Picaresque Necessity: Episodic Narrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wicked Actions and Feigned Words: Criminals, Criminality, and the Early English Novel Author(S): Lennard J

Wicked Actions and Feigned Words: Criminals, Criminality, and the Early English Novel Author(s): Lennard J. Davis Reviewed work(s): Source: Yale French Studies, No. 59, Rethinking History: Time, Myth, and Writing (1980), pp. 106-118 Published by: Yale University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2929817 . Accessed: 24/01/2013 12:34 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Yale University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Yale French Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded on Thu, 24 Jan 2013 12:34:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Lennard J. Davis Wicked Actions and Feigned Words: Criminals,Criminality, and the Early EnglishNovel In 1725 JamesArbuckle wrote an articlein the Dublin Journalwhich condemned the reading of novels. He attacked those "fabulous adventuresand memoiresof pirates,whores, and pickpocketswhere- withfor sometime past thepress has so prodigiouslyswarmed." What particularlygalled Arbucklewas thatmembers of the middleclasses were being attractedto the kindof literaturethat had formerlybeen -

Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos Nº 337-338, Julio-Agosto 1978

CUADERNOS HISPANOAMERICANOS MADRID JULIO-AGOSTO 1978 337-338 CUADERNOS HISPANO AMERICANOS DIRECTOR JOSÉ ANTONIO MARAVALL JEFE DE REDACCIÓN FÉLIX GRANDE HAN DIRIGIDO CON ANTERIORIDAD ESTA REVISTA PEDRO LAIN ENTRALGO LUIS ROSALES DIRECCIÓN, SECRETARIA LITERARIA Y ADMINISTRACIÓN Centro Iberoamericano de Cooperación Avenida de los Reyes Católicos Teléfono 244 06 00 MADRID CUADERNOS HISPANOAMERICANOS Revista mensual de Cultura Hispánica Depósito legal: M 3875/1958 DIRECTOR JOSÉ ANTONIO MARAVALL JEFE DE REDACCIÓN FÉLIX GRANDE 337-338 DIRECCIÓN, ADMINISTRACIÓN Y SECRETARIA Centro Iberoamericano de Cooperación Avda. de los Reyes Católicos Teléfono 244 06 00 MADRID INDICE NUMEROS 337-338 (JULIO-AGOSTO 1978) HOMENAJE A CAMILO JOSE CELA Páginas JOSE GARCIA NIETO: Carta mediterránea a Camilo José Cela ... 5 FERNANDO QUIÑONES: Lo de Casasana 13 HORACIO SALAS: San Camilo 1936-Madrid. San Rómulo 1976-Bue- nos Aires 17 PEDRO LAIN ENTRALGO: Carta de un pedantón a un vagabundo por tierras de España 20 JOSE MARIA MARTINEZ CACHERO: El septenio 1940-1946 en la bi bliografia de Camilo José Cela : 34 ROBERT KIRSNER: Camilo José Cela: la conciencia literaria de su sociedad • 51 PAUL ILIE: La lectura del «vagabundaje» de Cela en la época pos franquista 61 EDMOND VANDERCAMMEN: Cinco ejemplos del ímpetu narrativo de Camilo José Cela 81 JUAN MARIA MARIN MARTINEZ: Sentido último de «La familia de Píí ^C'tirii DtJ3tt&¡> Qn JESUS SANCHEZ LOBATO: La adjetivación "en «La familia de Pas cual Duarte» 99 GONZALO SOBEJANO: «La Colmena»: olor a miseria 113 VICENTE CABRERA: En busca de tres personajes perdidos en «La Colmena» 127 D. W. McPHEETERS: Tremendismo y casticismo 137 CARMEN CONDE: Camilo José Cela: «Viaje a la Alcarria» 147 CHARLES V. -

A Rhetorical Study of Edward Abbey's Picaresque Novel the Fool's Progress

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2001 A rhetorical study of Edward Abbey's picaresque novel The fool's progress Kent Murray Rogers Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Rogers, Kent Murray, "A rhetorical study of Edward Abbey's picaresque novel The fool's progress" (2001). Theses Digitization Project. 2079. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2079 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A RHETORICAL STUDY OF EDWARD ABBEY'S PICARESQUE NOVEL THE FOOL'S PROGRESS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Kent Murray Rogers June 2001 A RHETORICAL STUDY OF EDWARD ABBEY'S PICARESQUE NOVEL THE FOOL,'S PROGRESS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Kent Murray Rogers June 2001 Approved by: Elinore Partridge, Chair, English Peter Schroeder ABSTRACT The rhetoric of Edward Paul Abbey has long created controversy. Many readers have embraced his works while many others have reacted with dislike or even hostility. Some readers have expressed a mixture of reactions, often citing one book, essay or passage in a positive manner while excusing or completely .ignoring another that is deemed offensive. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

Brad a Mante

B radA mante Revista de Letras, 1 (2020) Hablo de aquella célebre doncella la cual abatió en duelo a Sacripante. Hija del duque Amón y de Beatriz, era muy digna hermana de Rinaldo. Con su audacia y valor asombra a Carlos y Francia entera aplaude su coraje, que en más de una ocasión quedó probado, en todo comparable al de su hermano. Orlando furioso II, 31 B radA mante Revista de Letras, 1 (2020) | issn 2695-9151 BradAmante. Revista de Letras Dirección Basilio Rodríguez Cañada - Grupo Editorial Sial Pigmalión José Ramón Trujillo - Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Comité científico internacional M.ª José Alonso Veloso - Universidade de Santiago de Compostela Carlos Alvar - Université de Genève (Suiza) José Luis Bernal Salgado - Universidad de Extremadura Justo Bolekia Boleká - Universidad de Salamanca Rafael Bonilla Cerezo - Universidad de Córdoba Randi Lise Davenport - Universidad de Tromsø (Noruega) J. Ignacio Díez - Universidad Complutense de Madrid Ángel Gómez Moreno - Universidad Complutense de Madrid Fernando González García - Universidad de Salamanca Francisco Gutiérrez Carbajo - Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia Javier Huerta Calvo - Universidad Complutense de Madrid José Manuel Lucía Megías - Universidad Complutense de Madrid Karla Xiomara Luna Mariscal - El Colegio de México (México) Ridha Mami - Université La Manouba (Túnez) Fabio Martínez - Universidad del Valle (Colombia) Carmiña Navia Velasco - Universidad del Valle (Colombia) José María Paz Gago - Universidade da Coruña José Antonio Pascual Rodríguez - Real Academia -

The Works of Daniel Defoe F08 Cripplegate Ed

THE WORKS OF DANIEL DEFOE IN SIXTEEN VOLUMES <ripplcrjate Etfttion THIS EDITION IS LIMITED TO ONE THOUSAND COPIES, EACH OF WHICH IS NUMBERED AND REGISTERED THE NUMBER OF THIS SET IS.... VARSITY PRESE ft* (Ptrttion HE O R K S 01 DANIEL DEFOE N D 8TAOD OV1ITOOH8 f A * 7 ' Ji X. 78 aoxl / dkrovered that presently there were, gouts in tht a great satisfaction to me PAGE 67 (fctsition THE WORKS OF DANI EL DEFOE THE LIFE AND STRANGE ADVENTURES OF ROBINSON CRUSOE COMPLETE IN THREE PARTS PAR T I NEW YORK MCMVIII GEORGE D. SPROUL Copyright, 1903, by THE UNIVERSITY PRESS UNIVERSITY PRESS JOHN WILSON AND SON, CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A. CONTENTS FAGB LIST or ILLUSTRATIONS vii INTRODUCTION . ix AUTHOR'S PREFACE . xxix The Life and of Adventures Robinson Crusoe . 1 The Journal 77 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS .TOOTING GOATS Frontispiece XURY DE&PATCHES THE LION THAT ROBINSON CRUSOE HAD DISABLED Page 30 THE FOOTPRINT ON THE SAND STARTLES ROBINSON CRUSOE 172 ROBINSON CRUSOE AND HIS MAN FRIDAY . 236 INTRODUCTION all the work of Daniel Defoe, even the earliest, shows that narrative was the kind of writing for which he NEARLYwas fitted by nature. Yet Defoe was more than a good story-teller. He was also a moral ist, an essayist, a journalist, an enthusiastic and fairly shrewd business man, a patriot, a trusted adviser of a king, and an unscrupulous political spy. Few readers of Robinson Crusoe realise what a varied and remarkable life was that of its author; few realise how late in life it was that he hit on the kind of writing which has given him his greatest fame. -

A Dictionary of Literary and Thematic Terms, Second Edition

A DICTIONARY OF Literary and Thematic Terms Second Edition EDWARD QUINN A Dictionary of Literary and Thematic Terms, Second Edition Copyright © 2006 by Edward Quinn All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Quinn, Edward, 1932– A dictionary of literary and thematic terms / Edward Quinn—2nd ed. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-8160-6243-9 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Criticism—Terminology. 2. Literature— Terminology. 3. Literature, Comparative—Themes, motives, etc.—Terminology. 4. English language—Terms and phrases. 5. Literary form—Terminology. I. Title. PN44.5.Q56 2006 803—dc22 2005029826 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can fi nd Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfi le.com Text design by Sandra Watanabe Cover design by Cathy Rincon Printed in the United States of America MP FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Contents Preface v Literary and Thematic Terms 1 Index 453 Preface This book offers the student or general reader a guide through the thicket of liter- ary terms. -

Catalogoqueleopedrodevaldivia40.Pdf

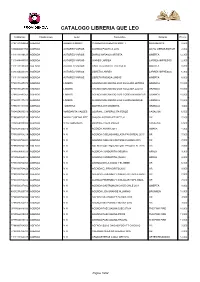

CATALOGO LIBRERIA QUE LEO CodBarras Clasificacion Autor Titulo Libro Editorial Precio 7798141020454 AGENDA ALBERTO MONTT CUADERNO ALBERTO MONTT MONOBLOCK 8,500 1000000001709 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS AGENDA POLITICA 2012 OCHO LIBROS EDITOR 2,900 1111111199121 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS DIARIO NARANJA ARTISTA OMERTA 12,300 1111444445551 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS IMANES LARREA LARREA IMPRESOS 2,900 1111111198988 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA GRANATE CALCULO OMERTA 8,200 3333344443330 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA LARREA LARREA IMPRESOS 6,900 1111111198995 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA ROSADA LINEAS OMERTA 8,500 7798071447376 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 ANILLADA LETRAS GRANICA 10,000 7798071447390 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 ANILLADA LLUVIA GRANICA 10,000 7798071447352 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 COSIDA BANDERAS GRANICA 10,000 7798071447338 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 COSIDA BOSQUE GRANICA 10,000 7798071444399 AGENDA . MAITENA MAITENA 007 MAGENTA GRANICA 1,000 7804654930019 AGENDA MARGARITA VALDES JOURNAL, CAPERUCITA FEROZ VASALISA 6,500 7798083702128 AGENDA MARIA EUGENIA PITE CHUICK AGENDA PERPETUA VR 7,200 7804654930002 AGENDA NICO GONZALES JOURNAL PIZZA PALIZA VASALISA 6,500 7804634920016 AGENDA N N AGENDA AMAKA 2011 AMAKA 4,900 7798083704214 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO ANILLADA PAVO REAL 2015 VR 7,000 7798083704221 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO CANTONE FLORES 2015 VR 7,000 7798083704238 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO CANTONE PAVO REAL 2015 VR 7,000 9789568069025 AGENDA N N AGENDA CONDORITO (NEGRA) ORIGO 9,900 9789568069032 AGENDA -

Does the Picaresque Novel Exist?*

Published in Kentucky Romance Quarterly, 26 (1979): 203-19. Author’s Web site: http://bigfoot.com/~daniel.eisenberg Author’s email: [email protected] Does the Picaresque Novel Exist?* Daniel Eisenberg The concept of the picaresque novel and the definition of this “genre” is a problem concerning which there exists a considerable bibliography;1 it is also the * [p. 211] A paper read at the Twenty-Ninth Annual Kentucky Foreign Language Conference, April 24, 1976. I would like to express my appreciation to Donald McGrady for his comments on an earlier version of this paper. 1 Criticism prior to 1966 is competently reviewed by Joseph Ricapito in his dissertation, “Toward a Definition of the Picaresque. A Study of the Evolution of the Genre together with a Critical and Annotated Bibliography of La vida de Lazarillo de Tormes, Vida de Guzmán de Alfarache, and Vida del Buscón,” Diss. UCLA, 1966 (abstract in DA, 27 [1967], 2542A– 43A; this dissertation will be published in a revised and updated version by Castalia. Meanwhile, the most important of the very substantial bibliography since that date, which has reopened the question of the definition of the picaresque, is W. M. Frohock, “The Idea of the Picaresque,” YCGL, 16 (1967), 43–52, and also his “The Failing Center: Recent Fiction and the Picaresque Tradition,” Novel, 3 (1969), 62–69, and “Picaresque and Modern Literature: A Conversation with W. M. Frohock,” Genre, 3 (1970), 187–97, Stuart Miller, The Picaresque Novel (Cleveland: Case Western Reserve, 1967; originally entitled, as Miller’s dissertation at Yale, “A Genre Definition of the Picaresque”), on which see Harry Sieber’s comments in “Some Recent Books on the Picaresque,” MLN, 84 (1969), 318–30, and the review by Hugh A. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan SOCIAL CRITICISM in the ENGLISH NOVEL

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 68-8810 CLEMENTS, Frances Marion, 1927- SOCIAL CRITICISM IN THE ENGLISH NOVEL: 1740-1754. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1967 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan SOCIAL CRITICISM IN THE ENGLISH NOVEL 1740- 175^ DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Frances Marion Clements, B.A., M.A. * # * * # * The Ohio State University 1967 Approved by (L_Lji.b A< i W L _ Adviser Department of English ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the Library of Congress and the Folger Shakespeare Library for allowing me to use their resources. I also owe a large debt to the Newberry Library, the State Library of Ohio and the university libraries of Yale, Miami of Ohio, Ohio Wesleyan, Chicago, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa and Wisconsin for their generosity in lending books. Their willingness to entrust precious eighteenth-century volumes to the postal service greatly facilitated my research. My largest debt, however, is to my adviser, Professor Richard D. Altick, who placed his extensive knowledge of British social history and of the British novel at my disposal, and who patiently read my manuscript more times than either of us likes to remember. Both his criticism and his praise were indispensable. VITA October 17, 1927 Born - Lynchburg, Virginia 1950 .......... A. B., Randolph-Macon Women's College, Lynchburg, Virginia 1950-1959• • • • United States Foreign Service 1962-1967. • • • Teaching Assistant, Department of English, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1962 ..... -

Rogues, Vagabonds and Sturdy Beggars, a New Gallery of Tudor

poofe 3^ebieiusi Rogues, Vagabonds, and Sturdy Beggars: A New Gallery of Tudor and Early Stuart Rogue Literature edited by Arthur F. Kinney; 18 illusfrations by John Lawrence. 328 pp. $18.95, paper University of Massachusetts Press Reviewed by John Mucci. Mr. Mucci is Associate Editor of The Elizabethan Review. On the endless road of popular culture, there has always been a genre of entertainment which supposedly reveals the mysteries of the under world. Although whatever insight might be exposed, from the canting jargon to the details of a crime, accuracy seems to take a back seat to satisfying curiosity and a need for sensationalism. Today, there are interesting things to be leamed about ourselves by reading the pecuUar genre of EUzabethan pamphleteering known as rogue literature. Popular with all levels of literate society, these slender books purported to set down the manner by which con artists of all types might abscond with decent peoples' money and goods. Ostensibly written as a public service, to wam and arm society against rogues of all types, in their fascinating variety, they are an Elizabethan version of mob stories, with curious and lurid detail. This interest with the underworld and the seamiest side of life is one which has obvious parallels in modem times, particularly with readers who are most threatened by and distanced from such criminals. This so-caUed practical element of defending the populace against these all-too-prevalent creatures falls to second place against the pleasure ofreading about others who have been hoodwinked by them (and better still, hearing the details about rogues who have been caught in the act and punished). -

Picaresque Translation and the History of the Novel.Pdf

The Picaresque, Translation and the History of the Novel. José María Pérez Fernández University of Granada 1. Introduction The picaresque as a generic category originates in the Spanish Siglo de Oro, with the two novels that constitute the core of its canon—the anonymous Lazarillo de Tormes (1554) and Mateo Alemán’s Guzmán de Alfarache (1599, 1604). In spite of the fact that definitions of the picaresque are always established upon these Spanish foundations, it has come to be regarded as a transnational phenomenon which also spans different periods and raises important questions about the nature and definition of a literary genre. After its appearance in the Spanish 16th century, picaresque fiction soon spread all over Europe, exerting a particularly important influence during the 17th and 18th centuries in Germany, France and above all England, after which its impact diminished gradually. A study of the picaresque calls for a dynamic, flexible, and open-ended model. When talking about the picaresque we should not countenance it as a solid and coherent whole, but rather as a fluid set of features that had a series of precedents, an important foundational moment in the Spanish 16th and 17th centuries, and then spread out in a non-linear way. It grew instead into a complex web whose heterogeneous components were brought together by the fact that these new varieties of prose fiction were responding to similar cultural, social and economic realities. These new printed artefacts resulted from the demands of readers as consumers and the policies of publishers and printers as producers of marketable goods.