Master's Thesis Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

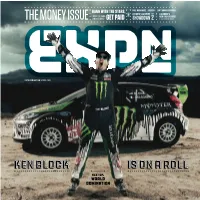

KEN BLOCK Is on a Roll Is on a Roll Ken Block

PAUL RODRIGUEZ / FRENDS / LYN-Z ADAMS HAWKINS HANG WITH THE STARS, PART lus OLYMPIC HALFPIPE A SLEDDER’S (TRAVIS PASTRANA, P NEW ENERGY DRINK THE MONEY ISSUE JAMES STEWART) GET PAID SHOWDOWN 2 IT’S A SHOCKER! PAGE 8 ESPN.COM/ACTION SPRING 2010 KENKEN BLOCKBLOCK IS ON A RROLLoll NEXT UP: WORLD DOMINATION SPRING 2010 X SPOT 14 THE FAST LIFE 30 PAY? CHECK. Ken Block revolutionized the sneaker Don’t have the board skills to pay the 6 MAJOR GRIND game. Is the DC Shoes exec-turned- bills? You can make an action living Clint Walker and Pat Duffy race car driver about to take over the anyway, like these four tradesmen. rally world, too? 8 ENERGIZE ME BY ALYSSA ROENIGK 34 3BR, 2BA, SHREDDABLE POOL Garth Kaufman Yes, foreclosed properties are bad for NOW ON ESPN.COM/ACTION 9 FLIP THE SCRIPT 20 MOVE AND SHAKE the neighborhood. But they’re rare gems SPRING GEAR GUIDE Brady Dollarhide Big air meets big business! These for resourceful BMXer Dean Dickinson. ’Tis the season for bikinis, boards and bikes. action stars have side hustles that BY CARMEN RENEE THOMPSON 10 FOR LOVE OR THE GAME Elena Hight, Greg Bretz and Louie Vito are about to blow. FMX GOES GLOBAL 36 ON THE FLY: DARIA WERBOWY Freestyle moto was born in the U.S., but riders now want to rule MAKE-OUT LIST 26 HIGHER LEARNING The supermodel shreds deep powder, the world. Harley Clifford and Freeskier Grete Eliassen hits the books hangs with Shaun White and mentors Lyn-Z Adams Hawkins BOBBY BROWN’S BIG BREAK as hard as she charges on the slopes. -

European Journal of American Studies, 14-4 | 2019 Spectacular Bodies: Los Angeles Beach Cultures and the Making of the “Califor

European journal of American studies 14-4 | 2019 Special Issue: Spectacle and Spectatorship in American Culture Spectacular Bodies: Los Angeles Beach Cultures and the Making of the “California Look” (1900s-1960s) Elsa Devienne Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/15480 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.15480 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Elsa Devienne, “Spectacular Bodies: Los Angeles Beach Cultures and the Making of the “California Look” (1900s-1960s)”, European journal of American studies [Online], 14-4 | 2019, Online since 23 December 2019, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/15480 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.15480 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License Spectacular Bodies: Los Angeles Beach Cultures and the Making of the “Califor... 1 Spectacular Bodies: Los Angeles Beach Cultures and the Making of the “California Look” (1900s-1960s) Elsa Devienne 1 In 1951, Life magazine ran a photo essay celebrating the vitality of West Coast youth. Among the many pictures of young Californians portrayed sailing, skiing, horse-riding, and surfing, one photograph stood out. Set in Santa Monica’s famous “Muscle Beach” playground, it pictured five bodybuilders wearing tight briefs and showing off their bulging biceps. Despite their obvious efforts to look good, the five men were mocked in the accompanying text for “carrying the body cult from the sublime to the absurd.” Clearly, the Life magazine journalists were unimpressed by such a display. As was Charles Flynn, a reader from Pawtucket, Rhode Island, who felt compelled to send a photograph, printed in the next issue’s Letters to the Editor, to “show.. -

Adidas' Bjorn Wiersma Talks Action Sports Selling

#82 JUNE / JULY 2016 €5 ADIDAS’ BJORN WIERSMA TALKS ACTION SPORTS SELLING TECHNICAL SKATE PRODUCTS EUROPEAN MARKET INTEL BRAND PROFILES, BUYER SCIENCE & MUCH MORE TREND REPORTS: BOARDSHORTS, CAMPING & OUTDOOR, SWIMWEAR, STREETWEAR, SKATE HARDWARE & PROTECTION 1 US Editor Harry Mitchell Thompson HELLO #82 [email protected] At the time of writing, Europe is finally protection and our Skateboard Editor, Dirk seeing some much needed signs of summer. Vogel looks at how the new technology skate Surf & French Editor Iker Aguirre April and May, on the whole, were wet brands are introducing into their decks, wheels [email protected] across the continent, spelling unseasonably and trucks gives retailers great sales arguments green countryside and poor spring sales for for selling high end products. We also have Senior Snowboard Contributor boardsports retail. However, now the sun our regular features; Corky from Stockholm’s shines bright and rumours are rife of El Niño’s Coyote Grind Lounge claims this issue’s Tom Wilson-North tail end heating both our oceans and air right Retailer Profile after their second place finish [email protected] the way through the summer. All is forgiven. at last year’s Vans Shop Riot series. Titus from Germany won the competition in 2015 and their Skate Editor Dirk Vogel Our business is entirely dependent on head of buying, PV Schulz gives us an insight [email protected] Mother Nature and with the Wanderlust trend into his buying tricks and tips. that’s sparked a heightened lust for travel in Millenials, spurred on by their need to document Our summer tradeshow edition is thoughtfully German Editor Anna Langer just how “at one” with nature they are, SOURCE put together to provide retailers with an [email protected] explores a new trend category in our Camping & extensive overview of SS17’s trends to assist Outdoor trend report. -

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Echo Publications 5-1-2007 Echo, Summer/Fall 2007 Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/echo Part of the Journalism Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Echo, Summer/Fall 2007" (2007). Echo. 23. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/echo/23 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Echo by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. '' ,fie..y fiutve.. ut -fr/e..tidly etiv/ro Mf!..ti--r uttid --rfie/re.. yood --ro --rfie../r cv1~--r0Me..r~ . .. · ECHO STAFF features editors STORAGE TODAY? I I mare ovies I' katie a. VOSS Guaranteed Availability.... departments editors amie langus bethel swift intensecity editors mary kroeck meagan pierce staff writers brianne coulom mary kroeck matt lambert amie langus rebecca michuda frances moffett mare ovies meagan pierce joel podbereski geneisha ryland bethel swift katie a. VOSS LetAve Lt wLtVl photo/illustration editor stacy smith photographers STORAGE TODAY® jessica bloom kristen hanson ryan jacobsen mary kroeck niki miller sarah nader hans seaberg stacy smith ryan thompson katie a. VOSS Illustrators ashley bedore alana crisci hans seaberg andrew walensa ECHO SUMMER I FALL 2007 www.echomagonline.com special thanks to University Village best western hotel 500 W. Cermak Rd. Echo magazine is published twice daniel grajdura Chicago, IL 60616 a year by the Columbia College ADMINISTRATION 312-492-8001 Journalism Department. -

Etnies Album Download Free Etnies Album Download Free

etnies album download free Etnies album download free. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67da3abdce05c41a • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Etnies album download free. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67da3abdadc384d4 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. -

”Shoes”: a Componential Analysis of Meaning

Vol. 15 No.1 – April 2015 A Look at the World through a Word ”Shoes”: A Componential Analysis of Meaning Miftahush Shalihah [email protected]. English Language Studies, Sanata Dharma University Abstract Meanings are related to language functions. To comprehend how the meanings of a word are various, conducting componential analysis is necessary to do. A word can share similar features to their synonymous words. To reach the previous goal, componential analysis enables us to find out how words are used in their contexts and what features those words are made up. “Shoes” is a word which has many synonyms as this kind of outfit has developed in terms of its shape, which is obviously seen. From the observation done in this research, there are 26 kinds of shoes with 36 distinctive features. The types of shoes found are boots, brogues, cleats, clogs, espadrilles, flip-flops, galoshes, heels, kamiks, loafers, Mary Janes, moccasins, mules, oxfords, pumps, rollerblades, sandals, skates, slides, sling-backs, slippers, sneakers, swim fins, valenki, waders and wedge. The distinctive features of the word “shoes” are based on the heels, heels shape, gender, the types of the toes, the occasions to wear the footwear, the place to wear the footwear, the material, the accessories of the footwear, the model of the back of the shoes and the cut of the shoes. Keywords: shoes, meanings, features Introduction analyzed and described through its semantics components which help to define differential There are many different ways to deal lexical relations, grammatical and syntactic with the problem of meaning. It is because processes. -

Surfing, Gender and Politics: Identity and Society in the History of South African Surfing Culture in the Twentieth-Century

Surfing, gender and politics: Identity and society in the history of South African surfing culture in the twentieth-century. by Glen Thompson Dissertation presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Albert M. Grundlingh Co-supervisor: Prof. Sandra S. Swart Marc 2015 0 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the author thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 8 October 2014 Copyright © 2015 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved 1 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This study is a socio-cultural history of the sport of surfing from 1959 to the 2000s in South Africa. It critically engages with the “South African Surfing History Archive”, collected in the course of research, by focusing on two inter-related themes in contributing to a critical sports historiography in southern Africa. The first is how surfing in South Africa has come to be considered a white, male sport. The second is whether surfing is political. In addressing these topics the study considers the double whiteness of the Californian influences that shaped local surfing culture at “whites only” beaches during apartheid. The racialised nature of the sport can be found in the emergence of an amateur national surfing association in the mid-1960s and consolidated during the professionalisation of the sport in the mid-1970s. -

Skate Bearings

+91-8048736845 LazerXTech https://www.lazerxtech.com/ We are a leading business entity, engaged in Manufacturer, Exporter, Importer and Traders a range of Quad Skates Packages, Skate Accessories, Roller Skate and Equipment, Inline Skate Accessories and Equipment, etc. to our valued clients. About Us Established in the year 2008, we, LAZER X TECH, are engaged in the sphere of Manufacturer, Exporter, Importer and Traders a range of Skates, Associated Accessories and Related Products. Our range includes Quad Skates Packages, Inline Skates Wheel, Skate Boot, Inline Skate Frames, Skate Bearings, Skin Suits, Skate Bags, Skate Accessories, Ionic Flux Black Bearing Oil, Collagen Peptide, Hydration Product, Inline Hockey Sticks, Cycling Helmet, Allen Key With Bearing Puller, Inline Skates Shoes and Plastic Skateboards. The entire range is manufactured by using quality raw material under the supervision of expert quality controllers, who ensure that no defected product goes out of the manufacturing unit. Being a quality conscious organization, we manufacture products in accordance with various international quality parameters. We use sophisticated machines so that we can meet the strict delivery schedules within the stipulated period. Further, to suit the varied requirements of the clients, we can also offer the customized range of our Skates, Associated Accessories and Related Products. Under the able guidance of our owner, Mr. Rahul Ramesh Rane, who has more than 26 years of experience of this industry, we have achieved new heights of success. -

X GAMES FACTS & FEATS 1995 the Inaugural Extreme Games Took

X GAMES FACTS & FEATS 1995 The inaugural Extreme Games took place in June in Providence, R.I. with the following competitions: Bungee Jumping Eco Challenge In-Line Skating Skateboard Sky Surfing Sport Climbing Street Luge Biking Watersports 1997 Extreme Games changed its name to X Games and moved to the west coast for the first time – hosted by San Diego, Calif. 1999 The X Games moved north to San Francisco, Calif. After attempting the trick for 10 years, Tony Hawk landed the first-ever 900 in Skateboard Best Trick. Moto X made its debut in 1999 and phenom Travis Pastrana was awarded a near-perfect score of 99.0 in Moto X Freestyle. 2000 Moto X Step Up made its first appearance. Dave Mirra became the first BMX athlete to land a double backflip at the X Games. 2001 X Games Seven headed back east to Philadelphia, Penn., where the event hit a major milestone – a first-time indoor venue at the First Union Center. This was the first time X Games took place inside and outside an arena. Moto X Best Trick made its debut. 2002 Mike Metzger made X Games and Moto X history with his back-to-back backflips. Mat Hoffman landed the first no-handed 900 in Vert. 2003 X Games made its third move, this time back to California and landed in Los Angeles with an unprecedented contract lasting through 2009. Becoming the youngest ever X Games gold medalist, Ryan Sheckler landed all of his tricks and won Skateboard Park at just 13 years old. -

X GAMES FACTS & FEATS 1995 the Inaugural Extreme Games Took

X GAMES FACTS & FEATS 1995 The inaugural Extreme Games took place in June in Providence, R.I. with the following competitions: • Bungee Jumping • Eco Challenge • In-Line Skating • Skateboard • Sky Surfing • Sport Climbing • Street Luge • Biking • Watersports 1997 Extreme Games changed its name to X Games and moved to the west coast for the first time – hosted by San Diego, Calif. 1999 The X Games moved north to San Francisco, Calif. After attempting the trick for 10 years, Tony Hawk landed the first-ever 900 in Skateboard Best Trick. Moto X made its debut in 1999 and phenom Travis Pastrana was awarded a near-perfect score of 99.0 in Moto X Freestyle. 2000 Moto X Step Up made its first appearance. Dave Mirra became the first BMX athlete to land a double backflip at the X Games. 2001 X Games Seven headed back east to Philadelphia, Penn., where the event hit a major milestone – a first-time indoor venue at the First Union Center. This was the first time X Games took place inside and outside an arena. Moto X Best Trick made its debut. 2002 Mike Metzger made X Games and Moto X history with his back-to-back backflips. Mat Hoffman landed the first no- handed 900 in Vert. 2003 X Games made its third move, this time back to California and landed in Los Angeles with an unprecedented contract lasting through 2009. Becoming the youngest ever X Games gold medalist, Ryan Sheckler landed all of his tricks and won Skateboard Park at just 13 years old. -

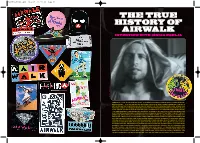

The True History of Airwalk Interview with Sinisa Egelja T R U T S N a D

ISSUE10-FINAL.qxd 18/6/07 11:55 AM Page 73 THE TRUE HISTORY OF AIRWALK INTERVIEW WITH SINISA EGELJA T R U T S N A D : : O T O H P serendipity is one of the loveliest words. accidental discoveries, random emails, chance meetings, happenstances... so it was earlier this year when i was struck with a rather unexpected dose which left me feeling that some things in life are just meant to be. the timing was impeccable. airwalk had randomly come up in conversation several times with independent people when i was introduced to a local vintage collector in melbourne who had a connection to a former employee. within hours, i had been referred to the one person in the world qualified to tell the story of this once mighty and most influential skate brand. however, for various reasons, he wasn’t that keen to revisit the past. after some gentle persuasion and even more luck, what started as a wild idea quickly turned into reality and a mad dash to so-cal, where i spent a few intense days talking shop with sinisa egelja, the first and virtually last employee of the original airwalk company. during his 16 years with the firm, ‘sin’ held various positions from skate team manager to head designer. from its origins as a start-up skate shoe company in 1985, we talked about how the brand evolved into a $200+ million company sponsoring surfers, bmx riders, base jumpers, boogie boarders and making a myriad of casual shoes, snow boots and dodgy brown loafers. -

Jan Holzers, Rvca European Brand Manager Local Skate Park Article Regional Market Intelligence Brand Profiles, Buyer Science & More

#87 JUNE / JULY 2017 €5 JAN HOLZERS, RVCA EUROPEAN BRAND MANAGER LOCAL SKATE PARK ARTICLE REGIONAL MARKET INTELLIGENCE BRAND PROFILES, BUYER SCIENCE & MORE RETAIL BUYER’S GUIDES: BOARDSHORTS, SWIMWEAR, SKATE FOOTWEAR, SKATE HARDGOODS, SKATE HELMETS & PROTECTION, THE GREAT OUTDOORS, HANGING SHOES ©2017 Vans, Inc. Vans, ©2017 Vans_Source87_Kwalks.indd All Pages 02/06/2017 09:41 US Editor Harry Mitchell Thompson [email protected] HELLO #87 Skate Editor Dirk Vogel Eco considerations were once considered a Show introducing a lifestyle crossover [email protected] luxury, however, with the rise of consumer section and in the States, SIA & Outdoor awareness and corporate social responsibility Retailer merging. Senior Snowboard Contributor the topic is shifting more and more into Tom Wilson-North focus. Accordingly, as the savvy consumer [email protected] strives to detangle themselves from the ties Issue 87 provides boardsports retail buyers of a disposable culture, they now require with all they need to know for walking the Senior Surf Contributor David Bianic fewer products, but made to a higher halls of this summer’s trade show season. It’s standard. Before, for example, a brand may with this in mind that we’re rebranding our [email protected] have intended for its jacket to be worn purely trend articles; goodbye Trend Reports, hello on the mountain, but now it’s expected to Retail Buyer’s Guides. As we battle through German Editor Anna Langer work in the snowy mountains, on a rainy information overload, it’s more important now [email protected] commute or for going fishing in. than ever before for retailers to trust their SOURCEs of information.