Is Dna Analysis the Key to Freeing the Wrongfully Convicted?*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paroles D'avocats N°42

Paroles d’ av ocats LE MAGAZINE DU CONSEIL NATIONAL DES BARREAUX N° 42 - SEPTEMBRE - OCTOBRE - NOVEMBRE 2012 RP VA un OUTIL INDISPENSABLE POUR LES AVOCATS Entretien avec Hommage à Assemblée Générale Pierre Rivière-Sacaze, Xavier Cirade Extraordinaire Président de l’ AnAAfA L A R D © Christian Charrière-Bournazel, Président du Conseil national des barreaux I L’AVOCAT GARANT DU DROIT ET GARDIEN DES LIBERT ÉS Chères consœurs, R Chers confrères, Votre magazine a fait peau neuve. Ce premier numéro est essentiellement consacré au RPVA. Vous verrez à quel point le barreau français s’est mobilisé pour le rendre plus accessible et plus efficace. Le 5 octobre aura lieu l’Assemblée Générale Extraordinaire du Conseil national des barreaux. Vous avez pu consulter le programme sur le site du CnB. Il est O imprimé dans les pages qui suivent. Vous serez attentifs aux personnalités du monde du droit, de l’économie, de la politique et de la presse qui nous feront l’honneur d’être présentes. Pour être toujours plus utiles et, par conséquent, plus heureux, nous avons besoin non seulement de nous retrouver entre nous, mais aussi d’échanger avec nos contemporains. T Attentifs à leurs besoins de droit, nous devons les écouter pour leur proposer ensuite l’assistance qu’ils souhaitent. À nous de nous appliquer en même temps à parfaire nos connaissances dans nos domaines d’exercice et à les élargir à des secteurs où nous sommes attendus, I faute de les avoir investis suffisamment. Enfin, nous aurons l’occasion de dire à ceux qui sont en charge des intérêts publics ce que nous attendons du gouvernement et du parlement pour renforcer 2 l’institution judiciaire, favoriser l’accès au droit, faciliter l’épanouissement de la 4 A P profession et veiller au respect des libertés et des droits de la personne humaine. -

The Innocence Revolution and Proposals to Modify the American Criminal Trial

Texas A&M Law Review Volume 3 Issue 2 2015 Reinventing the Trial: The Innocence Revolution and Proposals to Modify the American Criminal Trial Marvin Zalman Ralph Grunewald Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Marvin Zalman & Ralph Grunewald, Reinventing the Trial: The Innocence Revolution and Proposals to Modify the American Criminal Trial, 3 Tex. A&M L. Rev. 189 (2015). Available at: https://doi.org/10.37419/LR.V3.I2.2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Texas A&M Law Review by an authorized editor of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REINVENTING THE TRIAL: THE INNOCENCE REVOLUTION AND PROPOSALS TO MODIFY THE AMERICAN CRIMINAL TRIAL* By: Marvin Zalman** and Ralph Grunewald*** ABSTRACT Law review articles by D. Michael Risinger, Tim Bakken, Keith Findley, Samuel Gross, and Christopher Slobogin have proposed modifications to pre- trial and trial procedures designed to reduce wrongful convictions. Some fit within the adversary model and others have “inquisitorial” features. We com- pare and evaluate the recommendations from the perspectives of lawyer-schol- ars trained in the United States and Germany. We examine the proposals for their novelty, feasibility, complexity, likely impact, and possible negative or positive side effects. This Article describes, compares, and critically analyzes the articles; suggests additional truth-enhancing procedural reforms; and pro- vides a platform for further analysis. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. -

LA DEUXIÈME PORTE Dossiers

LA DEUXIÈME PORTE Dossiers Ouvrages déjà parus Dassault, Douglas, Boeing et les autres par Bernard Marck. Le Défi soviétique par Claude Durand-Berger. Une enquête de police sur « le Canard enchaîné » par Christian Plume et Xavier Pasquini. La Guerre des Truands par Claude Picant. Complots en France par Jean Renaud-Groison. L'Affaire de Broglie par Jacques Bacelon. Le Réseau Curiel ou la subversion humanitaire par Roland Gaucher. Elysée, sens interdit par Jean Renaud-Groison. Le 23 mars 1979, une provocation politique par Claude Picant. Nous avons tué Mountbatten, l'IRA parle par Roger Faligot. L'Argent nazi à la conquête de la presse française par Pierre-Marie $^àç_è_ç=)àçèyu%!mµùmù*lmù**ùmùµ*ùmµ$*^pmù*$*ù^pomù^$**ùm,k;!m:lm%µù^$*µ$ù§$^ùm:ù*ù*!ù*µ%mù!*µùmù*%mù**$ù^*µ%*ùmpùµµ%§m:µùù$*ùµ%mù**µ*ù*Dioudonnat. Dictionnaire maçonnique par Jean-André Faucher. Le Mythe de l'Hexagone par Olier Mordrel. © Éditions Jean Picollec, 1981. ISBN n° 2-86477-037-7 LA DEUXIÈME PORTE Editions Jean Picollec 47, rue Auguste Lançon - 75013 Paris Tél. 589-73-04 Enquête à Marseille de Dominique Gonod. Lorsque, le 25 mai 1981, les avocats de Philippe Maurice se retrouvent dans la cour de l'Elysée pour être reçus par François Mitterrand afin de plaider une dernière fois en faveur de la grâce du jeune criminel, ils ont une attitude qui choque presque les gardes républi- cains et les huissiers. Jean-Louis Pelletier et Philippe Lemaire se sont arrêtés face à face, à deux mètres de distance, ils ont regardé leurs pieds et ils ont éclaté de rire. -

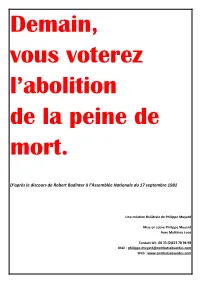

D'après Le Discours De Robert Badinter À L'assemblée Nationale

Demain, vous voterez l’abolition de la peine de mort. D’après le discours de Robert Badinter à l’Assemblée Nationale du 17 septembre 1981 Une création théâtrale de Philippe Muyard Mise en scène Philippe Muyard Avec Matthieu Loos Contact tél : 00 33 (0)623 78 94 98 Mail : [email protected] Web : www.combatsabsurdes.com L’auteur. Robert Badinter est un avocat et homme politique français né en 1928. Il exerça sa profession d’avocat de 1954 à 1981, au cours de laquelle il plaidera notamment comme avocat de la défense dans de nombreuses affaires criminelles qui portaient en elles, l’enjeu de la peine de mort pour les accusés. S’il ne réussit pas à éviter la peine capitale à Roger Bontems, il parviendra à soustraire Patrick Henry au même sort. Il devient au cours des années 70 le symbole de la lutte contre la peine de mort. En 1981, avec le retour de la gauche au pouvoir, il devient garde des sceaux et s’empressera d’œuvrer à l’abolition de la peine de mort. Il y parviendra en septembre 1981. Après son départ du ministère de la justice en 1986, il est nommé président du Conseil Constitutionnel pour 9 ans. Il enchaîne ensuite avec 2 mandats de sénateur des Hauts de Seine. Il est aujourd’hui retourné à la vie civile, au sein d’un cabinet de consultations juridique Corpus consultants. Robert Badinter est l’auteur de plusieurs ouvrages parmi lesquels « L’exécution » en 1973, « L’abolition » en 2000 et « Contre la peine de mort » en 2006. -

Trial by Media ( Female )

Trial-by-Media Trial-by-Media Table Of Contents About .............................................................. 3 Amanda Knox ........................................................ 4 Analysis of Women executed in United States since 1976 ........................... 5 Ann Rule ............................................................ 8 Arguments against death penalty ........................................... 9 Arizona-perverts ..................................................... 11 Ashley Smith ......................................................... 12 Bad Lawyering ....................................................... 13 Baddies ............................................................. 17 Bradley Cooper ....................................................... 19 Break the chain ....................................................... 20 Carlos DeLuna ....................................................... 21 Case Rating .......................................................... 22 Cases by Country or State ................................................ 23 Claudine Longet ...................................................... 26 Cold Case ........................................................... 27 Congress Release Project ................................................ 28 Craigavon Two ....................................................... 29 Darlie Routier ........................................................ 30 David Camm ......................................................... 31 Debra Milke ........................................................ -

Pull-Over Rouge

Fictions Documentaires Le thème de la condamnation à mort est largement traité dans le cinéma. C'est le dernier plan image pour bien des malfrats et assassins, personnages principaux des films policiers et thrillers : une forme de « happy end » pour la société, puisque justice est faite. A l'issue d'une longue enquête ou d'une traque, l'assassin est enfin trouvé et sanctionné. (Ascenseur pour l'échafaud, Deux hommes dans la ville, Nous sommes tous des assassins) C'est l'intrigue pour un grand nombre de films de suspense, dans laquelle l'enquête est portée par un personnage principal « justicier ». Le plus souvent avocat ou journaliste, il se démène pour rétablir la justice, et en conséquence sauver la vie d'une personne injustement condamnée. (Juste cause, Je veux vivre, l'invraisemblable vérité, Meurtre à Alcatraz, Made in the USA) C'est un trouble que diffusent les films aux ressorts psychologiques complexes, où domine le sentiment d'incompréhension face à des actes qu'aucune logique ne vient expliquer. Des personnages à la frontière de la désociabilisation, de la folie. (The barber l'homme qui n'était pas là, Tu ne tueras point, De sang-froid) Militant de son époque, et surtout aux Etats-unis, le cinéma dénonce la discrimination dans l'énoncé de la justice, qu'elle soit raciale (Un coupable idéal, Amistad) ou sociale (le couloir de la mort, Dancer in the dark), ainsi que les affaires politiques (Sacco & Vanzetti, toute ma vie en prison). Il avertit également les Occidentaux du danger d'être impliqué dans une affaire de drogue (Bangkok aller simple, Force majeure, Trop jeune pour mourir). -

The Emerging Role of Innocence Projects in the Correction of Wrongful Conviction in Australia

Investigating Innocence: The Emerging Role of Innocence Projects in the Correction of Wrongful Conviction in Australia Author Weathered, Lynne Published 2003 Journal Title Griffith Law Review Copyright Statement © 2003 Griffith Law School. The attached file is reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/6223 Link to published version https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10383441.2003.10854511 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au INVESTIGATING INNOCENCE The Emerging Role of Innocence Projects in the Correction of Wrongful Conviction in Australia * Lynne Weathered DNA technology has uncovered the significant problem of wrongful conviction in the United States. Australians tend to have great faith in our criminal justice system; however, innocent people have also been wrongly convicted in this country. As a society, we must never become complacent about our criminal justice system: we must continually address areas likely to be relevant to the incidence of wrongful conviction, and we need mechanisms for the proper review of claims of innocence. Following in the footsteps of Innocence Projects in the United States, Innocence Projects in Australia are emerging as a resource for the investigation of claims of wrongful conviction with the aim of freeing innocent persons from incarceration. The majority of wrongful conviction claims will not involve DNA evidence, making the investigative work of Innocence Projects more complex and time-consuming, but also a task in which student resources are particularly valuable. To enhance the effectiveness of addressing claims of wrongful conviction, adoption of legislation or procedures is required. -

Jacques Vergès, the Devil's Advocate

Jacques Vergès, Devil’s Advocate A Psychohistory of Vergès’ Judicial Strategy Faculty of Law, McGill University, Montreal April 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Civil Law © Jonathan Widell, 2012 Abstract This study undertakes a psychohistory of French criminal defence lawyer Jacques Vergès’ judicial strategy. .His initial articulation of his judicial strategy in his book De la stratégie judiciaire in 1968 continues to inform his legal career, in which he has defended a number of controversial clients, most notably that of Gestapo officer Klaus Barbie in the 1987 trial. Vergès distinguished two types of judicial strategy in his 1968 book: rupture and connivence. Both strategies should be understood out of Vergès’ Marxist influences. This study looks into the coherence of his career in light of his initial articulation of judicial strategy and explores the shift in emphasis of his strategy from the defence of a cause to that of a person. The study adopts a three-level approach. It considers, first, Vergès’ discourse of his strategy, second, the world politics that shaped his discourse, and third, Vergès’ biography. First, Vergès’ strategy grew out of the duality of rupture and connivence and transformed into what we call devil’s advocacy, in which Vergès pits an accused (as an individual) against the justice system. Devil’s advocacy culminated in his defence of Barbie. After his defence of Barbie, Vergès pitted himself against the justice system so that his own notoriety was reflected to his clients rather than the other way around. -

La Guillotine

CAUSERIE DU 12 MARS 2020 PAR JEAN-DENIS VICTOR LA GUILLOTINE SOMMAIRE • Pourquoi la guillotine • Petite rétrospective de la peine de mort • Histoire de la guillotine • Les excès de la Révolution Française • Acheminement et montage • Fonctionnement • Les derniers guillotinés en France • Les lignées de bourreaux • L’abolition de la peine de mort Je ne cite que quelques anecdotes historiques, sans les développer, car ce n’est pas le sujet. AS SOCIATION DES COLLECTIONNEURS POITEVINS (A.C.P.) PAGE 1 POURQUOI LA GUILLOTINE ? Ce n’est pas par esprit morbide, mais cet outil de triste réputation fait, qu’on le veuille ou non, partie de l’Histoire de France, de notre Histoire. Toujours intéressé au droit et à la justice, j’ai voulu ce petit rappel. Je ne l’aurais pas fait si la peine de mort existait encore. PETITE RETROSPECTIVE DE LA PEINE DE MORT Depuis la nuit des temps, l’inventivité de l’Homme n’a eu de limites, pour punir son prochain, non seulement par la mort, mais en lui infligeant les pires souffrances avant que celle-ci ne survienne, à petit feu comme on pourrait le dire. Vous voulez quelques exemples ? Supplice de Brunehaut en 613 / Attachée vivante à un cheval sauvage et traînée par celui-ci. AS SOCIATION DES COLLECTIONNEURS POITEVINS (A.C.P.) PAGE 2 LA CRUXIFICTION Connue surtout pour la mort de Jésus Christ, et remise « à l’honneur » par les Romains. Existait en Perse, chez les Grecs, les hébreux, etc… L’ECORCHEMENT L'écorchement est une manière de tuer un condamné en lui retirant la peau (épiderme, derme, hypoderme) jusqu'au fascia musculaire (enveloppe des muscles). -

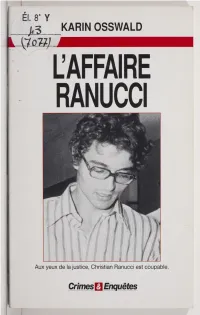

L'affaire Ranucci

L'AFFAIRE RANUCCI KARIN OSSWALD L'AFFAIRE RANUCCI Crimes & Enquêtes Collection dirigée par Paul Lefèvre © Éditions J'ai lu, 1994 Ce matin-là s'est peut-être commis l'acte le plus hor- rible, qu'une société démocratique peut générer : l'assas- sinat légal, réfléchi, décidé d'un innocent. Ce matin-là, le 28 juillet 1976, Christian Ranucci a été exécuté dans la cour des Baumettes, à Marseille. Et la question subsiste toujours de savoir si l'assas- sinat d'un innocent a été voté pour réparer l'assassinat d'une autre innocente : Maria-Dolorès Rambla avait huit ans lorsqu'un individu l'a enlevée, près de chez ses parents, le 3 juin 1974, et l'a poignardée quelques heures plus tard. Après deux jours d'audience et cinq heures de déli- béré, les jurés de la cour d'assises d'Aix-en-Provence ont estimé, en leur âme et conscience, que Christian Ra- nucci était cet homme. L'était-il vraiment ? Le doute est tel, dans cette affaire, qu 'il fallait repartir des premiers éléments de l'enquête et refaire tout le par- cours de l'information pour discerner la réalité. Travail difficile après tant de polémiques, de passions et de heurts... Karin Osswald, journaliste d'investigation et chef du bureau de Radio Monte-Carlo à Marseille, a voulu savoir si la justice était passée ou si un homme était mort pour rien... Paul LEFÈVRE Les obsèques de Marie-Dolorès Rambla sont pré- vues à 16 heures, mais dès le début de l'après-midi, une foule compacte et silencieuse se presse dans les allées du cimetière Saint-Pierre. -

20 Minutes to Death: Record of the Last Execution in France The

20 Minutes to Death: Record of the Last Execution in France The following document is a written record of convicted killer Hamida Djandoubi's last moments before he was guillotined in a Marseilles prison on September 10, 1977. This record -- dated September 9 -- was written by a judge appointed to witness the execution. Djandoubi's execution was the last execution carried out in France before capital punishment was abolished in 1981. Then-President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, who had voiced his "loathing for the death penalty" before he was elected to office, flatly turned down Djandoubi's appeal for clemency and chose to let "Justice run its course", as he did on two previous instances (Christian Ranucci, executed on July 28, 1976 and Jérôme Carrein, executed on June 23, 1977). Hamida Djandoubi, a Tunisian national, was sentenced to death for killing his former lover, Elisabeth Bousquet. He was executed in Marseilles' Baumettes prison in September 1977. The following text was written on the night of the execution by judge (juge d'instruction) Monique Mabelly. Mabelly later entrusted the document to her son, who ultimately passed it on to Robert Badinter, the ex-Minister for Justice who successfully campaigned for the abolition of the death penalty in France. Badinter eventually gave the document to the French newspaper Le Monde, which published it on October 9, 2013. The text below is a translation. The French original can be found here. 9th September 1977 Execution of Djandoubi, Tunisian citizen. At 3:00 p.m., [presiding] judge R. notified me that I had been appointed to assist with the execution. -

Michel Fourniret Assure Être Victime "D'acharnement"

La Provence PAGE : LP - 15.MARSEILLE - 26 - 27/01/06 - COUL : Composite OP : LAPROVENCE - 27/01/06 10:39 26 ❙ PROVENCE ❙ Vendredi 27 Janvier2006 NATURE JUSTICE CELEBRITES Desloupsattaquentprèsd’unvillage 10ansferme pour le viol de sespetites-filles L’accusatricedeJohnnyfaitappel L La dépouille d’une femelle de mouflonaétédécouvertepar L Unprofesseur retraitéde73 ansaétécondamné jeudi àdix L L'hôtessequiaccuseJohnnyHallydayde l'avoirviolée sur un despromeneurs dimanche dernierdansleHaut-Verdon,enbordu- ansde réclusion criminelle parlacour d'assisesduVaràDra- yachten avril 2001afaitappel de ladécision de non-lieurendu red’unepisteforestièremenantàunhameau,àunkilomètreseu- guignanpour avoirviolé etagressédeux de sespetitesfilles, parunjuge d'instruction niçois.Marie-Christine Vosouhaiteen lementduvillage de Villars-Colmars.Selon,le technicienlocal âgéesde 7et5ansàl'époquedesfaits.Dèsl'ouverturedesdé- effetunréexamen de cedossier.L'affaireseraportée devantles de l’ONF quiaprocédé auconstat," il s’agitsansaucundoute bats,l'accusé,habitantàPlan-du-Castellet(Var),avaitreconnu jugesde lacour d'appel d'Aix-en-Provence. Aujourd’huiâgée de d’une attaquedeplusieurs loupsdanslanuitde samedi àdiman- lesfaits etdemandé pardon àsesvictimesaujourd’huiâgée de 37 ans,Mlle Vo,avaitportéplaintepour viol en avril 2002,en che" sanstoutefoispouvoiren préciserle nombre. C’est lapre- 23 anset16ans.Aucours desdébats,il aétéévoquélepassé accusantson ex-employeur de l'avoiragressée sexuellementau mièrefoisdansle Haut-Verdon qu’une attaquedemeuteest ducondamné quiterrorisaitsafamille