An Equal Burden: the Men of the Royal Army Medical Corps in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compassion and Courage

Compassion and courage Australian doctors and dentists in the Great War Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne War has long brought about great change and discovery in medicine and dentistry, due mainly to necessity and the urgency and severity of the injuries, disease and other hardships confronting patients and practitioners. Much of this innovation has taken place in the field, in makeshift hospitals, under conditions of poor Compassion hygiene and with inadequate equipment and supplies. During World War I, servicemen lived in appalling conditions in the trenches and were and subjected to the effects of horrific new weapons courage such as mustard gas. Doctors and dentists fought a courageous battle against the havoc caused by AUSTRALIAN DOCTORS AND DENTISTS war wounds, poor sanitation and disease. IN THE REAT AR Compassion and courage: Australian doctors G W and dentists in the Great War explores the physical injury, disease, chemical warfare and psychological trauma of World War I, the personnel involved and the resulting medical and dental breakthroughs. The book and exhibition draw upon the museums, archives and library of the University of Melbourne, as well as public and private collections in Australia and internationally, Edited by and bring together the research of historians, doctors, dentists, curators and other experts. Jacqueline Healy Front cover (left to right): Lafayette-Sarony, Sir James Barrett, 1919; cat. 247: Yvonne Rosetti, Captain Arthur Poole Lawrence, 1919; cat. 43: [Algernon] Darge, Dr Gordon Clunes McKay Mathison, 1914. Medical History Museum Back cover: cat. 19: Memorial plaque for Captain Melville Rule Hughes, 1922. University of Melbourne Inside front cover: cat. -

Number of Soldiers That Joined the Army from Registered Address in Scotland for Financial Years 2014 to 2017

Army Secretariat Army Headquarters IDL 24 Blenheim Building Marlborough Lines Andover Hampshire, SP11 8HJ United Kingdom Ref: FOI2017/10087/13/04/79464 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.army.mod.uk XXX XXXXXXXXXXX 5 December 2017 XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Dear XXXXXX, Thank you for your email of 14 October in which you clarified your request of 6 October to the following : ‘In particular please clarify what you mean by ‘people from Scotland’. Are you seeking information regarding individuals who identify themselves as being Scottish regardless of where they live now, or people who currently have a Scottish address regardless of their background or country of origin? Please note that for the MOD Joint Personnel Administration, some of the nationality options an individual can record themselves as include ‘British’, ‘Scottish’ or ‘British Scottish’. I was mainly looking for those having joined the Army from a Scottish address as I’m looking at how many people located in Scotland join the Army. Further clarification is required concerning the second part of your request - please clarify if you want Corps and Infantry Regiment (In essence Cap badge) or Corps and Infantry totals. Please note that a proportion of those who joined the untrained strength in 2016 may still be in training. Yes please, looking for Cap Badge of entrants from Scotland should this information exist. Finally please confirm that you require the information for both parts of your request by Financial Years 2014, 2015 & 2016. Yes please, If the information exists for each year then I would be grateful for this. If this is significantly time consuming then 2016 would be sufficient.’ I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 2000. -

Royal Army Medical Corps

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-22-02-21 on 1 February 1914. Downloaded from JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS. <torps mews. FEBRUARY, 1914. HONOURS. The King has been graciously pleased to confer the honour of Knighthood upon Protected by copyright. Surgeon-General Arthur Thomas Sloggett, C.B., C.M.G., K.H.S., Director Medical Services in India. The King has been graciously pleased to give orders for the following appointment to the Most Honourable Order of the Bath: To be Ordinary Member of the Military Division, or Companion of the said Most Honourable Order: Surgeon;General Harold George Hathaway, Deputy Director of Medical Services, India. ESTABLISHMENTS. Royal Hospital, Chelsea: Lieutenant-Colonel George A. T. Bray, Royal Army Medical Corps, to be Deputy Surgeon, vice Lieutimant-Colonel H. E. Winter, who has vacated the appointment, dated January 20, 1914. ARMY MEDICAL SERYICE. Surgeon-General Owen E. P. Lloyd, V.C., C.B., is placed on retired pay, dated January 1, 1914. Colonel Waiter G. A. Bedford, C.M.G., to be Surgeon-General, vice O. E. P. Lloyd, V.C., C.B., dated January 1, 19]4. http://militaryhealth.bmj.com/ Colonel Alexander F. Russell, C.M.G., M.B., is placed on retired pay, dated December 21, 1913. Colonel Thomas J. R. Lucas, C.B., M.B., on completion of four years' service in his rank, retires on retired pay. dated January 2, 1914. Colonel Robert Porter, M.B., on completion of four years' service in his rank, is placed on the half-pay list, dated January 14, 1914. -

Royal Army Medical Corps

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-16-01-16 on 1 January 1911. Downloaded from JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS. (torps 1Rews. JANUARY, 1911. ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS. The King has been pleased to give and grant unto Captain Howard Ensor, D.S.O., Royal Army Medical Corps, His Majesty's Royal licence and authority to accept and Protected by copyright. wear the Imperial Ottoman Order of the Osmanieh, Fourth Class, which has been conferred upon him by His Highness the Khedive of Egypt; authorised by His Imperial Majesty the Sultan of Turkey, in recognition of valuable services rendered by him. REGULAR FORCES. ESTABLISHMENTS. Royal Army Medical Corps School of Instruction.-Major Claude K. Morgan, M.B. R.A.M.C., to be an Instructor, vice Major C. C. Fleming, D.S.O., who has vacated that appointment. Dated October 29, 1910. CAVALRY. 1st Life Guards.-Surgeon·Captain Alfred C. Lupton, M.B., is placed temporarily on the half-pay list on accoun't of ill-health. Dated November, 22, 1910. ARMY MEDICAL SERVICE. Royal Army Medical Corps.-The undermentioned officers, from the seconded list, are restored to the Establishment, dated November 18, 1910 :-Captain William M. B. http://militaryhealth.bmj.com/ Sparkes. Lieutenant Harold T. Treves. Captain Edward Gibbon, M.B., is seconded for service with the Egyptian Army. Dated November 13, 1910. ARRIVALS HOME FOR DUTY.-From India: On November 24, Lieutenant Colonel T. B. Winter; Captains C. H. Turner, J. P. Lynch, and E. G. R. Lithgow. From Straits Settlements: On November 29, Major I. -

Royal Army Medical Corps

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-07-01-23 on 1 July 1906. Downloaded from JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS. (torp£; 'lRew£;. JULY, 1906. Protected by copyright. ARMY MEDICAL SERYICE.-GAZETTE NOTIFICATIONS. Lieutenant-Colonel James M. Irwin, lVLB., Royal Army Medical Corps, to be Assistant Director-General, vice Lieutenant-Colonel W. Babtie, V.O., O.M_G., M.B., Royal Army Medical Corps, whose tenure of that appointment has expired, dated June 1, 1906. ROYAL ARMY ME DICAL CORPS. The undermentioned Lieutenants to be Captains, dated March 1, 1906: Arthur B. Smallman, M.B., Went worth F. Tyndale, C.M.G., M.B.. Percival Davidson, D.S.O., M.B., William F. Ellis, John McKenzie, M.B., Norman D. Walker, M.B., Arthur H. Hayes, Henry J. Crossley, Ralph B. Ainsworth, Charles A. J. A. Balck, M.B., Reginald Storrs, Raymond L. V. Foster, 1ILB., Frederick A. H. Olarke, George A. K. H. Reed, John W. S. Seccombe, John 11£' H. Conway, Sydney M. W. Meadows, Herbert V. Bagshawe, DudleyS. Skelton, Oharles V. B. Stanley, M.D., Hugh G. S. Webb, William http://militaryhealth.bmj.com/ W. Browne, Richard Rutherford, lILB., William D. ·C. Kelly, lILB., Norman E. J. Harding, M.B., Robert J. Franklin. Lieutenant Leonard Bousfield, lILB., is seconded for service with the Egyptian Army, dated April 30, 1906. Lieutenant Francis liT. IiI. Ommanney, from the seconded list, to be ·Lieutenant, dated May 14, 1906. Lieutenant Cuthbert G. Browne, from the seconded list, to be Lieutenant, dated June 1, 1906. Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas H. -

Supplement to the London Gazette, 13 December, 1945 6059

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 13 DECEMBER, 1945 6059 Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Graham Alexander Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Alfred John ODLING- NORRIS (122649), Royal Electrical and Mechanical . SMEE (34483). The Royal Sussex Regiment (Kings- Engineers. boidge). Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) John O'DWYER Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Bernard Basil SMITH (31586), Corps of Royal Engineers (Newcastle-on- (47140), Corps of Royal Engineers. Tyne). Lieutenant Colonel Eric Bindloss SMITH (18074), Colonel (acting) Oswald James Ritchie OKR (31587), Royal Regiment of Artillery (Wantage). Corps of Royal Engineers (Sittingboume). Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) John Stuart Pope Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Sidney Walter OWEN SMITH (114966), Pioneer Coups (Leeds). (193970), Royal Army Ordnance Corps (Brighton Lieutenant Colonel (acting) Francis Joseph SODEN 6)- (133827), Royal Army Service Corps (E.F.I.).' Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Lionel Alfred Brading (Hinchley Wood, Surrey). PATEN (23680), Corps of Royal Engineers (Peter- Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Archibald Richard borough). Charles SOUTHBY (50234), The Rifle Brigade Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Gordon Oliver (Prince Consort's Own) (Andover). PEAKE (111907), Royal Army Service Corps (Wey- Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) James Eustace. bridge). SPEDDING (26887), Royal Regiment of Artillery Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Herbert Stanley (Keswick). PEARCE (59620), Pioneer Corps. The Reverend George Archibald Douglas SPENCE, Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Ralph Whitin PETERS M.C. (3422), Chaplain to the Forces, Second Class, (LA. 389), Indian Armoured Corps. New Zealand Military Forces. Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) John PETTIGREW Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Charles Richard (89927), Corps of Royal Engineers (Edinburgh). SPENCER (49923), i2th Royal Lancers (Prince of Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Robert Thomas Wales's), Koyal Armoured Corps (Yelverton). PRIEST, M.B.E. (39354), Royal Regiment of Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) Henry Sydney Oh'ver Artillery. -

Supplement to the London Gazette, 9Th May 1995 O.B.E

6612 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 9TH MAY 1995 O.B.E. in Despatches, Commended for Bravery or Commended for Valuable Service in recognition of gallant and distinguished services To be Ordinary Officers of the Military Division of the said Most in the former Republic of Yugoslavia during the period May to Excellent Order: November 1994: Lieutenant Colonel David Robin BURNS, M.B.E. (500341), Corps of Royal Engineers. Lieutenant Colonel (now Acting Colonel) James Averell DANIELL (487268), The Royal Green Jackets. ARMY Mention in Despatches M.B.E. To be Ordinary Members of the Military Division of the said Most Major Nicholas George BORWELL (504429), The Duke of Excellent Order: Wellington's Regiment. Major Duncan Scott BRUCE (509494), The Duke of Wellington's 2464S210 Corporal Stephen LISTER, The Royal Logistic Corps. Regiment. The Reverend Duncan James Morrison POLLOCK, Q.G.M., 24631429 Sergeant Sean CAINE, The Duke of Wellington's Chaplain to , the Forces 3rd Class (497489), Royal Army Regiment. Chaplains' Department. 24764103 Lance Corporal Carl CHAMBERS, The Duke of 24349345 Warrant Officer Class I (now Acting Captain) Ian Wellington's Regiment. SINCLAIR, Corps of Royal Engineers. 24748686 Lance Corporal (now Acting Corporal) Neil Robert 24682621 Corporal (now Sergeant) Nigel Edwin TULLY, Corps of FARRELL, Royal Army Medical Corps. Royal Engineers. Lieutenant Colonel (now Acting Colonel) John Chalmers McCoLL, Major Alasdair John Campbell WILD (514042), The Royal O.B.E., (495202), The Royal Anglian Regiment. Anglian Regiment. 24852063 Private (now Lance Corporal) Liam Patrick SEVIOUR, The Duke of Wellington's Regiment. ROYAL AIR FORCE O.B.E. Queen's Commendation for Bravery To be an Ordinary Officer of the Military Division of the said Most Excellent Order: 24652732 Corporal Mark David HUGHES, The Duke of Wing Commander (now Group Captain) Andrew David SWEETMAN Wellington's Regiment. -

Dentistry and the British Army: 1661 to 1921

Military dentistry GENErAL Dentistry and the British Army: 1661 to 1921 Quentin Anderson1 Key points Provides an overview of dentistry in Britain and Provides an overview of the concerns of the dental Illustrates some of the measures taken to provide its relation to the British Army from 1661 to 1921. profession over the lack of dedicated dental dental care to the Army in the twentieth century provision for the Army from the latter half of the before 1921 and the formation of the Army nineteenth century. Dental Corps. Abstract Between 1661 and 1921, Britain witnessed signifcant changes in the prevalence of dental caries and its treatment. This period saw the formation of the standing British Army and its changing oral health needs. This paper seeks to identify these changes in the Army and its dental needs, and place them in the context of the changing disease prevalence and dental advances of the time. The rapidly changing military and oral health landscapes of the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century bring recognition of the Army’s growing dental problems. It is not, however, without years of campaigning by members of the profession, huge dental morbidity rates on campaign and the outbreak of a global confict that the War Ofce resource a solution. This culminates in 1921 with, for the frst time in 260 years, the establishment of a professional Corps within the Army for the dental care of its soldiers; the Army Dental Corps is formed. Introduction Seventeenth century site; caries at contact areas was rare. In the seventeenth century, however, the overall This paper sets out to illustrate the links At the Restoration in 1660, Britain had three prevalence increased, including the frequency between dentistry and the British Army over armies:1 the Army raised by Charles II in of lesions at contact areas and in occlusal the 260 years between the Royal Warrant exile, the Dunkirk garrison and the main fssures.3 In contrast, it is suggested by Kerr of Charles II establishing today’s Army Commonwealth army. -

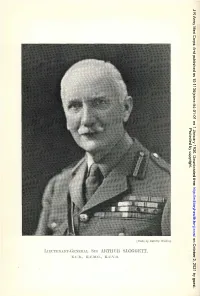

Lmc'renakt-Geciehal SIR Artiluh SLOGGETT, K .N.B., K.C.1-J.G., K.E.V.O

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-54-01-01 on 1 January 1930. Downloaded from Protected by copyright. http://militaryhealth.bmj.com/ on October 2, 2021 by guest. [Photo hy Dorcth?/ WtldiJlg LmC'rENAKT-GECiEHAL SIR ARTIlUH SLOGGETT, K .n.B., K.C.1-J.G., K.e.v.o. J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-54-01-01 on 1 January 1930. Downloaded from VOL. LIV. JANUARY, 1930. No. 1. Authors are alone responsible for the statements made and the opinions expressed in their papers. ~tlurnal of tb' ~bituar\? LIEUTENANT-GENERAL SIR ARTHUR SLOGGETT, K.C.B., Protected by copyright. K.C.M.G., K.C.V.O. SIR ARl'HUR SLOGGEl'l' was the son of Inspector-General W. H. Sloggett, R.N., and was born at Stoke Damerel, Devon, on November 24, 1857. He was educated' at King's College, London, of which he was subsequently elected a Fellow. He obtained the M.R.C.S.England and L.R.C.P.Edinburgh in 1880, and on February 5, 1881, was commissioned as Surgeon in the Medical Staff. In his batch were several men who afterwards attained distinction as administrators, the most eminent among them being the late Sir William Babtie. Sir Arthur Sloggett will be chiefly remembered as a wise administrator, his savoir-faire, knowledge of the world and of men, enabled him to succeed where other men, though http://militaryhealth.bmj.com/ well versed in Regulations, would have failed. Sir Arthur saw much active service ana was senior medical officer with British troops in' the Dongola expedition, 1896; he was mentioned in dispatches, received the Egyptian medal with two clasps, the Order of the Osmanieh and was promoted Surgeon Lieutenant-Colonel. -

Raising Professional Confidence: the Influence of the Anglo-Boer War (1899 – 1902) on the Development and Recognition of Nursing As a Profession

Raising professional confidence: The influence of the Anglo-Boer War (1899 – 1902) on the development and recognition of nursing as a profession A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing in the Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences. 2013 Charlotte Dale School of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work 2 Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 Declaration ........................................................................................................................................................... 6 Copyright Statement ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................................... 8 The Author ............................................................................................................................................................ 9 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 10 Chapter One ........................................................................................................................................................ 17 Nursing, War and the late Nineteenth Century -

Newfoundland at Gallipoli

Canadian Military History Volume 27 Issue 1 Article 18 2018 The Forgotten Campaign: Newfoundland at Gallipoli Tim Cook Mark Osborne Humphries Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Cook, Tim and Humphries, Mark Osborne "The Forgotten Campaign: Newfoundland at Gallipoli." Canadian Military History 27, 1 (2018) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cook and Humphries: The Forgotten Campaign The Forgotten Campaign Newfoundland at Gallipoli TIM COOK & MARK OSBORNE HUMPHRIES Abstract : Gallipoli has no place in the collective memory of most Canadians and even among Newfoundlanders, Gallipoli has not garnered as much attention as the ill-fated attack at Beaumont Hamel. Although largely forgotten, Newfoundland’s expedition to Gallipoli was an important moment in the island’s history, one that helped shape the wartime identity of Newfoundlanders. Like other British Dominions, Newfoundland was linked to the Empire’s world-wide war experience and shared in aspects of that collective imperial identity, although that identity was refracted through a local lens shaped by the island’s unique history. Gallipoli was a brutal baptism of fire which challenged and confirmed popular assumptions about the Great War and laid the foundation of the island’s war mythology. This myth emphasized values of loyalty, sacrifice, and fidelity, affirming rather than reducing the island’s connection to Mother Britain, as was the case in the other Dominions. -

Under What Circumstances Would You Agree to Go to War?

TOPIC 5.1 What are some of the costs of war? Under what circumstances would you agree to go to war? 5.1 5.2 A regiment takes shape Recruits at Headquarters in St. John’s, 1914 5.3 “D” Company departs Men of the Newfoundland Regiment leave St. John’s onboard the SS Stephano, March 20, 1915. “D” Company joined “A,” “B,” and “C” Companies guarding Edinburgh Castle on March 30, 1915, bringing the regiment to full battalion strength. 5.4 A Newfoundland Regiment pin 400 This painting entitled We Filled ‘Em To The Gunnells by Sheila Hollander shows what life possibly may have been like in XXX circa XXX. Fig. 3.4 5.5 The Forestry Corps Approximately 500 men enlisted in the Newfoundland Forestry Corps and worked at logging camps in Scotland during 1917 and 1918. Forestry Corps pin shown above. Dealing with the War When Great Britain declared war on Germany on October 3, 1914, the soldiers marched from their training August 4, 1914, the entire British Empire was brought camp to board the SS Florizel, a steamer converted into a into the conflict. This included Newfoundland. For troopship, which would take them overseas. Newfoundland, therefore, the decision was not whether to enter the war, but how, and to what degree its people Under the NPA’s direction, volunteers continued to be would become involved. recruited, trained, equipped, and shipped to Europe until a Department of Militia was formed by the National The government of Edward Morris quickly decided Government in July 1917. In addition to the many men to raise and equip a regiment for service in Europe.