IUCN/SSC for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is published twice a year, and is Cat Specialist Group available to members and the Friends of the Cat Group. KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, Switzerland For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send <[email protected]> contributions and observations to [email protected]. Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews Cover Photo: From top left to bottom right: Caspian tiger (K. Rudloff) This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with support Asiatic lion (P. Meier) from the Wild Cat Club and Zoo Leipzig. Asiatic cheetah (ICS/DoE/CACP/ Panthera) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh caracal (M. Eslami Dehkordi) Layout: Christine Breitenmoser & Tabea Lanz Eurasian lynx (F. Heidari) Print: Stämpfli Publikationen AG, Bern, Switzerland Pallas’s cat (F. Esfandiari) Persian leopard (S. B. Mousavi) ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group Asiatic wildcat (S. B. Mousavi) sand cat (M. R. Besmeli) jungle cat (B. Farahanchi) The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

The Case of the Caspian Tiger

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2012 A postulate for tiger recovery: the case of the Caspian Tiger Carlos A. Driscoll University of Oxford I Chestin H Jungius Y Darman E Dinerstein See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, and the Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Driscoll, Carlos A.; Chestin, I; Jungius, H; Darman, Y; Dinerstein, E; Seidensticker, J; Sanderson, J; Christie, S; Luo, S J.; Shrestha, M; Zhuravlev, Y; Uphyrkina, O; Jhala, Y V.; Yadav, S P.; Pikunov, D G.; Yamaguchi, N; Wildt, D E.; Smith, J D.; Marker; Nyhus, Philip J.; Tilson, R; Macdonald, D W.; and O'Brien, S J., "A postulate for tiger recovery: the case of the Caspian Tiger" (2012). Faculty Scholarship. 5. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/faculty_scholarship/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. Authors Carlos A. Driscoll, I Chestin, H Jungius, Y Darman, E Dinerstein, J Seidensticker, J Sanderson, S Christie, S J. Luo, M Shrestha, Y Zhuravlev, O Uphyrkina, Y V. Jhala, S P. Yadav, D G. Pikunov, N Yamaguchi, D E. Wildt, J D. Smith, Marker, Philip J. Nyhus, R Tilson, D W. Macdonald, and S J. O'Brien This article is available at Digital Commons @ Colby: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/faculty_scholarship/5 JoTT OPINION 4(6): 2637–2643 A postulate for tiger recovery: the case of the Caspian Tiger C.A. -

Species at Risk Status and Distribution of the Leopard (Panthera Pardus) in Turkey and the Caucasus Mountains

Species at Risk Status and Distribution of the Leopard (Panthera pardus) in Turkey and the Caucasus Mountains Kirk Johnson Abstract For millennia large mammalian carnivores, including the Caspian tiger International Ecological Partnerships (Panthera tigris virgata), Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica), brown bear PSC 88 Box 2721 APO AE (Ursus arctos), gray wolf (Canis lupus), striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena), 09821-2700 Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) and three subspecies of leopard (Panthera pardus [email protected] tulliana, P.p. saxicolor and P.p. ciscaucasica) roamed mountains, plateaus and grasslands of Turkey, historically known as Asia Minor or Anatolia. Of the big cats, only the leopard and Eurasian lynx remain in increasingly isolated mountainous habitats. Evidence suggests a few leopards remain in Turkey's Black Sea mountain ranges and the inaccessible peaks of the Taurus Mountains in the south. Also, despite centuries of persecution, the leopard still exists in the Greater and Lesser Caucasus Ranges of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia, receiving some juvenile immigration from a larger population in northern Iran's Zagros Mountains. Leopard conservation throughout the Caucasus countries and Turkey will only succeed if viable populations of ungulate prey such as the Bezoar goat (Capra aegagrus), and wild boar (Sus scrofa) can be sustained in protected and unprotected habitats, and people in the region are educated about the importance of these species to the sustainability of the ecosystem. Vol. 20 No. 3 2003 Endangered Species UPDATE 107 Estatus y Distribución del Leopardo (Panthera pardus) en Turquía y las Montañas Caucásicas Resumen Durante miles de años varias especies de carnívoros poblaron las montañas, planicies y praderas de Turquía, región históricamente conocida como Asia Menor o Anatolia. -

Caspian Tiger Fact Sheet

Caspian Tiger Fact Sheet Common Name: Caspian Tiger Scientific Name: Panthera tigris tigris Wild Status: Extinct Habitat: Wetlands Country: Various countries in Central Asia and the Middle East Shelter: Trees Life Span: Unknown Size: 10ft long Details The story of the Caspian Tiger is a familiar one. Human expansion and hunting drove the number of Caspian Tigers down to dangerous levels, with some paying generously for their furs. Individual sightings became special occasions. The last observed Caspian Tiger was seen in the 70s, with the species being declared extinct in 2003. Like with many animals, efforts were made to protect the species before its extinction, which may have extended their lives for a few decades. A protected area called Trigovaya Balka was home to Caspian Tigers until 1958, when the last individual was seen. Cool Facts • Like all tigers, the Caspian Tiger was a carnivore who rarely, if ever, fed on plants • Their population seems to have been dispersed randomly, due to fragmentation by humans. • This species has been spotted in Turkey, Iraq, Iran, China, Russia, Georgia, and Kazakhstan. • Most likely hunted boars and deer, sometimes approaching civilization to eat cattle and dogs • Like many extinct species, a combination of hunting and loss of habitat doomed the Caspian Tiger • Like most big cats, their only predator was likely humans Taxonomic Breakdown Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Suborder: Feliformia Family: Felidae Subfamily: Pantherinae Genus: Panthera Species: P. tigris Subspecies: P. t. tigris Conservation & Helping Extinct, with some efforts to bring it back, much like the Quagga. Tigers in the Amur river, also home to the Amur Leopard, have been found to be close enough genetically to the Caspian Tiger to occupy the same niche. -

THE Official Magazine of the OCEANOGRAPHY SOCIETY

OceanThe OFFicial MagaZineog OF thE Oceanoraphygraphy Society CITATION Dybas, C.L. 2011. Ripple marks—The story behind the story.Oceanography 23(4):8–11, doi:10.5670/oceanog.2010.15. COPYRIGHT This article has been published inOceanography , Volume 23, Number 4, a quarterly journal of The Oceanography Society. Copyright 2010 by The Oceanography Society. All rights reserved. USAGE Permission is granted to copy this article for use in teaching and research. Republication, systematic reproduction, or collective redistribution of any portion of this article by photocopy machine, reposting, or other means is permitted only with the approval of The Oceanography Society. Send all correspondence to: [email protected] or The Oceanography Society, PO Box 1931, Rockville, MD 20849-1931, USA. doWnloaded From WWW.toS.orG/oceanography Ripple Marks The Story Behind the Story B Y CHERYL LYN DYBAS They Met on the Silk Road—Tigers of the Riparian Tugai, Coniferous Taiga Once Mingled on Fabled Highway I imagine a tiger. former river channel.” director of conservation at the Minnesota He’ll move through the forest and his days No tigers were glimpsed there after Zoo in Minneapolis, if it’s attempted in Leaving his traces on the mud banks 1958. Although still a matter of debate, the the right habitat. Of a river whose name he doesn’t know. legendary final wild Caspian tiger may have That habitat istugai . In his world there are no names or past been killed in February 1970, in Hakkari Stretching through Central Asia in long Or future, only the certainty of now. Province, Turkey. green strands, tugai was once widespread. -

Researchers Plan to Bring the Caspian Tiger Back

Researchers Plan To Bring The Caspian Tiger Back From The Dead http://www.iflscience.com/plants-and-animals/researchers-plan-to-bring-the-caspian-tiger-back-from-the-dead/ The Caspian tiger, Panthera tigris virgata, is a subspecies of tiger that went extinct back in the 1960s. These beasts, which can weigh more than 136 kilograms (300 pounds), were among the largest cats to have ever lived. However, a new study in the journal Biological Conservation suggests that they can be effectively resurrected, all thanks to another subspecies of tiger found in the mysterious and frigid eastern realms of Russia. An international team of researchers, funded in part by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), has an ambitious plan to capture a handful of these genetically similar tigers and reintroduce them back to Central Asia – but before we get into this, a little backstory is required. The Caspian tiger was effectively doomed the moment that Russia colonized Turkestan, a region that includes parts of Russia, Mongolia, China, Kazakhstan, Iraq, Afghanistan, and several other central Asian nations. Not only were their woodland habitats rapidly converted to cropland, but they were hunted by sportsman and military factions for fun and training purposes. Plenty of wild pigs – their prey – died out during the early 20th century too, due to hunting, natural disasters, and the spread of disease. Curiously, modern genetic analysis of another tiger subspecies, the Siberian (Amur) Tiger variant found in Russia, revealed the two subspecies had diverged from a common ancestor relatively recently. Importantly, the Siberian tiger is still alive, and although classified as “Endangered”, it can be found roaming the Sikhote Alin mountain region and the Primorye Province in the Russian Far East. -

Feasibility Study on the Possible Restoration of the Caspian Tiger in Central Asia By

Feasibility Study on the Possible Restoration of the Caspian Tiger in Central Asia by Hartmut Jungius 2010 Contents Executive Summary I: Introduction 1. Study Methods II: Species Distribution, Habitat and Biology 1. Former Distribution in Central Asia with Particular Reference to the Ily- Balkhash Basin 2. Decline of the Tiger in Central Asia with Particular Reference to the Ily- Balkhash Basin 3. Tiger Habitats in the Ily-Balkash Basin 4. Climate 5. Fauna with Particular Reverence to the Tiger 6. Human Use of the Ily-Balkash Basin 6.1 Hydrology and Water Management 6.2 Agriculture 6.3 Hunting and Fishing 6.4 Tourism 6.5 Nature Conservation and Protected Area 7. The Biology of the Tiger 7.1 Habitat Requirements III: Discussion IV: Conclusions V: Recommendations VI: Acknowledgements VII: References VIII: Annexes Cover Photo: Siberian Tiger in Sikhote Alin (WWF/Canon H. Jungius). Photos Ily Delta: WWF/Canon H. Jungius Executive Summary: The Caspian Tiger occurred in eastern Turkey, the southern Caucasus, in northern Iran, Iraq, and in isolated pockets throughout Central Asia until north-western China. In Central Asia the tiger was found along floodplains of rivers and in tall grass and reed beds along rivers and lakes. This type of riparian forest is called “Tugai” and used to be widespread throughout the region. The tiger became extinct in the region about 40 year ago. The main reason for its disappearance was habitat destruction and hunting (even extermination as vermin during reclamation of new lands in 19-th century) and the decline of its prey base. Stimulated by recent findings that the Amur- or Siberian Tiger is the closest relative of the Caspian Tiger, discussions started if the Amur Tiger could be an appropriate substitute for reintroduction into a save place in Central Asia. -

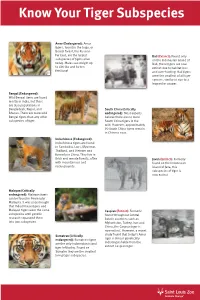

Extinct): Found Only Subspecies of Tigers Alive on the Indonesian Island of Today

Know Your Tiger Subspecies Amur (Endangered): Amur tigers, found in the taiga, or Boreal forest, the Russian Far East, are the largest Bali (Extinct): Found only subspecies of tigers alive on the Indonesian island of today. Males can weight up Bali, these tigers are now to 600 lbs and be ten extinct due to habitat loss feet long! and over-hunting. Bali tigers were the smallest of all tiger species, similar in size to a leopard or cougar. Bengal (Endangered): Wild Bengal tigers are found mostly in India, but there are also populations in Bangladesh, Nepal, and South China (Critically Bhutan. There are more wild endangered): Most experts Bengal tigers than any other believe there are no more subspecies of tiger. South China tigers in the wild. However, approximately 90 South China tigers remain in Chinese zoos. Indochinese (Endangered): Indochinese tigers are found in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam and formerly in China. They live in thick and remote forests, often Javan (Extinct): Formerly with mountainous and found on the Indonesian rocky grounds. island of Java, this subspecies of tiger is now extinct. Malayan (Critically endangered): Malayan tigers can be found in Peninsular Malaysia. It was once thought that Indochinese tigers and Malayan tigers were the same Caspian (Extinct): Formerly subspecies until genetic found throughout Central research separated them Asia in countries such as into two subspecies. Afghanistan, Turkey, Iran and China, the Caspian tiger is now extinct. However, a recent Sumatran (Critically study found that today’s Amur endangered): Sumatran tigers tiger is almost genetically are the only Indonesian island indistinguishable from the tiger left today.