The Succession and Coronation of Magnus Erlingsson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anglo- Saxon England and the Norman Conquest, 1060-1066

1.1 Anglo- Saxon society Key topic 1: Anglo- Saxon England and 1.2 The last years of Edward the Confessor and the succession crisis the Norman Conquest, 1060-1066 1.3 The rival claimants for the throne 1.4 The Norman invasion The first key topic is focused on the final years of Anglo-Saxon England, covering its political, social and economic make-up, as well as the dramatic events of 1066. While the popular view is often of a barbarous Dark-Ages kingdom, students should recognise that in reality Anglo-Saxon England was prosperous and well governed. They should understand that society was characterised by a hierarchical system of government and they should appreciate the influence of the Church. They should also be aware that while Edward the Confessor was pious and respected, real power in the 1060s lay with the Godwin family and in particular Earl Harold of Wessex. Students should understand events leading up to the death of Edward the Confessor in 1066: Harold Godwinson’s succession as Earl of Wessex on his father’s death in 1053 inheriting the richest earldom in England; his embassy to Normandy and the claims of disputed Norman sources that he pledged allegiance to Duke William; his exiling of his brother Tostig, removing a rival to the throne. Harold’s powerful rival claimants – William of Normandy, Harald Hardrada and Edgar – and their motives should also be covered. Students should understand the range of causes of Harold’s eventual defeat, including the superior generalship of his opponent, Duke William of Normandy, the respective quality of the two armies and Harold’s own mistakes. -

Erkebiskopene Som Fredsskapere

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Erkebiskopene som fredsskapere i det norske samfunnet fra 1202 til 1263 Tore Sævrås Masteroppgave i historie Institutt for arkeologi, konservering og historie Universitetet i Oslo Høsten 2010 1 Forord Nå som jeg endelig er ferdig med min masteroppgave vil jeg rette en stor takk til min veileder Jon Vidar Sigurdsson, blant annet for gode råd, spørsmål og innspill som har gjort at jeg har greid å levere denne oppgaven innenfor nomerert tid. Særlig er jeg takknemelig for den tiden du satte av de siste ukene til gjennomlesning av kapittelutkastene til denne oppgaven, og at jeg når tid som helst kunne ringe deg dersom det var et eller annet jeg slet med i oppgaven min. Jeg har selv lært mye med å skrive denne oppgaven, og selv om det til tider har vært et slit, må jeg også innrømme at det har vært veldig morsomt å jobbe med denne oppgaven det siste semesteret da jeg begynte å se hvordan oppgaven kom til å se ut. Jeg vil også rette en takk til familie og venner for den forståelse og tålmodighet de har vist meg i de siste månedene, når jeg har arbeidet med å få ferdig denne oppgaven i tide. 2 Innholdsfortegnelse Innledning s. 4 Historiografi s. 5 Kilder s.10 1: Erkebiskopenes fredsskaperrolle i de store politiske konfliktene s.14 Initiativtakeren - erkebiskopen s.15 Initiativtakeren - de stridende partene s.17 Erkebiskopene som meglere s.23 Erkebiskopenes formidlerrolle s.27 Erkebiskopen som dommer s.33 Avslutning -

Viking Wirral and the Draken Harald Fairhair Viking Longship Project Liverpool Victoria Rowing Club, January 2012

Viking Wirral and the Draken Harald Fairhair Viking Longship Project Liverpool Victoria Rowing Club, January 2012 Stephen Harding The Draken Harald Fairhair Project 2009 - The Draken Harald Fairhair : aim to recreate a ship – the largest ever reconstruction with the superb seaworthiness that characterized the Viking age • Excellent sailing characteristics of ocean going ships • Warships usage of oars • “25 sesse” – 25 pairs of oars, 2 men to an oar • 35 metres long – half a football pitch – 8 metres wide Many reconstructed vessels have been based on the Gokstad (~AD850) at the Oslo Skiphuset The Viking , Chicago, 1893 – 2/3 replica crossed the Atlantic Odin’s Raven - Manx Millenium, 1979 Magnus Magnusson 1929-2007 The Gaia, late 1980’s – also crossed the Atlantic A recent project has also focused on a replica of the Oseberg ship (~AD800), also at the Skiphuset… ..Oseberg replica (2009) ..built by Per Bjørkum who wanted to show that the Oseberg ship was seaworthy! ..another was based on Skuldelev 2, a warship at Roskilde (dated to ~1050 and built in Dublin) ..reconstructed in 2004 as the “Sea Stallion” Photo Michael Borgen The Draken Harald Fairhair – largest ever reconstruction Thingwall – Þingvollr http://www.nottingham . ac. uk/- sczsteve/BBCRadio4_20May08.mp3 Tranmere - Tranmelr Vikinggg genes in Northern En gland pro ject Part 1 - Wirral and West Lancashire (2002-2007) Part 2 - North Lancashire, Cumbria and N. Yorkshire (2008- 2012) We have also been testing in Scandinavia Sigurd Aase, Haugesund … also Patron of the Draken project! Sigurd – and Marit Synnøve Vea: Project Leader Terje Andreassen: another Project Leader Turi, Mark, Marit, and Harald Løvvik Heading off to Karmøy Viking Village Harald Hårfagre – and Gyda Hafrsfjorden – site of the famous victoryyy by Harald Hårfagre June 2010: Sigurd agrees to the Draken coming to Wirral on its maiden voyage, 2013! Hjortspring Boat ~ 300BC - suggested reconstruction Nydam oak boat, Southern Jutland ~ 400 AD. -

Haroldswick: the Heart of Viking Unst

Trail 1: Haroldswick: The Heart of Viking Unst Haroldswick means Harold’s bay, named after Harald Fairhair who reputedly landed in this beautiful inlet. Today it is the ideal starting point for visitors curious about Viking Unst. 1 The Skidbladner 2 Longhouse replica Skidbladner is a full scale replica of the 9th century Gokstad ship The replica longhouse is based on the floorplan of found under a mound in Sandefjord, Norway. She is one of the one of the best preserved and excavated longhouse largest replica Viking longships ever built. Like all Viking ships she sites at Hamar. is clinker-built, i.e. made of long, overlapping planks which made Local craftsmen have had to rediscover Viking skills Unst Boat Haven longships fast and flexible, able to slip into rivers and voes, taking including cutting wooden joints. The stone and turf the Pictish residents by surprise. are Unst materials, the wood was imported from 3 Unst Boat Haven Scotland and the birchbark which “waterproofs” The Boat Haven contains more The Vikings invented the keel, the roof came from Norway. information about the Skidbladner and the rudder and the here you can also see how the Viking suncompass. Their longships clinker boat tradition has persisted in were a technological miracle, Shetland through to the present day. enabling the Vikings to conquer the seaways of the North 4 Unst Heritage Centre Atlantic. The Gokstad ship The centre includes exhibitions about past seated 32 oarsmen and carried and recent Unst life, including information up to 70 men. As they rowed, about the Vikings and various excavations the oarsmen sat on chests in Unst. -

Þingvellir National Park

World Heritage Scanned Nomination File Name: 1152.pdf UNESCO Region: EUROPE AND NORTH AMERICA __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Þingvellir National Park DATE OF INSCRIPTION: 7th July 2004 STATE PARTY: ICELAND CRITERIA: C (iii) (vi) CL DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Excerpt from the Report of the 28th Session of the World Heritage Committee Criterion (iii): The Althing and its hinterland, the Þingvellir National Park, represent, through the remains of the assembly ground, the booths for those who attended, and through landscape evidence of settlement extending back possibly to the time the assembly was established, a unique reflection of mediaeval Norse/Germanic culture and one that persisted in essence from its foundation in 980 AD until the 18th century. Criterion (vi): Pride in the strong association of the Althing to mediaeval Germanic/Norse governance, known through the 12th century Icelandic sagas, and reinforced during the fight for independence in the 19th century, have, together with the powerful natural setting of the assembly grounds, given the site iconic status as a shrine for the national. BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS Þingvellir (Thingvellir) is the National Park where the Althing - an open-air assembly, which represented the whole of Iceland - was established in 930 and continued to meet until 1798. Over two weeks a year, the assembly set laws - seen as a covenant between free men - and settled disputes. The Althing has deep historical and symbolic associations for the people of Iceland. Located on an active volcanic site, the property includes the Þingvellir National Park and the remains of the Althing itself: fragments of around 50 booths built of turf and stone. -

Genealogy in the Nordic Countries 2

Genealogy in The Nordic Countries 2 Finn Karlsen - Genealogy in Nordic Countries 23.09.2018 Presenter: 3 Finn Karlsen, Norway Retired consultant from the Regional State Archive in Trondheim 23.09.2018 4 Short history OF THE SCANDINAVIAN COUNTRIES Important years 5 1262 Iceland makes an agreement with Norway 1397 Kalmar Union between Danmark, Sweden and Norway with Iceland 1523 Kalmar union ends and Denmark, Norway and Iceland ruled by a common Danish King 1814 Norway gets its constitution, but ends up in union with Sweden 1905 Norway independent 1907 Iceland independent, but with Danish king 1944 Iceland total independence with President Border changes that might 6 influence our research Norway – Sweden Denmark – Sweden Denmark - Germany 7 Finn Karlsen - Genealogy in Nordic Countries 23.09.2018 8 Finn Karlsen - Genealogy in Nordic Countries 23.09.2018 9 Finn Karlsen - Genealogy in Nordic Countries 23.09.2018 10 Denmark Germany 1864 11 Prince-archives (Fyrstedømmenes arkiver) at National Archive in Copenhagen Ordinary archives like The church records at Landsarkivet in Aabenraa archives Some documents specially for the southern part of Slesvig are at the archive in Slesvig Finn Karlsen - Genealogy in Nordic Countries 23.09.2018 Early laws Norway: Frostating, Gulating and Eidsivating regional Laws 1274 King Magnus made common laws for Norway Laws Denmark: Jyske law, Skånske law and Sjællands law Iceland: 930 (written 1117) Graagaas 1264 Jarnsida 1281 Jonsbok Finn Karlsen - Genealogy in Nordic Countries 23.09.2018 12 13 -

The Hostages of the Northmen: from the Viking Age to the Middle Ages

Part IV: Legal Rights It has previously been mentioned how hostages as rituals during peace processes – which in the sources may be described with an ambivalence, or ambiguity – and how people could be used as social capital in different conflicts. It is therefore important to understand how the persons who became hostages were vauled and how their new collective – the new household – responded to its new members and what was crucial for his or her status and participation in the new setting. All this may be related to the legal rights and special privileges, such as the right to wear coat of arms, weapons, or other status symbols. Personal rights could be regu- lated by agreements: oral, written, or even implied. Rights could also be related to the nature of the agreement itself, what kind of peace process the hostage occurred in and the type of hostage. But being a hostage also meant that a person was subjected to restric- tions on freedom and mobility. What did such situations meant for the hostage-taking party? What were their privileges and obli- gations? To answer these questions, a point of departure will be Kosto’s definition of hostages in continental and Mediterranean cultures around during the period 400–1400, when hostages were a form of security for the behaviour of other people. Hostages and law The hostage had its special role in legal contexts that could be related to the discussion in the introduction of the relationship between religion and law. The views on this subject are divided How to cite this book chapter: Olsson, S. -

Birkebeiner Skifestival 2010

Birkebeiner Skifestival 2010 GENERALSPONSOR HOVEDSAMARBEIDSPARTNERE Statistikk Birkebeinerrennet 2010 Puljevis fordeling Birkebeinerrennet 2010 Påmeldt Start Prosent Fullført Merker Prosent SMK GMK SST KRUS GST FAT 25 MED 30 FAT 35 FAT 40 FAT 45 Storkrus Storkrus Påmeldt Start Prosent FullførtMerker Prosent SMK GMK SST KRUS GST FAT 25 MED 30 FAT 35 FAT 40 FAT 45 Storkrus Storkrus sølv- gull- sølv- gull- medalje medalje medalje medalje FIS Marathon Women13 12 92,3 12 12 100,0 4 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Pulje 1 476 462 97,1 459 456 98,7 36 28 11 9 3 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 FIS Marathon Men 54 51 94,4 50 50 98,0 14 2 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Pulje 2 516 501 97,1 494 481 96,0 85 25 13 4 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 Kvinner 16-17 år 48 48 100,0 44 30 62,5 27 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Pulje 3 379 361 95,3 351 321 88,9 66 15 4 2 3 3 4 0 0 0 0 0 Kvinner 18-19 år 66 63 95,5 63 34 54,0 9 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Pulje 4 517 491 95,0 482 410 83,5 113 22 6 4 1 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 Kvinner 20-24 år 203 192 94,6 182 46 24,0 18 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Pulje 5 480 462 96,3 451 318 68,8 96 10 4 3 1 2 1 1 0 0 0 0 Kvinner 25-29 år 436 408 93,6 394 85 20,8 50 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Pulje 6 485 458 94,4 450 217 47,4 93 9 2 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 Kvinner 30-34 år 320 288 90,0 281 63 21,9 29 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Pulje 7 467 443 94,9 434 138 31,2 76 4 4 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Kvinner 35-39 år 371 331 89,2 315 78 23,6 18 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Pulje 8 484 460 95,0 454 97 21,1 47 2 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 Kvinner 40-44 år 475 431 90,7 417 138 32,0 33 11 4 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Pulje 9 666 629 94,4 614 92 14,6 25 4 3 0 0 0 0 0 -

Royal Ideology in Fagrskinna

Háskóli Íslands Íslensku- og Menningardeild Medieval Icelandic Studies Royal Ideology in Fagrskinna A Case Study of Magnús inn blindi. Ritgerð til M.A.-prófs Joshua Wright Kt.: 270194-3629 Leiðbeinandi: Sverrir Jakobsson May 2018 Acknowledgements I owe thanks to too many people to list, but I would be remiss if I did not mention Julian Valle, who encouraged and advised me throughout the process, and Jaka Cuk for his company and council at numerous late night meetings. Dr. Sverrir Jakobsson’s supervision and help from Dr. Torfi H. Tulinius were both indispensable help throughout the process. I owe my wife, Simone, a special thanks for her input, and an apology for keeping her up in our small room as I worked at strange hours. I cannot fully express my debt to my father, David Wright, and my uncle Harold Lambdin, whose urging and encouragement pushed me to try academia in the first place. I dedicate this to my mother, Susanne, who would have loved to see it. ii Abstract: When looking at the political thought of the kings’ sagas, scholarship has overwhelmingly focused on Heimskringla, widely regarded as the most well-written compilation, or on the older Morkinskinna because it is more proximal to the ‘original’ sources. An intermediate source, Fagrskinna, is almost always overlooked, mentioned only in passing by scholars that are more interested in other texts. The limited work that has been done on this source, most prominently by Gustav Indrebø, attracts little attention and Indrebø has remained mostly unchallenged nearly a century after his writing. While there have been systemic analyses of the ideology of these sagas (by Bagge and Ármann Jakobsson, among others) they are only tangentially interested in Fagrskinna, with the result that this work and its unique ideology have been largely unexplored, although its subject matter predisposes it towards contributing to the discussion. -

Saxo and His Younger Cousin a Study in the Principles Used to Make Gesta Danorum Into Compendium Saxonis

Saxo and his younger cousin a study in the principles used to make Gesta Danorum into Compendium Saxonis Marko Vitas Supervisor: Arne Jönsson Centre for Language and Literature, Lund University MA in Language and Linguistics, Latin SPVR01 Language and Linguistics: Degree Project – Master's (First Year) Thesis, 15 credits January 2017 Abstract Saxo and his younger cousin a study in the principles used to make Gesta Danorum into Compendium Saxonis The aim of this study is to offer as detailed analysis as possible of the Compendium Saxonis, a late medieval abridgement of the famous historical work Gesta Danorum, written towards the end of the XII century by Saxo Grammaticus. Books I–IV and XVI have been used for this purpose. The study contains an introduction, two chapters and a conclusion. In the introduction, scarce information known about life of Saxo Grammaticus, author of the original work, is summarized and briefly discussed. Further on, general information about Compendium and its dating are referred to. Second part of the introduction deals with the theoretical background concerning ancient and medieval abridged version. In this discussion, we rely on Paul Grice’s Theory of Communication and its reinterpretation by Markus Dubischar. In the First chapter, called Treatment of the content of Gesta Danorum in the Compendium Saxonis we analyse the way the author of the shorter version dealt with the content of the original. Particular attention is payed to the abridgment’s treatment of four distinct episode types frequent in the original. These are episodes pertaining to the supernatural, episodes pertaining to the moral and didactical issues, episodes pertaining to the upbringing, legal activity and death of a Danish king and episodes pertaining to war and destruction. -

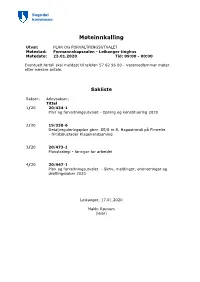

Møteinnkalling

Sogndal kommune Møteinnkalling Utval: PLAN OG FORVALTNINGSUTVALET Møtestad: Formannskapssalen - Leikanger tinghus Møtedato: 23.01.2020 Tid: 09:00 - 00:00 Eventuelt forfall skal meldast til telefon 57 62 96 00 - Varamedlemmar møter etter nærare avtale. Sakliste Saksnr. Arkivsaksnr. Tittel 1/20 20/434-1 Plan og forvaltningsutvalet - Opning og konstituering 2020 2/20 19/338-6 Detaljreguleringsplan gbnr. 85/8 m.fl. Hagastrondi på Fimreite - fritidsbustader Klagehandsaming 3/20 20/473-1 Planstrategi - føringar for arbeidet 4/20 20/447-1 Plan og forvaltningsutvalet - Skriv, meldingar, orienteringar og drøftingssaker 2020 Leikanger, 17.01.2020 Malén Røysum (leiar) Sogndal kommune Sak 1/20 Plan og forvaltningsutvalet Saksh.: Maj Britt Brendstuen Arkiv: Arkivsak: 20/434 Saksnr.: Utval Møtedato 1/20 Plan og forvaltningsutvalet 23.01.2020 Sak 1/20 Plan og forvaltningsutvalet - Opning og konstituering 2020 Punkt 1. Opning A. Konstituering av møte: Møtet lovleg sett med følgjande til stades: Malèn Røysum, Arne Glenn Flåten, Bodil Merete Andersen Strand, Ivar Slinde, Lars Trygve Sæle, Magne Bruland Selseng, Rita Navarsete, Stig Ove Ølmheim og Oddbjørn Bukve Frå administrasjon møter kommunalsjef Arne Abrahamsen og politisk sekretær Marit Silje Husabø Innkalling og saksliste - godkjenning Møteleiar: Malén Røysum Ope møte Framlegg: Malén Røysum, Bodil Merete Andersen Strand og Magne Bruland Selseng får fullmakt til å signere protokollen Side 2 av 11 Sogndal kommune Sak 2/20 Plan og forvaltningsutvalet Saksh.: Hilde Helene Bjørnstad Arkiv: Arkivsak: 19/338 Saksnr.: Utval Møtedato 2/20 Plan og forvaltningsutvalet 23.01.2020 Sak 2/20 Detaljreguleringsplan gbnr. 85/8 m.fl. Hagastrondi på Fimreite - fritidsbustader Klagehandsaming Tilråding: Forvaltningsutvalet tek klagar på detaljreguleringsplan for Hagastrondi på Fimreite – Fritidsbustader delvis til følgje, i samsvar med tilrådinga frå rådmann. -

European Revivals from Dreams of a Nation to Places of Transnational Exchange

European Revivals From Dreams of a Nation to Places of Transnational Exchange EUROPEAN REVIVALS From Dreams of a Nation to Places of Transnational Exchange FNG Research 1/2020 Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Illustration for the novel, Seven Brothers, by Aleksis Kivi, 1907, watercolour and pencil, 23.5cm x 31.5cm. Ahlström Collection, Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum Photo: Finnish National Gallery / Hannu Aaltonen European Revivals From Dreams of a Nation to Places of Transnational Exchange European Revivals From Dreams of a Nation to Places of Transnational Exchange European Revivals. From Dreams of a Nation to Places of Transnational Exchange FNG Research 1/2020 Publisher Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki Editors-in-Chief Anna-Maria von Bonsdorff and Riitta Ojanperä Editor Hanna-Leena Paloposki Language Revision Gill Crabbe Graphic Design Lagarto / Jaana Jäntti and Arto Tenkanen Printing Nord Print Oy, Helsinki, 2020 Copyright Authors and the Finnish National Gallery Web magazine and web publication https://research.fng.fi/ ISBN 978-952-7371-08-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-7371-09-1 (pdf) ISSN 2343-0850 (FNG Research) Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................. vii ANNA-MARIA VON BONSDORFF AND RIITTA OJANPERÄ VISIONS OF IDENTITY, DREAMS OF A NATION Ossian, Kalevala and Visual Art: a Scottish Perspective ........................... 3 MURDO MACDONALD Nationality and Community in Norwegian Art Criticism around 1900 .................................................. 23 TORE KIRKHOLT Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity: Three Key Images in Focus ...................................................................... 49 FRANCES FOWLE Listening to the Voices: Joan of Arc as a Spirit-Medium in the Celtic Revival .............................. 65 MICHELLE FOOT ARTISTS’ PLACES, LOCATION AND MEANING Inventing Folk Art: Artists’ Colonies in Eastern Europe and their Legacy .............................