Transportation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bid Opportunities

L SMAL BUBUSINSINEXCHANGCHANGEE SSNORTHEASNORTHEASTT • NEWS • INFO EXTRA • BIDS Volume 37, Edition 5E • February 12, 2021 Published by SBE, Inc. • DBE/MBE/SBE 1984 36 2020 Best Practices for Hiring Subcontractors look at those projects and check their references. By Danielle Levine Hire the subcontractor that has its next jobs lined up. If this subcontractor has a waiting list, it is more Hiring the wrong subcontractor can create than likely that they know what they are doing. a variety of consequences, especially for small contractors. Here are six points to consider when 2. Define scope of work hiring subcontractors. Outline a clear, detailed, scope of work so that when evaluating the subcontractor there is 1. Be selective when hiring a well-defined set of requirements to check their Never settle for a subpar subcontractor. Vetting qualifications against. Define the scope of the ahead of time is critical to success. Find out: project verbally and in writing. Not only does • If they have the same goals as the company this serve as a record, but it also allows the • How ambitious the subcontractor is to get the subcontractor to look at each piece of it. The process job done of defining the scope of work is an opportunity for • If the subcontractor is known in the industry the subcontractor to: and has a good reputation • Identify conflicts or challenges associated • What their capabilities are with their scope of work • Whether they can follow simple directions, • Speak about the proposal e.g., proposal submission procedures • Come to the table with solutions, ideas, and • If this just another job or will they engage in problems that could occur subcontractor against multiple criteria. -

The New York City Waterfalls

THE NEW YORK CITY WATERFALLS GUIDE FOR CHILDREN AND ADULTS WELCOME PLAnnING YOUR TRIP The New York City Waterfalls are sited in four locations, and can be viewed from many places. They provide different experiences at each site, and the artist hopes you will visit all of the Waterfalls and see the various parts of New York City they have temporarily become part of. You can get closest to the Welcome to THE NEW YORK CIty WATERFALLS! Waterfalls at Empire-Fulton Ferry State Park in DUMBO; along the Manhattan Waterfront Greenway, north of the Manhattan Bridge; along the Brooklyn The New York City Waterfalls is a work of public art comprised of four Heights Promenade; at Governors Island; and by boat in the New York Harbor. man-made waterfalls in the New York Harbor. Presented by Public Art Fund in collaboration with the City of New York, they are situated along A great place to go with a large group is Empire-Fulton Ferry State Park in Brooklyn, which is comprised of 12 acres of green space, a playground, the shorelines of Lower Manhattan, Brooklyn and Governors Island. picnic benches, as well as great views of The New York City Waterfalls. These Waterfalls range from 90 to 120-feet tall and are on view from Please see the map on page 18 for other locations. June 26 through October 13, 2008. They operate seven days a week, You can listen to comments by the artist about the Waterfalls before your from 7 am to 10 pm, except on Tuesdays and Thursdays, when the visit at www.nycwaterfalls.org (in the podcast section), or during your visit hours are 9 am to 10 pm. -

12 Clark Street OWNED by SAME FAMILY SINCE 1952 OFFERING PROCESS

BROOKLYN HEIGHTS 12 Clark Street OWNED BY SAME FAMILY SINCE 1952 OFFERING PROCESS EXCLUSIVE REPRESENTATION Newmark Knight Frank has been DISCLAIMER exclusively retained to represent the Seller in the sale of 12 Clark Street (“Property”). All inquiries about the This Memorandum has been prepared by Agent for use by a limited number of Offering for the Property should be parties, and does not purport to provide a necessarily accurate summary of the directed to the Newmark Knight Frank Property or any of the documents related thereto, nor does it purport to be all- Marketing Team. inclusive or to contain all of the information which prospective investors may need or desire. All projections have been development by Seller and Agent, and designated sources, and are based upon assumptions relating to the general PROPERTY TOURS economy, competition and other factors beyond the control of Seller, and Prospective purchasers will have the therefore are subject to variation. No representation is made by Seller or Agent as opportunity to visit the Property on to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein, and nothing scheduled tour dates and must be contained herein is, or shall be relied on as, a promise or representation as to the accompanied by a representative of future performance of the Property. Although the information contained herein is Newmark Knight Frank. Prospective believed to be correct, Seller, Seller’s agents, attorneys, representatives, and its purchasers should not contact the site employees, disclaim any responsibility for inaccuracies, and expect prospective staff directly. purchasers to exercise independent due diligence in verifying all such information. -

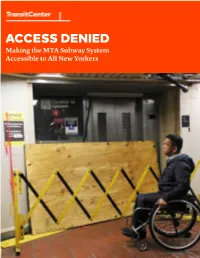

ACCESS DENIED Making the MTA Subway System Accessible to All New Yorkers SHARE of STATIONS with Elevator Access 23%

ACCESS DENIED Making the MTA Subway System Accessible to All New Yorkers SHARE OF STATIONS with elevator access 23% NUMBER OF OUTAGES a rider can expect to encounter in one year at the current elevator 90 availability of 95.7% NUMBER OF OUTAGES a rider can expect to encounter in one year at the desired 10 elevator availability of 99.5% PERCENT OF NYC RESIDENTS in 2030 who will be 65 or older 15% AVERAGE OUTAGES 25 elevators througout the system experience on a daily basis YEARS UNTIL the NYC subway system will be 70 fully ADA accessible at the current pace of elevator construction LAST UPDATE the MTA made to its list 1994 of stations in need of accessibility upgrades COST PER RIDE $70 for the MTA to provide para- transit service to New Yorkers unable to use the subway Data collected from the MTA for July 2014-June 2015 & the NYC Department of City Planning 1. Introduction The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) and New York City Transit (NYCT) operate the least accessible major subway system in the country for people who require stair-free access. Nearly 30 years after the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990, only 23% of the city’s subway stations have elevators. These elevators break down often, rendering even fewer stations accessible to those with mobility impairments. The paucity of accessible stations combined with this high degree of unreliability makes journeys unpredictable, vastly extending travel times, rerouting riders, and making trip planning impossible. These elevators are also notoriously dirty and malodorous, a persistent problem that is symptomatic of overall neglect. -

Document.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY FINANCIAL OVERVIEW LOCATION OVERVIEW BESEN ADVISORY TEAM Amit Doshi Executive Director (212) 951-8401 [email protected] Shallini Mehra Senior Director (212) 951-8414 [email protected] Jonathan Shainberg Director (646) 424-5331 [email protected] Ronald H. Cohen Chief Sales Officer (646) 424-5317 [email protected] Paul J. Nigido Senior Financial Analyst (646) 424-5350 [email protected] Besen & Associates 381 Park Avenue South 15th Floor New York, NY 10016 (212) 689-8488 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Besen & Associates, as exclusive agent for Ownership, is pleased to offer for sale 35 Pineapple Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201 (The “Property”), also known as 102 Hicks Street, a corner property which consists of a pristine 5-story, mixed-use elevator building with 11 free market apartments and 1 retail store, Joe Coffee Company. Built circa 1900, this architecturally distinct property contains 13,342± SF and is located in Historic Brooklyn Heights, Brooklyn’s premiere and most desirable neighborhood. The building is situated on a parcel measuring 25’ x 101’ on the northwest corner of Pineapple Street and Hicks Street. Just a short walk to the Brooklyn Bridge Park and The Brooklyn Heights Promenade, the Property offers easy access to the BQE and is within walking distance to the [A, C] subway station at Cadman Plaza and the [2,3] Clark Street subway station at Henry Street. One of the first neighborhoods outside of Manhattan after crossing the Brooklyn Bridge, Brooklyn Heights offers a cozy residential feel with all of the conveniences of city life. The charming area features tree-lined streets with meticulously restored row houses, cobblestone side streets, and a thriving mix of commercial and community-focused businesses. -

Corvus Review

CORVUS REVIEW ISSUE 8S 2017 2 TOC A. Mughal 3 S. Roberts 140 J. Schueler 235 C. Kosch 9 J. Hunter 142 M. Minassian 236 G. Jeffers 12 N. Kovacs 148 R. Flanagan 237 T. Elson 17 T. Rutkowski 151 Flash Fiction Competition Winners B. Iozzia 21 B. Diamond 153 Hon. Mention: A. Trodd 238 B. Stanwyck 23 F. Miller 157 2nd Place: C. Stanley 240 J. Manzano 25 K. Casey 166 1st Place: R. Reeves-Murray 242 E. Ferry 31 K. Hanson 168 S. Leet 32 J. Butler 171 Bio’s 244-E N. Orts 33 R. Massoud 173 T. Mihocik 41 C. Valentza 178 T. Frank 47 D. Vitucci 179 J, Serri 52 J. Hickey 183 B. Petersen 58 J. Bradley 188 M. Waldman 66 S. F. Greenstein 189 S. Slavin 75 J. Mulhern 195 C. Wellons 77 B. Varghese 201 R. Heby 78 K. Maruyama 208 A. O’Brien 80 Poetry P. Beckstrom 83 E. Smith Sleigh 216 J. Bristow 85 M. L. Johnson 217,218 D. Marsh 88 (NF) B. Abbott 219 C. Palmer (NF) M. Ehrlich 220 R. Hemmell 97 (SF) D. Hearne 221 K. Shields 99 R. Stout 222 J. Half-Pillow 101 D. Mager 223 M. Wren 109 K. Hemmings 224, 225 D. Clark 110 N. Rounds 226 P Kauffmann 112 K. Dronsfield 228 J. Hill 115 J. Zola 229 J.Gorman 117 P. Ilechko 230 B. Taylor 124 N. Crick 231 M. Ferro 131 I. Orpi 232 M. Laing 133 M. Danowsky 233,234 3 The Ear Alisha Mughal I left the house that morning because I felt trapped inside — stifled within those whitewashed walls, looming over me blank and silent and expectant. -

YARDS AWAY Ratner Train Relocation Could Affect Eminent Domain Fight NOT JUST NETS the NEW BROOKLYN

WIN A HONEYMOON CRUISE — ENTER AT THEBROOKLYNBRIDE.COM BROOKLYN’S REAL NEWSPAPERS Including The Brooklyn Heights Paper, Carroll Gardens-Cobble Hill Paper, DUMBO Paper, Fort Greene-Clinton Hill Paper and the Downtown News Published every Saturday — online all the time — by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington St, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2005 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 18 pages •Vol.28, No. 25 BWN •Saturday, June 18, 2005 • FREE YARDS AWAY Ratner train relocation could affect eminent domain fight NOT JUST NETS THE NEW BROOKLYN By Jess Wisloski retail and as many as 7,300 units The Brooklyn Papers of housing. To build the project, the devel- If he wants to build a new oper will need to purchase air home for his New Jersey rights over roughly 11 acres of Nets basketball team atop MTA rail yard property. The re- rail yards at Atlantic and maining 13 acres are owned or Flatbush avenues, developer controlled by Ratner or else are Bruce Ratner will have to subject to state condemnation for pay for more than air space Ratner’s use under eminent do- over the Long Island Rail main laws. Road tracks — he’s also The MTA did not sign on to the going to have to help pay to memorandum of understanding move those tracks. (MOU) agreed to in March by the According to an agreement city, state and Ratner. The MTA is negotiated among the city, state negotiating separately with the de- and Forest City Ratner Compa- veloper, said Forest City Ratner spokeswoman Lupe Todd. -

Premier Retail Availabilities 85 Jay Street Brooklyn, NY

85 Jay Street Brooklyn, NY Premier Retail Availabilities Building Details Delivering 2021 60,000 SF Premier Retail Available Industrial-Style Storefronts Inspired by the Manhattan Bridge 30-Foot Wide Tree-lined Sidewalks 400+ Parking Spaces On-site public garage A Full City Block Two 21-story Residential Towers 700+ Residences Residential condominium and rental apartments Designed by Morris Adjmi Architects 1 The Shops at Front & York are located adjacent to the York Street Station (F train), and a short walk from the High Street Station (A & C Trains) and Pier I/DUMBO Ferry stop. The building is also within minutes of DUMBO’s major transportation connections including the Brooklyn Bridge, Manhattan Bridge and Brooklyn-Queen’s Expressway. 2 Neighborhood Features 14 2 3 4 15 7 6 16 Dumbo Pier 1 5 1 Ferry Landing 10 Minute Walk 8 13 9 17 11 12 10 F York Street Station 1 Minute Walk 3,927,129 Annual Ridership Clark Street Station 2 3 13 Minute Walk High Street Station 1,781,419 Annual Ridership A C 9 Minute Walk 3,536,860 Annual Ridership 1 1 Hotel 2 Brooklyn Bridge Park 3 Jane’s Carousel 4 Pebble Beach 5 St. Ann’s Warehouse 12 Minute Walk 9 Minute Walk 8 Minute Walk 7 Minute Walk 8 Minute Walk Amenities 6 Dumbo House 7 Empire Stores 8 Dumbo Archway 9 Brooklyn Flea 6 Minute Walk 6 Minute Walk 3 Minute Walk 2 Minute Walk 10 Pierhouse 11 30 Front Street 12 98 Front Street 13 168 Plymouth Street New 10 Story, 106-Unit Condominium 26 Story, 78-Unit Condominium 11 Story, 165-Unit Condominium 10 Story, 46-Unit Condominium Development 14 1 John -

BATTLING for BROOKLYN HEIGHTS by Martin L

1 BATTLING FOR BROOKLYN HEIGHTS by Martin L. Schneider Introduction Anthony C. Wood Preservation in New York City has achieved such a level of success that it risks being taken for granted by new generations of New Yorkers; a fate that could translate into a future of unnecessarily lost buildings and disfigured historic neighborhoods. December 2009 saw the designation of the city’s 100th historic district and 2010 marks the 45th anniversary of the passage of New York City’s hard won landmarks law. Preservation in New York certainly has come of age. Contributing to the possibility that future New Yorkers may misguidedly assume preservation is now the city’s default policy position (tragically ignoring the cold reality that the blood of most New York powerbrokers still races at the mere mention of real estate development) is the fact that preservationists have largely failed to tell their stories of the often heroic efforts required to save the city’s landmarks and historic districts. One wonderful exception to this is the story of the saving of Brooklyn Heights. Thanks to the prescience and dedication of those involved in this battle, the struggle to save Brooklyn Heights is the best documented of all New York City’s preservation sagas. Today we are fortunate to have available to us extensive newspaper accounts from that time, numerous original documents, oral histories and personal remembrances. If only the same could be said for other significant chapters in preservation’s history. Thanks to Martin L. Schneider, we now can add to the existing material on Brooklyn Heights, this compelling narrative “Battling for Brooklyn Heights.” Told through the eyes of a witness to history and capturing the emotions of one who lived through it, Mr. -

Download The

Assemblymember 52nd District Announcements & Upcoming Events No vember 2019 A Message from Jo Anne… Clark Street Station Survey Results: Earlier this year, MTA New York City Transit’s (NYCT) identified a critical need to replace the three elevators that serve the 2/3 Clark Street subway station in Brooklyn Heights. NYCT has proposed two approaches to this work: (i) replacing all elevators simultaneously, which would require shutting the station entirely for 8 months, or (ii) replacing the elevators one at a time. Under this latter approach, two options were proposed: a 24- month project, permitting the station to be open 24 hours a day throughout the construction period (except during emergencies when one of the two remaining elevators fails) or a 22-month project, permitting the station to be open during peak hours (again, except during emergencies). I worked with Senator Brian Kavanagh, Congresswoman Nydia Velázquez, Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, and City Council Member Stephen Levin to host a community forum where NYCT President Andy Byford discussed the possible options for renovation. In order to gauge public opinion regarding the approaches, our offices also conducted a survey at the forum, at the station, and online. The survey results include the following highlights: Overall, 62% of respondents preferred one-elevator-at-a-time replacement, with either a 22- or 24-month duration, while 38% preferred full closure with an 8-month duration. While the great majority (86%) of survey respondents completed the survey at the station or online, it is worth noting that of the 14% who responded at the forum, most tended to differ from the opinions of the majority who completed the survey at the station or online. -

Mayor Boothe Begins Second Term; Mrs

—-HOW TO GET THE LEADER-^ Just Fill in the Form On Page 10 And Return It to Us! — Sen-inn the Town Sinve 1890 — vsrstmo YEAR Stand ClMt Paauif Paidai Unc/Idd. SJ. Thursday, January 5,199S 232-4407 FORTY CENTS TEMPORARY BUDGET OF $5.365.400 ADOPTED BY COUNCIL Mayor Boothe Begins Second Term; Mrs. Vernick Sworn Into Office As New First Ward Councilwoman Governing Body Unanimously Approves Appointments; Third Ward Vacancy Could Be Filled This Tuesday Hy PAUL J.PEYTON ccssful campaign for State Assem- Bureau of Securities. Tiie council is .fyr. i.jf/v Wttlfrnftir JTir WntfirlitUuA,i blyman in the 22nd L-cgislalive Dis- expected lo fill (he vacancy at its next TheTown Council Chambers were Iricl. Mr. Gruba, in (urn, was ap- meeting this Tuesday. January 10. packed on Tuesday nighl as Ma>or pointed to fill the unexpired term of The Mayor gave out several reso- Garland C. "Bud" Boothe, Jr. took Mayor Boothe for the Second Ward lutions to residents who have chosen the oath of office for his second lerm Mayor Boothe was then elected to his not In be reappointedthis year. Among lioin Township Clerk, Mrs. Joy C. first three-year term in November ol the long list was Hcth Pollack as un Vrecland.Alsosworn into office were 1991. Lilternale member of the Board ol newly elected First Ward Council Councilman Grubu was elected lo Adjustment, Charles Morrison, who woman, Mrs. Gail Vernick, and re- his second term on the council white served on Ihe Local Assistance Board elected incumbents James J. -

Snapshot of Snowstorm Complaints to the Office of the Public Advocate

72 Hour Storm Watch: Snapshot of Snowstorm Complaints to the Office of the Public Advocate December 30, 2010 Visit the Office of the Public Advocate on the web at advocate.nyc.gov, call the Office at 212-669-7250 or email at [email protected] OFFICE OF THE NEW YORK CITY PUBLIC ADVOCATE Bill de Blasio Public Advocate for the City of New York Prepared By: Emma Wolfe Chief of Staff Ursulina Ramirez Senior Policy Associate Irum Taqi, Esq. Deputy General Counsel Wiley Norvell Press Secretary 1 Introduction On December 26, 2010 New York City experienced the sixth largest snowstorm in City history1, with snow falls upward of 20 inches2 in some neighborhoods. The storm had a crippling effect on many of the City’s vital services such as transportation, emergency response systems and access to hospitals. Additionally, it brought many neighborhoods to a halt, especially those in the outer-boroughs. Although it is difficult to predict the severity of large storms, the lack of snow clearance in many areas of the City raises concerns over the preparation and planning for this winter’s first large snowstorm. Despite the difficulty in predicting the impact of storms, it has become overwhelmingly evident that the City was ill-prepared to handle such a large and fast approaching storm, and there is minimal public information about the City’s planning and preparation for the storm and how it will improve its efforts in the future. During the seventy-two hour period after the storm hit New York City, the Office of the Public Advocate (“Office”) catalogued nearly 950 complaints from anxious and stranded constituents due to the impact of the snowstorm.