The Enumerated Powers of States'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Stephen Du Ponceau Collection 1781-1844 Mss.B.D92p

Peter Stephen Du Ponceau Collection 1781-1844 Mss.B.D92p American Philosophical Society 2004 105 South Fifth Street Philadelphia, PA, 19106 215-440-3400 [email protected] Peter Stephen DuPonceau Collection 1781-1844 Mss.B.D92p Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Background note ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope & content ..........................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................7 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Indexing Terms ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Other Descriptive Information ..................................................................................................................10 Collection Inventory ..................................................................................................................................12 Peter Stephen Du Ponceau Collection................................................................................................. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

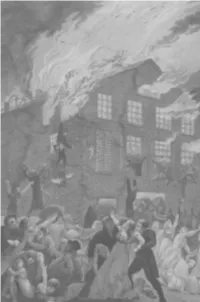

The Baltimore Riots of 1812 and the Breakdown of the Anglo-American Mob Tradition Author(S): Paul A

Peter N. Stearns The Baltimore Riots of 1812 and the Breakdown of the Anglo-American Mob Tradition Author(s): Paul A. Gilje Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of Social History, Vol. 13, No. 4 (Summer, 1980), pp. 547-564 Published by: Peter N. Stearns Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3787432 . Accessed: 02/11/2011 21:31 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Peter N. Stearns is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Social History. http://www.jstor.org THEBALTIMORE RIOTS OF 1812AND THE BREAKDOWNOF THE ANGLO-AMERICAN MOB TRADITION The nature of rioting-what riotersdid-was undergoinga transformationin the half century after the American Revolution. A close examination of the extensive rioting in Baltimoreduring the summer of 1812 suggests what those changes were. Telescopedinto a month and a half of riotingwas a rangeof activity revealing the breakdownof the Anglo-Americanmob tradition.l This tradition allowed for a certainamount of limited populardisorder. The tumultuouscrowd was viewed as a "quasi-legitimate"or "extra-institutionals'part -

The Approaching Death of the Collective Right Theory of the Second Amendment

Duquesne Law Review Volume 39 Number 1 Article 5 2000 The Approaching Death of the Collective Right Theory of the Second Amendment Roger I. Roots Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Roger I. Roots, The Approaching Death of the Collective Right Theory of the Second Amendment, 39 Duq. L. Rev. 71 (2000). Available at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr/vol39/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Duquesne Law Review by an authorized editor of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. The Approaching Death of the Collective Right Theory of the Second Amendment Roger L Roots* INTRODUCTION The Second Amendment reads: "A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed."' To most Americans, this language guarantees an individual right to keep and bear arms,2 in accordance with what is generally accepted as the plain language of the Amendment. 3 However, a rival interpretation of this language - the "collective right" theory of the Second Amendment,4 - has gained numerous converts in the federal judiciary' and the organized legal profession. 6 The collective right, * The author, Roger Isaac Roots, J.D., graduated from Roger Williams University School of Law in 1999 and Montana State University-Billings (B.S., Sociology) in 1995. He is the founder of the Prison Crisis Project, a not-for-profit prison and criminal justice law and policy think tank based in Providence, Rhode Island. -

Guide to the War of 1812 Sources

Source Guide to the War of 1812 Table of Contents I. Military Journals, Letters and Personal Accounts 2 Service Records 5 Maritime 6 Histories 10 II. Civilian Personal and Family Papers 12 Political Affairs 14 Business Papers 15 Histories 16 III. Other Broadsides 17 Maps 18 Newspapers 18 Periodicals 19 Photos and Illustrations 19 Genealogy 21 Histories of the War of 1812 23 Maryland in the War of 1812 25 This document serves as a guide to the Maryland Center for History and Culture’s library items and archival collections related to the War of 1812. It includes manuscript collections (MS), vertical files (VF), published works, maps, prints, and photographs that may support research on the military, political, civilian, social, and economic dimensions of the war, including the United States’ relations with France and Great Britain in the decade preceding the conflict. The bulk of the manuscript material relates to military operations in the Chesapeake Bay region, Maryland politics, Baltimore- based privateers, and the impact of economic sanctions and the British blockade of the Bay (1813-1814) on Maryland merchants. Many manuscript collections, however, may support research on other theaters of the war and include correspondence between Marylanders and military and political leaders from other regions. Although this inventory includes the most significant manuscript collections and published works related to the War of 1812, it is not comprehensive. Library and archival staff are continually identifying relevant sources in MCHC’s holdings and acquiring new sources that will be added to this inventory. Accordingly, researchers should use this guide as a starting point in their research and a supplement to thorough searches in MCHC’s online library catalog. -

Maryland Historical Magazine Patricia Dockman Anderson, Editor Matthew Hetrick, Associate Editor Christopher T

Winter 2014 MARYLAND Ma Keeping the Faith: The Catholic Context and Content of ry la Justus Engelhardt Kühn’s Portrait of Eleanor Darnall, ca. 1710 nd Historical Magazine by Elisabeth L. Roark Hi st or James Madison, the War of 1812, and the Paradox of a ic al Republican Presidency Ma by Jeff Broadwater gazine Garitee v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore: A Gilded Age Debate on the Role and Limits of Local Government by James Risk and Kevin Attridge Research Notes & Maryland Miscellany Old Defenders: The Intermediate Men, by James H. Neill and Oleg Panczenko Index to Volume 109 Vo l. 109, No . 4, Wi nt er 2014 The Journal of the Maryland Historical Society Friends of the Press of the Maryland Historical Society The Maryland Historical Society continues its commitment to publish the finest new work in Maryland history. Next year, 2015, marks ten years since the Publications Committee, with the advice and support of the development staff, launched the Friends of the Press, an effort dedicated to raising money to be used solely for bringing new titles into print. The society is particularly grateful to H. Thomas Howell, past committee chair, for his unwavering support of our work and for his exemplary generosity. The committee is pleased to announce two new titles funded through the Friends of the Press. Rebecca Seib and Helen C. Rountree’s forthcoming Indians of Southern Maryland, offers a highly readable account of the culture and history of Maryland’s native people, from prehistory to the early twenty-first century. The authors, both cultural anthropologists with training in history, have written an objective, reliable source for the general public, modern Maryland Indians, schoolteachers, and scholars. -

Jeffersons Rivals: the Shifting Character of the Federalists 23

jeffersons rivals: the shifting character of the federalists roberf mccolley Our first national political association, after the revolutionary patriots, was the Federalist Party, which controlled the Federal government for twelve years, and then dwindled rapidly away. Within its brief career this Federalist Party managed to go through three quite distinct phases, each of which revealed a different composition of members and of principles. While these are visible enough in the detailed histories of the early na tional period, they have not been clearly marked in our textbooks. An appreciation of the distinctness of each phase should reduce some of the confusion about what the party stood for in the 1790's, where Jeffersonians have succeeded in attaching to it the reactionary social philosophy of Hamilton. Furthermore, an identification of the leading traits of Feder alism in each of its three phases will clarify the corresponding traits in the opposition to Federalism. i. federalism as nationalism, 1785-1789 The dating of this phase is arbitrary, but defensible. Programs for strengthening the Articles of Confederation were a favorite subject of political men before Yorktown. In 1785 a national movement began to form. Several delegates met in that year at Mount Vernon to negotiate commercial and territorial conflicts between Virginia and Maryland. In formally but seriously they also discussed the problem of strengthening the national government. These men joined with nationally minded lead ers from other states to bring on the concerted movement for a new Constitution.1 The interesting questions raised by Charles Beard about the motives of these Federalists have partly obscured their leading concerns, and the scholarship of Merrill Jensen has perhaps clarified the matter less than it should have. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1942, Volume 37, Issue No. 3

G ^ MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE VOL. XXXVII SEPTEMBER, 1942 No. } BARBARA FRIETSCHIE By DOROTHY MACKAY QUYNN and WILLIAM ROGERS QUYNN In October, 1863, the Atlantic Monthly published Whittier's ballad, "' Barbara Frietchie." Almost immediately a controversy arose about the truth of the poet's version of the story. As the years passed, the controversy became more involved until every period and phase of the heroine's life were included. This paper attempts to separate fact from fiction, and to study the growth of the legend concerning the life of Mrs. John Casper Frietschie, nee Barbara Hauer, known to the world as Barbara Fritchie. I. THE HEROINE AND HER FAMILY On September 30, 1754, the ship Neptune arrived in Phila- delphia with its cargo of " 400 souls," among them Johann Niklaus Hauer. The immigrants, who came from the " Palatinate, Darmstad and Zweybrecht" 1 went to the Court House, where they took the oath of allegiance to the British Crown, Hauer being among those sufficiently literate to sign his name, instead of making his mark.2 Niklaus Hauer and his wife, Catherine, came from the Pala- tinate.3 The only source for his birthplace is the family Bible, in which it is noted that he was born on August 6, 1733, in " Germany in Nassau-Saarbriicken, Dildendorf." 4 This probably 1 Hesse-Darmstadt, and Zweibriicken in the Rhenish Palatinate. 2 Ralph Beaver Strassburger, Pennsylvania German Pioneers (Morristown, Penna.), I (1934), 620, 622, 625; Pennsylvania Colonial Records, IV (Harrisburg, 1851), 306-7; see Appendix I. 8 T. J. C, Williams and Folger McKinsey, History of Frederick County, Maryland (Hagerstown, Md., 1910), II, 1047. -

Bk Adbl 016864.Pdf

InternalEnemy_7pp.indd 4 7/3/13 12:40 PM T C R, CUMBERLAND LANCASTER BEDFORD YORK Su CHESTER sq PENNSYLVANIA u e h GLOUCESTER a n n HARFORD a CECIL Delaware R. R SALEM FREDERICK . Havre de Grace Frenchtown NEW BERKELEY MARYLAND NEW JERSEY HAMPSHIRE Frederick BALTIMORE CASTLE CUMBERLAND Baltimore Georgetown KENT FREDERICK Chestertown D ANNE ARUNDEL e l Winchester KENT a Poto Kent QUEEN w LOUDOUN ma Island ANNES a c R r . e B Annapolis a y Washington, D.C. CAROLINE TALBOT DUNMORE FAIRFAX PRINCE GEORGE'S FAUQUIER Alexandria DELAWARE PRINCE WILLIAM P a t u CALVERT VIRGINIA x e SUSSEX CHARLES n Benedict t CULPEPER R STAFFORD . C DORCHESTER Rappahanno h ck e R. s Chaptico a SOMERSET p KING Fredericksburg ST. e GEORGE MARY'S CO. a T k ORANGE SPOTSYLVANIA e WORCESTER M N a WESTMORELAND B N tt a a p Nomini Ferry o y O n i Charlottesville LOUISA Kinsale CAROLINE R M . RICHMOND Tappahannock E NORTHUMBERLAND R ALBEMARLE D ESSEX P O amu LANCASTER E nk Tangier ACCOMACK e H y R KING AND Island I HANOVER . S QUEEN GOOCHLAND KING Chesconessex Cr. P WILLIAM BUCKINGHAM James River Corotoman NPungoteague Creek R MIDDLESEX CUMBERLAND York R. Gwynn E E R. E T tox Richmond HENRICO NEW KENT Island at S m MATHEWS H o H p A p JAMES GLOUCESTER A CHESTERFIELD CHARLES CITY E NORTHAMPTON CO. T T CITY Williamsburg New Point PRINCE AMELIA PRINCE GEORGE Yorktown Comfort EDWARD Petersburg YORK NEWPORT DINWIDDIE SURRY NEWS HAMPTON Hampton LUNENBURG ISLE OF SUSSEX WIGHT Norfolk Lynnhaven Bay PRINCESS BRUNSWICK ANNE CO. -

Jonathan D. Meredith Papers

Jonathan D. Meredith Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Prepared by Theresa Salazar Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2012 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2012 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms012148 Collection Summary Title: Jonathan D. Meredith Papers Span Dates: 1795-1859 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1810-1859) ID No.: MSS32664 Creator: Meredith, Jonathan, 1783-1872 Extent: 9,000 items ; 15 containers plus 1 oversize ; 6 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Lawyer, army officer, and businessman of Baltimore, Md. Family and general correspondence, legal files, financial papers, and other material relating chiefly to Meredith's associations with the Savings Bank of Baltimore and the Bank of the United States; the War of 1812; impeachment proceedings against James Hawkins Peck; shipping and trade with Europe and South America; and settlement of the estates of Charles Carroll and Robert Oliver. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Aspinwall, William Henry, 1807-1875--Correspondence. Calderón de la Barca, Ángel--Correspondence. Carroll, Charles, 1737-1832--Estate. Cogswell, Joseph Green, 1786-1871--Correspondence. Duane, William J. (William John), 1780-1865--Correspondence. Gilmor, Robert, 1748-1822--Correspondence. Graham, John, 1774-1820--Correspondence. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1911, Volume 6, Issue No. 2

/V\5A.SC 5^1- i^^ MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE Voi,. VI. JUNE, 1911. No. 2. THE MARYLAND GUARD BATTALION, 1860-61.1 ISAAC F. NICHOLSON. (Bead before the Society April 10, 1911.) After an interval of fifty years, it is permitted the writer to avail of the pen to present to a new generation a modest record of a military organization of most brilliant promise— but whose career was brought to a sudden close after a life of but fifteen months. The years 1858 and 1859 were years of very grave import in the history of our city. Local political conditions had become almost unendurable, the oitizens were intensely incensed and outraged, and were one to ask for a reason for the formation of an additional military organization in those days, a simple reference to the prevailing conditions would be ample reply. For several years previous the City had been ruled by the American or Know Nothing Party who dominated it by violence through the medium of a partisan police and disorderly political clubs. No man of opposing politics, however respectable, ever undertook to cast his vote without danger to his life. 'The corporate name of this organization was "The Maryland Guard" of Baltimore City. Its motto, " Decus et Prsesidium." 117 118 MAEYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZIlfE. The situation was intolerable, and the State at large having gone Democratic, some of our best citizens turned to the Legis- lature for relief and drafted and had passed an Election Law which provided for fair elections, and a Police Law, which took the control of that department from the City and placed it in the hands of the State. -

The Slavery and the Constitutional Convention: Historical Perspectives

THE SLAVERY AND THE CONSTITUTIONAL end slavery at the Convention. Neo-Garrisonians also depict the CONVENTION: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES southern slave owning delegates as staunchly proslavery, unified in defending the institution, and expert bargainers. Paul Finkelman is Ryan Ervin perhaps the strongest critic of the founders. Depicting the southern delegates as a slave lobbying group, he writes “Rarely in American political history have the advocates of a special interest been so From September 17, 1787 to the present day, the United States successful. Never has the cost of placating a special interest been so Constitution has been the subject of much debate. Its vague language high.” When Finkelman asks whether the framers could have done and ambiguous wording have created disputes for generations about more to slow slavery’s growth and weaken its permanence on the the true meaning of particular clauses or the original intent of the American landscape, he says, “surely yes.” In fact, the delegates’ lack Framers. In its essence, the Constitution is a framework, an outline, of conviction in doing anything substantial about slavery “is part of for government, leaving future generations to add color and depth to a the tragedy of American history.” 1 broad, somewhat undefined blueprint. James Madison’s detailed notes Neo-Garrisonian criticism has not only focused on the three on the Convention have partially illuminated the struggle going on specific clauses which historians have generally agreed mention some behind the closed doors of Independence Hall, but they have also aspect of slavery; they have also cited any clause which tends to raised still more questions.