Interview No. SAS4.02.02 Jimmy Wells Interviewer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

University of Maryland Commencement May 22, 2020

University of Maryland Commencemenmay 22, 2020 Table of Contents CONGRATULATIONS BACHELOR’S DEGREES From the President 1 Agriculture and Natural Resources, From the Alumni Association President 2 College of 24 Architecture, Planning and SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES Preservation, School of 25 Graduating Student Speaker 4 Arts and Humanities, College of 25 University Medalists 5 Behavioral and Social Sciences, Honorary Degree Recipients 7 College of 29 Commencement Speaker 9 Business, Robert H. Smith School of 35 Computer, Mathematical, and DOCTORAL DEGREES 10 Natural Sciences, College of 42 Education, College of 48 MASTER’S DEGREES 15 Engineering, A. James Clark School of 49 Graduate Certificates 22 Information Studies, College of 52 Journalism, Philip Merrill College of 53 Public Health, School of 54 Public Policy, School of 56 THE “DO GOOD” CAMPUS Undergraduate Studies 56 Certificate Programs 56 The University of Maryland commits to becoming HONORS COLLEGE, CITATION AND a global leader in advancing social innovation, NOTATION PROGRAMS, AND ACADEMIC AND SPECIAL AWARDS philanthropy and nonprofit leadership with its Do Honors College 57 Good Campus. CIVICUS 59 College Park Scholars 59 Beyond the Classroom 62 Our Do Good Campus effort amplifies the power of Federal Fellows 62 Terps as agents of social innovation and supports First-Year Innovation and Research Experience 62 the university’s mission of service. We’re working to Global Communities 63 ensure all University of Maryland students graduate Global Fellows 63 equipped and motivated to do good in their careers, Hinman CEOs 63 Immigration and Migration Studies 63 their communities and the world. Jiménez-Porter Writers’ House 63 Language House 63 Ronald E. -

Arts Maryland

ARTS MARYLAND To view online, go to: http://www.emarketingmd.org/Tourism/MSAC/Newsletter/January_10/Index.html PROGRAMS EVENTS GRANTS ARTS MARYLAND Latino Arts Roundtable JANUARY 2010 MSAC convenes session for Latino arts community Support the arts at Maryland Arts Day New policy allows TEP funding for public art Nine Md. organizations receive NEA awards MSAC convenes session for growing Latino arts community Local performers garner Participants included (l to r): Carolyn Comacho, Montgomery County Grammy nominations Public Schools; Olga Diaz, St. Michael and St. Patrick’s Church; Ted Resources available David, La Layenda; Susanna Nemes, Maryland State Arts Councilor; for artists, arts groups and Rosalina Delgado, Hispanic Business Federation. Polisar fans bring Having worked with Maryland’s Latino community in recent months, the Maryland new twists to old songs State Arts Council (MSAC) hosted its first Latino Arts Roundtable, Jan. 12, to discuss grant opportunities and how to best serve that community. The event was held at the Arts Council’s office, 175 W. Ostend St. in South Baltimore. “Historically, the Arts Council has been a leader among state arts agencies in gaining a broad and diverse constituency,” said Gov. Martin O’Malley. “We intend to continue that leadership by convening Latino leaders and artists in order to extend our grant programs into Maryland’s growing Latino community.” One of the goals of the Arts Council’s strategic plan, Imagine Maryland, is to recognize the state’s cultural diversity and forge connections with diverse communities. http://www.emarketingmd.org/Tourism/MSAC/Newsletter/January_10/Index.html (1 of 5)1/26/2012 2:10:24 PM ARTS MARYLAND Support the arts at Maryland Arts Day Hundreds of arts advocates are expected to meet with state legislators in Annapolis, Feb. -

The Jazz Record

oCtober 2019—ISSUe 210 YO Ur Free GUide TO tHe NYC JaZZ sCene nyCJaZZreCord.Com BLAKEYART INDESTRUCTIBLE LEGACY david andrew akira DR. billy torn lamb sakata taylor on tHe Cover ART BLAKEY A INDESTRUCTIBLE LEGACY L A N N by russ musto A H I G I A N The final set of this year’s Charlie Parker Jazz Festival and rhythmic vitality of bebop, took on a gospel-tinged and former band pianist Walter Davis, Jr. With the was by Carl Allen’s Art Blakey Centennial Project, playing melodicism buoyed by polyrhythmic drumming, giving replacement of Hardman by Russian trumpeter Valery songs from the Jazz Messengers songbook. Allen recalls, the music a more accessible sound that was dubbed Ponomarev and the addition of alto saxophonist Bobby “It was an honor to present the project at the festival. For hardbop, a name that would be used to describe the Watson to the band, Blakey once again had a stable me it was very fitting because Charlie Parker changed the Jazz Messengers style throughout its long existence. unit, replenishing his spirit, as can be heard on the direction of jazz as we know it and Art Blakey changed By 1955, following a slew of trio recordings as a album Gypsy Folk Tales. The drummer was soon touring my conceptual approach to playing music and leading a sideman with the day’s most inventive players, Blakey regularly again, feeling his oats, as reflected in the titles band. They were both trailblazers…Art represented in had taken over leadership of the band with Dorham, of his next records, In My Prime and Album of the Year. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

Parking Lot Crisis Near

Xavier University Exhibit All Xavier Student Newspapers Xavier Student Newspapers 1964-10-02 Xavier University Newswire Xavier University (Cincinnati, Ohio) Follow this and additional works at: https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/student_newspaper Recommended Citation Xavier University (Cincinnati, Ohio), "Xavier University Newswire" (1964). All Xavier Student Newspapers. 2170. https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/student_newspaper/2170 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Xavier Student Newspapers at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Xavier Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Xavier University Library a vier ems Vol. XLIX. CINCINNATI, OHIO, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 2, 1964 TEN CENTS No. 2. PARKING LOT CRISIS NEAR W ork111en, Dornt Ilr.llalllelllies 'Vill Gobble Up Student Space Former Pro[ Was Psych DearlnJeut Dean Asks For Patience \\'hen Pro.iect Beg·ins Cl:nair111au In Tibbles Nov. 1 Requiem High Mass for Dr. "The parking situation will get Ignatius Hamel, 73, 4354. West worse before it can get better." Eighth St., Price Hill, former With this statement, Rev. Patrick cliait·man of the Xaviet· Univer H. Ratterman, S.J., Dean o[ Men, sity psychology department and succintly summed up the plight dil'ector of the guidance depart of the driving Xavier student. He ment, was intoned Thursday at further staled that "During the 9:30 a.m., at St. William Church, present academic year, because Pl'ice Hill. of the construction on campus Dr. Hamel died Monday after which brings hundreds oC con a brief illness in St. -

22Nd Day 433

HOUSE JOURNAL EIGHTY-FIFTH LEGISLATURE, REGULAR SESSION PROCEEDINGS TWENTY-SECOND DAY Ð THURSDAY, FEBRUARYi23, 2017 The house met at 10:06 a.m. and was called to order by the speaker. The roll of the house was called and a quorum was announced present (Recordi41). Present Ð Mr. Speaker(C); Allen; Alonzo; Alvarado; Anchia; Anderson, C.; Anderson, R.; AreÂvalo; Ashby; Bailes; Bell; Bernal; Biedermann; Blanco; Bohac; Bonnen, D.; Bonnen, G.; Burkett; Burns; Burrows; Button; Cain; Canales; Capriglione; Clardy; Coleman; Collier; Cook; Cortez; Cosper; Craddick; Cyrier; Dale; Darby; Davis, S.; Davis, Y.; Dean; Dutton; Elkins; Faircloth; Fallon; Flynn; Frank; Frullo; Geren; Giddings; Goldman; Gonzales; GonzaÂlez; Gooden; Guerra; Guillen; Gutierrez; Hefner; Hernandez; Herrero; Hinojosa; Holland; Howard; Huberty; Hunter; Isaac; Israel; Johnson, E.; Johnson, J.; Kacal; Keough; King, K.; King, P.; King, T.; Klick; Koop; Krause; Kuempel; Lambert; Landgraf; Lang; Larson; Laubenberg; Leach; Longoria; Lozano; Lucio; Martinez; Metcalf; Meyer; Miller; Minjarez; Moody; Morrison; MunÄoz; Murphy; Murr; Neave; NevaÂrez; Oliveira; Oliverson; Ortega; Paddie; Parker; Paul; Perez; Phelan; Phillips; Pickett; Price; Raney; Raymond; Reynolds; Rinaldi; Roberts; Rodriguez, E.; Rodriguez, J.; Romero; Rose; Sanford; Schaefer; Schofield; Schubert; Shaheen; Sheffield; Shine; Simmons; Springer; Stephenson; Stickland; Stucky; Swanson; Thierry; Thompson, E.; Tinderholt; Turner; Uresti; VanDeaver; Villalba; Vo; Walle; White; Wilson; Workman; Wray; Wu; Zedler; Zerwas. Absent, Excused Ð Gervin-Hawkins; Smithee; Thompson, S. Absent Ð Deshotel; Dukes; Farrar. The speaker recognized Representative Bailes who introduced Dalton Currie, associate pastor of evangelism and outreach, First Baptist Church, Coldspring, who offered the invocation as follows: Our dear heavenly Father, as we come to you today, we ask a hedge of protection around our state leaders. -

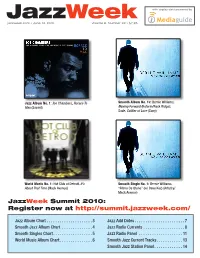

Jazzweek with Airplay Data Powered by Jazzweek.Com • June 14, 2010 Volume 6, Number 29 • $7.95

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • June 14, 2010 Volume 6, Number 29 • $7.95 Jazz Album No. 1: Joe Chambers, Horace To Smooth Album No. 1s: Bernie Williams, Max (Savant) Moving Forward (Reform/Rock Ridge); Sade, Soldier of Love (Sony) World Music No. 1: Hot Club of Detroit, It’s Smooth Single No. 1: Bernie Williams, About That Time (Mack Avenue) “Ritmo De Otono” (w/ Dave Koz) (Artistry/ Mack Avenue) JazzWeek Summit 2010: Register now at http://summit.jazzweek.com/ Jazz Album Chart .................... 3 Jazz Add Dates ...................... 7 Smooth Jazz Album Chart ............. 4 Jazz Radio Currents .................. 8 Smooth Singles Chart ................. 5 Jazz Radio Panel ................... 11 World Music Album Chart.............. 6 Smooth Jazz Current Tracks........... 13 Smooth Jazz Station Panel............ 14 Jazz Birthdays June 14 June 25 July 7 Lucky Thompson (1924) Joe Chambers (1942) Tiny Grimes (1916) June 15 June 26 Doc Severinsen (1927) Erroll Garner (1921) Dave Grusin (1934) Hank Mobley (1930) Jaki Byard (1922) Reggie Workman (1937) Joe Zawinul (1932) Tony Oxley (1938) Joey Baron (1955) July 8 June 16 June 27 Louis Jordan (1908) Joe Thomas (1933) Elmo Hope (1923) Billy Eckstine (1914) Albert Dailey (1938) June 28 July 9 Tom Harrell (1946) Jimmy Mundy (1907) Frank Wright (1935) Javon Jackson (1965) June 29 July 10 June 17 Julian Priester (1935) Noble Sissle (1899) Tony Scott (1921) Ivie Anderson (1905) June 30 Joe Thomas (1933) Cootie Williams (1911) Lena Horne (1917) Chuck Rainey (1940) Milt Buckner -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. MARIAN McPARTLAND NEA Jazz Master (2000) Interviewee: Marian McPartland (March 20, 1918 – August 20, 2013) Interviewer: James Williams (March 8, 1951- July 20, 2004) Date: January 3–4, 1997, and May 26, 1998 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 178 pp. WILLIAMS: Today is January 3rd, nineteen hundred and ninety-seven, and we’re in the home of Marian McPartland in Port Washington, New York. This is an interview for the Smithsonian Institute Jazz Oral History Program. My name is James Williams, and Matt Watson is our sound engineer. All right, Marian, thank you very much for participating in this project, and for the record . McPARTLAND: Delighted. WILLIAMS: Great. And, for the record, would you please state your given name, date of birth, and your place of birth. McPARTLAND: Oh, God!, you have to have that. That’s terrible. WILLIAMS: [laughs] McPARTLAND: Margaret Marian McPartland. March 20th, 1918. There. Just don’t spread it around. Oh, and place of birth. Slough, Buckinghamshire, England. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 WILLIAMS: OK, so I’d like to, as we get some of your information for early childhood and family history, I’d like to have for the record as well the name of your parents and siblings and name, the number of siblings for that matter, and your location within the family chronologically. Let’s start with the names of your parents. -

Still Drinking

Vol. 8 april2016 — issue 4 INSIDE: slow future - still drinking - line out: LUCA - priced outta b/cs - YOU’RE NOT PUNK & I’M TELLING EVERYONE - trauma Tuesday still poetry - Ask creepy horse - pedal pushing - QUITTING COFFEE - RICKSHAW HEART - record reviews concert calendar Priced outta b/cs I moved to College Station ten years ago. My family was somewhat unceremoni- ously kicked out of Seattle and needed somewhere to go. My wife found a job at Texas A&M so we loaded up the U-Haul and drove it 2000 979Represent is a local magazine miles in the July sun. We weren’t chased out of the for the discerning dirtbag. Emerald City because of crime or anything improper, we were chased out by the drastic increase in the cost of living and the continued stagnation of mid- Editorial bored dle class wages. We conducted a national search Kelly Minnis - Kevin Still for college towns with excellent schools to work at and communities attached that were inexpensive, low crime, and with excellent school systems. We got lucky when we landed in College Station. There Art Splendidness have been many times in recent years that we have Katie Killer - Wonko The Sane tried to move away but ultimately it did not come to fruition, most of the time because we’d say to our- Folks That Did the Other Shit For Us selves, “OK, where can we find a place in this new timOTHY danger - Mike e. downey - Jorge goyco - todd town that’s like here but not, you know, here?” and Hansen - chris Kirkpatrick - Jessica little - Amanda we could not find a satisfactory answer. -

Hree Sons, But

By:AARaymond H.R.ANo.A564 RESOLUTION 1 WHEREAS, Pianist Bobbie Nelson has been playing music for 2 virtually her entire life, and today, after nearly eight decades as 3 a performer, she is continuing to enrich the proud musical legacy of 4 Texas; and 5 WHEREAS, Bobbie Nelson was born on New Year 's Day 1931 in 6 Abbott; her parents divorced early in her childhood, and she and her 7 younger brother, Willie, were raised by their grandparents, William 8 and Nancy Nelson, who instilled in both children a deep love of 9 music; at the age of five, she learned to play keyboards from her 10 grandmother, first on the family pump organ and later on a piano her 11 grandfather bought for $35; after her brother learned the guitar, 12 the siblings began performing gospel songs together at school 13 events and at the local Methodist church; and 14 WHEREAS, In her early teens, Ms.ANelson got her start as a 15 touring musician, playing piano on the revival circuit with a 16 traveling preacher; at 16, she married Bud Fletcher, who organized 17 and managed the Nelson siblings ' first band, Bud Fletcher and the 18 Texans; she and her husband became the parents of three sons, but 19 after their marriage ended, she lost custody of her children for a 20 time because the courts disapproved of her occupation of playing 21 music in honky-tonks; her career was put on hold as she fought to 22 reunite her family, though she was able to put her talents to use 23 after being hired as a demonstrator for the Hammond Organ Company; 24 following stints in Fort Worth and -

Luqman Hamza Luqman Hamza Died in Late April

JUNE + JULY 2018 Mutual Musicians Foundation: History Looking Forward... and Broadcasting Brandon Draper: Never a Single Drum Set Jam’s Wonder Woman Retires TheTheB L U ROOM Mutual Musicians Foundation Saturday Jazz Ambassadors Magazine and July 28, 2018 Jackson County Historical Society 6:00-10:00 p.m. present Bennie, Basie & Bird PHOTO BY HEINRICH KLAFFS Mutual Musicians Foundation 1823 Highland Avenue, Kansas City, MO 64108 Tickets $35 Join us for food, drinks and jazz; an exploration into the sounds and styling from Bennie Moten, Count Basie and Charlie "Bird" Parker. Enjoy live performances with original and contemporary arrangements of their classics. For more information, visit www.mutualmusicianslive.com proceeds benefit PRESIDENT'S CORNER STEPHEN MATLOCK Jam Online...and We Don’t Mean a PDF Jam is about to be showcased its own website. At long last, get together with our members and anyone else who would like you’ll be able to read the magazine not just in print or in an to join us. This time we’re at Hush Speakeasy at 1000 Broadway awkward PDF, but with links to each article on its own web at 5:30 p.m. We start with a quick update meeting followed by page which will automatically adapt to the size of the screen jazz, dining and drinks. Music by Eclipse Trio starts at 6:30. on which you’re viewing it. Our articles, photos and ads – all We’d love to see you there. about Kansas City jazz – are going to be searchable all over the We’d also love to see you at 2018’s Supper Club, an eve- world.