Department of Economics Working Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marukawa University of Tokyo! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "#$%&'(!)*)+$! ,#!'#-!.&$./0*-+! '#-!1#$!.&-*-&#'!"&-2#/-!*/-2#$34!)+$5&44&#'!

University of California Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation Conference on Chinese Approaches to National Innovation University of California, San Diego La Jolla, California, June 28 - 29, 2010 Chinese Innovations in Mobile Telecommunications: Third Generation vs. “Guerrilla Handsets” Tomoo Marukawa University of Tokyo! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "#$%&'(!)*)+$! ,#!'#-!.&$./0*-+! '#-!1#$!.&-*-&#'!"&-2#/-!*/-2#$34!)+$5&44&#'! Chinese Innovations in Mobile Telecommunications: Third Generation vs. ‘Guerrilla Handsets” Paper presented at the IGCC Conference: Chinese Approaches to National Innovation La Jolla, California, June 28-29, 2010 Abstract: This paper analyses two cases of innovation which have taken place recently in China. Although both cases are related to mobile telecommunications, they represent very different types of innovation: One is a government-led, top-down type, which has been much publicized by the Chinese media as a successful case of China’s “indigenous innovation,” while the other is a bottom-up, unofficial one, which is usually not considered as an “innovation” in the Chinese media but rather as a case of industrial piracy. In this paper, however, I will shed light on the innovative aspect of the latter, and compare its market results with the former. JEL classification codes: L63, L86, O32 Tomoo Marukawa Institute of Social Science University of Tokyo Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, 113-0033, Japan e-mail: [email protected] Introduction This study analyses two cases of innovation which have taken place recently in China. Although both cases are related to mobile telecommunications, they represent very different types of innovation: One is a government-led, top-down type, which has been much publicized by the Chinese media as a successful case of China’s “indigenous innovation,” while the other is a bottom-up, unofficial one, which is usually not considered as an “innovation” in the Chinese media but rather as a case of industrial piracy. -

Mobile Phones in Society

Mobile phone From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "Cell Phone" redirects here. For the film, see Cell Phone (film). "Handphone" redirects here. For the film, see Handphone (film). Motorola L7 mobile phone A mobile phone, cell phone or hand phone is an electronic device used to make mobile telephone calls across a wide geographic area, served by many public cells, allowing the user to be mobile. By contrast, a cordless telephone is used only within the range of a single, private base station, for example within a home or an office. A mobile phone can make and receive telephone calls to and from the public telephone network which includes other mobiles and fixed-line phones across the world. It does this by connecting to a cellular network provided by a mobile network operator. In addition to telephony, modern mobile phones also support a wide variety of other services such as text messaging, MMS, email, Internet access, short-range wireless communications (infrared, Bluetooth), business applications, gaming and photography. Mobile phones that offer these more general computing capabilities are referred to as smartphones. The first hand-held mobile phone was demonstrated by Dr Martin Cooper of Motorola in 1973, using a handset weighing 2 kg.[1] In 1983, the DynaTAC 8000x was the first to be commercially available. In the twenty years from 1990 to 2010, worldwide mobile phone subscriptions grew from 12.4 million to over 4.6 billion, penetrating the developing economies and reaching the bottom of the economic pyramid.[2][3] Contents [hide] -

Oxygen Forensic Suite

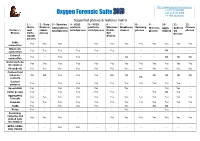

http://www.oxygen-forensic.com +1 877 9 OXYGEN Oxygen Forensic Suite +44 20 8133 8450 +7 495 222 9278 Supported phones & features matrix 1 – 2 - Sony 3 – Symbian 4 - UIQ2 5 – UIQ3 6 - 7 - 8- 9- 10- 11- 12- Nokia Ericsson S60 platform platform platform Windows Blackberry Samsung Motorola Apple Android Chinese Feature \ and classic smartphones smartphones smartphones Mobile devices phones phones devices OS phones Phones Vertu phones 5/6 devices classic devices phones Cable Yes Yes Yes - Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes connection Bluetooth Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes - - - NA - - connection Infrared Yes - Yes Yes - - NA - - NA NA NA connection General phone Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes information Phonebook Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Custom field labels for NA NA Yes Yes Yes NA NA NA NA NA NA contacts NA Contact Yes - Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes - pictures Speed dials Yes - Yes Yes Yes - Yes - - Yes Yes - Caller groups Yes - Yes Yes Yes Yes - - Yes NA Yes - Aggregated Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Contacts Calendar Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Tasks Yes - Yes Yes Yes - Yes - NA NA - - Notes Yes - - - - - Yes - - Yes - - Incoming, outgoing and Yes Yes Yes - - Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes missed calls information GPRS, EDGE, - - Yes Yes - - - - - - - CSD, HSCSD - and Wi-Fi traffic and sessions log Sent and received SMS, - Sent SMS - Yes Yes Yes(2) - - - - - - MMS, E-mail messages log Deleted - messages - - Yes(1) - Yes(1) - - - Yes(8) - - information Flash SMS -

Qiao Xing Mobile Communication (NASDAQ: QXM) Memo Date: 04/26/2011 Analyst: Alexander Abosi Company: Qiao Xing Moblie Communications

Qiao Xing Mobile Communication (NASDAQ: QXM) Memo Date: 04/26/2011 Analyst: Alexander Abosi Company: Qiao Xing Moblie Communications Date Price 52w range Market Cap Ending Dec 31 (in $ ‘000,000) 2007 2008 2009 2010* 04/26/2011 $2.88 $2.10-$5.56 152.68M Revenue 31,410 21,548 16,329 TBA (05/02) Growth (31.4%) (24.2%) TEV -161M EBITDA 7,613 6,467 317 TBA (05/02) Debt/Equity 25.6 Growth (15.1%) (95.1%) P/E N/A Net Income (loss) 5,648 4,238 (2,503) (TBA 05/02) Growth (25%) (159.1%) Short 0.3% EPS 11.69 7.44 (7.07) (TBA 05/02) Interest (% of Float) *2010 will be released 05/02/11. A 2010 column is included because QXM fiscal year ended Dec 31 2010. Company Description QXM is a domestic manufacturer of mobile handsets and cell phones in The People’s Republic of China. The company manufactures cell phones based on the Global System for Mobile communications (GSM) and it markets its products primarily in China, although it has an international presence as well. The company’s products have been primarily marketed under the CECT brand name. QXM’s in-house research and development team is in charge of manufacturing the actual handsets, the mobile phone application software, as well as product interfaces. The company currently employs approximately 600 people. Qiao Xing Mobile communications spun off from its parent company Qiao Xing Universal Resources Inc. in 2007 as a standalone mobile phone manufacturer. Investment Thesis I believe QXM is a rare gem, in that it is a window into the Chinese mobile phone market from here in the USA- due to the fact that it is the only Chinese mobile phone company listed on either the NYSE or the NASDAQ. -

Artwizz Powerplug/ Carplug Compatibility

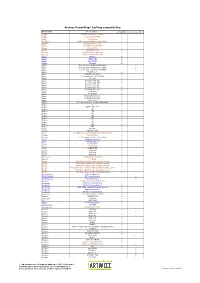

Artwizz PowerPlug/ CarPlug compatibility: Manufacturer: Product-Name: compatible: not compatible: ACER PNA P610 navigation system x ACER Pocket PC N311 PDA x ACME FlyCam One x AC Ryan AluBox (external Multimedia Hard Drive) x ADAPT AD-350+ GPS receiver x Aiptek Mini Beamer Cinema U10 x Aiptek PenCam Trio x Aiptek VideoSharier VS1 x Anycom BTM-100 bluetooth mouse x Anycom HCC-250 Bluetooth Car Kit x Apple iPhone x Apple iPhone 3G x Apple iPhone 3GS x Apple iPhone 4 x Apple iPod 1st. gen. (charged via FireWire) x Apple iPod 2nd. gen. (charged via FireWire) x Apple iPod 3rd. gen. (charged via FireWire) x Apple iPod 4th. gen. x Apple iPod 5th. gen. (video) x Apple iPod classic 80, 120 & 160 GB x Apple iPod mini x Apple iPod nano 1st. gen. x Apple iPod nano 2nd. gen. x Apple iPod nano 3rd. gen. x Apple iPod nano 4th. gen. x Apple iPod nano 5th. gen. x Apple iPod Photo x Apple iPod shuffle x Apple iPod shuffle 2nd. gen. x Apple iPod shuffle 3rd. gen. x Apple iPod touch x Apple iPod touch 2nd. gen. and fall edition 2009 x Archos 2 x Archos (Gemini) XS 202s x Archos 60 x Archos 104 x Archos 105 x Archos 204 x Archos 404 x Archos 5 x Archos 504 x Archos 604 x Archos 605 x Archos 605 WiFi x Archos Gmini XS 100 x Artwizz "CoolBlue" Cooling Stand with fan for Nintendo Wii x Artwizz FanLight USB x Artwizz PS3 Charging Stand for 2 Controllers x ASUS m530w Smartphone x ASUS P535 Smartphone x ASUS myPal A636N x ASUS myPal A639 x auvisio myBEAT IBD x auvisio SoftTouch x Axxion AMP-210 x Axxion AMP-220 x B-Speech TX2 Bluetooth Transmitter x BeBook E-Reader -

The Implication of Open Innovation and Open Source to Mobile Device Manufacturers

The Implication of Open Innovation and Open Source to Mobile Device Manufacturers By Yuanwen Wayne Liu M.S. Computer Science (Purdue University 2000) M.S. Biochemistry (Indiana University 1998) Submitted to the System Design and Management Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science in Engineering and Management At the ARCHIVES Massachusetts Institute of Technology MASSACHUSETTS INSTRtTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2009 SEP 2 3 2009 C 2009 Yuanwen Wayne Liu All rights reserved LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created Signature of Author Y Yuanwen Wayne Liu "A tl System Design and Management Program June 2009 Certified by Michael A. M. Davies (~ni~ I r, MIT Sloan School of Management Certified by k../ Patrick Hale Director, System Design and Management Program The Implication of Open Innovation and Open Source to Mobile Device Manufacturers By Yuanwen Wayne Liu Submitted to the System Design and Management Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science in Engineering and Management Abstract Innovations largely contribute to a technology company's continuous survival and its competitiveness in the market place. Traditionally most companies employed closed innovation model. They kept their discoveries or inventions highly secret and made no attempt to assimilate information from outside. This model worked well until 1990s when advances in technology and society had facilitated information diffusion dramatically. Mobile industry, as one of the most rapidly changing industries, is also forced to adopt the open innovation model in various forms. -

Shanzhai Products in Everyday Life: Ethnographic Fieldwork in China Master of Arts Thesis

ETHNOGRAPHIC fiELDWORK IN CHINA WU YIYIN G -·2010- 2011·- Shanzhai Products in Everyday Life: Ethnographic fieldwork in China Master of Arts Thesis WU Yiying Supervisor: Turkka Keinonen Industrial and Strategic Design Aalto University School of Art and Design 2011 To maintain the anonymity of all my respondents and informants, only family names are given. The use of the pictures of my five respondents is by their permission. -thalll:s "to : TURKKA I<EI NONEN SALIL SAYED JQck whalen Yang )(iong Juk\t(ll Torronen Po.. Jun H.M.J.J. Snelders Wang Jio Ilpo kos kinen Wan, Yin yin Yang Wenq·,n Li :Tie chen Yineo Yo"g J i don3 Lawyer Sao M. To.niguehi 2n ... Lin Xue Hoio.n Zho."9 S hen wei wang Yuchen zhoi WenSi Ren Tong Wu Yiwen Wo"g Lei chen Wenxin Jiollg Zho.owei Sons chongDt! i Hu x iC>09uon3 Mu Sino.n Zhang L;nSYCtn D;1I9 Hu;!;an Tin Zni nOIl.3 CONTENTS 1 INTODUCnON 3 research question 4 background 5 literature review 7 position of the researcher 11 2 METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK 13 ethnography 15 ethmethodology 16 methods and analysis 16 thick description 18 shanzhai users and products in my model 19 3 DOING FIELDWORK 21 entering fields 25 taking field notes 26 stakeholder interviews 26 in-depth interviews with shanzhai users 27 hanging out 28 4 NON-AUTHENTIC PRODUCT CATEGORIES 33 aim 35 non-authentic product categories 38 A-replicas of luxury brands 40 shanzhai mobile phones + shanzhai puma logos 42 5 SHANZHAIUSERS 45 JIANG Thick Description: hanging out with Jiang 51 being of Jiang 59 expressive objects: cheap and beautiful 61 new meaning -

Shanzhai Mobile Phones

Current Chinese Consumer Purchase Behaviour Case: Shanzhai Mobile Phones Jun Li Bachelor’s Thesis Degree Programme in International Business 2010 Abstract January 2010 Degree programme in International Business Author Group Jun Li POBBA Title of Thesis: Number of pages and appendices Current Chinese Consumer Purchase Behaviour Case: Shanzhai Mobile Phones 79+8 Supervisors Evariste Habiyakare and Sirpa Lassila This study demonstrates the factors which influence consumer behaviour in general, and the role that the brand plays in the consumer buying process. The target of this thesis is the Chinese mobile phone market. The objective is to outline the current Chinese consumer behaviour when the Shanzhai mobile phone is launched. In addition, it focuses on what Chinese consumers think about Shanzhai. Also the dynamics of Shanzhai brought on the market are discussed. The theoretical approach for the study is based on concepts of consumer behavior, the consumer buying process and the brand image facet. In order to collect empirical data, a quantitative research technique was used. An online survey was carried out and sent out by Internet. The questionnaire was designed in accordance with the theoretical framework. Secondary data was gathered for analyzing social and cultural influences, the Shanzhai phenomenon. Primary data was used to illustrate current Chinese consumer behaviour when it comes to purchasing mobile phones. A total of 152 responses were obtained. The result shows that Chinese consumer behaviour is strongly influenced by its social and cultural environment; different gender causes different behaviour; the outer appearance of the mobile phone seems to be the chief factor which affects consumers’ buying decision.